The Rule of Law – Part 6

The influence of lawyers in America today.

Continuing this essay series on the rule of law, this essay will focus on the influence of lawyers in America today.

In the previous essay, we described how lawyers in America are allowed to coerce money settlements from innocent people by filing frivolous lawsuits without penalty. Lawyers, under prevailing contingency fee arrangements, generally take one-third of these settlement awards and use them to pay for more lawsuits, and many use them to fund the campaigns of political candidates who oppose reforms of the current system. The lobbying arm of the trial lawyers is called the American Association for Justice, and they give 97% of their donations to Democratic candidates.

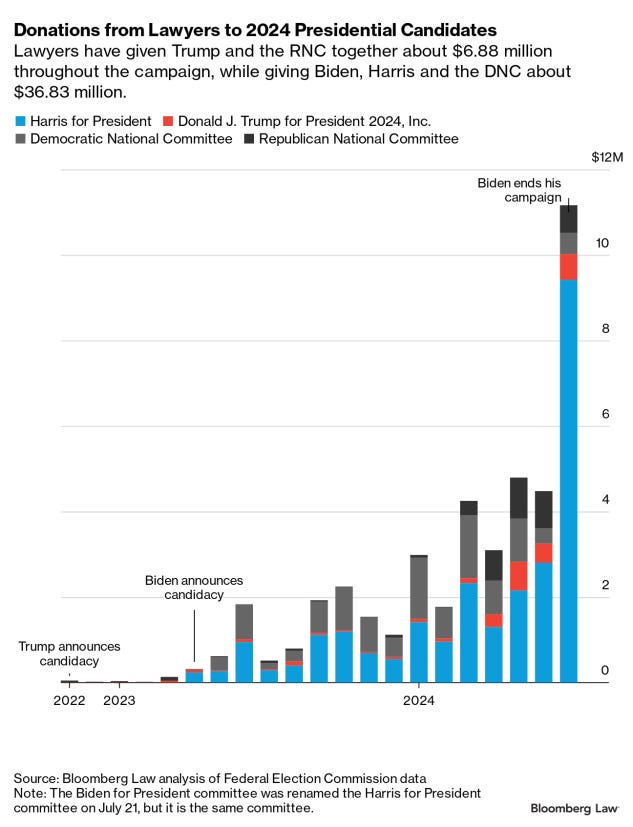

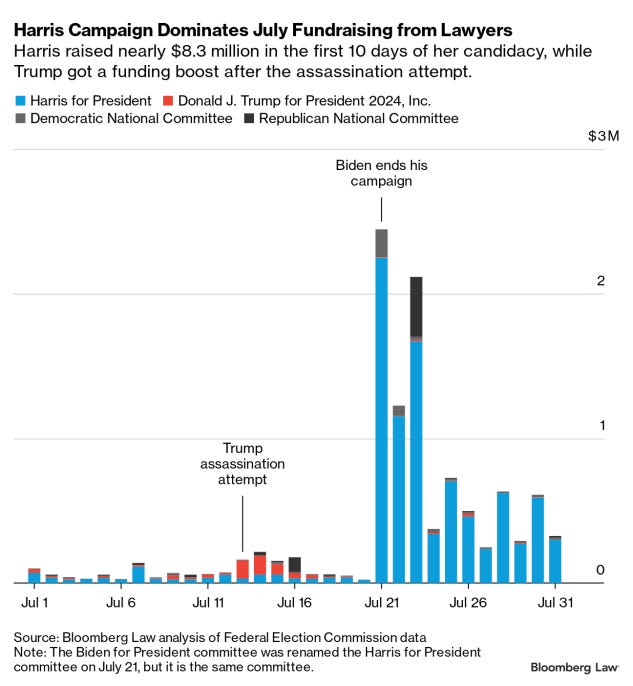

As a recent article in Bloomberg Law, titled “Lawyers Give More to Harris in 10 Days Than Trump in Entire Race” states:

Lawyers gave more to Vice President Kamala Harris in the first 10 days of her presidential campaign than to former President Donald Trump in nearly two years, according to Federal Election Commission records … Lawyers historically have given more—and in recent elections, much more—in individual contributions to Democrats than Republicans in presidential elections. And lawyers have also given significantly more to Biden than Trump. The Democratic National Committee and the Democratic campaign combined raised about $36.83 million from lawyers since Biden announced his run for re-election on April 25, 2023. That amounts to donors who listed attorney or lawyer as their occupation contributing about $5.35 to the Democratic ticket and national committee for every $1 contributed to the Republican ticket and national committee. That is not an outlier. In 2012, Barack Obama and the DNC got $2.96 for every $1 Mitt Romney and the RNC got from lawyers. In 2016, Hillary Clinton and the Democrats got $17.74 for every $1 to Trump and the Republicans. And in 2020, lawyers gave $5.61 to Biden and the DNC for every $1 to Trump and the RNC. All of those figures are according to FEC records from when the candidate announced they were running through the end of July that election year.

“Now it seems hard to find any of the largest firms that are right-leaning,” said Derek Muller, election law professor at the University of Notre Dame Law School. “It’s just been a kind of slow and steady drift over the last several presidential cycles.”

