The Two-Parent Privilege – Part 7

When increased government benefits pull more men out of the labor market, marriage rates decline.

Continuing this essay series on the benefits to children of two-parent families, this essay will explore how, as government benefit programs have expanded and become more attractive as an alternative to work, men who drop out of the workforce have become less attractive to women as marriage partners.

As economist Melissa Kearney writes in her book The Two-Parent Privilege: How Americans Stopped Getting Married and Started Falling Behind:

Insofar as the reduction in marriage and the rise in nonmarital childbearing reflects an erosion of men’s (and father’s) economic standing, then dads in more recent decades would bring lower resources into the home than they would have in previous decades … [T]his does seem to be at least part of the problem—to put it in stark (coldhearted) terms: the economic attractiveness of non-college-educated men has been diminished. This diminishment is part of the underlying problem. It means that even if there were a magic wand that one could wave to increase rates of marriage, class gaps in household resources would remain.

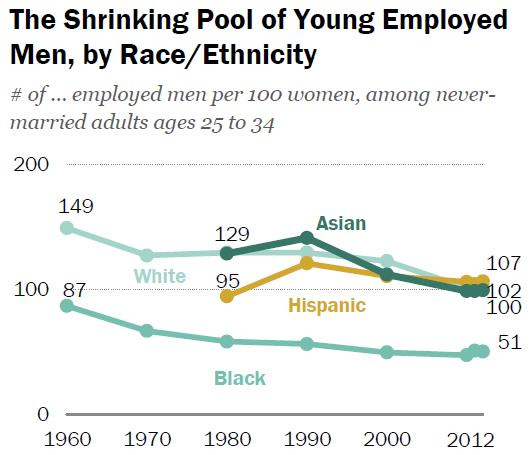

There is a rising number of never-married adults as the number of employed men per 100 women has shrunk.

The drop in the number of employed men per 100 women has particularly affected the black community.

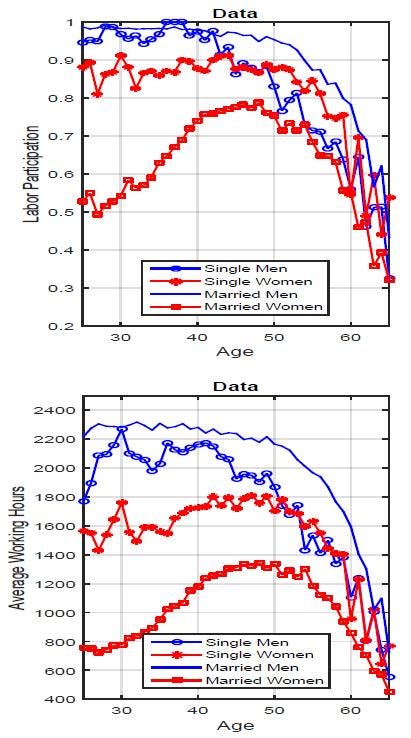

In contrast to a system of increased government welfare benefits that disincentivizes men to work, which leads to fewer marriages by making more men less attractive marriage partners, marriage itself does the opposite: marriage incentivizes work by men. Researchers have found that entering marriage generates an almost 20 percent increase in earnings for men, with about one-third to one-half of the marriage earnings premium due to higher work effort. Their conclusion: “[our] findings reveal statistically significant, causal impacts running from marriage to wage rates and working hours, from working hours to subsequent wages, and from both wage rates and working hours to marital status. Putting the wage and hours effects together, we estimate earnings gains of 21 percent caused by entering or remaining married as compared to staying single.” (Interestingly, and related to the subject of bias among university faculty, academic economists generally ignore the beneficial economic effects of the “social issue” of marriage, even when marriage has the very same “wage premium” effect as the “non-social issue” subjects they tend to prefer to discuss, such as college attendance.)

Without the responsibility of families to provide for, unmarried American men have tended to work fewer hours and make less money.

