Having explored in the previous essay series the problem of the federal over-regulation of citizens (a problem driven in part by judges’ institutional interest in embracing legal complexity), in this essay we’ll consider the question as to whether and how federal judges might be regulated themselves. Years ago, I wrote a law review exploring the fascinating history of the Founders’ understanding of the ways in which the Constitution allows for the regulation of the federal judiciary by Congress. That article was published in the Pepperdine Law Review and entitled “Congress's Power to Regulate the Federal Judiciary: What the Congress's Power to Regulate the Federal Judiciary: What the First Congress and the First Federal Courts Can Teach Today's Congress and Courts,” and it can be found here. This essay will draw mainly from that article’s introduction and conclusion.

I began the article by recounting an experience I had while serving as the Chief Counsel of the House Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on the Constitution. The Congressional Research Service (“CRS”) is part of the legislative branch of the federal government. It is a department of the Library of Congress that works exclusively as a nonpartisan analytical, research, and reference arm for the United States House of Representatives and Senate, and its mission is to support an informed national legislature. In July 2004, in the midst of House debate over a bill that would restrict federal court jurisdiction, CRS issued a memorandum stating its staff was unaware of any precedent for a law that would deny the inferior federal courts original jurisdiction or the Supreme Court appellate jurisdiction to review the constitutionality of a law of Congress. However, the next month, in response to a letter from the House Judiciary Committee, CRS admitted its previous memorandum was in error, stating, “This memorandum responds to your request that we reassess an earlier memorandum of ours ... [§ 25 of the Judiciary Act of 1789] did operate to preclude any Federal court from deciding the validity of a Federal statute from 1789 to 1875. Accordingly, our earlier memorandum was incorrect.” That the official research arm of Congress missed such an important precedent in the history of Congress's power over the federal courts--the Judiciary Act of 1789, enacted during the First Congress--demonstrates how, in current times, it is all too easy to forget the vital origins of the federal judiciary and how those origins inform a historically accurate understanding of Congress's authority to limit federal court jurisdiction.

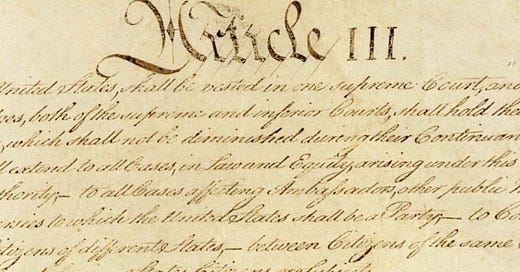

The members of the Constitutional Convention that drafted the Constitution, including those who were elected to serve in the First Congress, had a much more robust view of Congress's powers over the federal courts than prevails today. The modern Supreme and lower federal courts' involvement in virtually every detail of national policy has resulted in the common presumption that such a situation is constitutionally required. Yet the Constitution, in Article III, Section 2, clause 2, provides that the lower federal courts are entirely creatures of Congress, as is the appellate jurisdiction of the Supreme Court, excluding only cases within the Supreme Court's original jurisdiction -- those “affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party.” By the terms of the Constitution, then, it is up to Congress to decide whether and how to grant any of the federal courts jurisdiction to decide cases, including those involving constitutional issues. The sole exception is that the Constitution requires the Supreme Court to hear cases within its very limited original jurisdiction (which includes only cases involving ambassadors and other high-ranking ministers and cases in which states are parties).

That was also the understanding of the First Congress, as demonstrated by its enactment of the Judiciary Act of 1789, which provided that the Supreme Court, regarding constitutional challenges to federal law, could review only those final decisions of the state courts that held “against [the] validity” of a federal statute or treaty. Under the Judiciary Act of 1789, if the highest state court held a federal law constitutional, no appeal was allowed to any federal court, including the Supreme Court.

Not only did the Act limit federal court jurisdiction, but it did so in a way that was specifically designed by Congress to affect a specific result, namely the increased chance that federal laws would be upheld. If the highest state court upheld a federal provision, there could be no appeal to federal court, and the decision upholding the federal provision would stand. For the first 125 years of our nation's existence, the only state court judgments reviewable in the Supreme Court or by any federal court absent diversity jurisdiction were those in which the highest state courts had denied federal claims or defenses. Under the Judiciary Act of 1789, a denial of a federal claim or defense by the highest state court would result in another opportunity for federal courts to reverse such state court decisions and uphold the federal claims or defenses. On the other hand, if the highest state court upheld a federal claim or defense, that was the end of the matter, and no federal court would have the opportunity to hold otherwise and deny such federal claims or defenses.

The Judiciary Act of 1789 significantly restricted the range of issues that could be decided by the newly-created federal courts and the Supreme Court in other ways as well, leaving a huge variety of cases involving constitutional, tort, and contract issues beyond the reach of any federal court.