As the Wall Street Journal writes:

We always knew trial lawyers were filling their pockets, but it’s still a surprise to learn how much they’ve been emptying ours. The total economic cost of the U.S. tort system in 2020 was $443 billion, according to a recent study by the Chamber of Commerce Institute for Legal Reform. That’s 2.1% of GDP, and it works out to $3,621 per household. Only a small percentage of American families are involved in tort cases or class-action lawsuits in a given year, but the burden of jackpot payouts is carried by nearly everyone. The costs spread through the economy in the form of higher insurance premiums that fall on nearly every family, either directly (car insurance) or indirectly (medical malpractice or product-liability insurance). And costs are rising. Between 2016 and 2020 the tort system grew 6% a year, the study says, more than inflation and GDP growth. Commercial liability grew the fastest, at 7% a year. Also alarming is that only half the money goes to injured parties. “We estimate that only 53 percent of the total expenditures of the tort system were paid to claimants,” the authors write. In other words, “for every dollar paid in compensation to claimants, 88 cents were paid in legal and other costs.” … We’re hard pressed to think of another industry whose existence costs the average American family more than $3,000 a year. Too bad there isn’t a way to sue the plaintiffs bar for a refund.

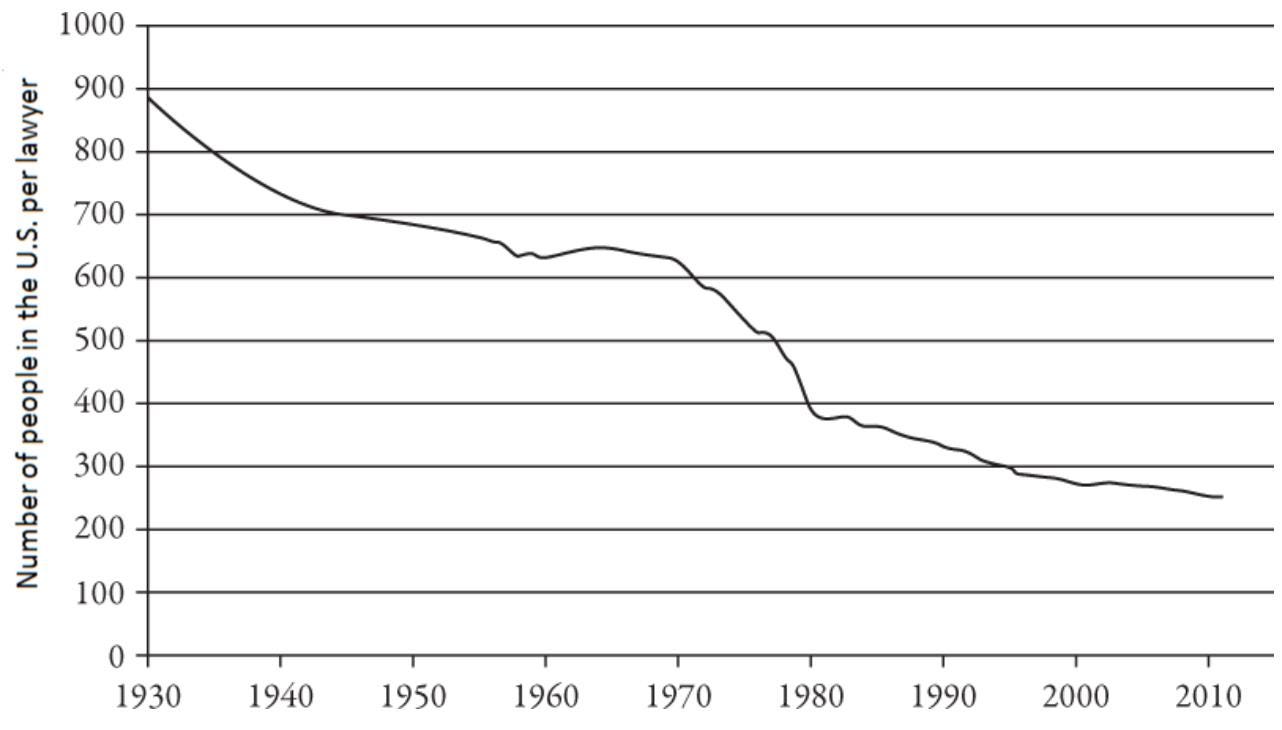

The number of lawyers per capita in the U.S. has steadily increased such that today there is about one lawyer for every 250 people in America.

