The Two-Parent Privilege – Part 3

Exploring the many beneficial outcomes for children of two-parent families.

Continuing this essay series on the benefits to children of two-parent families, this essay will explore the many beneficial outcomes for children of two-parent families. As economist Melissa Kearney writes in her book The Two-Parent Privilege: How Americans Stopped Getting Married and Started Falling Behind, those benefits include greater college completion rates:

Going back to longitudinal studies that look at family structure more generally, a 2022 study in a macroeconomics journal documents — again using data from the PSID [Panel Study of Income Dynamics] — that family structure has become even more important over time in shaping a child’s educational attainment. The study shows that whether a child lives with one or two parents is an important predictor of college completion, even after statistically controlling for a host of other individual and family factors, including family income. The study further shows that the predictive power (in a statistical sense) of having two versus one parent in the home is stronger for individuals who turned 28 between 2006 and 2015, as compared to individuals who turned 28 between 1995 and 2005, holding other variables constant. The documented importance of early-childhood environments in determining college completion rates are so large that policy simulations the researchers ran implied that subsidizing pre-college investment for one-parent families has a larger impact on college completion and lifetime earnings than alternative interventions like tuition subsidies or cash transfers.

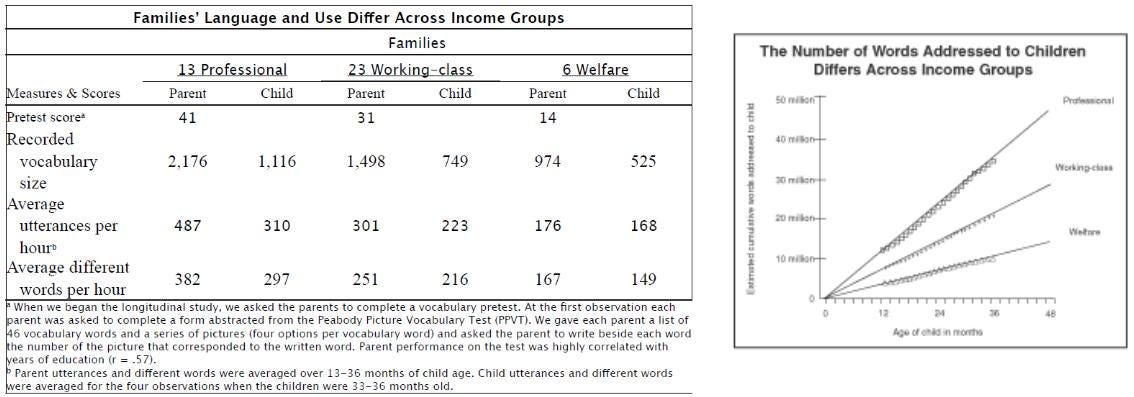

Vocabulary is essential to complex thinking, and data show that children’s vocabularies are based on the number of words to which they are exposed in the home. Fewer parents mean children will be exposed to fewer words, and consequently have lower vocabularies, which will affect their prospects through life.

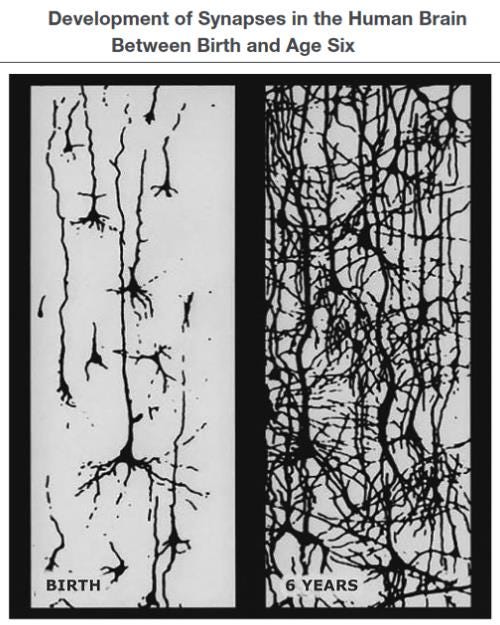

During the first five years, hundreds of neural connections are formed in a young child’s brain every second, “wiring” its structure, driven almost entirely by ongoing interactions with adults. From birth, back-and-forth, language-rich communication in the context of secure, loving relationships with adult caregivers literally builds the architecture of children’s brains.