The principal drafter of the Judiciary Act of 1789 was Senator Oliver Ellsworth of Connecticut, a greatly influential founder who had served as one of five members of the Committee of Detail that issued the first draft of the Constitution and who would later serve as the third Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. As Ellsworth wrote when he served on the Court, the federal courts under the Judiciary Act of 1789 had “cognizance, not of cases generally, but only of a few specially circumstanced, amounting to a small proportion of the cases which an unlimited jurisdiction would embrace.” Senator Ellsworth was also the principal drafter of two other statutes enacted in the First Congress: legislation that required certain process and procedures to be used by the federal courts, including the Supreme Court; and legislation defining federal crimes to include a provision that would immediately remove a federal judge from office through means independent of impeachment, namely conviction of bribery in federal court.

Like the Judiciary Act of 1789, the Process Act of 1789 and the Crimes Act of 1790, having been passed by the First Congress, are perhaps the statutes most informative of an original understanding of Congress's constitutional power over the federal judiciary. As has been observed by the authors of the leading treatise on federal court jurisdiction, Richard Fallon, Daniel Meltzer, and David Shapiro’s Hart & Wechsler's The Federal Courts and the Federal System 28 (4th ed. 1996), “the first Judiciary Act is widely viewed as an indicator of the original understanding of Article III and, in particular, of Congress' constitutional obligations concerning the vesting of federal jurisdiction.” And as the Supreme Court itself has recognized, in Wisconsin v. Pelican Ins. Co., 127 U.S. 265, 297 (1888), the Judiciary Act of 1789 was “passed by the first Congress assembled under the Constitution, many of whose members had taken part in framing that instrument, and is contemporaneous and weighty evidence of its true meaning.”

More recently, the Supreme Court has declared itself the “ultimate interpreter of the Constitution,” Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186, 211 (1962), which implies that it -- and not Congress -- is also the ultimate arbiter of the powers of Congress over the Supreme Court's jurisdiction. If that is true, then the Court alone is the master of its own domain. The Supreme Court has also stated, albeit in dicta, in United States ex rel. Toth v. Quarles, 350 U.S. 11, 16 (1955), that Article III courts are “presided over by judges appointed for life, subject only to removal by impeachment.” However, both statements, in many ways, are placed in doubt by the enactments of the First Congress and the actions of the former members of the Constitutional Convention who served in the First Congress.

Indeed, it may be striking to the modern reader that the First Congress enacted statutes severely limiting the jurisdiction of the federal courts. It did so in a way that favored upholding federal laws, that gave Congress complete control over procedure in federal courts, and that provided a means by which federal judges could remove other federal judges independent of the process of impeachment. But that is all less surprising when one understands that the Founders, and some of the most prominent American leaders who followed them, did not view the federal courts as the most legitimate means of correcting constitutional errors.

James Madison saw popular elections, not judicial review, as the most legitimate means of correcting constitutional errors. Madison wrote in Federalist Paper No. 49,that constitutional disputes could not ultimately be resolved “without an appeal to the people themselves, who, as the grantors of the commission, can alone declare its true meaning, and enforce its observance.” Madison also wrote in Federalist No. 51 that “[a] dependence on the people is, no doubt, the primary control on the government.” In a letter to Spencer Roane (May 6, 1821), Madison responded to the question “what is to controul Congress” when it exceeds its constitutional authority with the answer: “Nothing within the pale of the Constitution but sound argument & conciliatory expostulations addressed both to Congress & to their Constituents.” And Madison, in a December 19, 1791 piece in the National Gazette, observed that among the most important devices for securing the sovereignty of the People, matched only by “a circulation of newspapers through the entire body of the people,” was “Representatives going from, and returning among every part of them.”

In a letter from Thomas Jefferson to Charles Hammond (August 18, 1821), Jefferson lamented that:

the germ of dissolution of our federal government is in the constitution of the federal judiciary; an irresponsible body, (for impeachment is scarcely a scare-crow,) working like gravity by night and by day, gaining a little to-day and a little to-morrow, and advancing its noiseless step like a thief, over the field of jurisdiction, until all shall be usurped ...

Responding to the argument that federal judges are the final interpreters of the Constitution, Jefferson wrote in a letter to William Jarvis in 1820:

You seem to consider the [federal] judges as the ultimate arbiters of all constitutional questions; a very dangerous doctrine indeed, and one that would place us under the despotism of an oligarchy. Our judges are as honest as other men are and no more so. They have with others the same passions for party, for power, and the privilege of their corps … [T]heir power is more dangerous as they are in office for life, and not responsible, as the other functionaries are, to the elective control.