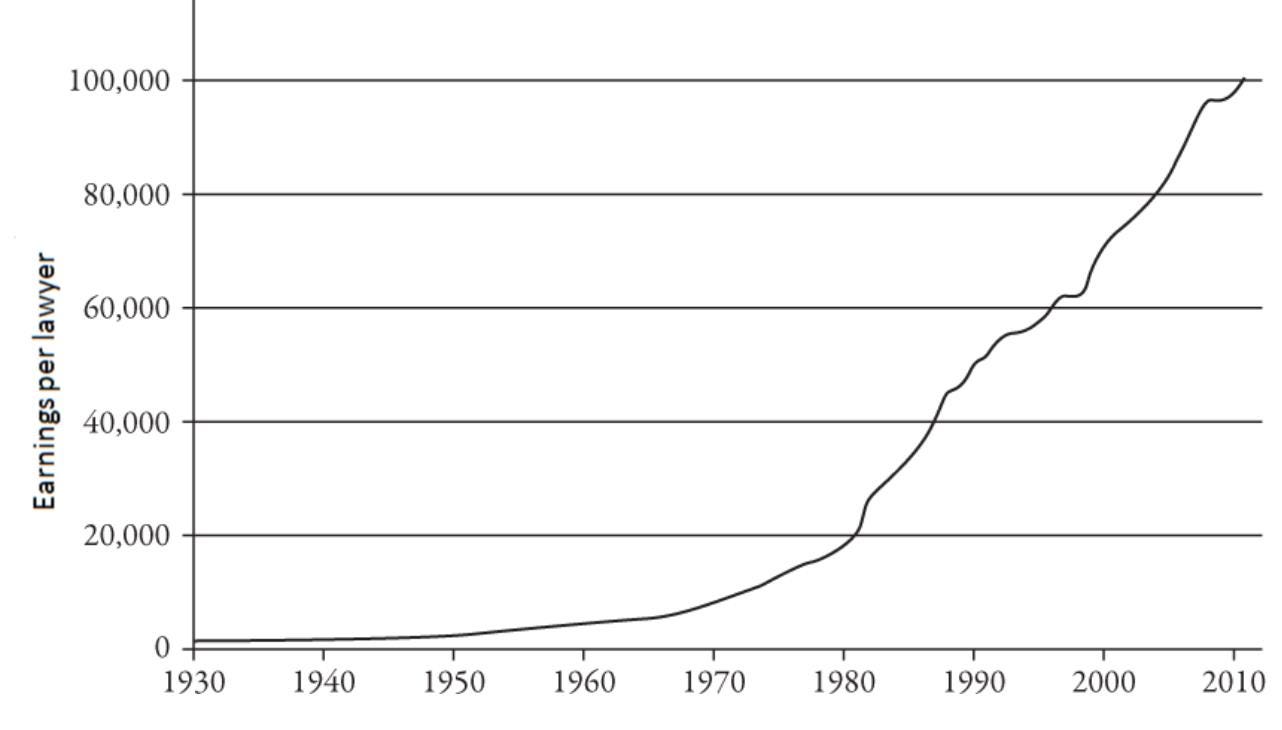

As there came into being more lawyers, their earnings per lawyer grew, and lawsuits proliferated.

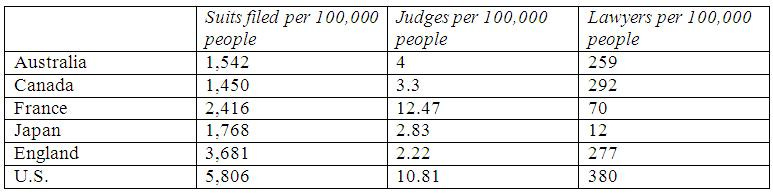

Compared to other countries, the U.S. has far more lawsuits filed per capita, and more judges and lawyers per capita.

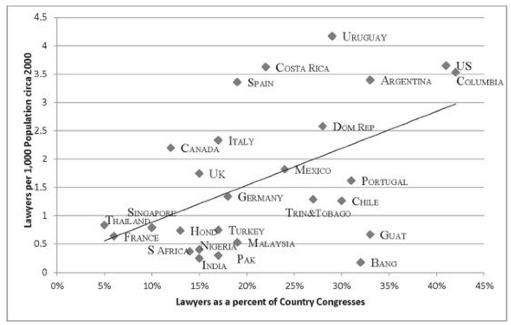

The U.S. also has one of the highest rates of lawyers serving in its national legislature.

Lawyers who file lawsuits against American companies use their unique ability to leverage government power to the disadvantage of American industry. An extensive and unique international survey of litigation trends found that U.S.-based respondent companies reported a more litigious business environment than their international peers, with 55 percent facing more than five lawsuits filed against their companies in the previous 12 months, compared with 23 percent in the United Kingdom and 22 percent in Australia. Just 18 percent of U.S. companies reported no lawsuits, compared with 42 percent in the United Kingdom and 36 percent in Australia.

Research has also shown that the fear of excessive lawsuits can deter companies from innovating. Even manufacturers of the simple zipper, when it first entered the market, were subject to fears of liability. One historian who wrote a book on the history of the zipper, citing a 1937 internal company memo, concluded that “Retailers were made to worry that they could be held legally liable if a man injured himself with the newfangled machine on his trouser fly.” Manufacturers face that issue today as they decide when, if ever, to market, for example, driverless or autonomous cars.

