The Distribution of Smallpox Vaccinations in the Early 1800’s

Controversies about federal vaccine policy go back to James Madison.

Today, to get the COVID vaccine, you get it (if you want it) for free in your local area. But what did people do to get vaccines back in the early 1800’s? Yes, they had vaccines back then (for smallpox). And how was the federal government involved? Yes, it was involved, but not without controversy.

Andrea Rusnock wrote a great article called “Catching Cowpox: The Early Spread of Smallpox Vaccination, 1798-1810, in the Bulletin of the History of Medicine, Vol. 81, No. 1 (Spring 2009) (John Hopkins University Press). In it, she writes:

Introduced by the English doctor Edward Jenner in his 1798 pamphlet An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of Variolae Vaccinae, vaccination was the procedure of infecting a healthy individual with cowpox [a virus similar to, but less virulent than, smallpox] in order to prevent a subsequent case of natural smallpox. Unlike other diseases, cowpox was deliberately spread from England by physicians, surgeons, and others, but not without difficulty. Cowpox, in contrast with smallpox and measles, did not travel well.

At the time, smallpox had become one of the leading viral killers worldwide.

In the county of Gloucestershire, England, Edward Jenner had noticed and recorded a few cases of milkmaids and farm laborers who became afflicted with cowpox and were later immune to smallpox. In 1796, Jenner took cowpox-infected lymph (a colorless fluid in the bloodstream) taken from a milkmaid and inserted it into a scratch made on the arm of a boy named James Phipps. Phipps then got a mild case of cowpox, and when he was later exposed to smallpox he showed no illness. This was a great innovation, but cows infected with cowpox were hard to find, so early vaccinators focused their efforts on methods of transporting human lymph (with cowpox in it) to others.

As Rusnock writes:

Lymph was distributed through private correspondence networks as well as through official channels. Some of these networks can be retraced through extant letters and artifacts, but most cannot. Individuals who wanted a supply of cowpox often tried many channels, because the chances that the cowpox would arrive ineffective were high … It was transported in three ways: in a dried state, in a fluid state, and by vaccinated individuals. The first method to be tried … involved sending a thread that had been soaked in cowpox lymph and then dried … Jenner’s thread proved effective … Threads were convenient because they were small, lightweight, and easily sent by post. But their failure rate was great, so early vaccinators tinkered with other techniques. In his 1801 pamphlet, Instructions for Vaccine Inoculation, Jenner recommended preserving dried cowpox lymph “between two plates of glass ... The virus, thus preserved ... may easily be restored to its fluid state by dissolving it in a small portion of cold water, taken up on the point of a lancet ...”

Cowpox could also be transmitted in a fluid state in which smallpox lymph was stored on the end of a lancet, but then it had to be used within two or three days before the lancet rusted and ruined its effectiveness. To avoid rusting, lancets were made of gold, silver, or platinum, but that increased its cost, so vaccinators later developed cheaper lancets made of quills and ivory pins.

Check out the shipping instruction for cowpox fluid:

In a letter to Jenner, [Jean] De Carro carefully described his successful shipping technique. First he saturated lint with cowpox lymph and then placed the lint between two pieces of glass, one concave, one flat. He then sealed it with oil. “To prevent the access of light,” De Carro continued, “I commonly fold it in a black paper, and when I was desired to send to Baghdad, I took the precaution of going to a wax-chandler’s, and surrounded the sealed-up glasses with so much wax as to make balls.

Thomas Jefferson wanted to be vaccinated, and so he wrote to Benjamin Waterhouse, a Harvard Medical School professor. Waterhouse tried twice to send cowpox lymph to Jefferson, but unfortunately both samples arrived inert. Undaunted, writes Rusnock:

Jefferson designed a new container: An inner chamber would hold the fluid lymph, while a surrounding chamber, filled with cool water, insulated the lymph from heat. Waterhouse adopted Jefferson’s method, but he continued to ship cowpox lymph using threads and glass as well. James Smith, in Baltimore, also faced the “almost insuperable difficulty of keeping the matter active” during the steamy months of July and August. In 1803, Smith started to preserve cowpox scabs, which he would later moisten with a drop of water prior to insertion. This method allowed Smith to maintain a supply of cowpox and to avoid the difficulties associated with transportation.