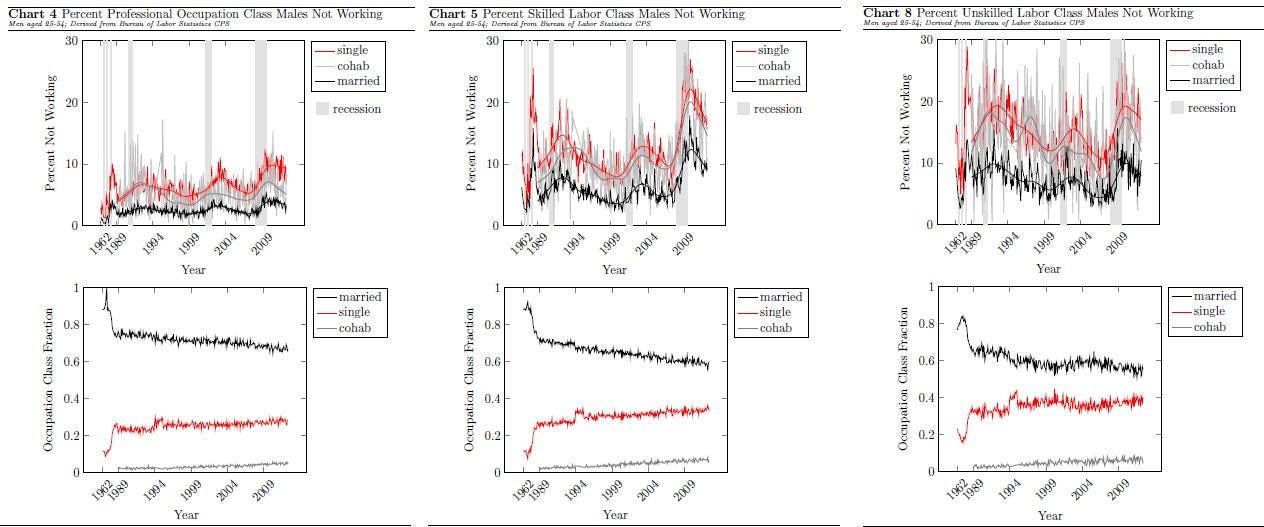

Unmarried American men have also tended to drop out of the labor force entirely. Marriage is associated with more working among professional, skilled, and unskilled occupations alike.

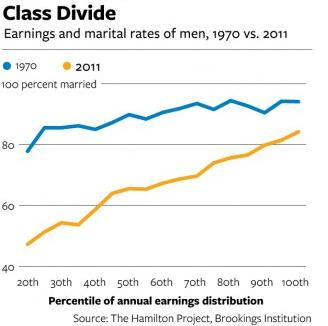

The figure below shows both the change in earnings and the change in the share of married men by earnings percentile from the years 1970 to 2011. The figure illustrates a strong correlation between changes in earnings and changes in marriage: men in lower income ranges that experienced the largest declines in marriage also suffered the most economically.

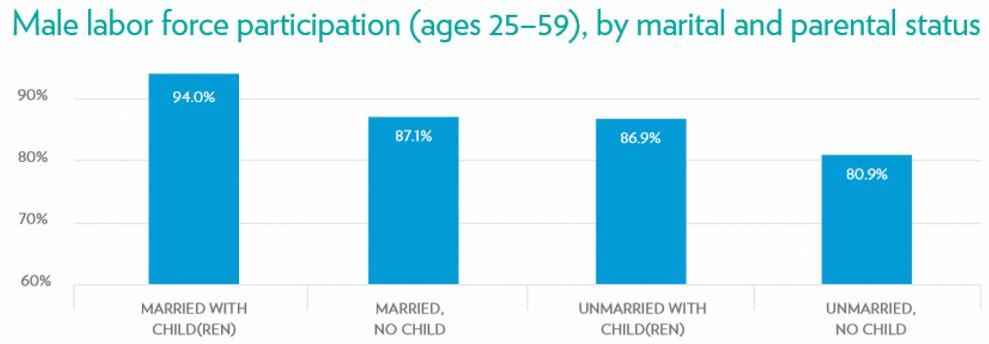

Married men with children have significantly larger labor force participation rates than unmarried men with no children.

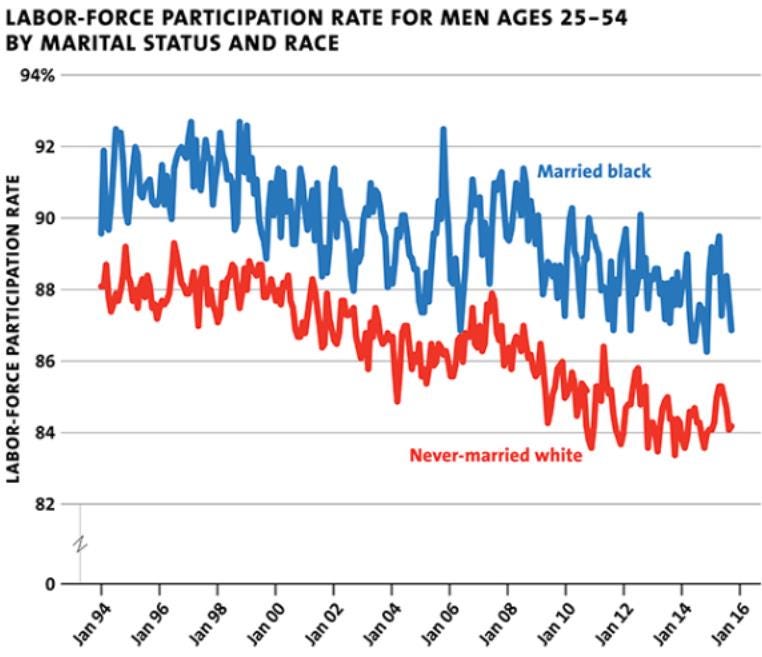

Labor participation rates of prime-age married black men are higher than those of never-married white men of those same ages.

Married people earn over 88 percent of total earnings and contribute over 86 percent of the hours worked during the life cycle of those ages 25 to 65.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll explore whether or not American society has crossed a Rubicon of sorts, as returning to a social ethic of marriage becomes increasingly more difficult.