As Fernanda Pirie writes in her book The Rule of Laws: A 4,000-Year Quest to Order the World:

The national legal systems now found throughout the world are almost all modeled on those developed by European nations in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. During two hundred years of colonial rule, they exported and imposed their laws throughout the world and promoted a new international order of clearly demarcated states. Today, the leaders who take their seats at the United Nations are expected to maintain their own systems of laws and courts, as well as upholding democracy, human rights, and the rule of law. But within the long history of human civilizations, the rise and dominance of the state and systems of national law form just the latest chapter. The Europeans displaced legal systems that were already ancient when da Gama arrived in India, and even the Romans were inspired by earlier precedents. There is nothing inevitable about the shape that most legal systems take around the world today … The rule of law has a history, and we need to understand that history if we are to appreciate what law is, what it does, and how it can rule our world for better, as well as for worse.

Pirie writes that early Western law focused on separating the pure from the unpure, however clumsily:

The Pentateuch (or Torah), the first five books of the Bible, probably took the form we know today between the ninth and fifth centuries BCE. They describe how, after leading his people to safety, Moses gave them laws for worship, ritual, and sacrifice, along with an extremely complicated set of dietary rules … This larger purpose of the Israelites’ laws sheds light on their distinctions between clean and unclean. The cattle, sheep, and goats that provided basic sustenance in the region were cloven-hoofed ungulates who chewed the cud, so the priests decided that these qualities should define the class of clean animals. As a result, it included some wild beasts, such as antelopes and wild goats, but not all domestic animals, most importantly pigs. They declared that fish without scales and fins were abominations, as were four-footed creatures that could fly, animals with hands that used them for walking, and anything that swarmed. To their minds, proper animals should walk, fish should swim, and birds should fly. Hopping was close enough to walking, so they declared that grasshoppers, crickets, and some locusts were clean. But swarming was not. Whatever the rationale behind their decisions, the rules were more important for what they symbolized, dividing pure from impure, than for the ways in which they might save Jews from unclean food.

But Pirie points out that the law is often clumsy, especially when it is hastily made to respond to the latest real (or imagined) crisis:

Even contemporary laws formulated in response to a social problem are not always as pragmatic as our governments would have us believe. When a tragedy occurs involving handguns or dangerous dogs, or the media gets overexcited about criminals evading justice, politicians rush to legislate. But all too often the new laws are impractical or unenforceable. The problem of hate speech was the subject of legislation in the United Kingdom which many commentators thought could barely, if ever, be enforced. But governments must be seen to be doing something. Passing a law gives their citizens the impression that politicians are in control of the situation. And, to be less cynical, it also expresses the moral revulsion of society at large. The laws set out, for all to see, the moral parameters of the civilized society our rulers claim they can create.

Pirie writes that laws can empower people as well as control them:

Laws provide tools with which rulers can order and control their societies. But they also offer resources to which people can turn as they seek justice and resist the arbitrary exercise of power. When laws are written out, different people can read and refer to them. The Chinese rulers created laws as practical tools of government, but when scribes placed them onto long bamboo strips, which they pinned up on gateposts and at markets, ordinary people could quote the rules to argue about an abuse of power or appeal against an unfair sentence, to the discomfort of local officials … This is why the apparently simple technique of lawmaking can give powerful arguments to ordinary people … And once made explicit, written on palm leaves or inscribed on clay tablets, laws become objective. They can be tools to exercise power, means to legitimate it, and resources for those who would resist it. Once these laws were recorded and made public, people could appeal to them for justice. The determined dictator might tear up the rule book, but he could not do it unnoticed.