Did you experience some soreness when you got a vaccine recently? Well, check out the nastiness that accompanied smallpox vaccines back in the day.

As Rusnock writes:

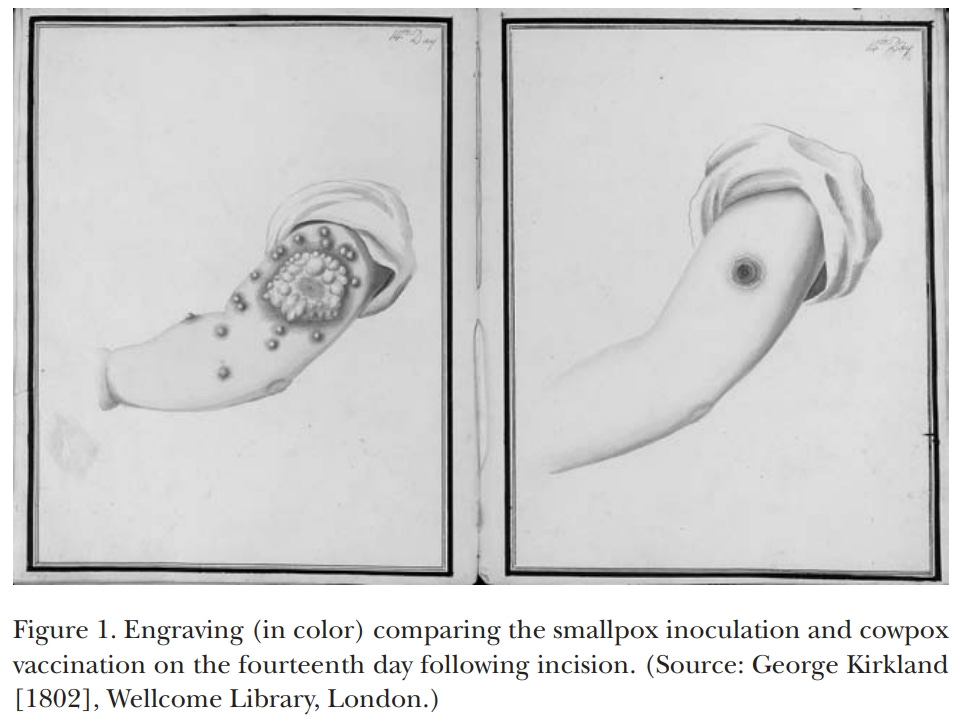

For physicians, surgeons, and other practitioners who had not directly witnessed vaccination, pamphlets and engravings provided invaluable guidance. Jenner’s Inquiry (1798) and his Instructions for Vaccine Inoculation (1801), along with other pamphlets such as C. R. Aikin’s A Concise View of All the Most Important Facts which have hitherto appeared concerning the Cow-Pox gave clear instructions and details concerning the method and course of vaccination … Other plates compared the lesions from inoculated and vaccinated patients, so that smallpox inoculators would know what to expect when they vaccinated their patients … [I]n the spring of 1801, [Benjamin] Waterhouse sent the engravings along with a copy of Aikin’s pamphlet to now-President Thomas Jefferson.

Once a shipment of cowpox vaccine arrived in a new location, it was generally passed along through arm-to-arm transfer, in which the vaccinator would puncture a lesion on someone who got the cowpox vaccine and remove lymph on the tip of the lancet, which would then be inserted into a small cut made on another person’s arm.

Back then, encouraging people to get the vaccine could be difficult. As Rusnock writes, “In Glasgow, parents had to put down a deposit of 1 shilling (1801) and later 2 shillings (1806) to be refunded only when the child was returned to the clinic. In Boston, Waterhouse resorted to paying parents to vaccinate their children in order to keep a supply of cowpox.”

