The Rule of Law – Part 5

How the American legal system allows coercing money from innocent people.

Continuing our essay series on the rule of law, this essay will focus on some unique features and trends within the American legal system. The following draws from a law review article of mine entitled “The Difference Between Filing Lawsuits and Selling Widgets: The Lost Understanding that Some Attoryners’ Exercise of State Power is Subject to Appropriate Regulation,” which appeared in the Pierce Law Review (now the University of New Hampshire Law Review).

As I wrote in that article, and in more recent testimony to Congress, today in America, attorneys who file lawsuits can, by simply filing a complaint at their unfettered discretion, immediately subject defendants to the threat of a default judgment (a judgment for the plaintiff entered after the defendant fails to timely answer or otherwise appear). That threat of a default judgment – which, importantly, is enforced by the government -- forces defendants to spend money and resources toward their defense in order to avoid the default judgment, even when defendants are wholly innocent. That dynamic results in a situation in which a defendant will be made to pay any amount to the plaintiff in settlement, provided the settlement demanded is less than the defendant’s costs of defense and the plaintiff’s attorneys’ costs for filing the case (which are minimal). The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, for example, place no limits on the ability or authority of a lawyer to file a complaint. Under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 4, once a complaint is filed, the court clerk sends a summons to the plaintiff or their attorney, who then serves the summons and a copy of the complaint on the defendant. The summons carries with it the threat of a default judgment if the defendant does not respond, thereby requiring a response, however innocent the defendant might be.

As legal and economic professors have described the situation under current law:

[T]he plaintiff may choose to file a claim at some (presumably small) cost. If the defendant does not then settle with the plaintiff and does not, at a cost, defend himself, the plaintiff will prevail by default judgment ... Given the model and the assumption that each party acts in his financial interest and realizes the other will do the same, it is easy to see how nuisance suits can arise. By filing a claim, any plaintiff, and thus the plaintiff with a weak case, places the defendant in a position where he will be held liable for the full judgment demanded unless he defends himself. Hence, the defendant should be willing to pay a positive amount in settlement to the plaintiff with a weak case ...

These commentators point out that defendants face a form of extortion because “to defeat a claim, the defendant will have to engage in actions that are frequently more expensive than the plaintiff’s cost of making the claim, for the defendant will have to gather evidence supporting his contention that he was not legally responsible for harm done to the plaintiff or that no harm was actually done.” The same commentators offer the following illustration:

Suppose, for instance, that the plaintiff files a claim and demands $180 in settlement. The defendant will then reason as follows. If he settles, his costs will be $180. If he rejects the demand and does not defend himself, he will lose $1000 by default judgment. If he rejects the demand and defends himself, the plaintiff will withdraw, but he will have spent $200 to accomplish this. Hence, the defendant’s costs are minimized if he accepts the plaintiff’s demand for $180; and the same logic shows that he would have accepted any demand up to $200. It follows that the plaintiff will find it profitable to file his nuisance claim; indeed, this will be so whenever the cost of filing is less than the defendant’s cost of defense.

Under this dynamic, when an attorney files a case, the defendant is in a lose-lose situation from the beginning: the defendant can either pay the costs of defending the case, or lose the case entirely by doing nothing. All cases, simply by virtue of being filed, have an immediate “nuisance” value for the plaintiff that creates an inherently superior bargaining position for the plaintiff’s attorney. Attorneys have the unique power to subject innocent individuals to a situation in which simply paying off frivolous claimants through monetary settlements is cheaper than litigating the case.

In essence, in America, I could pay a small filing fee, hand you a complaint making a ridiculous claim against you, and say, “This case would cost you $10,000 to defend yourself and win, but you’d be out that money. Why don’t you just pay me $7,000 now, I’ll give a cut to my funders, and then I’ll go away, and that way, you’ll save $3,000 out of the $10,000 it would have cost you to litigate this case to victory.”

Attorneys know the mere filing of claims immediately subject defendants to significant legal costs of defense, and they will tend to use those costs of defense to their advantage. A legal system that allows attorneys unfettered authority to trigger inherent bargaining advantages, simply by virtue of their filing a complaint, should also limit attorneys’ ability to exploit this inherent bargaining advantage for their own personal gain, but that’s largely not the case today. As leading legal ethics expert Geoffrey Hazard once wrote in Social Responsibility: Journalism, Law, Medicine: The Legal and Ethical Position of the Code of Professional Ethics vol. 5 (1979), ”[t]he function of lawyer is closely related to the exercise of government power. We wish to control the exercise of government power through constitutions and laws. So also we wish to use constitutions and laws to control the exercise of the quasi-governmental power that is exercised through our profession.”

