The Two-Parent Privilege – Part 1

Introduction to the vast benefits of two parents to children.

As we saw at the end of the last essay series, the development of the monogamous two-parent nuclear family in the West significantly contributed to the development of even larger societal trends, including the growth of individualism and democracy over the last several centuries. But what have two-parent married couples done for us lately? That’s the subject of this series of essays.

Wherever anyone or any institution is discussing virtually any sort of public policy, there’s an elephant in the conference room. And that elephant is the two-parent married family. While many policymakers would like to ignore it, that elephant bursts through the data as soon as one takes a peek.

As economist Melissa Kearney of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology writes in her book The Two-Parent Privilege: How Americans Stopped Getting Married and Started Falling Behind:

There are all kinds of families and all kinds of households. People make their families work in all different ways, with various arrangements. The ways in which all of our families are different— with their own personalities, quirks, routines, and traditions— are part of what makes them so special. And part of what makes family so deeply personal is that exactly how any one of them works (assuming nobody is being harmed) is really no one else’s business. It is a separate question, however, how the structures of different families can deliver different benefits to children— and, in the aggregate, to society. It is reasonable to argue, for example, that a household with two parents has a greater capacity to provide financial and nonfinancial resources to a child than a one- parent household does. To argue this is not to judge, blame, or diminish households with a single parent; it is simply to acknowledge that (1) kids require a lot of work and a lot of resources, and (2) having two parents in the household generally means having more resources to devote to the task of raising a family. I have studied US poverty, inequality, and family structure for almost a quarter of a century. I approach these issues as a hardheaded—albeit softhearted—MIT-trained economist. Based on the overwhelming evidence at hand, I can say with the utmost confidence that the decline in marriage and the corresponding rise in the share of children being raised in one-parent homes has contributed to the economic insecurity of American families, has widened the gap in opportunities and outcomes for children from different backgrounds, and today poses economic and social challenges that we cannot afford to ignore—but may not be able to reverse.

Regarding the elephant in the conference room, Kearney writes:

Marriage is the most reliable institution for delivering a high level of resources and long-term stability to children. There is simply not currently a robust, widespread alternative to marriage in US society. Cohabitation, in theory, could deliver similar resources as marriage, but the data show that in the US, these partnerships are not, on average, as stable as marriages. (Another possible interpretation of these data: relationships are inherently difficult, and marriage provides an extra layer of institutional inertia that keeps them in place where simple cohabitation might not.) … [O]ver the past 40-plus years, American society has engaged in a vast experiment of reshaping the most fundamental of social institutions—the family—and the resulting generations of data tell us in no uncertain terms how that has played out for children … We will not be able to meaningfully improve the lives of children in this country, nor address the vast and growing level of inequality between kids who are born into more highly educated, higher-income homes and those who are not without confronting the reality that family life is crucial and that divergent family structures are a key driver of widening class gaps.

Yet as Nobel Prize-winning University of Chicago economist James J. Heckman, internationally recognized for his groundbreaking research on early childhood, said in an April, 2021, interview:

I think what we really have come to understand is that some of the major growth of inequality doesn’t only have to do with hourly wage rates at the factory. It also has to do with the change in family structure in the larger society. More single-parent families. And what does that mean? It often means that the mother faces the burden of supporting that child alone — she is really under stress — financial stress. And the single-parent family has fewer resources, so as single-parent families grow, inequality itself grows … So the family is a major driver. That’s the part that’s the third rail of American policy — nobody wants to talk about the family, and the family is the whole story. The family is the whole story. And it’s a whole story about a lot of social and economic issues.

As Kearney explains:

The share of American adults who are married is at a historic low. Among adults ages 30 to 50, in 2020, 60% of men and 63% of women were married. In 1980, the corresponding shares were 79% and 76%. That’s a 24% decrease among men and a 17% decrease among women. Going back another decade, the decline is even more dramatic—the shares married in 1970 were 87% of men and 83% of women. This reduction in the share of adults married reflects two trends: fewer adults are getting married now; and among those who do, they are marrying later in life than they used to. (Notably, the reduction is not driven by a rise in divorce. In fact, married couples today are less likely to get divorced than they were in the 1980s.)

Regarding divorce, Kearney writes of its bad effects on children:

To this question of how divorce affects children’s outcomes, scholars who have studied the impact of divorce on kids’ well-being have generally found that children who experience a parental divorce exhibit more emotional and behavioral problems compared to kids whose parents stay together. A 2004 study by MIT economist Jonathan Gruber identified the causal effect by designing a study centered on unilateral divorce laws—state laws allowing one spouse to end a marriage without consent of the other, which became more common during the 1970s and led to a sizable increase in the number of divorces in the US. Using data from the 1960, 1970, 1980, and 1990 US censuses (so, before and after the laws were implemented), Gruber found that this legal change led to more divorces and had the effect of worsening outcomes for children; namely, as a result of the increased incidence of parental divorce, children wound up having lower levels of education, lower levels of income, and more marital churn themselves (both more marriages and more separations), as compared to similarly situated children who did not live in places where unilateral divorce laws were in effect.