In ancient Mesopotamia:

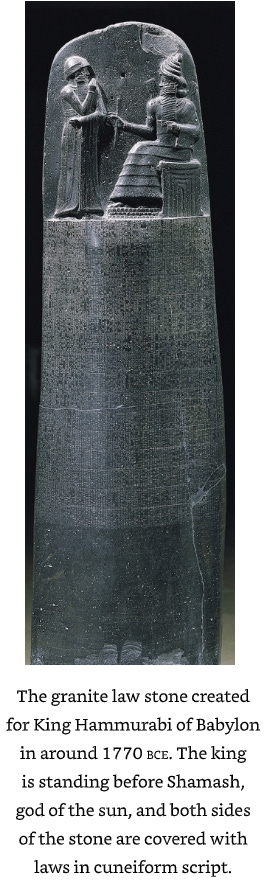

By making laws, Ur-Namma [founder of the Third Dynasty of Ur, who ruled from 2112 BC – 2094 BC] was promising that anyone wrongly imprisoned, or thrown into debt bondage, should get relief. He was trying to put Ur society on a new footing. By publicizing his laws for all to see, he made it easier for people to hold his officials to account. Anyone could now quote a law, which had been pronounced by the king. It was the beginning, indeed, of the rule of law … [A few hundred years later] Hammurabi [in the Old Babylonian Empire] ordered that his laws be inscribed onto tall stones and erected around his territories, where they could be seen and read out to anyone. On the grandest of these, a great granite slab, his stonemasons carved a picture of the king standing before the god of the sun, Shamash, obviously receiving divine authority. Beneath, the slab is covered by delicate cuneiform marks, which make up almost three hundred laws. Hammurabi’s legal text concludes with a long epilogue in which the king makes grand promises for the effects of his laws: “These are the judicial decisions that Hammurabi, the king, has established to bring about truth and a just order in his land … Let any wronged man who has a lawsuit come before my image, as king of justice, and have what is written on my stele read to him, so that he may understand my precious commands; and let my stele demonstrate his position, so that he may understand his case and calm his heart … I am Hammurabi, king of justice, to whom Shamash has granted the truth.” … It was the people who needed laws as resources for justice, standards that they could quote against anyone who might try to oppress them—and this was what Hammurabi claimed he was giving them. In the lengthy epilogue to his laws, the king described the terrible curses and misfortunes that would be heaped upon the head of any future ruler who failed to respect the justice of his laws. Line after line invoked the gods to punish such a person: to ‘break his sceptre’, ‘curse his destiny’, ‘destroy his land by famine and want’, ‘shatter his weapons’, and ‘strike down his warriors’. Hammurabi was telling the world at large not just that he was an important ruler who enjoyed the favour of the gods, but that his laws would ensure justice into the future. This was the rule of law.

Then came the Roman Empire:

The [Roman] consuls … agreed that the Twelve Tables should be inscribed onto bronze tablets and nailed up in the Forum, the public centre of the town. Although few citizens were literate, simply by being written out and prominently displayed the laws signalled the fact that all Roman citizens had the right to refer to their laws … [T]he summoning of assemblies confirmed the important fact that government decisions had to be debated and confirmed by the citizens at large … The provisions of the Twelve Tables were rather sparse. But, like Hammurabi’s laws, they set out general principles that could be applied to a range of cases. They stated, for example, that someone who killed a thief in his house in the middle of the night had a defence to a charge of homicide. The implication was that someone who surprised a thief during the day was supposed to show more restraint. The laws also set out a complicated process that creditors needed to follow before they could impose debt bondage, which probably did give a measure of protection to debtors, at least those educated and confident enough to quote the laws. And they established technical requirements for marriage and inheritance. The assemblies passed several further laws to regulate contracts and guarantees, the status of minors and illegitimate children, and inheritance and succession practices, which were a constant source of problems. Even if ordinary citizens avoided the more complex legal procedures, the principles behind these laws surely made their way into the thinking of people who mediated local disputes. Rome was a small place, and the most important laws would have been known to all.

Roman magistrates, called praetors, began the practice of formalizing the mode of legal claims:

