The Two-Parent Privilege – Part 2

Is more income for single parents the answer, or is there something else special about two-parent families?

Continuing this essay series on the benefits to children of two-parent families, this essay will explore whether more income for single parents might be the answer to otherwise relatively worse child outcomes, or whether there’s something else special about two-parent families that leads to better outcomes for children.

As economist Melissa Kearney writes in her book The Two-Parent Privilege: How Americans Stopped Getting Married and Started Falling Behind:

If loving our children were enough to ensure they would be okay, then all children would be okay … Data confirm that having access to more resources enables parents to invest more in their children. More highly resourced parents tend to spend more money and time investing in their children. Why? The evidence suggests that it’s not because more and less resourced parents have different views about what their children need or different preferences about what they want to do for or with their children. Rather, a highly resourced couple has way more resources to draw on when it comes to raising children. A lack of resources, meanwhile, makes it harder for low-income, single parents to do all they would like to do for their children. Some of this difficulty is about money (since one working adult tends to bring in less income than two working adults, especially if they have the same level of education), but some of it is about having another committed adult to split the workload with, to watch the kids while you’re working or doing something else, or to pick up the emotional load when you’re just too drained … Two-parent households are much more likely to have a higher level of household income and thus to be able to afford—or even spend lavishly—on children’s activities. Activities like being on a sports team or playing an instrument help children develop their talents, their mind, their passions, their focus and dedication—and simply experience joy. They give them meaningful things to do with their time, outside of school and off their phones and devices.

And so Kearney asks:

[H]ow does family structure matter—or does it even matter—for people with higher levels of resources? If an unpartnered mother is well-educated and highly resourced, do her kids tend to do just as well as the kids of her married peers? … Even when we statistically adjust for household income (in addition to the demographic factors), sizable differences in outcomes remain. Put another way, a child born in a two-parent household with a family income of $50,000 has, on average, better outcomes than a child born in a single-parent household earning the same income … There are a variety of mechanisms beyond income through which children might benefit from living in a married-parent home. For instance, parents in two-parent households might have more time and energy to devote to parenting. Furthermore, low levels of income and single parenthood are often associated with other stress factors that are directly harmful to children’s development, such as residential instability, maternal stress, and less positive parenting practices.

The result is that public policies that send more taxpayer money to single parents won’t be any sort of silver bullet solution. As Kearney writes:

[E]ven if policy makers were to dramatically scale up government support and shrink income gaps between one- and two-parent families, there would still be meaningful differences in children’s experiences and outcomes … [T]he concept of specialization in a marriage still applies to many couples, allowing individual spouses to focus their efforts on the tasks they are relatively better at, thus using their time more efficiently … The key insight is that any specialization that happens among married parents further increases the relative resources of a two-parent household compared to a one-parent household.

As Kearney explains:

If there are two parents in a family home, there are a bunch of things that will be different compared to a one-parent home. Having a second parent typically means a higher level of income, and all the associated advantages that higher income can buy for a family, such as a home in a safer neighborhood with better schools, healthier foods, enriching activities and trips, etc. A second parent also means another adult devoting time to the child, whether it be in the form of basic care (like feeding or dressing a young child), educational time (like reading to a child or helping them with their homework), travel time (like driving to sports practice or music lessons), or just time spent together in leisure and fun … Some social scientists have used longitudinal data, which follows research subjects for a long time, from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to trace children’s outcomes during childhood and into adulthood. The PSID is the longest-running longitudinal household survey in the world: It began in 1968 with a nationally representative sample of over 18,000 individuals living in 5,000 families in the United States. Directed by researchers at the University of Michigan, survey conductors have been collecting detailed information on this initial sample and their children since then, gathering data on employment, income, wealth, expenditures, health, marriage, childbearing, child development, education, and numerous other topics. A study published in 2014 using this data showed what is probably intuitive for most: that children who were raised in a household with a single mother grew up with a lower level of childhood household income over their childhood than children who grew with continuously married parents. This trend persisted even after the researchers statistically adjusted for the sex, race, and birth order of the child, the age of the mother at the time of her first birth, and the mother’s level of education. The childhood income deficits were also larger for children whose mothers were never married, as compared to those whose mothers married after the child’s birth or who were married at the time of birth but subsequently divorced … Looking at the children’s outcomes as they aged into adults, the same study showed that children of mothers who were never married have substantially lower income in adulthood than the children of continuously married parents (again after adjusting for demographic characteristics).

