The Human Immune System – Part 2

Our skin.

Continuing this essay series on the human immune system, this essay explores the human body’s first line of defense: our skin. As Philipp Dettmer writes in his book Immune: A Journey into the Mysterious System That Keeps You Alive:

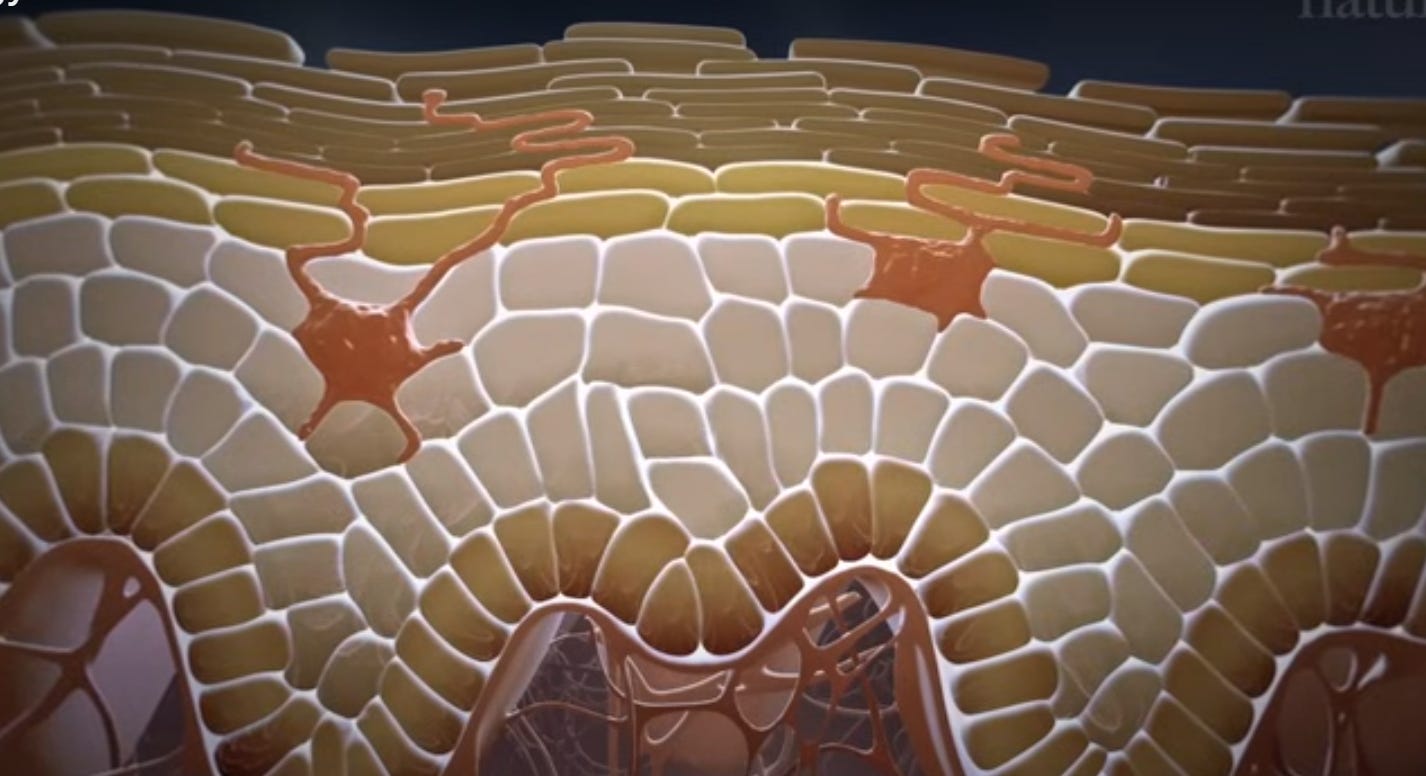

Let us see what happens when a few bacteria successfully make it into your body! But to get there, they first need to overcome a mighty barrier: The Desert Kingdom of the Skin. To be literally tough, not just figuratively, your skin cells produce a lot of keratin— a very tough protein that makes up the hard part of your skin, nails, and hairs. So your skin cells are hardy fellows, filled with special material that makes them hard to break … The skin stem cells constantly make new skin cells, and each new generation pushes the older ones further up. So your skin cells are constantly pushed upward by younger skin cells emerging below them. The closer they get to the surface, the more they need to become ready to be living defenders. And so as your skin cells mature, they develop long spikes and interlock with the other cells around them to form a dense and impassable wall. Next your skin cells begin manufacturing lamellar bodies, tiny bags that squirt out fat to create a waterproof and impermeable coat that covers the cells and the little bit of space that is left between them. This coat does three things: It acts as another physical border that is extremely hard to pass; it makes it easier to dispose of dead skin cells later on; and it is filled with natural antibiotics called defensins, which can straight up murder enemies on their own … As the skin cells are pushed up further towards the surface they begin preparing for their final job: Dying. They become flatter and bigger and begin to stick together even tighter until they merge together into inseparable clumps. And then they shed their water and kill themselves. Cells killing themselves is nothing special in your body, every second at least one million of your body cells go through some form of controlled suicide. And usually, when cells kill themselves, they do so in a way that’s easy to clean up their corpses. But in the case of your skin cells, their dead bodies are actually very useful. You could even say that the purpose of their life is to die in the right place and become neat carcasses. The wall of merged, dead skin corpses is consistently pushed upward. Up to fifty layers of dead cells, fused together on top of each other, form the dead part of your skin that ideally covers your whole body. When you look at yourself in the mirror, what you are really seeing is a very thin film of death covering your alive parts. As this dead layer of your skin is damaged and used up by the process of you living your life, it is constantly shed and replaced by new cells moving up from the stem cells deep below. Depending on your age, it takes your skin between thirty and fifty days to completely turn over. Every single second, you shed around 40,000 dead skin cells. So your outer border wall is constantly producing, emerging, and then discarding. Think about how ingenious and amazing a defense this is. Not only are the walls of the Skin Border Kingdom consistently replaced and fixed, as they move up they get coated in a fatty layer of passive and natural antibiotics. And even if enemies find a place to make their home and start eating away at the dead skin cells, they are consistently shed away from the body, making it much harder to gain a foothold on the skin.