During the second century BCE, the urban praetors, those concerned with the affairs of Roman citizens, assumed the task of supervising the civil courts. And these officials, although not legally trained, became hugely influential in the development and expansion of Roman law. As the city grew and the affairs of its citizens became more complex, the judges, or iudices, began to require that applicants use a specific form of words, a formula, to begin a legal case, in place of the complicated legis actiones the pontiffs had stipulated. The urban praetors now decided which formulae could be used in which cases, effectively determining what an applicant had to prove in order to succeed in his claim. Like other government officials, each praetor would issue an edict at the beginning of his year in office setting out how he would fulfil his duties. On a large whitewashed board, he would write out, in red letters, the laws and orders he considered to be most relevant for Roman citizens, as well as the formulae they should use. This board was set up in the Forum for all to see. In this way, the praetors could deliberately develop Roman civil law, formulating new and innovative legal actions. Now, a Roman citizen with a legal problem would approach the urban praetor, who would decide whether to make an immediate order. He could grant an interdict, an injunction to forbid the use of force, for example, or make orders about burials, water rights, or other urgent matters. If he thought the case had been properly formulated, he would then send it to a judge for a decision. Both praetors and judges heard cases on a wooden platform in the Forum, where they sat in the shade of the surrounding temples. Litigants, or their advocates, would address them from the ground, where they might attract a circle of interested onlookers. Both the litigants and their advocates were expected to wear togas, rather than more informal daily wear, and to speak in proper Latin. As Cicero later explained, the advocates were supposed to avoid displaying anger or partiality, should not vomit from drunkenness, and should not allow themselves to be smothered in kisses by ardent admirers.

The Romans developed a system to prevent bribery by requiring praetors to announce their edicts prior to taking office:

[T]he tribune Cornelius proposed a new law in 67 BCE requiring each new praetor to announce his edict in advance of taking office, and then to abide by its laws. Many of the senators who might have benefitted from the cosy corruption of a man like Verres opposed the law, but the tribune persisted and the law was passed. This effectively restricted the opportunities for bribery and corruption while also making the application of the law more predictable.

But soon the law became too complex to be absorbed by the citizenry, and elites came to take over the law’s development:

[T]he Twelve Tables still loomed large in the collective Roman imagination. The original bronze tablets had come to seem foundational to the establishment of their city and the freedoms of its citizens, representing an end to tyranny. Schoolboys had to memorize them and learned that their rules provided the basis of their rights … But in the hands of the praetors, the law was changing too fast for this idea to be maintained. By the middle of the first century bce the laws of the Twelve Tables had come to have more moral than legal authority, and eventually they were dropped from the school curriculum. Those who staffed and used the courts now faced the problems of complexity and corruption. The praetors were not legal experts, but rather, ambitious men en route to higher political office … Complexity and obscurity are recurrent problems in developed legal systems. Roman law had begun as an essentially practical system. The laws of the Twelve Tables, the legislation passed by the assemblies, and the formulae specified by the praetors were all created with contemporary problems in mind; they were designed to regulate the lives of Roman citizens and served as the basis for argument and decision-making during trials. They were resources for those who needed to fight legal cases. They also, from a very early period, symbolized the rights of all citizens to a measure of equality before the law. But in the hands of the jurists, law became an academic exercise. Learned men conducted debates in the rarefied surroundings of their aristocratic mansions, where they were free to develop their intellectual interests. Roman law had become an elite pursuit, insulated from the social and political pressures of Roman life as it unfolded in all its complexity outside their walls.

Although the over-extended Roman Empire fell, the example of its legal system survived:

When the Roman armies withdrew from northern Europe in the fifth century of the common era, they took with them their systems of government and their laws. Gallic, Celtic, and Anglo-Saxon tribesmen had little use for complex sets of legal rules … Still, they were impressed by the grandeur of the Roman emperors and decided to create their own legal codes. Eventually, their assorted rules, customs, and ideas developed into the sophisticated European systems that came to dominate the world. But it was centuries before they produced anything like a coherent body of law.

In Europe:

[The Roman Emperor] Theodosius II ordered a compilation of laws to form the code that bears his name, which was completed in 438 … Aetius [a Roman general in the late Roman Empire] ordered the compilation of a set of laws for the Bretons, whom he had recently subdued, and probably another for the Franks. But these initiatives were very different from the previous practice of extending Roman law to all new citizens. They were new sets of laws, formulated specifically for the barbarians. The Breton laws, according to surviving reports, forbade vengeance, specified compensation payments, regulated relations between the military and civilians, and criminalized tax fraud, homicide, adultery, theft, and illegal grazing … [At around the same time, the Ostrogoth king in Italy, Theodoric the Great, was] [d]eclaring that people could still rely upon Roman laws [and] he gathered a collection of them into his Edictum Theodorici (Edict of Theodoric) for his judges and other officials. As he confirmed in a letter to the Genoese Jews, ‘the true mark of civilitas is the observance of law. It is this … which separates men from beasts’. Law remained an important marker of civilization, even competition, among the new rulers.