In a letter to Judge Spencer Roane (September 6, 1819), Jefferson strongly denounced the notion that the federal judiciary should always have the final say on constitutional issues:

If [such] opinion be sound, then indeed is our Constitution a complete felo de se [act of suicide]. For intending to establish three departments, co-ordinate and independent, that they might check and balance one another, it has given, according to this opinion, to one of them alone, the right to prescribe rules for the government of the others, and to that one too, which is unelected by, and independent of the nation ... The constitution, on this hypothesis, is a mere thing of wax in the hands of the judiciary, which they may twist and shape into any form they please.

And as early as 1823, in a letter Monsieur Coray (October 31, 1823), Jefferson observed:

At the establishment of our constitutions, the judiciary bodies were supposed to be the most helpless and harmless members of the government. Experience, however, soon showed in what way they were to become the most dangerous; that the insufficiency of the means for their removal gave them a freehold and irresponsibility in office; that their decisions, seeming to concern individual suitors only, pass silent and unheeded by the public at large; that these decisions, nevertheless, become law by precedent, sapping, by little and little, the foundations of the constitution, and working its change by construction, before any one has perceived that that invisible and helpless worm has been busily employed in consuming its substance. In truth, man is not made to be trusted for life, if secured against all liability to account.

Abraham Lincoln, in his First Inaugural Address (March 4, 1861), said:

[T]he candid citizen must confess that if the policy of the government, upon vital questions, affecting the whole people, is to be irrevocably fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court ... the people will have ceased, to be their own rulers, having, to that extent, practically resigned their government, into the hands of that eminent tribunal.

And more recently, Judge Learned Hand, in his 1958 book The Bill of Rights, rejected rule by nine Supreme Court “Platonic Guardians,” writing, “If we do need a third [legislative] chamber it should appear for what it is, and not as the interpreter of inscrutable principles.”

As Larry Kramer has written in his book The People Themselves, the Supreme Court was never intended to be the ultimate authority on constitutional issues, and only in recent decades has the notion that the Supreme Court is the final authority on constitutional issues taken hold in popular opinion. As Kramer describes it:

[The Founders'] Constitution remained, fundamentally, an act of popular will: the people's charter, made by the people … [I]t was “the people themselves” -- working through and responding to their agents in the government-- who were responsible for seeing that it was properly interpreted and implemented. The idea of turning this responsibility over to judges was simply unthinkable … This modern understanding [of judicial review] is ... of surprisingly recent vintage. It reflects neither the original conception of constitutionalism nor its course over most of American history … [It was the original understanding that] [n]o one of the branches [of government] was meant to be superior to any other, unless it were the legislature, and when it came to constitutional law, all were meant to be subordinate to the people ... [I]n a regime of popular constitutionalism it was not the judiciary's responsibility to enforce the constitution against the legislature. It was the people's responsibility: a responsibility they discharged mainly through elections … It was the legislature's delegated responsibility to decide whether a proposed law was constitutionally authorized, subject to oversight by the people.

Explaining why there is not any mention of judicial review in the Constitution, Kramer writes:

Judicial review was not the question before the [Constitutional] Convention. The question was how best to prevent the enactment of unwise and unconstitutional federal legislative measures. The answer was an executive veto. (And not just a veto, either. Additional checks on the risk of bad legislation included federalism, bicameralism, and the likelihood that “the best men in the Community would be comprised in the two branches of [Congress].”) Some delegates were afraid that the executive might be too weak, but a solid majority felt otherwise and were concerned not to involve judges in the lawmaking process. That settled, there was simply no need to say or do anything more … This is why courts and judicial review were so rarely featured during ratification: members of the Founding generation had a different paradigm in mind. The idea of depending on judges to stop a legislature that abused its power never even occurred to the vast majority of participants in the debates.

As Kramer has described modern history, however:

[A]s Warren Court activism crested in the mid-1960s, a new generation of liberal scholars discarded opposition to courts and turned the liberal tradition on its head by embracing a philosophy of broad judicial authority … [T]he main body of liberal intellectuals put aside misgivings about electoral accountability, frankly conceding that judicial review might be in tension with democracy while justifying any trade-off on the ground that courts could advance the more important cause of social justice.

In sum, the only cases the Constitution required any federal court to have jurisdiction over were those involving ambassadors and in which a state was a party. That Constitution was defended in the Federalist Papers on the grounds that the federal courts it allowed were “next to nothing,” and, in any case, according to Alexander Hamilton in Federalist Paper No. 81, the Constitution allowed Congress to remove any “inconveniences” the federal courts should present in order to “best answer the ends of public justice and security.”

The First Congress, whose expressed understanding of the Constitution should hold great weight, overwhelmingly enacted the Judiciary Act of 1789, which prohibited review in any federal court of state court decisions that upheld federal provisions, even when federal constitutional claims were raised, significantly restricting federal court jurisdiction in a way specifically designed to increase the chances federal statutes would be upheld. It also contained a significant amount in controversy limit on jurisdiction, and no general federal question jurisdiction, leaving a huge variety of cases involving, among others, constitutional, tort, and contract issues -- including those required to be heard under the Treaty of Paris that set terms for the end of the Revolutionary War -- beyond the reach of any federal court. The regime established by section 25 of the Judiciary Act was only replaced when Congress amended the Act in 1914 to allow Supreme Court review of state court decisions upholding federal provisions, and Congress did so then simply to produce yet another substantive result, namely the upholding of state workers compensation laws.