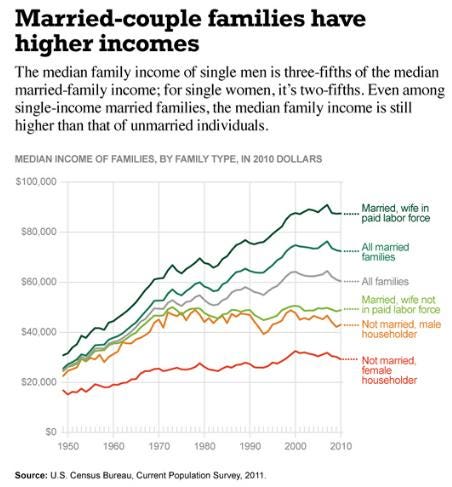

Married couples have higher incomes than unmarried people, as married couples benefit from economies of scale and the division of labor, and tend to save and invest more for the future.

Married couples are also much more likely to own a home, which builds family equity. As Tobias Peter writes:

In the American ethos, owning a home is viewed as a stepping-stone to the American Dream. However, due to rising house prices over the last several decades, this dream has become further out of reach for many Americans, particularly lower-income households. Yet a new analysis by the AEI Housing Center reveals that one group outperforms all others when it comes to achieving homeownership: married couples. Those who are married are able to punch disproportionally above their weight financially. The adage “two can live as cheaply as one” has a ring of truth. By pooling financial assets, married households are able to save more and bid more successfully on homes. By living together, married couples are able to benefit from economies of scale and, with two wage earners, have a higher combined income. When focusing exclusively on White households to eliminate any impact of race, households headed by a married White individual earned about twice as much income (144% of area median income (AMI)) as households headed by unmarried White individuals (71% of AMI) for years 2015-2019 per microdata from the American Community Survey (ACS). In a similar fashion, households headed by married Black individuals earned more than twice as much income (115% of AMI) as households headed by unmarried White individuals (49% of AMI) …

By sharing child-raising responsibilities, each parent in a two-parent family has more “emotional bandwidth” when dealing with children. As Kearney writes:

Emotional bandwidth is different from time. Having emotional bandwidth means not being so weighed down by stress that you can’t sit and read to your child, or help them with homework, or volunteer to drive them to an activity or event. Parents with fewer resources—money, time, emotional support from a committed spouse and co-parent—live with a higher level of daily stress, which likely impinges on their ability to do the kinds of activities they might otherwise want to do with their children.

Along with tending to be more centered when dealing with their children, parents in two-parent families can spend more time with their children. As Kearney writes:

Like the discernible difference in childcare time between more- and less-educated parents, there is a gap in childcare time by marital status. On average, married mothers spend more time per week engaged with their children than do unmarried mothers.10 Married mothers with at least one child under age 18 spend an average of 15.1 hours per week in dedicated childcare, meaning that their primary activity is related to the child—dressing them, reading to them, driving them to an activity, and the like. They also spend, on average, 45.4 hours with their child(ren), meaning that their child or at least one of their children is with them, even if their primary activity isn’t centered on the child. Unmarried mothers spend an average of 12.7 hours per week in dedicated childcare and 37.8 hours with their child or at least one of their children. The luxury of being able to spend less time working and more time engaged with one’s child can be thought of in just that way—as a luxury that married mothers, on average, more often have because there is another adult in the household … Research findings are consistent with the notion that the more time parents spend with their children, especially in developmentally appropriate activities, the better the child does academically and emotionally … There are many studies … that find a positive connection between the amount of time parents spend with their children and children’s subsequent academic and behavioral outcomes. Two are especially compelling from a research methodology perspective. A 2019 study looked at differences between siblings in the same households based on the amount of time they spent reading with their mothers and their subsequent reading test scores on standardized tests … [T]he researchers provided evidence that extra reading time with one’s mother leads to a sizable improvement in standardized reading test scores.

