The History of Communism – Part 3

How communism received an image boost after World War II, and took advantage of former Western colonies; also Maoism in China and the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia.

Continuing this essay series on the history of communism using Sean McMeekin’s To Overthrow the World: The Rise and Fall and Rise of Communism, this essay will explore how communism received an image boost after World War II, and took advantage of former Western colonies. It will also explore the Maoist form of communism in China and the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia.

As McMeekin writes:

For all the failures of Communism at home, the Soviet government was considerably more successful in promoting its image abroad … [I]t is astonishing to reflect that this period of high Stalinism, c. 1928–1938, also marked a peak in Communist prestige internationally judged on almost any criterion, from the inward migration of Western laborers and managers to design and man Stalin’s blast furnaces and factories to the singing of the regime’s praises by Western “fellow travelers” such as George Bernard Shaw. Communist party membership figures grew, as did the ranks of Western agents who enlisted to spy for Stalin—often free of charge … [T]he plausible (though dubious) idea that Stalin’s USSR was the most principled opponent of Hitler’s Germany seduced thousands of Americans into the Communist orbit. While many of these were “fellow-traveling” sympathizers who showed up at a few meetings, many others were card-carrying party members (the number of the latter had risen from 13,000 to 80,000 by 1938). Still others were paid Soviet informants working inside the US government: according to contemporary NKVD records, there were 221 of these, though, according to the “Venona” telegrams later decrypted by US intelligence, there may have been as many as 329. The most highly placed Soviet spies were Alger Hiss, who headed the Office of Special Political Affairs in the State Department from 1936 to 1947, where he had access to classified material relating to US military strategy, and Harry Dexter White, assistant secretary and second-in-command at the Treasury Department under Henry Morgenthau, a close friend of President Roosevelt’s … The story of the Soviet triumph against Nazi Germany is well worn into popular legend, nowhere more dramatically than in Russia itself, where the “Great Patriotic War” narrative has sustained rulers from Stalin to Putin. In view of the stupendous sacrifice of the Soviet peoples, who lost somewhere between 25 million and 30 million war dead between 1941 and 1945, it is not hard to see why the story retains its epochal significance for Russians and the other peoples of the former Soviet Union. Westerners, too, have tended to view the Soviet victory as a heroic blood sacrifice almost too sacred to question, no matter how oppressive the treatment by Stalin’s regime of its own people might have been, even—indeed especially—when they were resisting, and ultimately defeating, the most barbaric invasion in human history. In view of the human losses, it may seem impolitic to throw shade on Stalin’s victory, but there has always been something dubious about his regime’s claim to have proved itself, to have demonstrated the supremacy of Communist central planning and social organization, by “winning” a war while losing nearly 30 million people, of whom 15 million or 16 million were civilians. As Max Hastings pointed out in his best-selling war history Inferno, the number of Red Army soldiers shot by their own side alone (about 300,000) is “more than the entire toll of British troops who perished at enemy hands in the course of the war.” Then there is the awkward circumstance that saw the Soviet war economy become almost wholly reliant on “capitalist” Lend-Lease supplies from 1941 to 1945, from raw materials and foodstuffs to industrial inputs and finished products. Oblivious to both horrendous NKVD disciplinary measures and the Lend-Lease story, which was little reported at the time, many westerners generously credited Stalin and his government with the victory.

The communists also took advantage of the post-war turmoil:

