Continuing this essay series on the human immune system, this essay explores the evidence for the reasonable exposure of ourselves and our kids to pathogens, in order to boost their immune systems, the so-called Hygiene Hypothesis. As Philipp Dettmer writes in his book Immune: A Journey into the Mysterious System That Keeps You Alive:

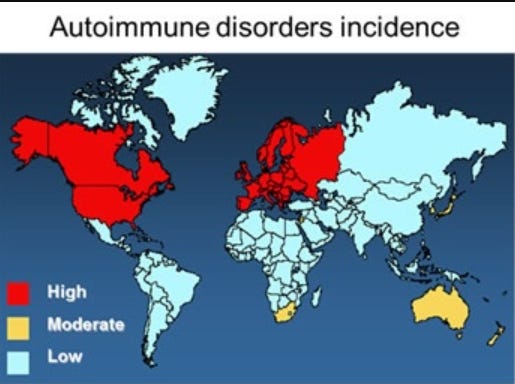

The latter half of the twentieth century saw two really weird and counterintuitive trend lines in developed countries. While dangerous infectious diseases like smallpox, mumps, measles, and tuberculosis were successfully pushed back and in some cases got to the verge of elimination, other diseases and disorders began to grow or even skyrocketed. The rates of diseases like multiple sclerosis, hay fever, Crohn’s disease, type 1 diabetes, and asthma have increased by as much as 300% in the last century. But this is not all: It seems like you can draw a direct line from how developed and rich a society is to how much of its population suffers from some kind of allergy or autoimmune disorder. The number of new cases of type 1 diabetes is ten times higher in Finland than it is in Mexico, and 124 times higher than in Pakistan. As many as one in ten of all preschool children in Western countries suffer from some form of food allergy while only around two in one hundred in mainland China do. Ulcerative colitis, a nasty inflammatory bowel disease, is twice as prevalent in Western Europe as in Eastern Europe. Around 20% of all U.S. Americans suffer from allergies. All of these disorders have two common denominators: either the immune system is overreacting to a seemingly harmless trigger, like pollen from blooming plants, peanuts, the excrements of dust mites, or air pollution (in a nutshell: allergies), or it is going a step further and is straight up attacking and killing civilian body cells, which we experience as autoimmune disorders like type 1 diabetes. All while humans are dying less from infections.

Why is this? As Dettmer explains:

When you are born, your immune system is like a computer. It has hardware and software and is in theory able to do a lot of things. But it doesn’t have a lot of data. It needs to learn which programs it needs to run and when. Who is a foe and who can be tolerated. So for the first few years of your life it collects information from its environment. It collects data from the microorganisms it encounters. It does so by processing “data” it collects from interactions with microbes. If it does not get enough microbial data and can’t learn enough, the risk rises that it will grow up to be overly aggressive and will later go on to attack harmless substances like peanuts or pollen from plants. A really famous study shed some light on how your environment in early childhood forms your immune system. The study looked at two distinct groups of farmers in the United States, the Amish in Indiana and the Hutterites in South Dakota. Both of these populations stemmed from religious minorities that emigrated from Central Europe to the United States in the 1700s and 1800s. Both groups have since not mixed with other populations but stayed genetically isolated, living lives shaped by similar and strong religious convictions. What made these two groups so interesting to study and compare is that both are genetically close, which made it easy to ignore genetics and focus on their lifestyle differences. And there is a huge difference between Amish and Hutterites: While the Amish practice a traditional style of farming, where single families have their own farms with dairy cows and horses that are used for field work and for transportation and in general avoid modern technology, the Hutterites live on large and industrialized communal farms, with industrial machines and vacuums and many amenities of the modern world. Consequently, researchers found a much higher rate of microbes and microbe poop in the houses of the Amish compared to the Hutterites. The rates of asthma and other allergic disorders are four times higher in Hutterites than in the Amish. So it seems growing up in a less-urban environment offers some protection against allergic disorders. Also, it is fair to conclude that a little bit of dirt does not harm you, in fact it might be good for you. Unfortunately (or fortunately, you decide for yourself) most people do not live on farms anymore. Today we don’t surround ourselves with the kind of diverse microbial ecosystem that we evolved in parallel to. We isolate ourselves from all kinds of natural environments. There is not one single factor but a bunch of different ones that all play together: The urbanization of the world has sped up drastically in the last century and in many developed countries the majority of the population lives in cities. And while not all cities are jungles made purely from concrete, the distance to something that resembles nature, with all its critters, makes a big microbial difference. These changes are pretty new in evolutionary terms because until the early 1800s the vast majority of the human population lived in rural areas. This development also coincided with the fact that step-by-step, in the last few decades, through the advent of entertainment and information technologies from TV to the internet, we got used to spending the vast majority of our time inside. In developed countries, “inside” means an artificial environment made from processed materials that, while not actually sterile, house a completely different ecosystem for a different set of microorganisms than the ones our ancestors adjusted to. As we said, until very recently in human history, people lived in houses made from natural materials like wood, mud, and thatch, all full of microbes that were all too familiar to our immune systems.