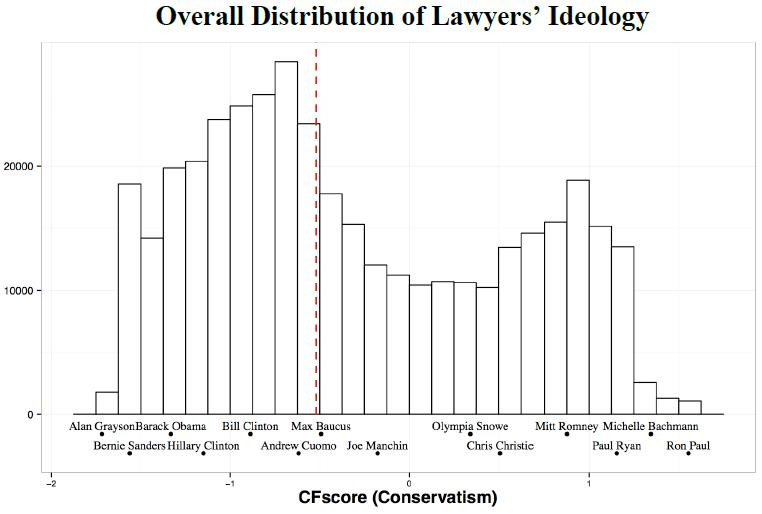

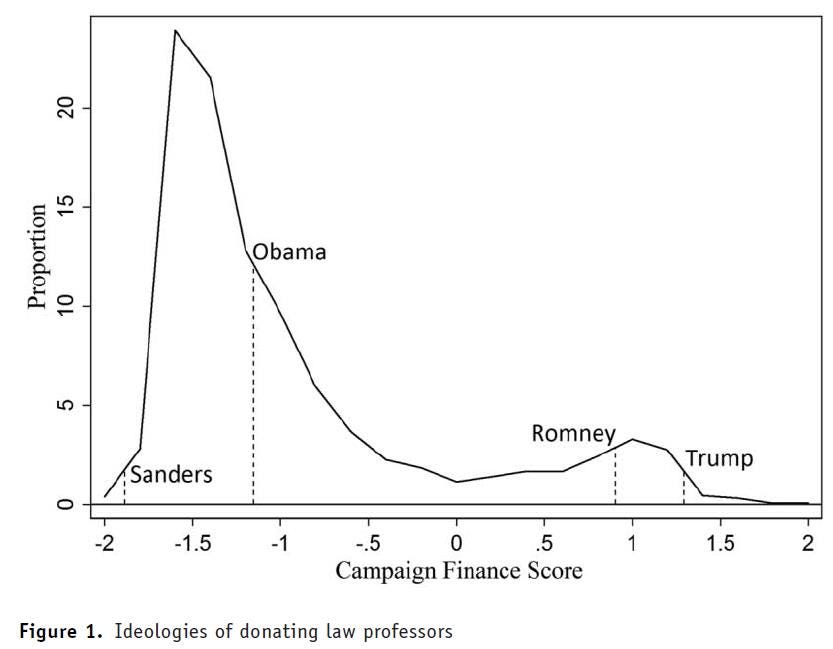

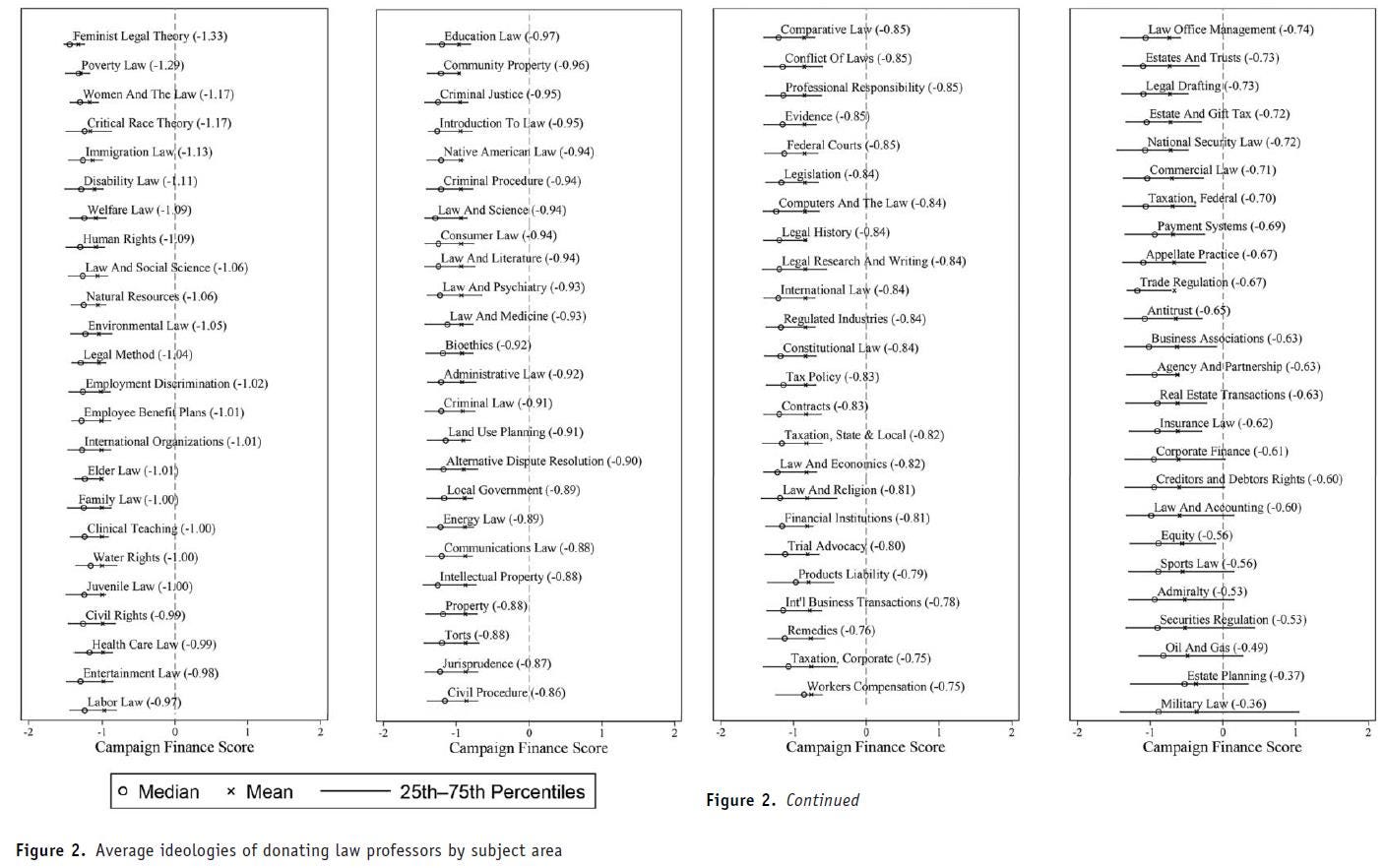

Ideologically, beyond political money donations, the largest ideological survey of lawyers shows that lawyers lean heavily to the left.

