The Implicitly Biased Implicit Bias Test

Government and private entities are promoting a false narrative of systemic oppression that itself creates a bias the same entities then use to "confirm" the false narrative.

The government of the City of Alexandria, Virginia, where I live, encourages people to take what’s called the “implicit bias test,” as do many other institutions. What is that test, and is the test itself implicitly biased?

Jesse Singal addresses this “test” in his book “The Quick Fix: Why Fad Psychology Can’t Cure Our Social Ills,” in which he writes:

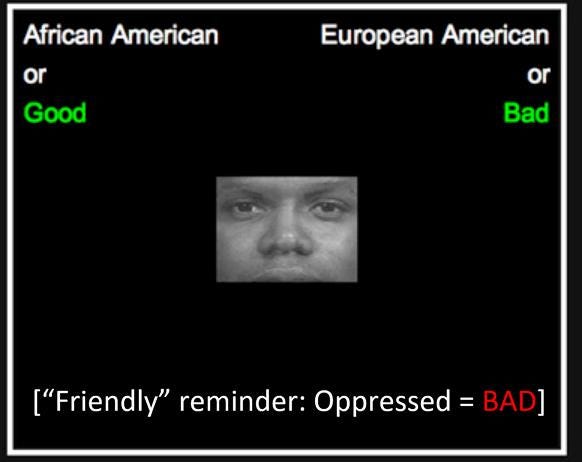

Implicit bias has enjoyed blockbuster success because there is a simple test that anyone can take to measure one’s own level of this affliction: the implicit association test, or IAT. If you’ve been in a diversity training anytime in the last few years, it’s likely you’ve come across this tool, which is promoted by Harvard University and a veritable army of well-credentialed social psychologists who study bias and discrimination. You can go to Harvard’s Project Implicit website at implicit.harvard.edu to take an IAT yourself, and if you do you’ll see that the setup is fairly simple. First, you’re instructed to hit i when you see a “good” term like “pleasant,” or to hit e when you see a “bad” one like “tragedy.” Then hit i when you see a black face, and hit e when you see a white one. Easy enough, but soon things get slightly more complex. Hit i when you see a good word or an image of a black person, and e when you see a bad word or an image of a white person. Then the categories flip to black/bad and white/good. As you peck away at the keyboard, the computer measures your reaction times, which it plugs into an algorithm. That algorithm, in turn, generates your score. If you were quicker to associate good words with white faces than good words with black faces, and/or slower to associate bad words with white faces than bad words with black ones, then the test will report that you have a slight, moderate, or strong “preference for white faces over black faces,” or some similar language.

But there’s a big problem with this test, namely:

[B]oth critics and proponents of the IAT now agree that the statistical evidence is simply too lacking for the test to be used to predict individual behavior. The proponents conceded this in 2015: The psychometric issues with race and ethnicity IATs, Greenwald, Banaji, and Nosek wrote in one of their responses to the Oswald team’s work, “render them problematic to use to classify persons as likely to engage in discrimination.” In that same paper, they noted that “attempts to diagnostically use such measures for individuals risk undesirably high rates of erroneous classifications.” In other words, you can’t use the IAT to tell individuals how likely they are to commit acts of implicit bias.

So even the originators of the implicit bias test now realize that even people with “bad” scores on the test are no more likely to actually engage in discriminatory behavior in real life (even though the whole point of the test is supposedly to indicate discriminatory tendencies). Regardless, the City of Alexandria and other entities still link to organizations that claim “You can find out your own biases by taking the implicit association test,” even when the main proponents of the test itself concede it’s “problematic to use [the test] to classify persons as likely to engage in discrimination” and “attempts to diagnostically use such measures for individuals risk undesirably high rates of erroneous classifications.”

Singal also points out that, ironically, people will tend to have worse scores on an implicit bias test and show bias against certain groups of people if they’ve been ingrained with the notion that those groups of people are inherent victims of things like “systemic racism.” As Singal writes:

There have always been alternative theories about what the IAT measures, though. In 2004, for example, Hal Arkes and Philip Tetlock published a paper that asked in its title “Would Jesse Jackson ‘Fail’ the Implicit Association Test?” In it, they argued that it could be the case that people who are more familiar with certain negative stereotypes score higher on the IAT, whether or not they unconsciously endorse those stereotypes. Along those same lines, some researchers have suggested that those who empathize with out-group members, and are therefore well aware of the unfair treatment and stereotypes they are victimized by, have an easier time forming the associations that the IAT interprets as implicit bias against those groups. In 2006, for example, Eric Luis Uhlmann, Victoria Brescoll, and Elizabeth Levy Paluck published the results of a very clever experiment they conducted on undergraduates in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. The participants were assigned to either “associate the novel group Noffians with words related to oppression and the novel group Fasites with words related to privilege,” or the reverse—Noffians privileged, Fasites oppressed. Then they were given a race IAT, but with Fasites and Noffians standing in for whites and blacks. As it turned out, “participants were faster to associate Noffians with ‘Bad’ after being conditioned to associate Noffians with oppression, victimization, and discrimination.” In other words, the experimenters were able to easily induce what the IAT would interpret as “implicit bias” against a nonexistent group simply by forming an association between that group and downtroddenness in general.

As the researchers positing the Noffians summarized their study:

Three studies explored the hypothesis that implicit measures of prejudice can tap negative, yet egalitarian associations. In Study 1, automatically associating African Americans with oppression predicted greater automatic prejudice. In Studies 2 and 3, classically conditioning associations between the novel group Noffians and words like oppressed, maltreated, and victimized led to greater automatic prejudice against Noffians. Results suggest that White Americans’ negative automatic associations with African Americans may partly result from associating members of low status groups with unfair circumstances.

What those studies found was that it seems any ready association of “black” with “bad” may simply reflect the fact that people have been ingrained with the thought that blacks are generally oppressed, and that association is what’s coloring their general assessment of where blacks stand on a binary spectrum of “good or bad.”

And so many governmental and private entities are promoting the false notion that the inevitable disparities in outcomes among people grouped by race are caused by “systemic racism,” and at the same time they’re promoting an implicit bias test that will tend to show that a test taker has an implicit bias against certain groups in part because they’ve been told that certain groups of people are victims of “systemic racism.”

That’s an implicitly biased merry-go-round. You might consider getting off.