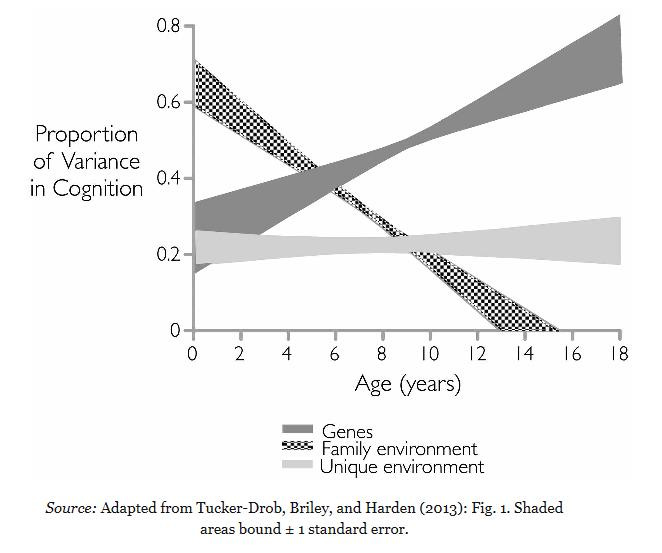

A child’s environment has a large effect on the child’s cognitive ability early in life, but that effect reduces in strength as time goes on. As Charles Murray has written in Human Diversity:

The shared environment plays a large role in determining IQ during the first few years of life, diminishing thereafter. By the time people reach adolescence, almost all studies have found that the shared environment has a negligible relationship to IQ. Both findings are best documented in a review of the literature by Elliot Tucker-Drob and his colleagues at the University of Texas. The graph below summarizes their results. Source: Adapted from Tucker-Drob, Briley, and Harden (2013): Fig. 1. Shaded areas bound ± 1 standard error. The graph combines the results of publications reporting on 11 different longitudinal twin and adoptions studies. In infancy and the first few years of life, the shared environment explains a large proportion of the variance in scores—around two-thirds. By seven years of age, that figure has dropped to about one-third. By 14, it is zero. [‘Unique environment’ refers to things one twin is exposed to, but not the other.]

Two-parent families, through increased parental monitoring, also inculcate more self-control (and personal responsibility) in their children generally. As Roy Baumeister and John Tierney write in their book Willpower: Rediscovering the Greatest Human Strength:

In an attempt to prevent juvenile delinquency during the early 1940s, counselors visited more than 250 boys in their homes twice a month. They recorded observations about the family, the home, and the life of the boys. On average, the boys were about ten when the study began, and about sixteen when it ended. Decades later, when the boys had grown up and were in their forties and fifties, the notes were studied by a researcher named Joan McCord, who compared the teenage experiences with subsequent adult behavior—in particular, criminal behavior. A lack of adult supervision during the teenage years turned out to be one of the strongest predictors of criminal behavior. The counselors had recorded whether the boys’ activities outside of school were usually, sometimes, or rarely regulated by an adult. The more time the teenagers spent under adult supervision, the less likely they were to be later convicted of either personal or property crimes. The passage of decades has not erased the value of parental monitoring. A recent compilation of studies on marijuana use, totaling more than thirty-five thousand participants, showed a robust link to parental supervision. When parents keep tabs on where their children are, what they do, and whom they associate with, the children are much less likely to use illegal drugs than when parents keep fewer close tabs. Similarly, recent studies of diabetic children have found multiple benefits of parental supervision. Adolescents have higher self-control to the extent that their parents generally know where their offspring are after school and at night, what they do with their free time, who their friends are, and how they spend money. Although type I diabetes comes on early in life and may be mainly a result of genes, the adolescents with high trait self-control and high parental supervision have lower blood sugar levels (thus, less severe diabetic problems) than others. In fact, having a mother or father who keeps track of the child’s activities, friends, and spending habits can even compensate to some degree for lower levels of self-control, in terms of reducing the severity of diabetes. The more that children are being monitored, the more opportunities they have to build their self-control. Parents can guide them through the kind of willpower-strengthening exercises we’ve discussed earlier, like taking care to sit up straight, to always speak grammatically, to avoid starting sentences with “I,” and to never say “yeah” for “yes.” Anything that forces children to exercise their self-control muscle can be helpful: taking music lessons, memorizing poems, saying prayers, minding their table manners, avoiding the use of profanity, writing thank-you notes.