[T]he collapse of civilization across the once-prosperous lands of Central Europe augured well for Communist fortunes. The arrival of the Red Army into devastated cities such as Warsaw and Budapest in 1945 brought not just political prestige in the abstract, as in France and Italy, but the promise of the restoration of law and order—of a sort—along with the promise of retribution for the war’s victims. Many of those who had suffered the horrors of Nazi occupation viewed the Red Army as liberators, even many Poles, who might have resented the role Stalin’s armies played in the destruction of their country in September 1939, but had suffered for far longer (so far, at least) under the German yoke. The Soviet occupiers wore out their welcome quickly, however, undermining the reputation and popularity of Communism in Eastern Europe just when it should have been peaking after the great Soviet victory over Nazi Germany. That the Red Army carried out mass rapes and looting in Berlin, the belly of the Nazi beast, was not surprising in view of the horrendous suffering of the Soviet peoples at the hands of the Barbarossa invaders, but rapacious Russian behavior was not limited to Prussia. Not just Germans but thousands of Polish, Hungarian, Romanian, and Czech women were raped as the Red Army crashed into Central Europe in 1945. The Genghis Khan treatment by the Soviet occupiers extended to property theft as well, establishing a precedent that did not bode well for the popular reception of Communism. Officially, each Red Army soldier was limited to five kilograms of loot after conquering Berlin, Budapest, and other large cities, although most Red Army officers hardly bothered to search their men … [I]t was not just greed but cultural shock that motivated Soviet looting, as serving men and officers alike were bewildered by the material wealth of the capitalist countries, replete in so many things Communist Russia lacked, from toys and bicycles to varieties of liquor, from kitchen accoutrements to men’s and women’s clothing, perfume, and lingerie.

In addition, Russian communists took advantage of the political vacuums left when Western colonizing countries left their former colonies:

With Europe’s “capitalist” empires all but declaring bankruptcy, the USSR could embrace the cause of the colonized peoples. On his visit to the United States in 1959, he addressed the UN General Assembly in New York, saluting “the heroism of those who led the struggle for the independence of India and Indonesia, the United Arab Republic [as the union of formerly French Syria and formerly British Egypt under Nasser was then called] and Iraq, Ghana, Guinea and other states.” Still, although these colonized peoples had “won independence,” Khrushchev continued, they were still “cruelly exploited by foreigners economically.”“Their oil and natural wealth is plundered,” he said. “It is taken out of the country for next to nothing, yielding huge profits to foreign exploiters.” By working together with leaders of newly independent colonies, the Soviets could reverse their exploitation, helping them nationalize resources and providing the technology they needed—absent a “capitalist” profit motive (though still taking payment, presumably) … Basking in applause after this anti-imperialist pitch, Khrushchev enjoyed himself so much that he returned to New York in the fall of 1960, bear-hugging all the new national leaders from Africa and delivering twelve speeches to the General Assembly. In January 1961, he made the “sacred” anti-imperialist struggle of the Third World a state priority of the Soviet Union, vowing to “bring imperialism to its knees.” … Khrushchev publicly embraced Castro during his visit to the United Nations in September … Castro and his charismatic Argentinian adviser and chief executioner, the former doctor Ernesto “Ché” Guevara, became romantic heroes of anti-imperialism … Castro’s one-party dictatorship imprisoned and tortured thousands of dissidents, epitomized in the mass executions of nearly 700 political prisoners on Ché Guevara’s orders in La Cabaña prison in 1959. Some 1.4 million Cubans had left Cuba by 1962, nearly a fifth of Cuba’s population of 7.14 million, the vast majority of them heading for South Florida, where Cuban exiles would soon predominate in and run the great city of Miami … Ché saw his fame ratchet up to even higher levels after he died a martyr’s death trying to export Communist revolution to Bolivia—and thereafter the rest of South America—in 1967, when he was captured and executed by US-trained Bolivian soldiers in October. Although Ché had the blessing of the USSR for his Bolivian scheme—he had received instructions, and a new passport, in Moscow the previous October—it is curious that his death was mourned by more people in Washington, DC (50,000), than in Moscow … Ché was the single most admired celebrity among American college students in a 1968 poll, and he has never since lost his mojo. Guevara, as the commentator Alvaro Vargas Llosa observed in a sardonic tribute, became and remains the “quintessential capitalist brand” of global Communism: “His likeness adorns mugs, hoodies, lighters, key chains, wallets, baseball caps, toques, bandannas, tank tops, club shirts, couture bags, denim jeans, [and] herbal tea,” Vargas Llosa wrote, along with “those omnipresent T-shirts” with the famous Alberto Korda photo of the bearded “socialist heartthrob in his beret.”