Large law firm pro bono programs also heavily favor lawsuits with left-of-center-goals.

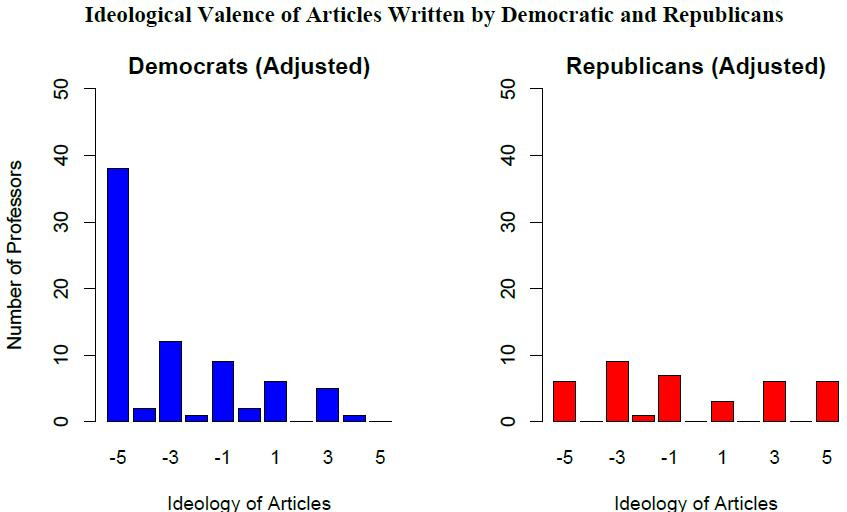

Regarding law schools, researchers have also found that Democratic law professors are much more likely to write articles biased toward liberal results than Republican law professors are likely to write articles biased toward conservative results. The researchers reported that:

no one has used statistical methods to test the … hypothesis that legal scholarship reflects the political biases of law professors. This paper provides the results of such a test. We find that, at a statistically significant level, law professors at elite law schools who make donations to Democratic political candidates write liberal scholarship, and law professors who make donations to Republican political candidates write conservative scholarship. These findings raise questions about standards of objectivity in legal scholarship.” However, the researchers also found that “Professors who are Democrats (adjusted) -- shown in the left panel -- have an average article ideology of -2.67 with a 90% confidence interval of -3.13 to -2.21. Using a t-test, we can say that this is statistically different from zero (p-value < 0.00). Professors who are Republicans (adjusted)—shown in the right panel—have an average article ideology of 0.17 with a 90% confidence interval of -0.72 to 1.10. For these professors, we cannot reject the possibility that the true net ideology of their articles is zero (p-value = 0.72). In other words, our data suggest that Democrats in our sample do not write articles that are on balance neutral, but that Republicans in our sample may write articles that are on balance neutral.

The researchers conclude:

if it is in fact the case that Republicans write less ideologically biased scholarship than Democrats do, then one would naturally ask why … The most plausible explanation is that if the dominant ethos in the top law schools is liberal or left-wing, then Republicans are likely to conceal their ideological views in their writings. Republican professors might fear that scholarship that appears conservative may be rejected by left-leaning law review editors, and disparaged or ignored by their colleagues, which will damage their chances for promotions, research money, and lateral appointments. This would explain why even non-donors tilt left. Republicans could suppress their ideological views by avoiding controversial topics, taking refuge in fields that have little ideological valence, focusing on empirical or analytical work, or simply writing things that they don’t believe.

The researchers also found that:

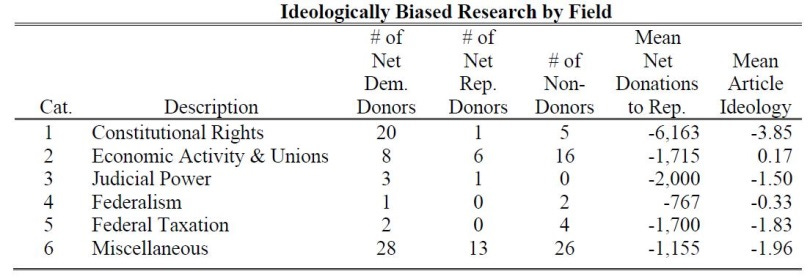

[t]he data presented in [the table below] suggest that constitutional rights scholars are less ideologically diverse than other legal scholars. Among constitutional rights scholars, 77% are net Democratic donors, and 4% are net Republican donors. In the rest of the sample, 40% are net Democratic donors, and 20% are net Republican donors. It also shows that constitutional rights scholars are more likely to produce biased research (mean of -3.85 conservative articles) than Republican and Democratic scholars in other fields (mean of -1.35 conservative articles).