Law came to stand for a way that rulers could avoid bias and thereby maintain their legitimacy. As Pirie writes:

In a decree of 802, Charlemagne also demanded that his judges base their judgements on the written law, rather than on their personal opinions … Why did Charlemagne and his successors, the Carolingian kings, think it worthwhile to put all this time and so many resources into lawmaking? After successful campaigns against the Visigoths and Burgundians in 774, Charlemagne moved on to Italy and deposed the Lombard kings. He was then able to negotiate with Pope Leo III to recognize him as emperor. Disillusioned with imperial plots in the east and concerned about attempts on his own life, the pope crowned Charlemagne Roman emperor in 800. Now Charlemagne needed to adopt an appearance of imperial dignity. He did not have the administrative apparatus to reproduce Roman systems of government, with its Senate, officials, judges, and courts, but he could make laws. The Lex Salica might have started as a list of penalties and tribal customs, but a Latin text could be presented as something grander, the work of an authoritative king. It demonstrated that the ruler was governing properly, as the Roman emperors had done before him. Lawmaking, as one scholar has put it, was an exercise in image-building.

With more and more law, and more disputes for the law to settle, judges came to prominence, such that in England, the collection of decisions handed down by judges came to be know as the “common law,” which, although not embodied in a statute, had the force of law:

[I]n the late twelfth century a young scholar produced a treatise on ‘the laws and customs of the kingdom of England’ which he named after his patron, the judge Ranulf de Glanvill. Clearly inspired by Justinian’s Corpus Iuris, he intended that his work would explain the practices of the English royal courts to those who were more familiar with the civil law. He declared that he was describing the ‘English law’, which, although not written, was, as he explained, the law applied in the kings’ courts. He insisted that the English common law constituted a system of its own … There was a strong sense that the English common law was based on ancient custom, and when the barons wanted to challenge the power of King John, they felt entitled to create a legal document to limit his powers, the Magna Carta … The kings could nevertheless issue decrees to supplement the courts’ practices. Major pieces of legislation, such as the Magna Carta, introduced legal reforms in all sorts of areas. In addition to the famous clauses that limited the powers of the Crown, the Magna Carta dealt with wardship and dowry, the regulation of moneylenders, weights and measures, and the management of royal forests, also setting out rules for foreign merchants, mercenaries, and hostages as well as numerous procedural measures designed to improve court processes. Some of these effectively gave people new rights—for example, in the case of unlawful dispossession of land. But for the most part, it was the judges of the kings’ courts who developed the common law. Over the following centuries, they became more specialist, developing and refining the system of writs and gradually extending their jurisdiction to cases traditionally heard by local courts.

There soon developed a corps of legal advocates who studied the procedures and decisions of the courts so they could better advocate for their clients:

[A]dvocates learned about the law through practice and apprenticeship. Initially, they gathered at the court of the Common Bench at Westminster, where they listened to cases, kept notes on the most interesting ones, studied statutes, and probably engaged in advocacy exercises. From around the 1340s, they began to move into the apartments of the Knights Templar on what is now Fleet Street, and they soon expanded into other inns in the area, conveniently close to the kings’ courts. Before long they had established a society of expert lawyers, and eventually the new institutions introduced training programmes for aspiring advocates. At the same time, the judges began to consult and refer to records of previous cases. Gradually, they coordinated their approaches to legal problems, and their practices of consulting past cases eventually led to the system of precedent … [I]n the precedents and procedures used by English advocates and the institutions in which they trained, the English common law followed a different path, and it remained distinct. When the movement for codification swept continental Europe in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it had few influential advocates in England. Here the judges and lawyers continued to develop their own laws, relying on past cases … Over time, English law developed, rather as Roman law had, from a combination of writs, decrees, and recorded cases.