When communism swept over China under the leadership of Mao Zedong in 1949, it turned to a Great Terror of its own. As McMeekin writes:

As in Russia after the Revolution, strict food rationing was introduced, as households were registered with the government, censorship and state control of print media and radio were introduced, industry nationalized, and young students and workers were mobilized into subbotnik-style work battalions to clean up and rebuild the infrastructure of a war-damaged country. Mao introduced Communist innovations, too, dividing families up into sixty social “classes,” with a clear proletarian hierarchy between “revolutionary” cadres, soldiers, martyrs, and industrial workers at the top, and bourgeois capitalists, “landlords,” and “rich peasants” at the bottom. Mass arrests of class enemies began almost immediately on the pretext that, despite Chiang’s departure to Taiwan, the war with the Nationalists was still ongoing. In Hebei province, home to the capital, Beijing, some 20,000 “counter-revolutionaries” were executed in the first twelve months after Mao proclaimed the PRC. Social “parasites,” such as prostitutes, beggars, and vagrants, were rounded up in the thousands and sent off to prison or reeducation camps. Brothels and gold and jewelry shops were closed down as Western “capitalist” excrescences. Women abandoned lipstick and makeup, and everyone either hid away or sold off their jewelry, watches, and rings. “The fashion was simplicity almost to the point of rags,” one female Communist recalled of the liberation years … [T]he CCP terror that followed was similar to Lenin’s Red Terror, but in its scale, and the use of provincial death and deportation quotas, it soon resembled Stalin’s Great Terror, with the sinister new twist that quotas were set per thousand residents (i.e., 1 killed per 1,000 and 9 deported to labor camps). To summon the necessary hatred, mass rallies were held in Chinese cities, with CCP spokesmen asking crowds what should be done with “spies and special agents hiding in Beijing,” or to “feudal remnants” such as “fishmongers, real-estate brokers, water carriers and nightsoil scavengers.” The answer that usually came back was “Execute them by firing squad.” At a CCP convention in 1954, Chinese bureaucrats reported having executed 710,000 people—a figure historians now think is too low—and sent millions more to forced-labor camps. Mao himself boasted, at one point, that 800,000 “counter-revolutionaries” had been “liquidated.” PRC files show that some 450,000 businesses were targeted, while at least 2.5 million people were imprisoned or sent to reeducation or forced-labor camps, roughly 1.2 percent of the rural population but fully 4 percent of China’s urban population … In the cultural sphere Mao channeled Hitler more than Stalin. The anti-intellectual thought-reform campaign saw public book burnings so colossal that they were measured by volume. In Shanghai, 237 metric tons of books were torched. In Shantou, a coastal port where European influence had been marked, 300,000 volumes were thrown onto a giant bonfire that raged for three days. Western-style books, music, and films were either destroyed or hidden away in CCP archives, replaced by new Communist tunes, hymns, and newsreels as the new Sino-Soviet Friendship Association, with 120,000 branches in China, launched the “Learn from the Soviet Union” campaign, which flooded the country with Soviet Communist literature, films, and school textbooks.ii While some enduring Chinese cultural traditions, such as Confucianism and Buddhism, were reluctantly tolerated for the time being, Taoism and Chinese Christianity, minority but mainstream faiths, were ruthlessly persecuted. The Catholic Church, with 3 million adherents, saw nearly 13,000 of its 16,000 churches shut down, torched, or razed to the ground, enough to reduce the number of parishioners by nearly half … China’s people, already exhausted by a decade of invasive governance, were now sent into an abyss of forced-labor madness. First came the massive dam projects to harness China’s rivers for electric power and irrigation. This initiative gave its name to Mao’s broader push, the “Great Leap Forward” (Ta-Yo-Tsin). With a certain callous honesty, Mao’s commissars did not even pretend, like Stalin’s agricultural planners in 1928, that they would be able to deploy hundreds of thousands of tractors to till the soil. Rather, China would deploy its one comparative advantage—its hundreds of millions of people, perhaps numbering about 650 million, the vast majority of them illiterate, desperately poor farmers and villagers—to transform the landscape with muscle power and crude hand tools. The rural population would dig up soil and rocks during the slack winter months to build dams and reservoirs and irrigation channels. No one knows for sure how many people died digging up China’s earth with “picks, shovels, baskets and poles” between 1957 and 1960, but new research suggests the number of victims was in the hundreds of thousands. While digging up and carting around soil and rock, collecting animal and human waste, tearing down chicken coops, and even melting down utensils and tools in backyard furnaces could be done with muscle power and simple tools, ramping up Chinese industrial production to Western levels would require imported machinery. As Mao confessed in October 1957, “If we want to build socialism, we need to import technology, equipment, steel, and other necessary materials.” Like Stalin’s First Five-Year Plan, Mao’s ambitious industrial targets necessitated cruel triage, as the only things China produced in enough quantity to export were grain, rice, pork, nuts, seed oils, and clothing—the very things people needed to survive. And so China ramped up food exports in 1958 and 1959 to pay for industrial imports even as food shortages began to bite, shipping 4.2 million metric tons of grain abroad in 1959 alone. Unlike Stalin, who had manipulated gullible (or cynical) Western journalists like Walter Duranty to camouflage his murderous food-export triage, Mao and his advisers boasted about it. As Zhou Enlai wrote in November 1958, “I would rather that we don’t eat or eat less and consume less, as long as we honor contracts signed with foreigners.” … The result of the radical overturning of traditional Chinese agriculture, and the forced export of dwindling yields of grain, seed oils, and pork to pay for industrial imports, was a famine of unprecedented scale, dwarfing even the horrors of the Soviet Holodomor. China, to be sure, had known terrible famines before, as recently as 1928–1930, which had cost the lives of 2 million or 3 million. But this was nothing like the humanitarian catastrophe that spread across the country from 1958 to 1962. While, owing to CCP control of the central archives, we may never know the full extent of China’s suffering, intrepid researchers have been working for years to collate material from local archives, including at least one major CCP semiofficial investigation conducted in 1979, during a post-Mao thaw, along with death certificate records for the years before and after 1958, which allow demographers to estimate “excess deaths.” The “normal” death rate across the country, already hugely elevated in 1957 owing to years of privation and repression, was something like 11 percent; this rose to an average of 15 percent during the Great Leap Forward years, peaking at 29 percent in 1960. In Anhui province, in North Central China, the death rate soared to an almost unfathomable 68 percent of the population in 1960 … [E]ven the Chinese government admitted in 1988 that there had been at least 20 million famine deaths. The best independent estimates for excess Chinese deaths during the Great Leap years come out between a low end of 32 million, calculated by a Chinese demographer, Cao Shuji, who worked with local party records, and the “43 to 46 million” estimated by Chen Yizi, who headed the CCP research team in 1979–1980 (a figure Chen Yizi published only after fleeing China following the Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989). Frank Dikötter, in his groundbreaking 2010 study Mao’s Great Famine, concluded after years of researching all available datasets that “the death toll stands at a minimum of 45 million excess deaths.”