The modern reduction in baby’s early exposure to microbes sometimes starts right at birth:

The problem may start even earlier, literally at the beginning of life itself: Today a considerable percentage of babies are born via cesarean section. This is not ideal because in regular births the tiny human comes in close and intense contact with the vaginal and often fecal microbiome of their mother. So your birth is actually an important step in the microbial priming of your body and immune system. The microbiome of small children varies significantly depending on how they were born. Adding another puzzle piece in early life is the fact that fewer mothers are breastfeeding than in the past. Mothers’ breast skin and milk contain a vast and diverse array of substances that nurture the very young microbiome and a number of diverse bacteria. Evolution made sure that newborns get plenty of face time with the old and proven microbiome. Both C-sections and the lack of breastfeeding are correlated with a higher rate of immune disorders like allergies … Being allergic means that the immune system massively overreacts to something that might not be all that dangerous. It means that it mobilizes forces and prepares to fight, although there is no real threat present. About one in five people in the West suffer from some form of allergy—most commonly immediate hypersensitivity, which means that symptoms are triggered very quickly, within minutes of being exposed.

This tendency for breast feeding to boost immunity may even be relevant to a prominent lawsuit alleging that various baby formula is responsible for infant illnesses -- when it may be that the lack of breastfeeding, not the use of formula, is the cause. As reported in the Wall Street Journal:

Abbott Laboratories and Reckitt Benckiser [are being sued] for producing life-sustaining formula for pre-term infants, which could force the companies to pull their products from the market. Plaintiff attorneys have filed hundreds of lawsuits against the two companies for failing to warn that their products allegedly increase the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), a life-threatening intestinal disease afflicting premature and low-birth-weight babies. The first trial against Abbott began earlier this month in St. Louis County, Mo. The companies produce specialized formulas fortified with vitamins and ingredients that are specifically designed to address premature infants’ nutritional needs. The formulas are administered by doctors in the neonatal intensive care units because breast milk alone often doesn’t contain sufficient nutrients to sustain infants with low birth weights. But no good product goes unpunished by the lawyers looking for their next jackpot. The lawsuits cite studies that find infants who are breast fed have a lower risk of NEC. But it’s unclear what causes NEC. The National Institutes of Health says the condition may result from immaturity of the intestines combined with “infection and inflammation” stemming “from the growth of dangerous bacteria.” Scientists posit that breast milk may have particular properties that help prevent NEC. Recent randomized controlled trials show that the formulas and fortifiers don’t increase the incidence of NEC. The Food and Drug Administration, which regulates baby formula and labels, hasn’t required manufacturers to warn about an increased risk of NEC.

