A Partial Summary of the Big Picture

Pulling together some of the main themes of the Big Picture over the last three years.

In this essay, I’ll take the opportunity to survey many of the topics we’ve previously explored on this Substack, and connect them together, in an effort to present in one place many of the more significant elements of the Big Picture we face as a nation today. I won’t go into the details of each of these inter-related trends here (those details are included in previously-posted entries that cover these topics more extensively), as my aim is to make lots of these connections in a single essay that can be read in a single sitting, so people might more clearly see how certain negative trends don’t just exist on their own, but rather reinforce the negative effects of yet other trends. So here goes.

A lack of teacher and administrator accountability in the educational system, and a breakdown in discipline — and the distractions to other students that breakdown causes — results in poor student performance, regardless of the amount of taxpayer money spent on education. The availability of unlimited federal loans allows colleges to raise tuition without improving educational results, and leaves more students with larger educational debt when (and if) they graduate, reducing their future financial prospects, and causing them to delay marriage and having children — unless they work for the government, in which case their student loans can be forgiven after ten years of minimum payments (even though government workers in general make more than their private sector counterparts). College faculty are overwhelmingly biased toward policies and candidates that support larger government programs, and most colleges have in place speech codes that suppress unpopular views, and so students graduate believing government should do even more to solve people’s problems. College racial preference systems in admissions have resulted, counter-productively, in fewer minority graduates. Almost half of all college students achieve no gains in critical thinking, complex reasoning, and writing skills, and when college graduates do find jobs, almost half of those jobs do not require a college degree. Today, better paying jobs require expensive college degrees because companies would be likely to face legal challenges based on “disparate impact” claims if they administered their own aptitude tests to high school graduates for hiring purposes, and so employers look to expensive college degrees as a proxy for aptitude. As a result, more middle-aged parents today are financially supporting their educational debt-ridden children and are less able to support their own aging parents.

Data show that poverty can be avoided if a person simply completes high school, works full time, and waits until age 21 before marrying and having children, yet fewer people follow those steps. (The official poverty rate itself is misleadingly high in that it doesn’t account for in kind government transfers, and if it did the poverty rate would be close to zero based on the value of the goods and services actually consumed by the poor.) Current welfare benefit programs pay more than a minimum wage job in most states, creating disincentives to work. As a report in the New York Times concluded, “Many men, in particular, have decided that low-wage work will not improve their lives, in part because deep changes in American society have made it easier for them to live without working. These changes include the availability of federal disability benefits; the decline of marriage, which means fewer men provide for children; and the rise of the Internet, which has reduced the isolation of unemployment.” Over time, people from poor families, especially those from single parent households, have come to have fewer prospects for upward mobility.

Over the last several decades, men have left the labor force in increasing percentages, regardless of their employment prospects, and their median income has dropped accordingly. Despite the better general health of today’s workforce, federal disability payments have grown as eligibility criteria have widened to include subjective criteria, namely “mood” and “musculoskeletal” disorders (which now constitute about half of all such payments), with increasing numbers of younger people on the disability rolls.

As Nicholas Eberstadt explains:

Although our nation has never been so rich, never have so many been living on so-called poverty benefits. Although health and longevity for young and middle-aged parents are vastly better than in earlier times, never have so many children been living as if orphaned, with just a mother, just a father, or sometimes just grandparents. Although our economy celebrated “full employment” on the eve of the pandemic, our work rate for prime-age American men mirrored levels from the tail end of the Great Depression. And although our national net worth has been soaring for decades, net worth for households in the bottom half was actually lower when the pandemic hit than when the Berlin Wall fell, 30 years earlier.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, one of the principal founders of the modern welfare state, believed that a dependence on welfare destroyed the human spirit. He stated the following in his January 4, 1935, Annual Message to Congress:

The lessons of history, confirmed by the evidence immediately before me, show conclusively that continued dependence upon relief induces a spiritual and moral disintegration fundamentally destructive to the national fibre. To dole out relief in this way is to administer a narcotic, a subtle destroyer of the human spirit. It is inimical to the dictates of sound policy. It is in violation of the traditions of America. Work must be found for able-bodied but destitute workers. The Federal Government must and shall quit this business of relief.