The Supreme Court has also noted the institutionally coercive role lawyers are allowed to play in society, stating:

As an officer of the court, a member of the bar enjoys singular powers that others do not possess; by virtue of admission, members of the bar share a kind of monopoly granted only to lawyers … [A]s an officer of the court, a lawyer can cause persons to drop their private affairs and be called as witnesses in court, and for depositions and other pretrial processes that, while subject to the ultimate control of the court, may be conducted outside courtrooms. The license granted by the court requires members of the bar to conduct themselves in a manner compatible with the role of courts in the administration of justice.

As another commentator has pointed out:

The state could require the attorney to submit for ex parte approval a proposed defendants list that includes constitutional rationales for naming each defendant. But the courts and legislatures have delegated these decisions to attorneys. By allowing discretion into procedural rules, the state grants decisional power to attorneys. These grants of discretion substitute the attorney’s decisions for those of a judge or other state officer or body.

And as another law professor has written:

The fundamental flaw in Rule 4(b) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure is that it delegates governmental power to a private individual to compel another to appear and defend, at significant cost and inconvenience, without either a preliminary inquiry by a judge or magistrate judge that the imposition on the defendant is reasonable, or a reliable practice of assessing the full costs imposed without proper justification retroactively if it turns out that the interference with the time and money of the person sued was not reasonable. This delegation of state power to hale people into court without safeguards is particularly anomalous because, as Judge Learned Hand famously reminded us, the greatest calamity that can befall a person, other than sickness or death, is to become involved in a lawsuit. The unsupervised power that Rule 4(b) delegates to private parties with a financial interest is incongruous. Many similar provisions under which the government summons someone to account for her actions are preceded by a preliminary judicial inquiry appropriate to the circumstances before the state intrudes on a person's most fundamental right: the right to be let alone. For example, we require a preliminary judicial inquiry into the bona fides of claims before: Issuing a warrant to search or seize; Summoning someone to answer criminal charges; Requiring someone to answer civil claims if brought in forma pauperis; Requiring someone to answer civil claims that may be brought in retaliation for exercise of their First Amendment rights (a so-called “strategic lawsuit against public participation” (SLAPP)); Requiring someone to produce documents or testimony in response to a government inquiry; and Requiring a government official to answer a petition for habeas corpus.

The key point here is that that sort of legal extortion relies on the government’s power to enforce the default judgment. No truly private business, relying solely on voluntary agreements in a free market, could rely on government power to its advantage in that way.

But one might ask, don’t people have a remedy when they’re the victim of frivolous lawsuits in America? No. Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 11 (which pertains to frivolous lawsuits) fails to provide an effective remedy. The current federal rule allows judges to deny the victims of frivolous lawsuits any compensation for the harm they suffered, even when the judge determines the lawsuit against them was legally frivolous. That’s because judges aren’t required to order that the victim of a frivolous lawsuit’s costs be paid back. Rule 11 doesn’t require any sanctions at all for the filing of frivolous lawsuits, as it states “the court may … impose an appropriate sanction.” Rule 11 uses the term “may,” not “shall.” As a result, the current Rule 11 goes largely unenforced, because the victims of frivolous lawsuits have little incentive to pursue additional litigation to have the case declared frivolous when there is no guarantee of compensation (even when the judge agrees the case is frivolous). Indeed, former Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, joined by Justice Clarence Thomas, said as much when he commented on the current wording of Rule 11, in which he stated it would eliminate a “significant and necessary deterrent” to frivolous litigation and “render the Rule toothless, by allowing judges to dispense with sanction [and] by disfavoring compensation for litigation expenses.”

Not only do the rules allow attorneys to sue whomever they choose, they allow them to decide on what grounds to sue, the types of damages to request, and the amount of money to demand. The attorney’s unlimited discretion to determine the amount sued for has significant consequences for defendants. University of Chicago law professor Cass Sunstein and Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman have compiled research from studies involving more than 8,000 jury-eligible citizens in Illinois, Colorado, Texas, Arizona, and Nevada showing that juries give higher awards when personal injury attorneys simply demand higher amounts, and settlement costs can be expected to rise with the threat of higher jury awards.