As the Church came to own more property, clergymen became involved with more disputes to be resolved, and the threat of excommunication was used to enforce settlements:

Records from Septimania, in the south of France, indicate that in the twelfth century most people sought out ‘good men’, that is, arbitrators, to help with their disputes. In serious cases, generally those involving large landholdings, the parties might turn to the abbot of the nearest monastery or the local viscount to mediate. Monasteries were now substantial landowners, with complicated rights to rents and other dues, and their abbots would often find themselves in dispute with the local nobility about their land rights and entitlements. Cases could drag on for years as different prelates and nobles tried to mediate between them. The arbiters might apply pressure to the parties, but they could not force them to accept a decision, or even to abide by the terms of a compromise. Occasionally they could refer to a charter, which might indicate who had legal rights, but the precise Roman categories of land ownership had largely been forgotten, and without them it was difficult to hand down an authoritative judgement. More often they simply compromised by dividing up the property in dispute. Even when they negotiated an agreement, mediators had to ask the parties to swear an oath to abide by its terms. They were dealing with sentiments of honour and shame, particularly among members of the upper classes, whose pride had to be soothed. The arbiters persuaded them to compromise by referring to respected wisdom and threatening public condemnation. Gradually things changed. During the thirteenth century, the French kings began to assert more authority over the provinces that they nominally controlled, sending agents to collect rents and demand service from landowners … [Kings] could call on papal delegates to threaten a citizen who refused to accept a judge’s order with excommunication.

Kings began to create a system of legal appeals where final decisions were made closer to the king’s center of power, and a uniform language of law spread nationwide:

The French kings also drew the nobility into the circles around them. Keen to establish a more centralized judicial structure, they instituted a system of appeals to new courts in Paris. Now a landowner in Septimania might find that a nobleman was making a claim to his farms in a court hundreds of miles away, or that he faced demands for military service by the agents of a distant government. Gradually, the pressure to compromise within a close social circle disappeared and the arbiters started to act like judges, making definite decisions, which they expected the parties to obey. At the same time, they began to record the decisions they made in their new courts more systematically, using Roman words and phrases, indicating that they had ‘inquired about the truth’ and used ‘witnesses and instruments’. Whether or not they actually had, these phrases created a sense that there was a proper way of meting out justice, one that resembled the legalistic practices of the Roman civil law … As the judges and mediators tried to apply consistent rules in their courts and people accepted authoritative decisions, the old systems of mediation and compromise began to break down at all levels. The new laws provided people of all ranks with a machinery that was impersonal, but which also offered them a language by which to challenge others, even those of higher status. In the courts, city consuls found they could resist the claims of a viscount, the viscount could respond to the arguments of an archbishop, the archbishop could take on the consuls, and all of them could stand up to the king. They could cite the law in arguments against people who were both distant and more powerful. It was not, of course, a perfect system, and the legal arguments did not always work, but they gave people a way to take on those who tried to dominate them. Law now supplemented the moral and religious arguments people had always used in front of arbitrators, and its ideas and techniques filtered into local contexts. The lords imitated the king and hired trained lawyers to be their judges, while both villagers and city dwellers discovered that the new courts were places where they could assert some rights … The legal reforms introduced by Henry II in the late twelfth century put the power to declare what the ‘common law’ was in the hands of the judiciary. Royal judges travelled around the country to hold eyres, courts in which they adjudicated on disputes among landowners, generally arguments over property and succession, and it became an insult to the king to compromise after a writ had been issued. They also sat in judgement on those accused of serious crimes, rather than allowing vengeance to run its course. Meanwhile, English scholars, inspired by the example of Rome, wrote treatises on the ‘unwritten law’ of England. Their texts marked the beginnings of the legal system that eventually extended throughout England and Wales, but it was several hundred years before this system superseded local and specialized laws and courts … [F]or most of the Middle Ages and into the early modern period peasants, artisans, churchmen, and merchants all turned to local courts, which were often sanctioned by the Crown to resolve disputes. They cited custom as well as law to local judges and expected a jury of their peers to consider charges against them … [T]he population was rapidly increasing, practically doubling between 1520 and 1600. The king introduced many new laws and statutory offences, and litigation increased, reaching staggering levels under Elizabeth around the turn of the century. One notorious local bully in Shrewsbury brought sixteen actions against his neighbours in the course of a year.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll explore how the law developed to pass responsibility for deciding cases down to juries.