In her biography of Frances Perkins, The Woman Behind the New Deal: The Life of Frances Perkins, FDR’s Secretary of Labor and His Moral Conscience, Kirstin Downey writes:

By October the effort had expanded into an alphabet soup of relief agencies—the Federal Employment Relief Administration, or FERA; the Civil Works Administration or Program, known as CWA; and the Public Works Administration, or PWA. The programs contained relief features, but, because Roosevelt favored paid work rather than handouts, they involved creating jobs, so that people earned pay for accomplishing tasks. Roosevelt later explained that “to dole out relief … is to administer a narcotic, a subtle destroyer of the human spirit.”

And as another Franklin (Benjamin Franklin) wrote, “I am for doing good to the poor, but I differ in opinion of the means. I think the best way of doing good to the poor, is not making them easy in poverty, but leading or driving them out of it.” Contrary to popular belief, “From the earliest colonial days, local governments took responsibility for their poor. However, able-bodied men and women generally were not supported by the taxpayers unless they worked. They would sometimes be placed in group homes that provided them with food and shelter in exchange for labor. Only those who were too young, old, weak, or sick and who had no friends or family to help them were taken care of in idleness.”

Younger workers’ dropping out of the labor force today means there are fewer workers today paying for everyone’s ever-larger government benefits, which will increasingly go to older people in the years to come. At the same time, the birth rate is at historic lows generally, and especially among those with higher income and education levels, meaning there will be even fewer productive workers to pay for even more promised government benefits in the future, especially as members of each successive generation has shown they are less likely to enter the labor force than the previous generation. Part of the reason for the lower birth rate is that increased government benefits have led people to no longer come to expect their children to help provide for them in old age.

Larger entitlement programs and lower fertility rates mean that parents who are spending the resources to raise children are disproportionately contributing to the future entitlement program funding streams for others, making it more difficult to raise children just as more children are needed to sustain the growing entitlement system. As America’s debt burden looms, the younger generation will be facing much higher tax bills, both in total and as a share of their incomes, than their parents, unless the system is reformed. As younger people have to come to pay even more to support older people, younger people will be even less able to afford children of their own, and so they are likely to have fewer children, and the situation will worsen going forward. As Thomas Jefferson wrote, “The principle of spending money to be paid by posterity, under the name of funding, is but swindling futurity on a large scale.”

In the past the public debt as a percentage of gross domestic product generally rose as a result of having to conduct wars of a finite duration. But when those wars were over, the debt was paid off. More recently, public debt has risen as a result of having to pay for entitlement programs that are of indefinite duration and difficult to reduce over time.

The numbers show how far afield we’ve gone since the country’s founding. As President George Washington said in his Farewell Address:

As a very important source of strength and security, cherish public credit. One method of preserving it is to use it as sparingly as possible, avoiding occasions of expense by cultivating peace, but remembering also that timely disbursements to prepare for danger frequently prevent much greater disbursements to repel it, avoiding likewise the accumulation of debt, not only by shunning occasions of expense, but by vigorous exertion in time of peace to discharge the debts which unavoidable wars may have occasioned, not ungenerously throwing upon posterity the burden which we ourselves ought to bear. The execution of these maxims belongs to your representatives, but it is necessary that public opinion should co-operate.

The principal architect of the Constitution, James Madison, said in a speech to Congress, “There is not a more important and fundamental principle in legislation, than that the ways and means ought always to face the public engagements; that our appropriations should ever go hand in hand with our promises.” And as the first Treasury Secretary, Alexander Hamilton, wrote in his Report on Public Credit, “As on the one hand, the necessity for borrowing in particular emergencies cannot be doubted, so on the other, it is equally evident that to be able to borrow upon good terms, it is essential that the credit of a nation should be well established.”

With the greater availability of government benefits, people have less incentive to enjoy the economic benefits of marriage, and so fewer people marry, especially those with a high school education or less. As fewer people marry, more children are born into single-parent homes, in which parental supervision is cut in half, resulting in generally negative outcomes for children regarding educational performance and self-control. Marriage also reduces poverty. Married couples have higher incomes than unmarried people, as they benefit from economies of scale, the division of labor, and the incentive to invest in their children’s future (if they have children). Unmarried men, without the responsibility of a family to provide for, have tended to work less over time, make less money, or drop out of the labor force entirely. But fewer people are getting married.

Federal taxes have long been steeply progressive, even compared to other industrialized countries. Just to balance the yearly federal budget through tax increases on the highest two tax brackets alone, taxes would have to be raised to well over 100 percent (that is, to mathematically impossible levels). Even if every penny of income earned by millionaires in the U.S. was collected in taxes, it wouldn’t be enough to close the U.S. deficit. According to the Joint Committee on Taxation, millionaires had an estimated $3.312 trillion in income in 2024 and were expected to pay a combined $1.006 trillion in federal taxes. That would leave $2.3 trillion more to be taken from them — but that is only the amount that the national debt increased during fiscal year 2024 alone.