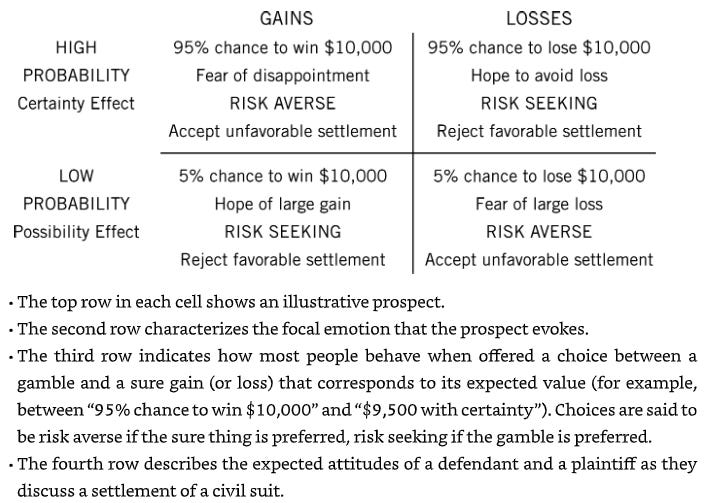

Daniel Kahneman also explores the coercive pressure to agree to settle frivolous cases under the rules of the American legal system in his own influential book Thinking, Fast and Slow. He uses this chart to make the following points:

Now consider “frivolous litigation,” when a plaintiff with a flimsy case files a large claim that is most likely to fail in court. Both sides are aware of the probabilities, and both know that in a negotiated settlement the plaintiff will get only a small fraction of the amount of the claim. The negotiation is conducted in the bottom row of the fourfold pattern. The plaintiff is in the left-hand cell, with a small chance to win a very large amount; the frivolous claim is a lottery ticket for a large prize. Overweighting the small chance of success is natural in this situation, leading the plaintiff to be bold and aggressive in the negotiation. For the defendant, the suit is a nuisance with a small risk of a very bad outcome. Overweighting the small chance of a large loss favors risk aversion, and settling for a modest amount is equivalent to purchasing insurance against the unlikely event of a bad verdict. The shoe is now on the other foot: the plaintiff is willing to gamble and the defendant wants to be safe. Plaintiffs with frivolous claims are likely to obtain a more generous settlement than the statistics of the situation justify … The decisions described by the fourfold pattern are not obviously unreasonable. You can empathize in each case with the feelings of the plaintiff and the defendant that lead them to adopt a combative or an accommodating posture. In the long run, however, deviations from expected value are likely to be costly. Consider a large organization, the City of New York, and suppose it faces 200 “frivolous” suits each year, each with a 5% chance to cost the city $1 million. Suppose further that in each case the city could settle the lawsuit for a payment of $100,000. The city considers two alternative policies that it will apply to all such cases: settle or go to trial. (For simplicity, I ignore legal costs.) If the city litigates all 200 cases, it will lose 10, for a total loss of $10 million. If the city settles every case for $100,000, its total loss will be $20 million. When you take the long view of many similar decisions, you can see that paying a premium to avoid a small risk of a large loss is costly.

Attorneys have this coercive power to extract settlements from innocent parties, and they are allowed to exercise it for their own financial gain. As Judge Richard Posner has explained, “the legal process relies for its administration primarily on private individuals motivated by economic self-interest rather than on altruists or officials.” Consequently, like all other economic actors, attorneys will tend to exploit situations to maximize their own utility. One way of doing that, of course, is by exploiting the inherent bargaining advantage the state allows them through rules authorizing attorneys to sue whomever they want for whatever they want, even when a lawsuit has no legal merit.

How did we get to this situation in America today? As I wrote in The Difference Between Filing Lawsuits and Selling Widgets:

The understanding that attorneys can exercise state power -- and the fear that power would be abused -- has ancient roots, as do laws seeking to limit such abuse. In ancient Rome, Tacitus described how the emperor Claudius fixed maximum attorneys’ fees at ten thousand sesterces because attorneys were considered to be doing the work of the state. Justinian in his Digests maintained the law limiting attorneys’ fees, and further banned contingency fees entirely. Since then, European law relied significantly on Roman law, and limits on attorneys’ fees remained the norm in Europe throughout its history, and later in America, driven largely by attorneys’ potential to abuse the litigation system. During the American Colonial period, lawyers were roundly despised. According to one historian, ”[i]n every one of the Colonies, practically throughout the Seventeenth Century, a lawyer or attorney was a character of disrepute and of suspicion … In many Colonies, persons acting as attorneys were forbidden to receive any fee . . . in all, they were subjected to the most rigid restrictions as to fees and procedure.” Early American observer Benjamin Austin wrote, “if we look through the different counties throughout the Commonwealth, we shall find that the troubles of the people arise principally from debts enormously swelled by tedious law-suits.” The Duc de La Rochefoucauld similarly observed, “[t]he ... inhabitants of New England. They are said to be very litigious … [T]here are, indeed, few disputes, even of the most trivial nature, among them, that can be terminated elsewhere than before a court of justice.” As one historian summarized the situation in early America, “[l]awsuits were often begun or continued for no other purpose than to embarrass an enemy by making him incur legal costs.” And as John Adams observed of the notoriously litigious town of Braintree, Massachusetts, “[t]hese dirty and ridiculous litigations have been multiplied, in this town, till the very earth groans and the stones cry out. The town has become infamous for them throughout the country.” Popular journalist William Duane of Philadelphia, wrote a pamphlet arguing that abusive litigation practices by lawyers “demand the more serious interference of the legislature, and the jealousy of the people” because lawyers “so manage justice as to engross the general property to themselves, through the medium of litigation …” +Fear that the legal profession would abuse its power to generate lawsuits was also reflected in limits on attorneys’ fees [in early America].