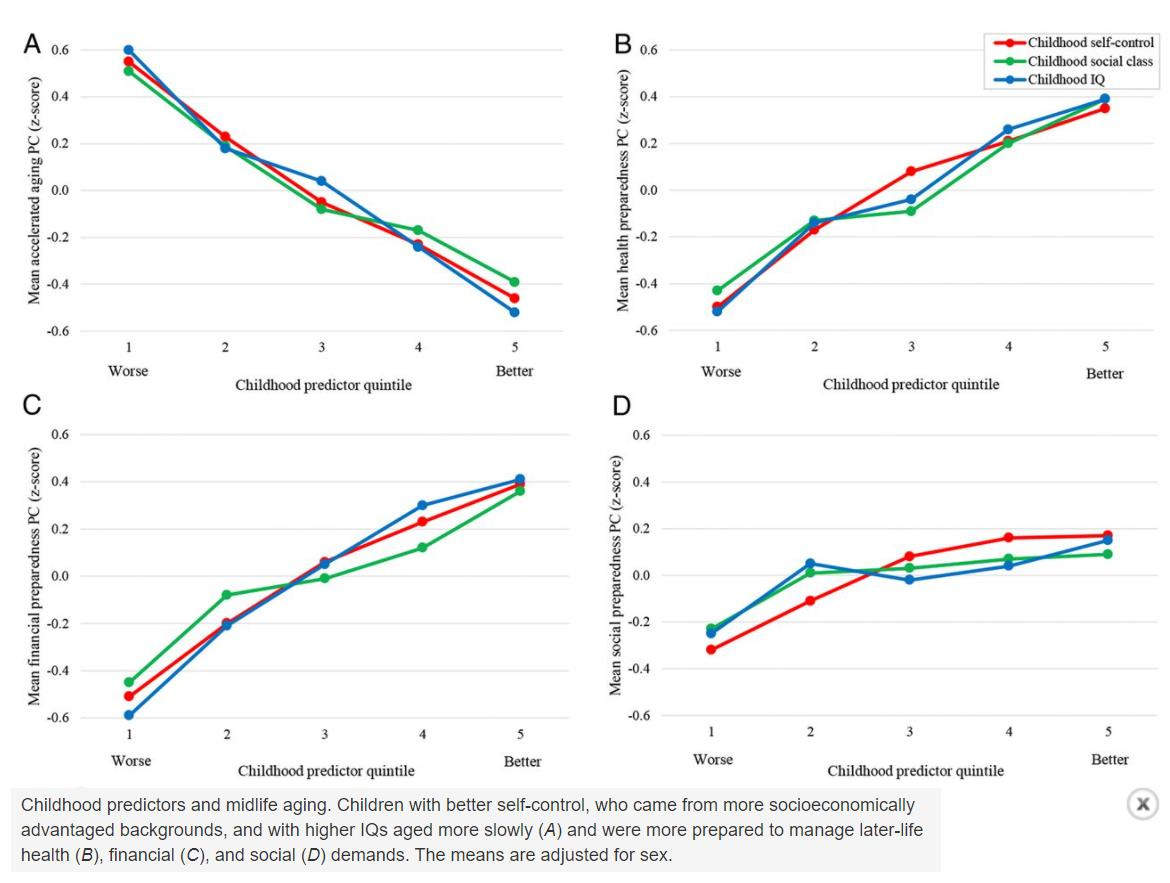

Researchers have also reported the long-term benefits of childhood self-control as follows: “We followed a population-representative cohort of children from birth to their mid-forties. As adults, children with better self-control aged more slowly in their bodies; showed fewer signs of brain aging; and were more equipped to manage later-life health, financial, and social demands. The effects of children’s self-control were separable from their socioeconomic origins and intelligence.”