While greater happiness tends to be correlated with being married, having children, being religious, and being more supportive of free markets, fewer people today are experiencing those things.

The Founding generation of Americans believed that the success of self-government would only be possible under a constitutional system of limited government, in which individual Americans, for the most part, could be trusted to govern their own behavior. In particular, as Charles Murray has written, at the founding of the country, “four aspects of American life were so completely accepted as essential that, for practical purposes, you would be hard put to find an eighteenth-century founder or a nineteenth-century commentator who dissented from any of them. Two of them are virtues in themselves – industriousness and honesty – and two of them refer to institutions through which right behavior is nurtured – marriage and religion.” It so happens these virtues are also associated with greater happiness. But they are waning.

As the famed French observer of American culture Alexis de Tocqueville wrote back in 1840, commenting on how the growth in government regulation threatened to result in trained hopelessness:

Above this race of men stands an immense and tutelary power, which takes upon itself alone to secure their gratifications and to watch over their fate. That power is absolute, minute, regular, provident, and mild. It would be like the authority of a parent if, like that authority, its object was to prepare men for manhood; but it seeks, on the contrary, to keep them in perpetual childhood … For their happiness such a government willingly labors, but it chooses to be the sole agent and the only arbiter of that happiness; it provides for their security, foresees and supplies their necessities, facilitates their pleasures, manages their principal concerns, directs their industry, regulates the descent of property, and subdivides their inheritances: what remains, but to spare them all the care of thinking and all the trouble of living? Thus it every day renders the exercise of the free agency of man less useful and less frequent; it circumscribes the will within a narrower range and gradually robs a man of all the uses of himself. The principle of equality has prepared men for these things; it has predisposed men to endure them and often to look on them as benefits. After having thus successively taken each member of the community in its powerful grasp and fashioned him at will, the supreme power then extends its arm over the whole community. It covers the surface of society with a network of small complicated rules, minute and uniform, through which the most original minds and the most energetic characters cannot penetrate, to rise above the crowd. The will of man is not shattered, but softened, bent, and guided; men are seldom forced by it to act, but they are constantly restrained from acting. Such a power does not destroy, but it prevents existence; it does not tyrannize, but it compresses, enervates, extinguishes, and stupefies a people, till each nation is reduced to nothing better than a flock of timid and industrious animals, of which the government is the shepherd.

The incentive structures created by this dynamic operate on human beings and their own human nature in ways that transcend race and other immutable traits. As Martin Luther King, Jr., observed, the key is to apply those rules that liberate the potential of all people to all people, regardless of race or other immutable traits: “When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” The psychological value of earned success has been notably described by Frederick Douglass, who was himself a former slave. As described in Timothy Sandefur’s “Frederick Douglass: Self-Made Man”:

Knowing he could reap the rewards of his own toil ‘placed me in a state of independence,' [Douglass] wrote, and his first day of freely chosen labor seemed to him ‘the real starting point of something like a new existence … The fifth day after my arrival I put on the clothes of a common laborer, and went upon the wharves in search of work. On my way down Union street I saw a large pile of coal in front of the house of Rev. Ephraim Peabody, the Unitarian minister. I went to the kitchen-door and asked the privilege of bringing in and putting away this coal. ‘What will you charge?’ said the lady. ‘I will leave that to you, madam.’ ‘You may put it away,’ she said. I was not long in accomplishing the job, when the dear lady put into my hand two silver half-dollars. To understand the emotion which swelled my heart as I clasped this money, realizing that I had no master who could take it from me -- that it was mine -- that my hands were my own, and could earn more of the precious coin … I was not only a freeman but a free-working man, and no master Hugh stood ready at the end of the week to seize my hard earnings.’ … Thus, Douglass viewed economic freedom as more than an incentive: it was the source and symbol of personal liberation. He made this idea explicit in a later speech: ‘What is freedom? It is the right to choose one’s own employment.’