Our skin has evolved to be a nasty environment for intruders:

When it is warm, humans sweat a lot, which both cools us and also transports a lot of salt to the surface. Most of it is reabsorbed but some of it remains, overall making your skin a pretty salty place, which many microbes don’t like. As if that’s not enough, sweat contains even more natural antibiotics that can passively kill microbes. So your skin does everything it can to be a real hellhole. From the perspective of a bacteria, it is a dry and salty desert filled with geysers that spit out toxic fluid and flush enemies away. But this is still not all. Another one of the great passive defenses of your skin is that it is covered in a very fine film of acid, appropriately called the acid mantle, which is a mixture of sweat and other substances secreted by glands below your skin. The acid mantle is not so harsh that it would hurt you, it just means that the pH of your skin is slightly low and therefore slightly acidic and that is something a lot of microorganisms don’t like … Bases: pH is one of those things that is often not properly explained or quickly forgotten once it is. For once, scientists gave something a great name: pH is short for POWER OF HYDROGEN, which is exciting and easy to remember. But then scientists decided to abbreviate it. Disappointing to say the least. Without getting too deep into it, the POWER OF HYDROGEN is a scale that describes how many hydrogen ions are present in a water- based solution. “[P]ower.” Power in this context doesn’t mean that the hydrogen is extra strong or anything like that. We are dipping into the wonderful universe of math here. This is “math power,” correctly called exponential. So going up 1 POWER on the pH scale means having ten times fewer hydrogen ions. Going up 6 POWER on the pH scale means having one million times fewer hydrogen ions. (Why is going up the scale meaning fewer ions? Because the scale is inverted … A lot of hydrogen ions means that something is acidic: Think of a tasty lemon or not as tasty battery acid. A low number of hydrogen ions means something is basic or alkaline, for example soap or bleach, both not very tasty. In general you don’t want too many or too little hydrogen ions in a fluid because they will either take or donate protons. That’s fine in weak acids, like when you squeeze a lemon over your food to make it taste better, but if a substance is either too basic or acidic it will act corrosively on your body. Corrosion means that it will destroy and decompose the structures your cells are made of and cause chemical burns. Small differences in POWER OF HYDROGEN make a bigger difference in the world of microbes … The acid mantle has another great passive effect mostly geared towards bacteria: The inside and outside of your body have different pH levels. So if a bacterium adapts to the acidic environment on the skin and then gets an opportunity to enter the bloodstream, for example, through an open wound, it has a problem: Your blood has a higher pH. So the bacterium suddenly finds itself in an environment that it is not adapted to, with very little time to do so, which is a considerable challenge to some species.