Researchers have found that divorce has significant negative effects on children’s well-being in adulthood:

Using four cross-sectional data files for the United States and Europe we show that Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) have a significant impact on subjective wellbeing (SWB) in adulthood … [P]arental separation or divorce … have long-term impacts on wellbeing … The parental divorce variable is statistically significant and positive for both bad mental and physical health days and distress.

Still, divorce is less of a social problem in that the divorce rate, while it rose a bit after the 1960's, has generally declined in recent decades as those who are married tend to stay married.

More recent data also show the divorce rate has declined. The divorce rate has fallen by nearly 25% over the last decade such that there are about 15 divorces per 1,000 married people today, about the same rate as in 1970 and surveys show Americans are less tolerant of divorce today.

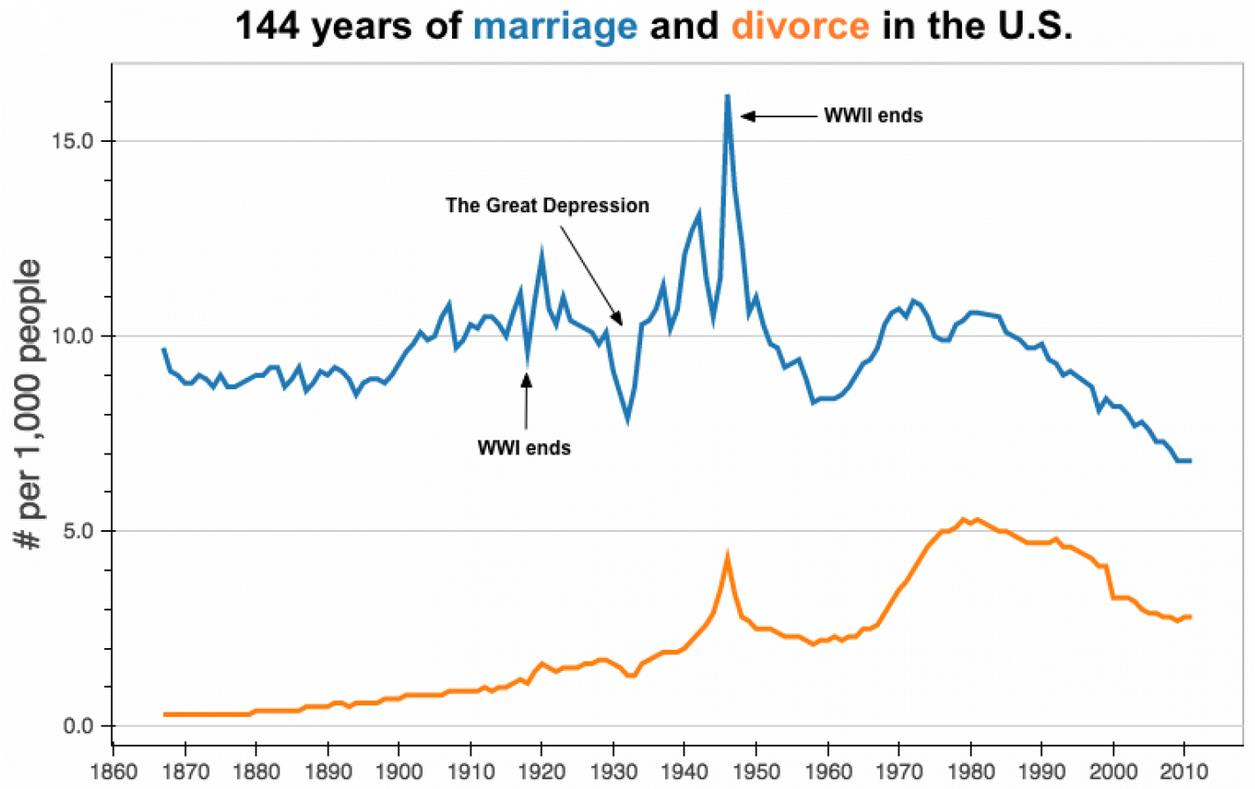

The following chart shows the marriage and divorce rates per 1,000 people over the last century and a half.