Then, in the United States, as described in David Currie’s book The Constitution in Congress: The Jeffersonians (2001), on February 27, 1813, President James Madison signed the following statute into law:

[T]he President of the United States … is hereby authorized to appoint an agent to preserve the genuine vaccine matter, and to furnish the same to any citizen of the United States, whenever it may be applied for, through the medium of the post office …

As Currie explains, “Packages of vaccines dispatched by the agent, and letters to or from him on the subject of vaccination, were to ‘be carried out by the United States’ mail free of charge.’” Interestingly, congressional opposition prevented federal funds from being appropriated for the purpose of implementing this provision. Yet the statute itself, by allowing vaccine-related mail to be sent free of charge by federally-paid mail carriers, was indirectly funding this vaccine distribution program.

James Smith, a Baltimore physician, was appointed by Madison to be the first federal Vaccine Agent, and he requested that Congress expand the program. A select congressional committee recommended amending the statute to require the Vaccine Agent to furnish the vaccine to anyone who requested it free of charge, and also to pay the Vaccine Agent a salary with federal funds. But, as reported in the Annals of Congress (29 Annals at 719, 940, 1408, 1455, 1457), consideration of the bill was requested to be indefinitely postponed by Timothy Pickering of Massachusetts and Daniel Webster of New Hampshire, in light of “the doubt whether Congress could constitutionally appropriate money for such purposes.”

The Vaccine Agent subsequently renewed his request, and added that he should be paid a salary and also authorized to provide the vaccine for free to Army and Navy surgeons. Several Members of Congress said they had no objections to so authorizing the Army and Navy surgeons (thinking that such authority was clearly granted under the Constitution as part of the federal government’s authority to support a military), but they objected to extending that authority to providing vaccines to others, preferring instead to leave that to the states to administer is they so chose. The bill containing the Vaccine Agent’s requests was put to a vote, but it was defeated in the U.S. House of Representatives by a vote of 57-88.

The Vaccine Agent then made a different request, this time asking Congress to grant a charter of incorporation to a “National Vaccine Institution” that would be funded by private donations and charged with sending vaccines to anyone requesting them. A bill containing that proposal was introduced in the the Senate, but then tabled, and never to reappear, in part because of a government screwup.

In 1821, the Vaccine Agent Dr. Smith mistakenly sent smallpox scabs instead of a vaccine to someone in North Carolina, and several people died as a result. Members of Congress demanded repeal of the statute, and Congress did just that. President Madison had already fired the Vaccine Agent a few weeks before.

So the U.S. smallpox federal vaccine program of the early 1800’s wasn’t exactly as successful as Operation Warp Speed. Still, Representative Lewis Condict of New Jersey argued in 1822 that, while the Vaccine Agent program was in existence, it had saved between fifty and one hundred thousand people. Rusnock provides more detail relevant to that claim, writing that:

[L]and expeditions provided another path for the spread of cowpox [for purposes of vaccination against smallpox]. President Thomas Jefferson gave some cowpox lymph to Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to take on their explorations west of the Mississippi River. Antoine Saugrain, the only practicing physician in St. Louis when Louisiana was purchased by the United States from France in 1803, received some cowpox lymph from Lewis and Clark and began to vaccinate individuals free of charge, including native Americans. Saugrain’s free vaccination program established cowpox in the Mississippi valley roughly a decade after Jenner published his Inquiry. In his 1802 pamphlet, Waterhouse stated that he had “planted the true vaccine disease directly in the Province of Maine; in New Hampshire; in the state of Vermont, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, Virginia, South Carolina, Georgia, Kentucky, and Tennessee; and in every part of Massachusetts …. The physicians in the state of Pennsylvania, Delaware, North Carolina, and Maryland, were supplied from my stock, through Mr. Jefferson.”

And so vaccine policies remain controversial today. But who would have thought (without knowing this history) that there were vaccines at all back in the early 1800’s, and that some of the same arguments about federal vaccine policy being made today were also being made back in the early nineteenth century, when James Madison was President?