As Dettmer writes, “we” are composed of not just the cells with our own DNA, but also of billions of other entities:

Aside from your gut, which is basically made for and ruled by bacteria your body has invited in, your skin is the second most populated place of your body in terms of guests that are not you, but are indeed welcome … Overall, an average square centimeter of your skin is home to around a million bacteria. About ten billion friendly bacteria in total populate your outsides right now.

And regarding the skin and viruses:

[W]e should mention that the way the skin is built, it is practically immune against viruses. Because these little parasites can infect only living cells and the surface of your skin consists only of dead cells, there is nothing to infect here! Only very few viruses have evolved ways to infect your skin, so bacteria and fungi are of much greater concern to your skin.

Of course, your skin, as a barrier to pathogens, can be breached:

Despite all those amazing defenses, the kingdom can be breached. Skin cells may be tough, but the world is tougher. And there are always bacteria ready to take a chance if they get one. Let us witness the immune system in real action for the first time … [Say] a long and rusty nail penetrates the sole of your shoe … You take your shoe and sock off to look and it’s nothing terribly serious, only a little bit of bleeding … Meanwhile your cells had a pretty different experience. When the nail penetrated your shoe, its tip entered your big toe. It ripped through your skin like a pointy piece of metal would. For your cells, it was an average day until suddenly, their world exploded … Much worse though, it was covered with soil and dirt and hundreds of thousands of bacteria that suddenly found themselves beyond the gates of your otherwise impenetrable skin border wall … Immediately, bacteria spread into the warm caverns between helpless cells, ready to consume nutrients and explore a little. This here is much better than soil! … And the soil bacteria are not the only unwelcome visitors. Thousands of bacteria that did their thing on the surface of your skin and in your moist socks now also decide to check out this paradise that has just appeared out of nowhere.

Your Innate Immune System then begins responding:

Macrophages … are the largest immune cells your body has to offer … Macrophages are able to stretch out parts of themselves, a bit like the arms of an octopus, guided only by the smell of the panicked bacteria. When they manage to grab one of them, its fate is sealed. The grip of a Macrophage is too strong, and resistance is futile, as it pulls the unlucky bacteria in and swallows it whole to digest it alive … As the Macrophages devour one enemy after another they realize that they can at best slow this invasion down, not stop it. And so they begin to call for help, sending out urgent alarm signals, and start preparing the battlefield for reinforcements that will arrive shortly. Lucky for them, backup is already under way. In the blood thousands of Neutrophils have heard the cries for help and smelled the signs of death and begun to move. Immediately they begin hunting and devouring bacteria whole, but with much less care for their surroundings. Neutrophils are on a tight timer: Once active they only have hours before they will die of exhaustion as their weapons do not regenerate. So they make the best of the situation and use them freely— not only killing enemies but also causing real damage to the tissue they should be protecting in principle. But collateral damage is not their concern at this moment or ever, as the danger of bacteria spreading through the body is much too grave to consider civilians. But they do not only fight, they also self- sacrifice— some of them explode, casting wide and toxic nets around themselves in the process. These nets are spiked with dangerous chemicals that seal off the battlefield, trap and kill bacteria, and make it harder for them to leave and hide.

From our own vantage point, we can see very little of our immune system’s response, and what we can see is limited to scabs, inflammation, and pus:

Back in the world of the humans, you sit down again to take a second look at [your injured foot]. The small wound is already covered by a very thin film of crust. At this point the wound has already closed superficially as millions of specialized cells from the blood flooded in the battlefield: Platelets, blood cells that exist mainly to act as an emergency worker that closes wounds. They produce a sort of large, sticky net that clumps themselves and unlucky red blood cells together and creates an emergency barrier to the outside world, stopping blood loss rather quickly and preventing more intruders from entering. This enables fresh skin cells to slowly start closing the enormous hole in the world … What you experience as a light swelling is a purposeful reaction of your immune system. The cells fighting at the site of infection started a crucial defense process: Inflammation. This means they ordered your blood vessels to open up and let warm fluid stream into the battlefield, like a dam opening up towards a valley. This does a few things: For one, it stimulates and squeezes nerve cells that are deeply unhappy about their situation and send pain signals to the brain, which makes the human aware that something is wrong and an injury occurred. Still, that does not help with the hundreds of thousands of enemies that already made their way in, but luckily the rush of fluid caused by the inflammation carries a silent killer into the battle zone. Many bacteria get stunned, or begin twitching as dozens of tiny wounds mysteriously appear on their surfaces and make them ooze out their insides, which is pretty bad and kills them. We’ll get to know this silent killer intimately at a later point … [Back on the surface of the skin, a] strange- smelling substance can emerge from wounds a day or two after they have been infected. Pus is the dead bodies of millions of Neutrophils that fought to the death for you, mixed in with ripped- apart remains of civilian cells, dead enemies, and spent antimicrobial substances.