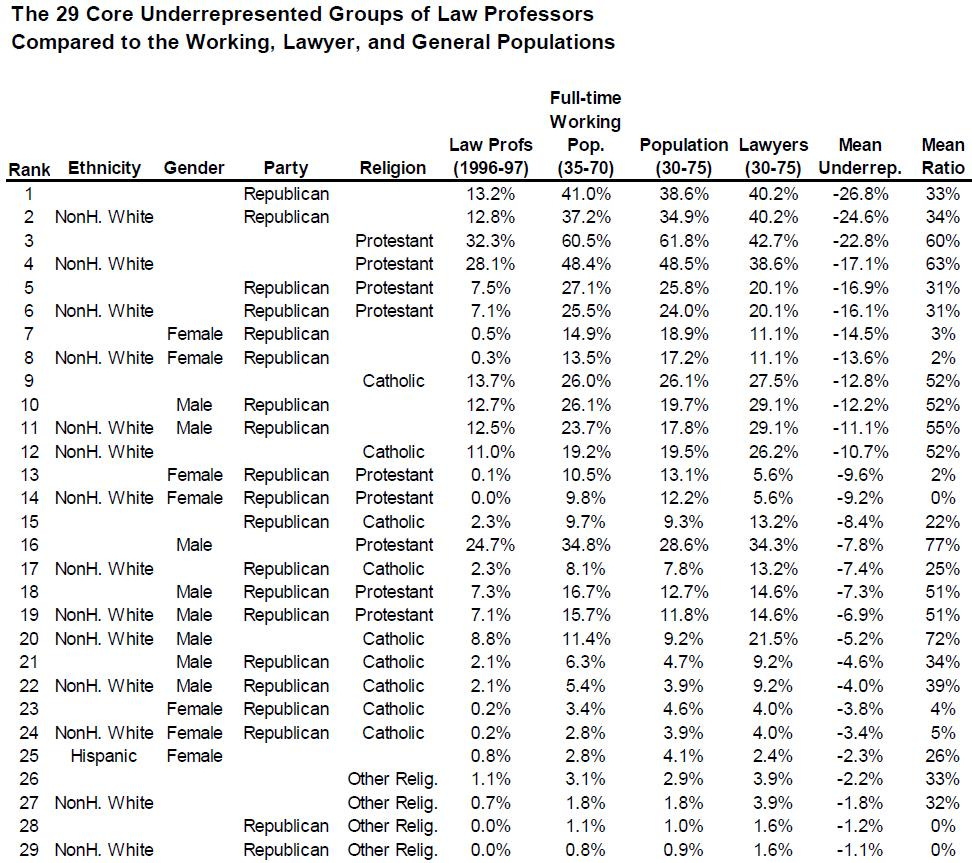

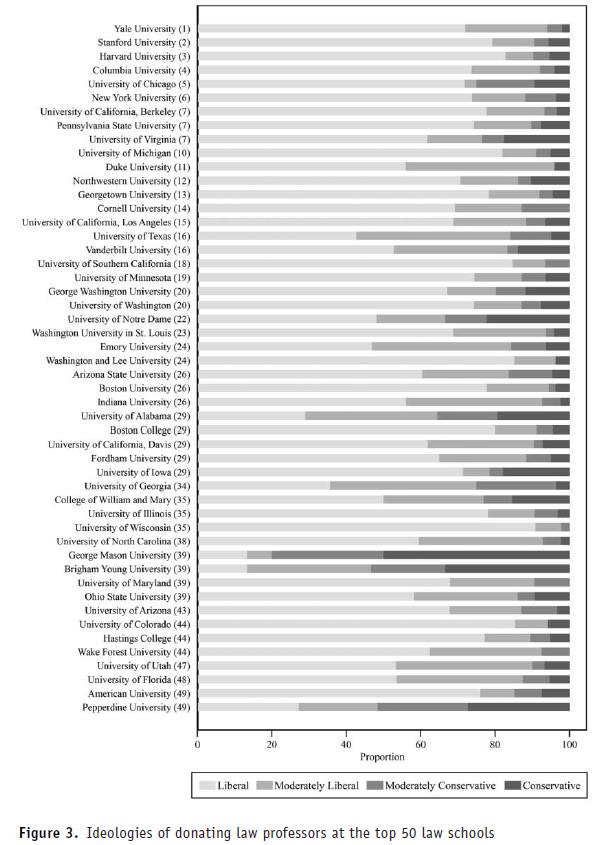

The most underrepresented demographic groups among law school professors, compared to their percentage of the population as whole, are Republicans (both male and female), Protestants, and Catholics. The 9 percent of the U.S. population that is neither Republican nor Christian generates 51 percent of law professors.

As some researchers have reported:

[U]pon comparing conservative/libertarian law professors hired from 2001-2010 with equally-credentialed liberal law professors, conservatives/libertarians end up, on average, at a law school ranked 12-13 spots lower (i.e., less prestigious) ... Thus, while there may be other mechanisms causing the dearth of conservative/libertarian law professors in the legal academy, those who do make it in the door appear to experience discrimination based on political orientation.