China launched a massive campaign to purge itself of any ideological opposition. As McMeekin writes:

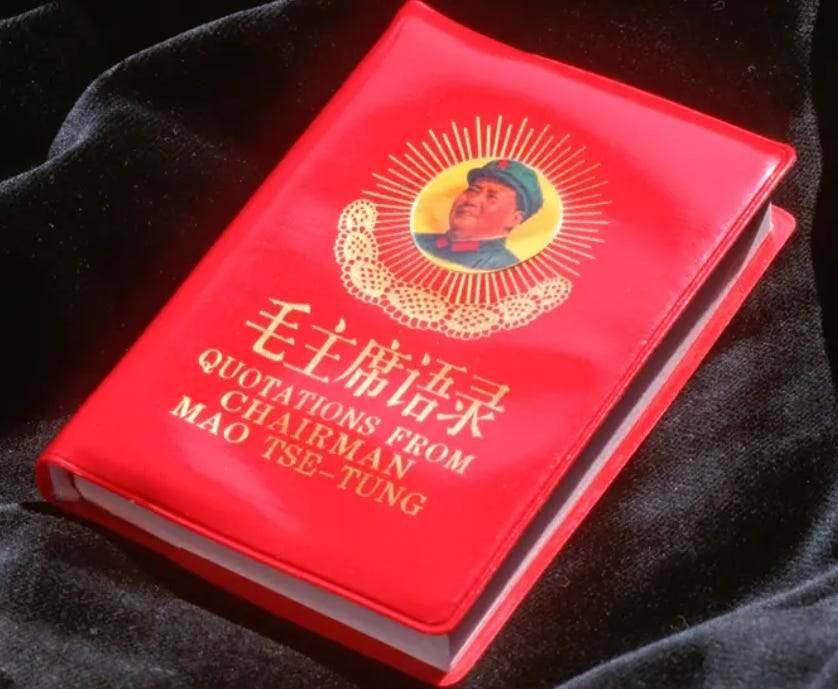

Mao attacked the Chinese Ministry of Culture, which, he said, should be renamed the “Ministry of Dead People” in view of its reactionary tendencies. Among these benighted tendencies was the old “mandarin” examination system for enrolling Chinese government bureaucrats, which Mao weakened by dumbing down the exams, insisting that, to avoid any advantage for “bourgeois” children, students be given the questions in advance and be allowed to copy clever students’ answers—that is, cheat on class grounds. Even dozing off in class Mao praised: there was no reason for good proletarian children to “have to listen to nonsense, you can rest your brain instead.” In May 1964, a mimeographed compendium of Mao’s quotations was distributed to the People’s Liberation Army. Officially titled Quotations from Chairman Mao Zedong, but soon known colloquially as the “Little Red Book,” it included this unsubtle inscription: “Read Mao’s book, listen to Chairman Mao’s words, act according to Chairman Mao’s instructions and be a good fighter for Chairman Mao.” … [T]here was something new in Mao’s Cultural Revolution, a ramping up of generational conflict against everything “old,” which represented an escalation in Communist radicalism … The foot soldiers who manned Mao’s big-character poster campaign launched in May–June 1966 … were mostly teenagers at secondary school, who were told by the government, in a June 3 decree launching the Cultural Revolution in schools, to stop attending class and start denouncing their teachers. Teachers and principals were heckled and forced to wear “dunce camps” or self- denouncing big- character posters (“ I am a Black Gang Element!,” or “I am an Anti- Party Intellectual”) tied around their chests or necks with weights, and were then assigned menial and humiliating work tasks, or in some cases “forced to kneel on broken glass.” Fellow students, too, were denounced if they refused to join the terror campaign against teachers. The Cultural Revolution Group set a quota mandating that 1 percent of students and teachers nationwide be labeled “rightists” or “counter- revolutionaries” and ritually abused, with a target goal of 300,000 victims. On June 13, China’s university exam system was declared null and void … It was now open season on unpopular, hesitant, or simply elderly Communist party leaders in China, whom angry young students and soldiers, forming armed groups called “Red Wind” or “East Wind,” devoted to Chairman Mao’s Cultural Revolution (soon shortened to simply “Red Guards” [Hung-Wei-Ping]), were exhorted to smoke out. The first victim of the Red Guards was the female vice principal of a girls’ school in Beijing, Bian Zhongyun, who on August 5 was splashed with ink, forced to kneel, beaten with nail-spiked clubs, and dumped in a garbage cart, where she died of her wounds. Among the schools that saw similar horrors that August was Beijing’s 101st