Dettmer then describes some of the ways people might boost their own immune systems:

Maybe one of the most important differences to our evolutionary past may be that modern diets contain vastly less fiber than they used to. Fiber is an important power food for a lot of useful and friendly commensal bacteria, and the fact that we just eat less and less of it means that we can’t sustain these little bacteria buddies in the numbers that we might need them. So while it doesn’t seem to make a difference if a house is clean or not, it does make a difference if it is surrounded by cows and trees and bushes and if dogs roam freely. So what can you take away from this chapter? Wash your hands at least every time you use the restroom, clean your apartment but don’t try to sterilize it, and clean the tools you use to prepare food properly. But let your kids play in the forest … On top of just eating right, the positive health effects of even moderate regular exercise have been known for a long time. Your body is made for movement and so moving it around a bit keeps a variety of systems in good health, especially your cardiovascular system. Working out also directly boosts your immune system, because it promotes good circulations of fluids throughout your body. In a nutshell, just by moving, stretching, and squashing your various body parts, your fluids flow better and more freely than if you lie on your couch all day. And good circulation is good for the immune system because it allows your cells and immune proteins to move more efficiently and freely, which makes them do their job better … To understand the role of stress and the immune system, we have to look back millions of years, to a simpler but much more cruel time in our developmental history. In order to survive, your ancestors had to deal with the evolutionary pressures the environment subjected them to. In the wild, stress is usually connected with existential danger, like a rival that crosses into your territory or a predator that wants to make you its meal. So for your ancestors it was a good idea to react strongly to perceived danger because if you acted decisively, then you were more likely to survive—if you were wrong and something was not actually dangerous nothing was lost. If you were slow to react to potential danger and you were wrong and it turned out to be actually dangerous, something bigger would probably eat you. As a consequence, organisms that were good at responding rapidly to a possible source of danger, a stressor, real or not, were more successful at surviving and reproducing than others who were not. Over time and through this selective pressure, our ancestors became fine-tuned to recognize stressors quickly and to react swiftly to them, often with automated processes. In mammals for example, this meant glands that are able to rapidly release stress hormones, which accelerated the delivery of oxygen and sugar to the heart and skeletal muscles and made it possible to react to a threat instantly and with power. Behavioral adaptations like the fight-or-flight response saved even more crucial time and helped them to survive in the wild. Because if you think you have spotted a lion in your peripheral vision, it is a better survival strategy to start running or to throw your spear than to carefully consider for a minute if that really was a lion or just a bush that sorta looked like one. In the context of these sorts of adaptations, it makes sense that your immune system also responds to stress. No matter if you fight or flee, in both cases, the likelihood that you will get wounded increases dramatically, which means that pathogenic microorganisms might have an opportunity to infect you, making your immune system immediately relevant. So one of the adaptations to stress was to accelerate certain immune mechanisms while slowing down others … [T]he nature of the stressors we encounter in the modern world is different than the ones we evolved with. In the past the lion either got you or you escaped—either way, your stress stopped. It rarely followed you around for weeks or months, like exam season or a large project for a demanding client. And so a mechanism that was meant to support short bursts of activity has turned into a chronic background noise. So what is the effect of chronic stress on your immune system? Well, as so often before, it’s very complicated and not at all straightforward … Stress also releases hormones like cortisol that shut down and suppress your immune system, making it weaker and less able to do its job properly in a variety of ways. Wounds heal slower, infections are more likely to break out and to cause disease … Chronic stress means a chronic release of cortisol, which generally slows your defense systems down. A pretty strong connection has also been made in recent years between the onset of autoimmune diseases and stress. And stress also seems to be one of many risk factors for tumor progression. OK, so this range of possible diseases could not possibly be broader—it seems that chronic stress negatively affects every single area where the immune system is supposed to protect you. So if you are still looking for ways to boost your immune system, an actual tangible thing you can start doing today is to try to eliminate stressors in your life and to take care of your mental health. This might seem like pretty daft advice because it is so obvious, but the connection between your state of mind and your health is very real. So helping people live happy and fulfilled lives with less stress and depression would probably have considerable health benefits for our societies.

Unfortunately, as explored in a previous essay, much of our modern politics of premised on false notions that induce in people an external “locus of control” that increases their stress levels and reduces their mental health.

This concludes this essay series on the human immune system.