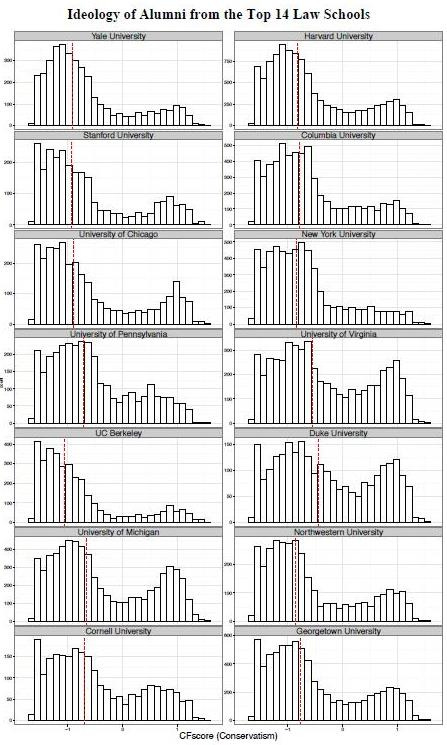

Relatedly, alumni from the top law schools lean sharply to the left.

A 2018 study found the following ideological disparities among law professors.

The “limited liability” corporate form, which limits lawsuits against owners and investors in companies, was described by Harvard University President Charles Eliot as “by far the most effective legal invention for business purposes made in the nineteenth century,” and the President of Columbia University, Nicholas Murray Butler, said “the limited liability corporation is the greatest single discovery of modern times … Even steam and electricity are far less important than the limited liability corporation, as they would be reduced to comparative impotence without it.” Alex Tabarrok has written “Without the limited liability company, it would probably have been much more difficult to raise large amounts of capital. As a result, without limited liability, markets would be at a great disadvantage compared to the state in conducting economic activity on a large scale. Thus … the limited liability company [is] among the technological/legal institutions that have made a free society possible …” Some have also concluded that the internet revolution, including the creation of companies such as Google, Facebook, Tumblr, Twitter, Reddit, Craigslist, YouTube, Instagram, eBay, and Amazon, could never have occurred were it not for a federal statute that prevented them from being sued for what others uploaded to their sites. That federal statute, enacted in 1996, reads: “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.”

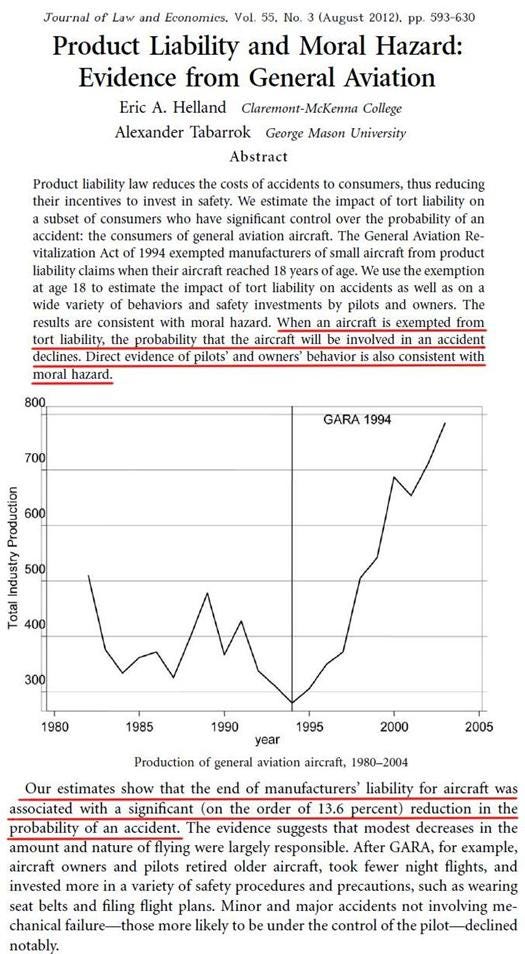

Beyond the disadvantage lawsuits place on American industry, they also tend to reduce the incentive of individual citizens to exercise personal responsibility. One study found that in states that enacted reforms that reduced manufacturers’ liability between 1981 and 2000 there were 24,000 fewer accidental deaths, compared to states that did not enact such reforms. Other research found that women may be less likely to be given CPR by bystanders due to bystander fears of being accused of potentially inappropriate touching or exposure or sexual assault. Research also shows that when people are limited in their ability to blame others through lawsuits, they exercise more personal responsibility, as one study found that when the liability of older aircraft manufacturers was limited by Congress, not only did the production of aircraft rise, but the incidence of aircraft accidents declined, as pilots and aircraft owners took more care to avoid accidents.