Back to marriage rates, the COVID lockdowns did not help. Researchers at Texas Tech and the University of Maryland found that the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with a large decrease in marriages, stating:

In the social upheaval arising from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, we do not yet know how union formation, particularly marriage, has been affected. Using administration records—marriage certificates and applications—gathered from settings representing a variety of COVID-19 experiences in the United States, the authors compare counts of recorded marriages in 2020 against those from the same period in 2019. There is a dramatic decrease in year-to-date cumulative marriages in 2020 compared with 2019 in each case. Similar patterns are observed for the Seattle metropolitan area when analyzing the cumulative number of marriage applications, a leading indicator of marriages in the near future. Year-to-date declines in marriage are unlikely to be due solely to closure of government agencies that administer marriage certification or reporting delays. Together, these findings suggest that marriage has declined during the COVID-19 outbreak and may continue to do so, at least in the short term.

In previous essays we explored the increasingly disproportionate share of women over men in higher education, a disparity that extends down to teachers in the public school system. And those women who don’t end up with college degrees constitute the larger part of single parent families. As Kearney writes:

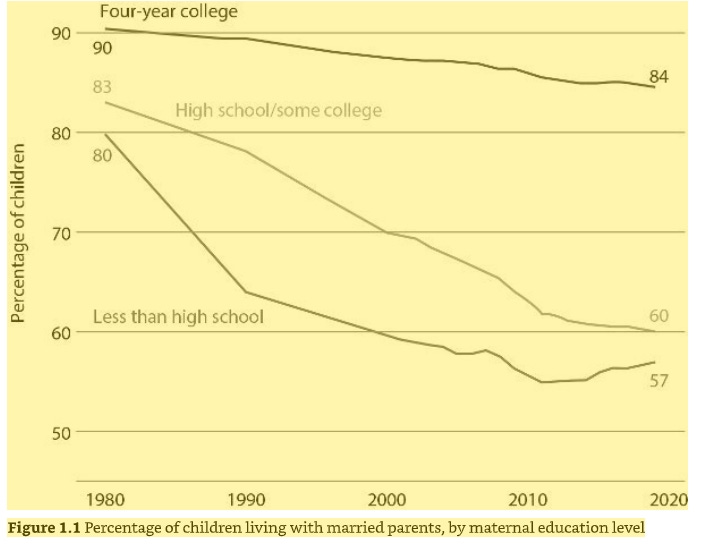

How should we think about family structure now that single motherhood is so much more common and extends to so many? Why are so many adults forgoing marriage, even when they have children? How are these trends affecting children from different backgrounds? … In 2019, only 63% of children in the US lived with married parents, down from 77% in 1980. This decline has not been experienced equally across the population. There has been little change, for example, in the family structure of children whose mothers have a four-year college degree: In 2019, 84% of children whose mothers had four years of college lived with married parents, a decline of only 6 percentage points since 1980. Meanwhile, only 60% of children whose mothers had a high school degree or some college lived with married parents, a whopping 23 percentage point drop since 1980. A similarly large decline occurred among children of mothers who didn’t finish high school; the share of children in this group living with married parents fell from 80% in 1980 to 57% in 2019. Figure 1.1 plots these trends.

Figure 1.1 Percentage of children living with married parents, by maternal education level SOURCE: Author’s calculations using 1980 and 1990 US decennial census and 2000–2019 US Census American Community Survey.

Data show conclusively that parents are not cohabitating without marriage in a way that remotely accounts for the decrease in two-parent married households. These kids are more often living with one parent. What’s more, data show that these trends are highly correlated with the parent’s education: The share of children living in two-parent homes is 71% when the mother has only a high school degree and 70% when she does not have a high school degree. A much higher share, 88%, of children of mothers with a four-year college degree live in a two-parent home.

On the other hand, as Kearney writes:

Among children of college-educated mothers over the last 40 years, the share living with married parents hasn’t changed much. In 1980, 90% of children of college graduates lived with married parents; in 2019 that number was holding strong at 84%. In contrast, among children of mothers with a high school degree or some college (but not a four-year college degree), only 60% lived with married parents in 2019—a huge drop from the 83% who did in 1980. This middle-education group accounts for the largest share of children today, which makes their situation very relevant to what is happening at a population level in the US today. Similar declines have occurred for children whose mothers have less than a high school degree, with less than 60% living with married parents, down from 80% in 1980 … The decline in marriage has been driven by a decline in marriage among those without a college degree … Granted, some of this narrative-fitting does reflect actual trends—college-educated adults do move around more for economic opportunity, and they do put in longer hours at work. But they are actually less likely to remain single than those with less education. For women, this reflects a reversal from trends in earlier decades. Overall, both men and women with college degrees are now more likely to be married than others.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll explore whether single parents with higher incomes make a significant difference in children’s outcomes, or whether there are other, more significant factors at work.