And while we’re on the subject of pus, here’s what Dettmer says about mucus:

The insides [of your lungs, your guts, mouth, and respiratory and reproductive tracts] are lined with what you could call your “inside skin.” Unfortunately, the correct name is Mucosa. But to make it a bit more badass we will call it the Swamp Kingdom of the Mucosa. While most of your continent of flesh is pretty sterile and devoid of microorganisms, devoid of other, your swamp kingdom is constantly in contact with all sorts of other— pieces of foodstuffs that need to be taken in, indigestible stuff that just passes through, friendly bacteria that get a free pass and are allowed to stay in your gut, all sort of particles that flow through the air and are breathed in, from pollution to dust. Imagine it reacting violently to every little flake of dust that you breathed in. No, the immune system of the swamp kingdom can’t be as aggressive as the immune system in other parts of the body or it would simply destroy the places made for the exchange of gases and resources, which can make your life miserable or even kill you (as it indeed does for many people who suffer from autoimmune diseases or allergies, but more on that later). The first line of defense employed by the swamp kingdom is the swamp itself. The mucus layer. Mucus is a slippery and viscous substance that behaves a little bit like watery gel. You know it as the slimy stuff in your nose that becomes especially visible and disgusting when you have a cold— but it is actually all over your insides— in your gut, your lungs, your respiratory system, your mouth, the inside of your eyelids. Mucus is continuously produced by Goblet Cells, which are not important for the story of the immune system but they look really funny. Imagine them as weird squished worms that have to vomit all the time to create the mucus layer. And mucus is not just a sticky barrier but also filled with unpleasant surprises similar to the desert kingdom: salts, weaponized enzymes that can dissolve the outsides of microbes, and special substances that sort of sponge up crucial nutrients that bacteria need to survive, so they starve to death inside the mucus … [H]ave you ever asked yourself how it is possible that you have a sack filled with literal acid inside of you? Well, the mucosa inside your stomach acts as a barrier that keeps the acid at a distance and protects the cells making up your stomach wall … Again imagine your guts as a long tube reaching through you, trapping a bit of outside inside you. On this outside, on your gut mucosa, around thirty to forty trillion individual bacteria from around 1,000 different species and tens of thousands of species of viruses make up your gut microbiota (the vast majority of viruses in your gut are hunting the bacteria living there and not interested in you) … After [chewing] the ground-down foodstuffs are swallowed, they get to have a moment in an ocean of acid in your stomach. Which is not only helpful for your digestion and helps break down tough meat or fibrous plants, many microorganisms don’t like being submerged in literal acid and die here, making the job of your immune system much, much easier … After the stomach the journey continues through your intestine, which is between ten and twenty-three feet long and constitutes the longest stretch of our digestive tract. Over 90% of the nutrients you need to survive are absorbed here. And here a lot of the bacteria buddies you need to survive spend their time assisting with breaking down the food even more and enabling your body to take up its nutrients … Your intestinal immune system really does not want to cause inflammation if not absolutely necessary, because inflammation means a lot of extra fluid in the intestines, which you experience as diarrhea. Diarrhea doesn’t just mean watery poop, but also damage to the very sensitive and thin layer of the cells that take up the nutrients from your food. And diarrhea can rapidly dehydrate a patient to dangerous levels. Unbeknown to most people, diarrhea is still a huge killer, responsible for about half a million dead children each year. So millions of years ago when we evolved, our bodies and immune systems learned to take inflammation in the intestines very seriously. As a consequence the Macrophages guarding your intestines have two properties: Firstly, they are really good at swallowing bacteria. And secondly, they do not release the cytokines [explained in the next essay] that call in Neutrophils and cause inflammation … [One of our antibodies] IgA is really good at something ..: with its four pincers that reach in opposite directions, it is an expert at grabbing two different bacteria and clumping them together. So a lot of IgA can create huge clumps of helpless bacteria that are transported out of the body as part of your poop. All in all, around 30% of your poop consists of bacteria—and a lot of them have been clumped up by IgA Antibodies (most disturbingly, around 50% of them are still alive when they leave you).

And here’s a quick aside regarding snot:

There is the common wisdom that the color of your snot can tell what kind of infection you have and if it is just a cold or a flu, but that is not true: the color just tells you how severe the inflammatory reaction inside your nose is, not what caused it. The more colorful, the more Neutrophils have given their life.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll examine what happens when pathogens get past your skin defenses.