Frederick Douglass also said in a speech in 1865:

Everybody has asked the question, and they learned to ask it early of the abolitionists, ‘What shall we do with the Negro?’ I have had but one answer from the beginning. Do nothing with us! Your doing with us has already played the mischief with us. Do nothing with us! If the apples will not remain on the tree of their own strength, if they are wormeaten at the core, if they are early ripe and disposed to fall, let them fall! I am not for tying or fastening them on the tree in any way, except by nature’s plan, and if they will not stay there, let them fall. And if the Negro cannot stand on his own legs, let him fall also. All I ask is, give him a chance to stand on his own legs!

Douglass said of newly freed black slaves, “What they needed was more liberty to earn a living and keep the fruits of their labor, not paternalism, control, and oversight by a government dominated by whites.” Although Douglass rarely addressed socialism explicitly, in the words of his first biographer, Frederic May Holland, whose 1891 book was prepared with Douglass’s active involvement, “The present views of Mr. Douglass” were that while “our existing system of free labor in keen competition has many defects,” it had “succeeded much better than any other, not only in increasing the general wealth, to the benefit of even the poorest, but in developing individual energy, intelligence, industry, economy, foresight, perseverance, and self-control,” and that a free market system was simply “the only system of labor which a lover of liberty can favor consistently.” Douglass wrote that “My cause, first, midst, last, and always, was and is that of the black man; not because he is black, but because he is a man.” As Timothy Sandefur has written:

Pride in one’s own race was in his eyes no less ‘ridiculous’ than hatred of other races. The values he emphasized were good for the individual, and his hope was that Americans would learn to focus on the quality of each man and woman specifically, rather than on skin color, and thereby make racism obsolete … Douglass believed the nation’s heart was the principle of equality articulated in the Declaration of Independence, and that to assert the contrary was to concede the claims of white supremacists.

In 1930, a group of Southern writers extolled the alleged virtues of the Old South, with its rejection of industrialization and commercialization, in a collection of essays entitled “I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition,” which stated in its introduction:

All the articles [herein] bear in the same sense upon the book's title-subject: all tend to support a Southern way of life against what may be called the American or prevailing way; and all as much as agree that the best terms in which to represent the distinction are contained in the phrase, Agrarian versus Industrial. ... [A]n agrarian regime will be secured readily enough where the superfluous industries are not allowed to rise against it. The theory of agrarianism is that the culture of the soil is the best and most sensitive of vocations, and that therefore it should have the economic preference and enlist the maximum number of workers.

Contrary to this, Booker T. Washington, a former slave who became the first head of the Tuskegee Institute, embraced the Industrial Revolution and the Puritan work ethic, stating in an 1895 address to the International Exposition in Atlanta:

[T]he opportunity here afforded will awaken among us a new era of industrial progress. Ignorant and inexperienced, it is not strange that in the first years of our new life we began at the top instead of at the bottom; that a seat in Congress or the state legislature was more sought than real estate or industrial skill; that the political convention or stump speaking had more attractions than starting a daily farm or truck garden … To those of my race who depend on bettering their condition in a foreign land or who underestimate the importance of cultivating friendly relations with the Southern white man, who is their next door neighbor, I would say: “Cast down your bucket where you are”-cast it down in making friends in every manly way of the people of all races by whom we are surrounded. Cast it down in agriculture, mechanics, in commerce, in domestic service, and in the professions. And in this connection it is well to bear in mind that whatever other sins the South may be called to bear, when it comes to business, pure and simple, it is in the South that the Negro is given a man’s chance in the commercial world, and in nothing is this Exposition more eloquent than in emphasizing this chance. Our greatest danger is that in the great leap from slavery to freedom we may overlook the fact that the masses of us are to live by the productions of our hands, and fail to keep in mind that we shall prosper in proportion as we learn to dignify and glorify common labour, and put brains and skill into the common occupations of life; shall prosper in proportion as we learn to draw the line between the superficial and the substantial, the ornamental gewgaws of life and the useful. No race can prosper till it learns that there is as much dignity in tilling a field as in writing a poem. It is at the bottom of life we must begin, and not at the top. Nor should we permit our grievances to overshadow our opportunities … There is no defense or security for any of us except in the highest intelligence and development of all. If anywhere there are efforts tending to curtail the fullest growth of the Negro, let these efforts be turned into stimulating, encouraging. and making him the most useful and intelligent citizen. Effort or means so invested will pay a thousand per cent interest. These efforts will be twice blessed--”blessing him that gives and him that takes.” … Nearly sixteen millions of hands will aid you in pulling the load upward. or they will pull against you the load downward. We shall constitute one-third and more of the ignorance and crime of the South, or one-third its intelligence and progress; we shall contribute one-third to the business and industrial prosperity of the South, or we shall prove a veritable body of death. stagnating, depressing, retarding every effort to advance the body politic.