Middle School, where Mao himself had sent his own children. Ten unfortunate teachers of this junior high school were ritually tortured and then “forced to crawl on a path paved with coal cinders,” after which their Red Guard tormentors wrote “Long Live the Red Terror” with their victims’ blood on the wall of the room where they had tortured them … Mao summoned more than a million children and teenage students to Beijing’s Tiananmen Square … on August 19, 1966, where he, Lin Biao, and Zhou Enlai exhorted these future Red Guards to “strike down all power- holders walking the capitalist road, all bourgeois reactionary authorities, all bourgeois royalists, all bourgeois rightists, all freaks and monsters,” and “to destroy all old ideas, old culture, old customs and old habits of the exploiting classes.” It was an invitation to ritualized violence, not just against an alleged social class of oppressors, as in Lenin’s Red Terror, or recalcitrant party leaders or generals, as in Stalin’s Great Terror, but against anyone older or old- fashioned, or who annoyed the Red Guards by their very manner of being. Teachers, school principals, prominent writers, filmmakers, musicians, adults who wore eyeglasses, women who wore high heels, and men with “long, western haircuts” were surrounded, ritually denounced, beaten, and tortured. Hundreds were killed each day in Beijing, peaking at 200 a day toward the end of August, adding up to 1,700 killed by late September. In Daxing, a rural village near Beijing, 300 “landlords” were killed along with their families, their corpses hurled into “disused wells and mass graves.” Scenes of horror abounded, epitomized in the eyes of one British diplomat by the “sight of two old ladies being stoned by small children.” … While elderly or “bourgeois” Chinese furnished most of the victims, not even the foreign community was immune. On August 25, 1966, Red Guards broke into the fortified Beijing compound hosting the Sacred Heart Academy, a Catholic school operated by French nuns, and plastered the walls with posters reading, “Get out, foreign devil!” and “Chase out running dogs of imperialism.” The Red Guards then took hostages and presented an ambitious list of demands: Abolish the taxis and send the cars to villages. Prohibit the sale of gold, fish, birds, antiques and foreign goods … Bicycles should be free. House owners should transfer their property to the state … Bourgeois element should be made to do manual work. Cinemas, theaters and bookshops should be decorated with portraits of Mr Mao. Luxury restaurants abolished, business must serve workers, peasants, soldiers. Loudspeakers set up on every street to broadcast directives. Perfumes, jewelry and non-proletarian clothes and shoes surrendered. No more first-class rail wagons and seats. All paintings of bamboo and non-political themes abolished. All books not representing Mao’s thought should be burned. Bourgeois actors should only be allowed to play unsympathetic characters. All pedicabs should be peddled by bourgeois themselves.