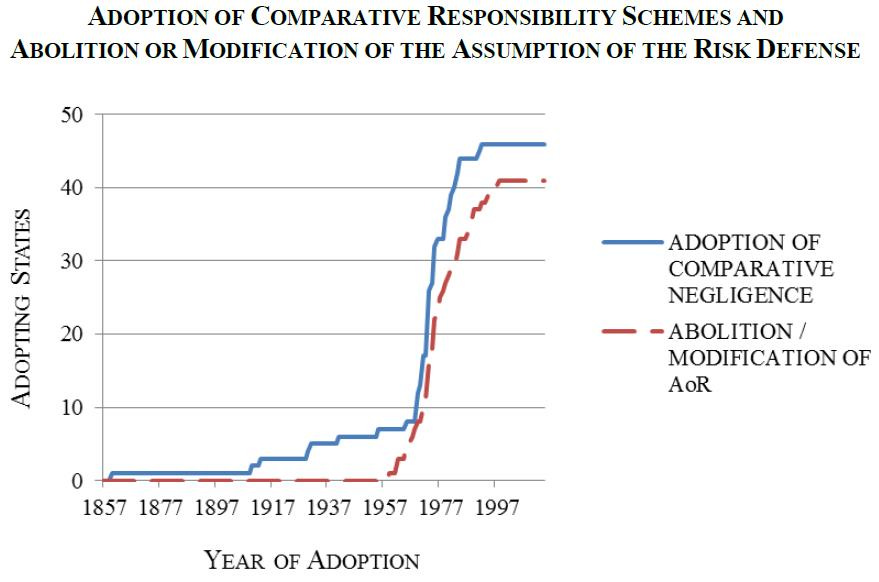

Recent trends toward blaming others for injury — in cases in which plaintiffs could easily have avoided injury — discourage taking personal responsibility when doing so would lead to fewer injuries. In the 1960’s, the legal concept of “assumption of risk” was abolished or modified, shifting responsibility to people or entities other than those who engaged in the risky activity.

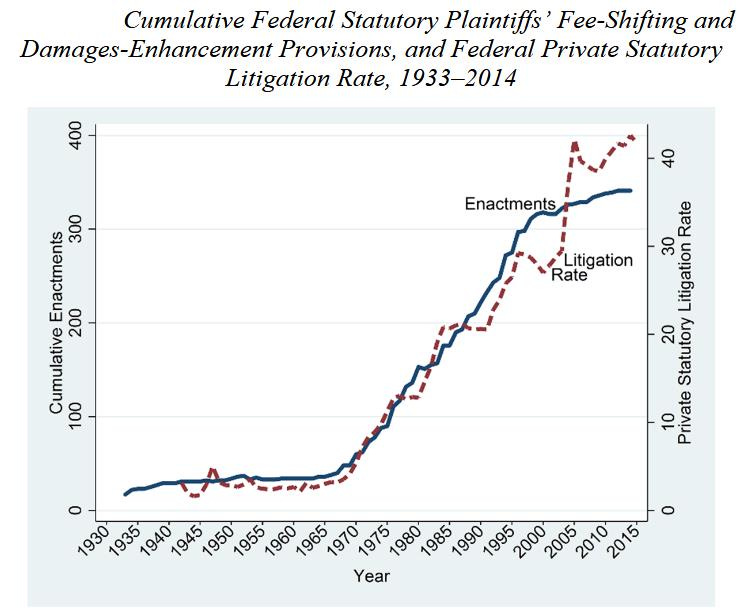

Congress has encouraged litigation by enacting more and more laws since the 1960’s that allow plaintiffs who file suit to recover their legal fees if they win, but do not allow defendants to recover such fees when they win.

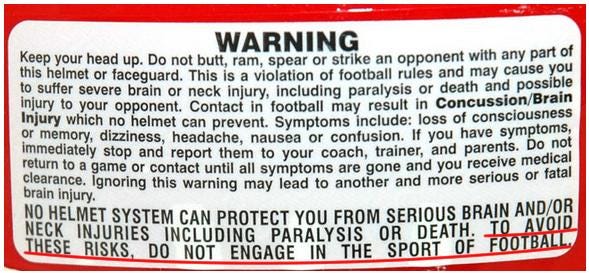

Due to a fear of frivolous lawsuits, absurd warning labels have been placed on many common products.

A football helmet manufacturer has even placed a warning label on them that warns against playing football.

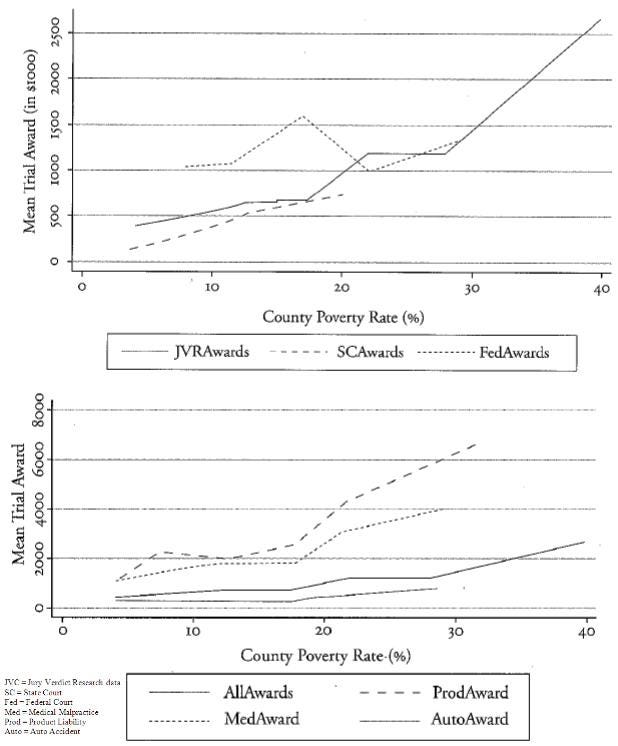

And juries appear to use lawsuit awards as a means of wealth redistribution. When injuries and other factors are controlled for, trial awards grow larger when the counties in which the juries sit have higher poverty rates.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll explore how a series of legal reforms enacted over the last two decades have tended to reduce litigation abuse and encourage innovation.