The Rule of Law – Part 11

How an increase in federal law leads to a decrease in individual liberty.

In this essay, we’ll explore how an increase in federal law leads to a decrease in individual liberty, as explained by Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch in his book Over Ruled: The Human Toll of Too Much Law.

Whereas federal agencies run by unelected bureaucrats largely run the country today, our federal system of government was originally structured for the purpose of making new federal law difficult, in the sense that lots of consensus was required for a new law to be enacted. As Gorsuch explains:

[James] Madison’s study of history persuaded him that people are naturally ambitious and tend to seek power over not just their own lives but others’. That fact of human nature, he believed, meant that the only sure way to protect our individual rights and keep government “off the backs of people” was to pit ambition against ambition. To that end, the Constitution Madison helped draft divided governmental powers both vertically and horizontally. It did so vertically by leaving most lawmaking power in the hands of state and local authorities—those closest to the people (a division of power called federalism). To the central government in a remote capital, the Constitution afforded only certain limited and enumerated powers: the power over foreign affairs, for example, along with other matters of a distinctly national character. Within the central government, Madison proceeded to divide power horizontally among three branches (legislative, executive, and judicial). Even within those branches, he checked and balanced power still further, nowhere more notably than when it came to the business of making law. As our Constitution envisioned it, any new law would have to win approval from two separate houses of Congress, composed of elected representatives chosen by different constituencies for different terms. Even then, a new law would have to earn the president’s approval or sufficient congressional support to override a veto. Making new laws was supposed to be a difficult business. As Madison saw it, by requiring such a long and deliberative process, one so dependent on consensus, the Constitution would ensure that any new law—any new restriction on liberty—enjoys wide social acceptance, profits from an array of views during its consideration, and as a result proves more stable over time. The need for compromise inherent in the design also aimed to protect minorities by ensuring that their views and voices and votes couldn’t be ignored. All in all, Madison hoped that the Constitution’s arduous requirements would result in less law and more freedom—and at the same time yield laws that are wiser, more respected, and more apt to protect minority rights … For Madison, down any other path lay “calamitous” risks. In governments where lawmaking is easy, he wrote, laws can quickly become “so voluminous that they cannot be read, or so incoherent that they cannot be understood,” and they may “undergo such incessant changes that no man, who knows what the law is today, can guess what it will be tomorrow.” The “sagacious, the enterprising, and the moneyed few” may be able to anticipate, influence, and even profit from so much shifting law. But the “industrious ... mass of the people” can do none of those things. In the end, law serves as an instrument only “for the few, not for the many,” sapping and ultimately destroying confidence in public institutions and law itself. Madison hoped differently for our new nation. He sought to ensure that Americans would live under the rule of law but not be crushed by law. Today everyone likes to throw around the phrase “rule of law,” but just what does it mean? Even political theorists debate the question. But there are a few important features that nearly everyone can agree on.

As Gorsuch writes:

The rule of law … requires laws that are publicly declared, knowable to ordinary people, and stable. So, for example, new legislation generally cannot be applied retroactively to past conduct you cannot alter but only to future behavior you can control … In an effort to capture the spirit of the rule of law, the Oxford University philosopher Joseph Raz once called it a set of principles designed to “constrain the way government actions change and apply the law—to make sure, among other things, that they maintain stability and predictability, and thus enable individuals to find their way and to live well.” Note that last condition. The rule of law is not an end unto itself. In large measure, it is about protecting individual liberty. “Observance of the rule of law,” as Raz said, “is necessary if the law is to respect human dignity,” a respect that “entails treating humans as persons capable of planning and plotting their future.” Or, to borrow from Hannah Arendt (who devoted much of her life to studying totalitarian regimes), the rule of law seeks to protect “man’s power to begin something new out of his own resources.”

But, mostly over just the last few decades, federal law has grown tremendously:

The fact is, much of the federal government’s expansion has taken place in just the last few decades. Between 1960 and 1979 alone, federal per capita domestic spending rose by 73 percent (adjusting for inflation). During the same period, civilian employment in the executive branch (excluding the Post Office and Department of Defense) rose by more than 50 percent. Today, some peg the civilian federal workforce at just under three million, almost all of whom work in the executive branch. But even that number fails to account for the swell of federal contractors, which by 2015 numbered over three million. The use of contractors has grown so much that some scholars call them a “shadow” federal workforce. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the numbers are so vast that, in 2018, one federal agency reportedly didn’t “have a clear understanding of how many contractors” it employed. Perhaps more surprisingly, according to one researcher, that same agency has used contractors to figure out whether it should use contractors … Here’s another way to think about the shift to Washington. Studies suggest that between 1969 and 2022, expenditures on lobbying the federal government increased from $40 million (in today’s dollars) to around $4 billion. Meanwhile, in 1969, 5 of the richest 25 counties and independent cities in the United States were located in the Washington, D.C., area; more recently, that number doubled to 10.

The federal government has grown largely unchecked because of its unique ability to print money for itself:

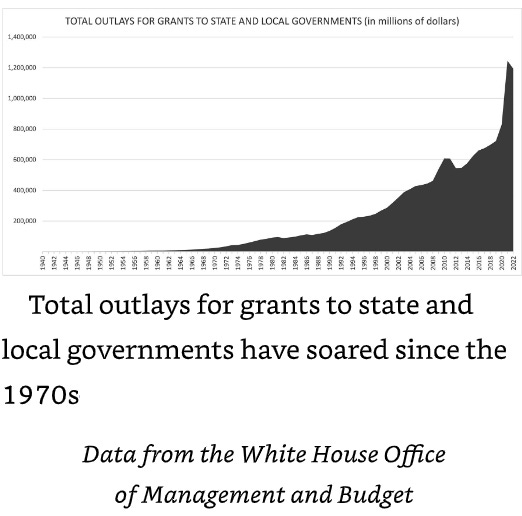

Not only has the federal government in relatively recent times assumed vast new responsibilities over matters once left to the states, it also has taken the reins in less direct ways. Unlike state and local governments, which operate with limited funds, the federal government enjoys the power to print money. And federal authorities have increasingly employed this power as a lever over state policy. Between 1960 and 2019, federal grants to states rose from $70 billion (adjusted for inflation) to over $700 billion—a 900 percent increase. Regularly, these grants come with strings attached that require states to enforce all manner of federal rules and standards. Overall, state governments now receive on average about a third of their revenue from the federal government—subject to Washington’s terms and conditions. Total outlays for grants to state and local governments have soared since the 1970s.