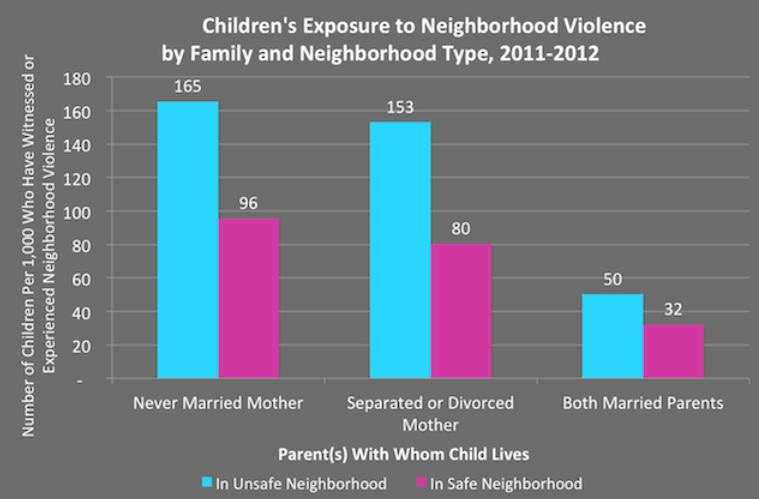

According to the 2011-2012 National Survey of Children’s Health, conducted by the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics, children raised by both married parents in both unsafe and safe neighborhoods are exposed to significantly fewer episodes of neighborhood violence than children raised by never-married mothers, or separated or divorced mothers.

There is also evidence of other great advantages to children when they live with both their biological parents. As Kearney writes:

[T]here is some social science evidence suggesting that children tend to have better outcomes when they live with two biological parents. For example, there is a study using large-scale, nationally representative data showing that stepmothers generally do not invest as much in their stepchildren’s health as do biological mothers, even after adjusting for household income and other relevant characteristics. Another large-scale study finds that adolescents who experienced their mother marrying a stepfather after parental divorce had worse behavioral outcomes and more negative feelings than adolescents whose biological parents remained continuously married. That situation additionally brings up issues of transitions and instability, which are generally understood to be difficult for children. In a 2005 article published in the Future of Children, sociologist Paul Amato concluded that studies consistently indicate that children in stepfamilies tend to exhibit social and behavioral problems on a similar scale to children in single-parent homes, and more so than children living with continuously married biological parents.

Research over the last several decades also shows that it is good for children when both men and women are involved in the raising of children, as both male and female parents tend to bring their own unique perspectives and experiences to children to help them cope later in life:

There are many similarities in the ways the mothers and fathers parent (Parke 2009). Yet, when a father invokes his heartfelt imperative to play an active role in the life of his child, he tends to do it in typically “father-like” ways. Observations of parent-child interaction that have been performed over the last three decades show persistent patterns of parenting styles that are specific to the sex of the parent. Mothers are more verbal and nurturing with their children (Bugen and Humenick 1983), while fathers are more action-oriented, demanding, and logical (MacDonald 1993), and more likely to prohibit certain activities in infants (Brachfield-Child 1986). As researchers observed parents playing with their infants, they found that moms often contain a baby’s movements by holding his or her legs or hips while calming the child down with a soft voice, slow speech, and repeated rhythmic phrases. Fathers, on the other hand, often poke their baby, pedal his or her legs, make loud or abrupt noises, and stimulate the infant to higher pitches of excitement (Moss 1974). Fathers are prone to tease their child, a distinctly non-motherly activity that researchers actually believe helps improve children’s ability to handle ambiguity as they grow older (Labrell 1994). A review of the literature demonstrates myriad gender-based stylistic differences; on average, compared to mothers, fathers spend a greater percentage of their time playing with children, and tend to engage in more unconventional and more physical play (Parke 2009). As author John Gottman (1997) describes, “Dads often make up idiosyncratic or unusual games, while moms are more likely to stick to the tried-and-true pursuits … The dads were more able … to take their children on an emotional roller coaster, going from activities that commanded minimal attention to those that got the babies quite excited. Mothers, in contrast, kept their play and their babies’ emotions on a more even keel” (170). Parenting styles correlate to biological differences between men and women. Women, compared to men, have higher levels of oxytocin—the hormone responsible for emotional bonding—and oxytocin receptors. Oxytocin serves to calm anxiety, reduce motor activity, and foster an increase in touching. A reciprocal relationship exists between oxytocin and touching—so that the presence of this hormone promotes touching, and the touching increases oxytocin levels (IsHak, Kahloon, and Fakhry 2011). In contrast, testosterone—present in men at levels tenfold higher than women—is correlated to an increase in motor activity in infant boys (Campbell and Eaton 1999) and mammals (Sanderson and Crews 2009), and may be responsible for higher levels of physical activities in men compared to women (Hermann, McDonald, and Bozak 1978). While biological factors may be at play in some of the differences between mother-play and father-play, there are multiple sociological positive effects of fathers in the household. Among the findings Dr. Gottman (1997) describes: “Five-month-old baby boys who have lots of contact with their fathers are more comfortable around strangers” (170). “One-year-old babies cried less when left alone with a stranger if they had more contact with their dads” (170). “Kids whose fathers showed high levels of physical play were more popular among their peers” (171). “While our studies showed that mother-child interactions were also important … compared to the father’s responses, the quality of the contact with the mother was not as strong a predictor of the child’s later success or failure with school and friends” (172). While Gottman readily points out the ways in which the father-child bond imbues the young child with strength and confidence, he also reviews data that shows the negative effects on the child of being raised without a father: “Research indicates … that boys with absent fathers have a harder time finding a balance between masculine assertiveness and self-restraint” (166). “Looking at academic achievements … boys with absent fathers did the worst, and the boys whose fathers were present and available did the best … high involvement by fathers seems to be linked to girls’ career and academic achievements as well” (178). Adolescent well-being also correlates to having a father inside the home. Drawing on data from the National Survey of Adolescent Health, Eggebeen (2012) has demonstrated that fathers make contributions that may exceed that of mothers’. For instance, the number of activities that a father participated in with a son was correlated with a reduction in depressive symptoms in the adolescent male. This finding did not correlate with the mother’s frequency of activities with her son. Moreover, while a parent’s strategies for dealing with conflict do not seem to affect their sons, a mother’s (but not a father’s) poor conflict management style predicts social and physical aggression in daughters (Underwood et al. 2008). Because the default responsibility of raising children lies with the mother, there are no studies that ask whether it is in the child’s best interest to be raised by women, only whether and if, it is good for men to be involved in the raising of children. It is clear that the answer to that question is a resounding “yes.”

From a cultural evolutionary perspective, it is understandable that males and females generally have come to have statistically different interests, and to be most amenable to learning about those interests from same-sex models. As explained by Joseph Henrich in his book “The Secret to Our Success: How Culture is Driving Human Evolution, Domesticating Our Species, and Making Us Smarter”:

[T]he key to understanding the division of labor [among different-gender parents] is to recognize that it’s rooted in a division of information. As cultural information begins to accumulate such that no one individual can know everything, pair-bonded couples can specialize in complementary bodies of culturally acquired skills, practices, and knowledge. Female hunter-gatherers, by virtue of birthing, lactating, and providing primary care for babies, need to focus on learning about infant handling, nursing, weaning, food preparation and processing, and any foraging skills that guarantee a steady flow of calories. Males, by contrast, can specialize in know-how about toolmaking, defense, weapons, hunting, and tracking … However, culture-gene coevolution may eventually have endowed males and females with different content biases, making them differentially more or less interested in learning about distinct topics. For example, girls might tend to be more interested in infants, whereas boys might tend to be more interested in projectiles. Supporting this possibility, male infants between six and nine months readily imitate the gentle propulsive actions on a balloon (by patting it around) by same-sex models more than female infants (who don’t seem equally fascinated by propulsive movements).

In the next essay in this series, we’ll explore the many beneficial outcomes for parents of two-parent families.