As McMeekin writes, even Soviet journalists were astounded by the horrors unleashed in China:

Soviet and Western journalists alike were horrified when reports emerged of Red Guard assaults on libraries as repositories of “old” culture, often accompanied by book burnings … Christian churches and cathedrals were torched, along with ancient Chinese pagodas, Buddhist temples, and other cultural monuments. Even the sacred Confucius cemetery in Qufu, final residence and resting place of the great teacher, was not immune: a band of some 200 Red Guards broke in and desecrated the tombs … Flower shops, too, were targeted for destruction, on the idea that ornamental plants and flowers were wasteful “bourgeois” indulgences. Cats, seen as decadent “bourgeois” pets, were massacred in Shanghai and other cities. Apartments were searched for “capitalist” extravagances, from paintings and pianos to musical instruments, antiques, porcelain, and silverware … In addition to being deprived of their property and often their shoes, as many as 400,000 of their “bourgeois” urbanite victims were expelled from their homes and frog-marched, barefoot, into the countryside to work on state and collective farms. Unsurprisingly, urban dwellers who survived these terrors tended to hunker down and avoid drawing attention to themselves. Women ceased wearing makeup or heels or braiding their hair, and men adopted bland “proletarian haircuts.” Household items, from sinks to silks to pillows to children’s toys, were redesigned to look as bland and functional as possible. Even socks were jettisoned as remnants of benighted “old” feudalism … Mao finally reined in the Cultural Revolution Group [and] [t]he last remaining Red Guard units were disbanded by force in July 1968. In a turnabout their “bourgeois” victims might have enjoyed, had they still been alive to witness it, on December 22, 1968, Mao issued a decree sending urban students, many of them former Red Guards, into the countryside for “reeducation.” They were now forced to work the fields with their hands instead of “lazing about in the city.” … Mao’s Cultural Revolution, in the end, cost far fewer lives than earlier convulsions like the Great Leap Forward—the best current estimates of the death toll come out at around 1.5 to 2 million—but the impact on China’s material civilization and culture was devastating. In many ways, the country is still recovering from the trauma.