This growth of federal authority leads to individual citizens’ feelings of relative powerlessness. As Gorsuch writes:

[O]ur republican experiment faces danger when people feel isolated from their fellow citizens and unable to effect change in their daily lives … [W]hen decisions are made by a distant few rather than in institutions closer to the people and accessible to them. Cautionary signs stand before us. Open the newspaper on any given day and you may see headlines like “Why Does No One Vote in Local Elections?” or “In the U.S., Almost No One Votes in Local Elections.” Today, only about 27 percent of eligible voters participate in municipal elections, and “recent results suggest it’s slowly becoming even worse.” In 2021, New York City witnessed the lowest turnout in its mayoral election in nearly seven decades. A few years earlier, only about 27 percent of voters participated in Philadelphia’s mayoral election. Nor are these cities outliers. And “the numbers get even worse as you go down the ladder to county, school board and special elections.” A nonprofit foundation conducted a series of focus groups of millennials to explore the reasons for these developments. One common answer? “Many participants view[] local government as an afterthought at best.” It’s not just millennials, either. “Voters may just need more reason to care,” one article concluded, citing a poll of Los Angeles residents finding that “many would get more involved ... if they thought it would make any difference.” Meanwhile, more than 60 percent of respondents in a 2012 Pew Research Center poll stated that the federal government controls too much of daily life.

Since federal statutes are hard to enact by Congress due to constitutional requirements that involve consensus support among the House of Representatives, the Senate, and the President, federal law today runs mostly through the unelected bureaucrats who work at federal agencies and who can impose new law without having to work with the House or Senate. As Gorsuch writes:

In 2015, Congress adopted about one hundred laws. The same year, federal agencies issued 3,242 final rules and published another 2,285 proposed rules … Start with the agencies’ quasi-legislative powers … [T]hese [regulatory] rules are produced without effective presidential oversight. As Judge Neomi Rao, who once headed the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, has explained, “a single bureaucrat can at times exercise an authority that exceeds that of a member of Congress … Meaningful burdens can be imposed by regulations that do not reach the threshold for [this Office’s] review or even consideration by an agency head or other political official.” A report by the Pacific Legal Foundation found that 71 percent of the nearly 3,000 rules issued by the Department of Health and Human Services between 2001 and 2017 were issued by lower-level officials rather than Senate-confirmed agency leaders; at the Food and Drug Administration the figure was 98 percent. Hundreds of those regulations were deemed “significant” by the Office of Management and Budget, and, according to Senate testimony by one of the report’s authors, “the FDA’s own estimates found that the 23 most economically significant rules issued by non-Senate-confirmed employees have had a combined cost of $17.7 billion.”

The regulatory burden falls on companies and other organizations, but ultimately that burden falls on individual citizens:

Today, forest rangers operate with thick books of rules. Makers of ketchup, peanut butter, vodka—you name it—contend with rules that regulate down to the smallest detail. Ketchup must have a pH of 4.2 +/− 0.2 at certain stages of its formulation, and peanut butter may not have a fat content that exceeds 55 percent. Even the way the fat content is measured is closely regulated—it must be measured according to the rules “prescribed in Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists, 13th Ed. (1980).” But good news for vodka aficionados: officials recently amended rules that once required vodka to be “without distinctive character, aroma, taste, or color.”

This situation is the result of today’s judges and courts’ largely ignoring the original meaning of the words used in the Constitution that define federal powers. As Gorsuch writes:

In Article I of our Constitution, the People vested “All” federal “legislative Powers ... in a Congress.” A few decades after the postal route debate, Chief Justice John Marshall wrote for the Supreme Court that this assignment means “important subjects” must be “entirely regulated by the legislature itself,” while Congress may leave “details” (like postal routes) for other officials “to fill up.” For years, the Supreme Court described the principle that Congress “cannot delegate legislative power” to executive branch officials as “vital to the integrity and maintenance of the system of government ordained by the Constitution.” But it has been decades since our courts have done much to enforce that rule. And perhaps thanks in part to that omission, the pendulum has swung toward far-reaching delegations of legislative authority to agency officials. These days, Congress sometimes leaves agencies to write legally binding rules with little more guidance than “go forth and do good.” Laws tell agencies to regulate as “the public interest, convenience, or necessity” requires; others task them with setting “fair and equitable” prices; still others authorize agencies to determine “just and reasonable rate[s].” One law that made its way to the Supreme Court recently even leaves the nation’s chief prosecutor more or less free to decide for himself what kind of criminally enforceable registration requirements should apply to about half a million people. Thanks to broad delegations like these, agencies can write, change, and change again rules affecting millions of Americans—all without any input from Congress … If laws governing major facets of our society were once largely the work of elected representatives and the product of democratic compromises, nowadays they often represent only the current thinking of relatively insulated agency officials in a distant city.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll explore how federal agencies have become laws unto themselves.

Note: a concise video explaining the “Administrative State” in America can be found here.