The Process Act of 1789, also enacted by the First Congress, dictated precisely what procedures would govern in federal courts, a power Congress was recognized as having under its legislative powers.

And the Crimes Act of 1790 provided for a means of allowing federal judges to remove other federal judges from office supplemental to and independent of the impeachment process. That independent removal process was entirely consistent with the hornbook understanding at the time: that life tenure subject to good behavior could be lost following convictions in court. It was also consistent with the views of the most prominent Founders, with the contemporaneous state laws requested to be reviewed by the drafters of the Act, with similar statutes enacted by the First Congress regarding the court removal of civil officers of the United States, and with the House of Representatives' decision to allow the removal of a territorial judge through court process in 1796 following allegations that the judge had abused his power.

Oliver Ellsworth, the driving force behind all three Acts and the man dubbed the “father of the national judiciary,” was one of only five members of the Committee of Detail who issued the first draft of the Constitution at the Constitutional Convention. He was later appointed by George Washington to be the third Chief Justice of the United States, in which capacity he supported Congress's broad powers over federal court jurisdiction, the same view he held during the ratification debates.

The restrictions the First Congress placed on the federal courts, and Congress's control over the federal judiciary generally, are entirely consistent with Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137 (1803). Marbury established the principle of judicial review and stands for the proposition that the Supreme Court is the final decision-maker for issues within its original jurisdiction or under its authority by express statutory grant. If a case does not fall within the jurisdiction of the federal courts because Congress has not granted the required jurisdiction, federal courts simply cannot hear the case. The author of Marbury, Chief Justice John Marshall, after he decided Marbury, himself dismissed cases, when Congress had not granted federal courts jurisdiction to hear them, under the Judiciary Act of 1789. Marbury stands for the relatively simple proposition that if the federal courts perceive Congress or the President as acting beyond their lawful authority, they may exercise their judicial power to decide the case in conformity with the Constitution and declare the statute or offending action unconstitutional. The other branches, of course, have counteracting powers as well. If the President believes Congress or the courts have overstepped their constitutional bounds, the President may use the veto power, or the pardon power, to counter them. And if Congress believes the Executive is exceeding its constitutional authority, Congress can use the power of the purse to deny funding to the executive branch so it cannot administer its unconstitutional actions.

But if this system is to maintain a popularly and constitutionally legitimate balance, it must contain an element in which, if Congress perceives the Supreme Court to be exceeding its own constitutional authority, Congress can use its legitimate powers to alter the jurisdiction of the federal courts to place limits on those courts, including the Supreme Court. Without such an element, the Supreme Court, alone among all parts of the federal system, would be completely unchecked by any other branch of the federal government. It alone would be the judge of its own constitutional powers, no matter how poorly reasoned its decisions and no matter how dire the impact of those decisions, because the writing of poorly reasoned opinions alone (under prevailing interpretations today) does not constitute an impeachable “high Crime [or] Misdemeanor[].” Additionally, the doctrine of judicial immunity, explored in a previous essay, provides judges with vast protection from lawsuits claiming their actions or inactions harmed the public health and safety. Such a system, constituting rule by as few as five Justices (a majority of a Court with nine members), may be tolerated today, but it is inconsistent with the balance struck by the Founders and observed by many generations thereafter. That inconsistency has been greatly aggravated by the modern Supreme Court's frequent abandonment of the formerly long-standing principle that even when the courts have jurisdiction to hear constitutional claims regarding federal statutes, the courts should not strike down statutes enacted by duly elected legislatures unless such statutes are unconstitutional beyond dispute. (Under that former consensus principle, only two federal statutes were struck down by the Supreme Court in the first 67 years of its existence, a far cry from the modern Court's string of controversial 5-4 decisions striking down legislation.)

If an increasing number of 5-4 decisions by the Supreme Court results in a firm consensus that such decisions are “political” -- in the sense that they result from sharp ideological disagreements regarding policy -- then Congress may, in such an extreme circumstance, and following the First Congress, wish to increasingly restrict that Court's and other federal courts' ability to replace Congress's own political judgments with the political judgments of unelected judges, and to limit the federal courts' anti-democratic influence.

So far in this essay series, we’ve explored how the rise of legal complexity has diminished personal freedom. But why is it best to allow people a large berth of personal freedom anyway? That will be the subject of the next essay in this series, on Nobel Prize-winning economist F.A. Hayek’s two widely influential books, The Constitution of Liberty and The Road to Serfdom.