Statutory limits on attorneys’ fees prevailed until the mid-nineteenth century. Then, in 1848, the Field Code of Civil Procedure that governed practice in New York struck down all provisions “establishing or regulating the costs or fees of attorneys” and provided that “hereafter the measure of such compensation shall be left to the agreement, express or implied, of the parties.” The report recommending the Field Code conceded that attorneys, even if considered private actors, could abuse the state power they were allowed to exercise when it stated “[w]e propose to ... place the law on its proper footing, of indemnity to the party, whom an unjust adversary has forced into litigation … The losing party, ought … as a general rule, to pay the expense of the litigation. He has caused a loss to his adversary, unjustly, and should indemnify him for it.” The report’s support for a “loser-pays” provision demonstrates that the legal system continued to be understood as prone to abuse by those triggering state power against the innocent victims of lawsuits. The Field Code supported both unregulated attorneys’ fees and a loser-pays rule that would apply to both plaintiffs and defendants.

But while legislatures across the country tended to go along with the part of the report that recommended attorneys be able to arrange their payments with clients however they wanted, the “loser pays” part of the report’s recommendations went largely by the wayside, and, where it was adopted, it tended to be adopted to the benefit of plaintiffs only, and federal law soon came to reflect that trend:

Three federal statutes -- voting rights legislation in 1870, the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, and the Sherman Act of 1890 -- allowed successful plaintiffs, but not successful defendants, to recover their legal expenses. Various state laws followed suit. The one-way attorneys’ fees shifting statutes were in the fashion of the Progressive Era, namely tools to encourage attorneys to file lawsuits on behalf of poorer plaintiffs against certain large corporations. At first, legislation that made corporations alone pay the costs of litigation regarding successful claims against them for the payment of labor rendered, overcharges, or the injury of livestock, was struck down by the Supreme Court as a violation of the Equal Protection Clause. However, when such legislation was amended to make “any person or corporation” liable for successful plaintiff’s costs of litigation for the same class of claims, it was sustained as a “police regulation designed to promote the prompt payment of small claims.” By the 1960’s, nearly all major civil rights and environmental statutes included one-way fee-shifting provisions. Other statutes brought whole areas of litigation under the one-way fee-shifting rule. By the 1980’s, the Supreme Court went even further by reading one-way fee-shifting statutes broadly and encouraging enforcement under such statutes in a way that tended to grant fees to prevailing plaintiffs while denying them to prevailing defendants. The result today is that, while one-way fee shifting rules govern in fields of litigation in which the plaintiff tends to sue for injunctive rather than monetary relief, the field of personal injury in tort for money damages is left unregulated by either limits on attorneys’ fees or a “loser-pays” rule. An explanation as to why may lie in the fact that, over the years, the number of attorneys has risen dramatically, and with it the power of those pressing for a regime expanding the demand for lawyers and opposing any proposals for rules that might tend to reduce that demand … As the number of lawyers rose, so did the need to create additional demand for lawyers, and one-way, pro-plaintiff fee-shifting statutes and a system of unregulated attorneys’ fees did just that.

This coercive pressure to pay lawyers to settle frivolous cases pervades the litigation system. For example, as law professors have pointed out back in 2005, “Because it costs employers (1) between $4000 and $10,000 to defend an EEOC charge, (2) at least $75,000 to take a case to summary judgment, and (3) at least $125,000 and possibly over $500,000 to defend a case at trial, it almost always makes good business sense to settle a case for $4000.”

As a result of dynamics like that, there has been a decreasing rate of jury and bench trials, and an increase in settlements.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll explore the influence of lawyers in America today.

Paul, Enjoying this series. This particular point has always bothered me but I am not an expert. You are and you have confirmed my worst fears. Anything to be done about this? I have sent it to all my lawyer friends...