Booker T. Washington also explained that the best way to dispel self-doubt as a minority is through objective performance:

But race-based preference policies, and entitlement benefits programs more generally, have since become prevalent, with perverse results. As some theorists have posited:

A partially self-interested left-wing party may implement (entrenchment) policies reducing the income of its own constituency, the lower class, in order to consolidate its future political power. Such policies increase the net gain that low-skill agents obtain from income redistribution, which only the Left (but not the Right) can credibly commit to provide, and therefore may help offsetting a potential future aggregate ideological shock averse to the left-wing party.

A modern historian, following a survey of collapsed societies throughout history, concluded:

Two general factors can make such a society liable to collapse. First, as the marginal return on investment in complexity declines, a society invests ever more heavily in a strategy that yields proportionately less. Excess productive capacity and accumulated surpluses may be allocated to current operating needs. When major stress surges (major adversities) arise there is little or no reserve with which they may be countered. Stress surges must be dealt with out of the current operating budget. This often proves ineffectual.

In essence, as societies grow they become increasingly complex, adding layer upon layer of institutions, regulations, and customs to deal with challenges. Over time, these layers grow increasingly rigid and consume more and more of the society’s resources, making them increasingly hard to change because each layer of complexity represents some group or other’s livelihood or claim on power, which they will ferociously resist reforming, while everyone else, with less to gain or lose with reform, are less inclined to push for it. Eventually, these increasingly complex societies devote almost all their resources to maintaining these institutions and have very little reserve left to deal with the unexpected. The result is that challenges these societies would have previously weathered easily are now sufficient to bring them to an end. Whether the United States continues to follow that trajectory remains to be seen.

George Washington and Thomas Jefferson wrote of the importance of knowledge in a democracy. Washington wrote, “Knowledge is, in every country, the surest basis of public happiness … In proportion as the structure of a government gives force to public opinion, it is essential that public opinion should be enlightened.” And as Thomas Jefferson reminded us, “Knowledge is power … If a nation expects to be ignorant – and free – in a state of civilization, it expects what never was and never will be.”

James Madison wrote of the inherent connection between free speech, learning, and liberty, writing:

What spectacle can be more edifying or more seasonable, than that of Liberty and Learning, each leaning on the other for their mutual and surest support … A popular Government without popular information, or the means of acquiring it, is but a Prologue to a Farce or a Tragedy, or perhaps both ... And a people who mean to be their own Governors, must arm themselves with the power which knowledge gives.

John Adams wrote specifically of his concern for young people in a democracy, writing that “It should be your care, therefore, and mine, to elevate the minds of our children and exalt their courage … If we suffer their minds to grovel and creep in infancy, they will grovel all their lives.”

Alice Dreger urges activist students and professors to “Carpe datum” (“Seize the data”) and contends that “Evidence really is an ethical issue, the most important ethical issue in a modern democracy. If you want justice, you must work for truth. And if you want to work for truth, you must do a little more than wish for justice.”

Locus of control – the concept in personality psychology that describes the degree to which people believe that they have control over the outcome of events in their lives (an “internal” locus of control), as opposed to believing their lives are controlled by external forces beyond their own control (an “external” locus of control) -- is understood as being learned, not inherited. Consequently, expanding people’s internal locus of control should be the focus of public policy such that policymakers ask whether any given policy proposal will tend to inculcate an internal, rather than an external, locus of control in the individuals affected by the policy. Locus of control may also be a better metric by which to judge policies because it focuses more on maximizing the means of happiness rather than trying to maximize individual things that are merely associated with happiness. Identity politics combined with arguments of victimization will tend to inculcate a more external locus of control among people, which is associated with unhappiness and reductions in well-being. As Booker T. Washington wrote, “The persons who accomplish the most in this world … are those who are constantly seeing and appreciating the bright side as well as the dark side of life.” And the solutions called for by proponents of such identity politics impose restrictions on others that will tend to give those others a more external sense of their own locus of control. And while a minimal social safety net might encourage an internal locus of control by preventing crippling poverty for those who can’t do for themselves, an overly generous social safety net will encourage dependence and foster an external locus of control.