The madness of China spread to nearby Cambodia:

Even as it was calcifying at home, Mao’s Cultural Revolution spread beyond China’s borders into neighboring Cambodia, by way of a virulent, Red Guards–inspired Communist movement known as the Khmer Rouge or “Red Khmer” (Khmer is the language spoken by Cambodians) … The Khmer Rouge idea of Cultural Revolution entailed “stripping away, through terror and other means, the traditional bases, structures and forces which have guided an individual’s life,” from parental authority, religion, and royal tradition to even things such as “traditional songs and dances,” until “he is left an atomized, isolated individual unit; and then rebuilding him according to party doctrine and substituting a series of new values.” To achieve this, the Khmer Rouge would destroy everything that made up Cambodian tradition and civilization, which was all “anathema that must be destroyed.” … Whereas the Bolsheviks, and Mao’s Communists, had taken care to secure gold and cash reserves in the banks they nationalized, the mostly teenage thugs of the Khmer Rouge, after bursting into the Banque Khmer de Commerce, set fire to huge piles of Cambodian riels and threw the rest out the windows … No one knows for sure how many Cambodians died at the hands of the Khmer Rouge during their four-year reign of terror, but that the scale was genocidal is not in dispute. The tales of horror told by witnesses and refugees were so overwhelming that the Communist government of North Vietnam, which had helped arm the Khmer Rouge, invaded Cambodia largely out of mercy in December 1978 to put an end to Pol Pot’s murderous regime … The Communist government that now took over Cambodia on behalf of Hanoi, then known as the People’s Revolutionary Party of Kampuchea (PRPK), estimated that the Khmer Rouge had killed 3.1 million people, although most Western scholars think the figure is too high, reckoning the real number somewhere between 1 million and 2 million—which is still between one-seventh and one-third of the entire population … What was singular in Cambodia was the all-encompassing “year zero” ambition of the Khmer Rouge. Here Communism was reduced to its essentials, as a negation of everything existing, a war of the young on the old, a social leveling of society down to equality in abject poverty and misery. Pin Yathay, a Cambodian engineer whose family was wiped out by the Khmer Rouge before he escaped and staggered on foot across the mountains to Thailand, later recalled of life in “Democratic Kampuchea,” “There were no schools, no money, no communications, no books, no courts … [S] urveillance was constant and mutual … [W] e were warned to be vigilant and invited to denounce friends.” Because so many children “denounced their parents, simply in order to ‘purify’ them,” “adults became wary of talking freely in the presence of children.” At compulsory political meetings, adults were told that “the perfect revolutionary… should not experience any feeling, was forbidden to think about spouse and children, could not love.” … Unlike Lenin, Stalin, or Mao, Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge scarcely tried to justify their methods with happy talk about industrial progress, aside from vague chatter about (in Yathay’s words) the “perfect communist country” they were building. The coercion itself was the point, the reduction of free-willed humans to animals, enslaved by robotic, heavily armed children who had themselves been deprived of any kind of genuine education, human warmth, or feeling. Small wonder the North Vietnamese Communists intervened … Fortunately for the image of Communism, outside of Hanoi and Beijing, a few refugee camps in Thailand, and Cambodia itself, there were very few people who had genuine knowledge of what was happening in Cambodia between 1975 and 1979. Sydney Schanberg, the reporter best known for exposing what is now generally referred to as the “Cambodian genocide,” did not actually break the story until 1980 … In a rare Chinese admission of complicity, China’s ambassador to Cambodia, Zhang Jinfeng, admitted in an interview in 2010 that Beijing had sent aid to the Khmer Rouge, but that it consisted only of “scythes and hoes.” These were often the very weapons of choice used by Khmer Rouge thugs in rural beatings and executions.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll explore the final collapse of the Russian economy and China’s continued survival only by means of allowing some free market capitalism to act as a crutch to prop up its economic system.