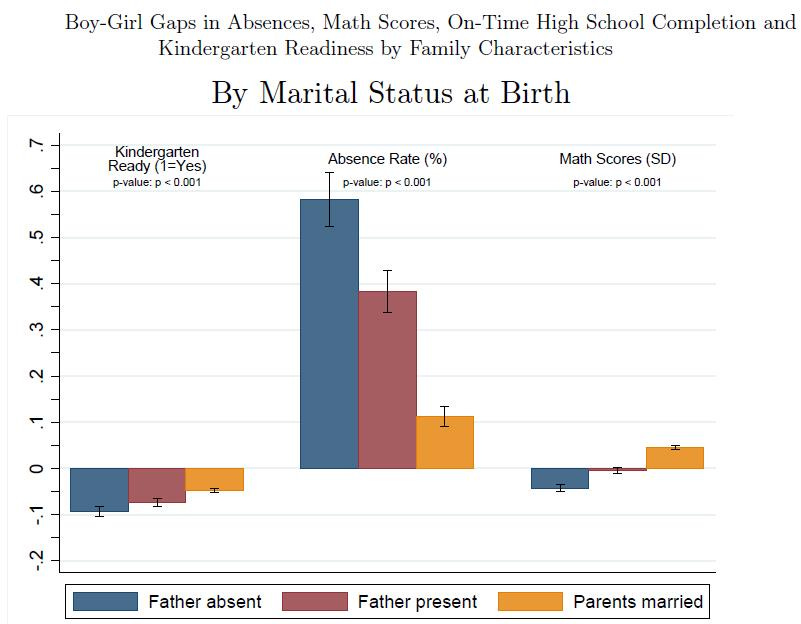

Boys particularly benefit when their married fathers live with the family, as boys are particularly hard-hit by the absence of a father. MIT economist David Autor and his colleagues have shown that, compared with less-advantaged girls, less-advantaged boys “have a higher incidence of truancy and behavioral problems throughout elementary and middle school, exhibit higher rates of behavioral and cognitive disability, perform worse on standardized tests, are less likely to graduate high school, and are more likely to commit serious crimes as juveniles.”

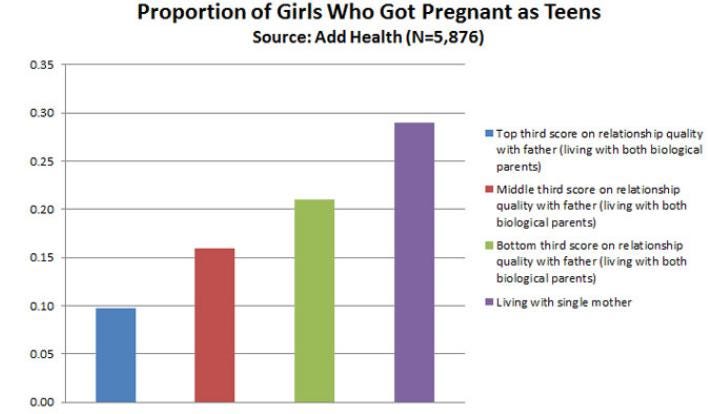

And regarding girls, daughters of fathers with whom they have a good-, or even a poor-, quality relationship get pregnant as teens less frequently.

These are all non-financial benefits of engagement with a father. As Kearney writes:

The absence of a father from a child’s home appears to have direct effects on children’s outcomes—and not only because of the loss of parental income. Nonfinancial engagement by a father has been found to have beneficial effects on children’s outcomes. A 2006 study using data from an earlier NLSY (the 1979 cohort) found that children in single-mother families exhibited worse behavioral outcomes than children from two-parent families, even after accounting for individual characteristics such as the child’s race and ethnicity and the mother’s educational attainment and age at first birth … A 2013 comprehensive review of the academic research on the causal effect of not having a father in one’s home concluded that a father’s absence has a negative causal effect on children’s social-emotional development, in particular by increasing externalizing behaviors, which are defined as disruptive, harmful, or problem behaviors directed outward—things like getting into fights or bullying … [M]arried dads tend to spend more time with their children than unmarried dads. In the 2019 American Time Use survey, married dads reported an average of 8.0 hours in dedicated childcare activities and 30 hours with their children per week. Unmarried dads reported 5.9 and 23.8 hours per week, respectively. As with moms, this marriage gap in time spent with children is observed for dads of all three education levels …

Kearney continues:

Boys from disadvantaged homes are more likely to get in trouble in school and with the criminal justice system; girls from disadvantaged homes are more likely to become young, unmarried mothers. These children grow up to have children who are more likely to be born into disadvantaged situations. Social mobility is undermined, and inequality persists across generations.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll explore the many observed beneficial outcomes for children of two-parent families.