Harvard professor Orlando Patterson edited a book titled “The Cultural Matrix: Understanding Black Youth,” which included a chapter titled “’I Do Me’: Young Black Men and the Struggle to Resist the Street,” by Peter Rosenblatt, Kathryn Edin, and Queenie Zhu, which examined through interviews how young blacks managed to avoid involvement in negative and criminal activities present in their neighborhoods. The main strategy reflects their association with an internal locus of control. As they wrote:

Turning away from the street often leads these young men to adopt a strong code of self-reliance, which several describe with the expression “I do me.” I do me is about controlling what you are able to control and not worrying about the rest … Gary is an old soul at twenty-three. He values what he refers to as the “old school upbringing,” which preaches respect and hard work, and laments what he sees as the decline of these values among youth of his generation … [M]any who resist the street espouse an ideology of “I do me,” which involves focusing on one’s own goals without reference to the reactions of others and, most importantly, espouses the idea that a young man should not have to rely on anyone else … [M]any young men deploy the “I do me” ethos as they navigate a different path. Despite the sharp structural obstacles they face, these youth believe that this ethos, and their determination to abide by its dictates, sets them apart from more delinquent peers.

Researchers have even run several studies they say:

confirmed our conceptualization of TIV [Tendency for Interpersonal Victimhood] and the psychometric properties of its scale. [Our studies] indicated that the TIV scale is best conceptualized as a hierarchical model with four method factors, representing the four dimensions of TIV; i.e., the need for recognition, moral elitism, lack of empathy, and rumination [which refers to a focus of attention on the symptoms of one's distress, and its possible causes and consequences rather than its possible solutions] … Behaviorally, high-TIV individuals were less willing to forgive others after an offense, and more likely to seek revenge rather than avoidance and behave in a revengeful manner … The clinical literature on victimhood may explain how moral elitism, lack of empathy and the desire for revenge can manifest simultaneously among high-TIV individuals, and thus enable them to feel morally superior even though they exhibit aggression … From a motivational point of view, TIV seems to offer anxiously attached individuals an effective framework for their insecure relations that involve gaining others' attention, recognition, and compassion, and at the same time experiencing and expressing negative feelings.

As the study was described in Psychology Today:

The researchers developed a Victim Signaling Scale, ranging from 1 = not at all to 5 = always. It asks how often people engage in certain activities. These include: “Disclosed that I don’t feel accepted in society because of my identity.” And “Expressed how people like me are underrepresented in the media and leadership.” They found that Victim Signaling scores highly correlated with dark triad scores (r = .35). This association held after controlling for gender, ethnicity, income, and other factors that might make people vulnerable to mistreatment. Participants also completed a questionnaire that measured Virtue Signaling. They rated the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with statements about moral traits like being fair, compassionate, and honest. A sample statement is “I often buy products that communicate the fact that I have these characteristics.” They also found that Virtue Signaling was significantly correlated with dark triad scores (r = .18). They replicated this association in a follow-up study. This time they used a different, more robust, dark triad scale. They then found a stronger correlation between the dark triad traits and victim signaling (r = .52). The researchers also found that victim signaling negatively correlated (r = -.38) with Honesty-Humility. This is a personality measure of sincerity, fairness, greed avoidance, and modesty. This suggests that victim signalers may be greedier and less honest than those who do not signal victimhood. Beyond measuring responses to questionnaires, they also had participants play a game. Basically, it was a coin flip game in which participants could win money if they won. Researchers rigged the game so that participants could easily cheat. Participants could claim they won even if they didn’t, and thus obtain more money. Victim signalers were more likely to cheat in this game. The researchers again found that these results held after controlling for ethnicity, gender, income, and other factors. Regardless of personal characteristics, those who scored higher on dark triad traits were more likely to be victim signalers. And may be more likely to deceive others for material gain. The researchers then ran a study testing whether people who score highly on victim signaling were more likely to exaggerate reports of mistreatment from a colleague to gain an advantage over them. Participants were told to imagine they worked with another intern. And that they were competing to land a job. Participants were told, “You keep noticing little things about the way the intern talks to you. You get the feeling the other intern may have no respect for your suggestions at all. To your face, the intern is friendly, but something feels off to you.” Then participants engaged in the feedback performance of the intern. Then they completed the Victim Signaling scale. Victim signalers were more likely to exaggerate the negative qualities of their competitor. They were more likely to agree that the intern “Made demeaning or derogatory remarks,” or “Put you down in front of coworkers.” Nothing in the description of their colleague indicated that they performed these actions. But victim signalers were more likely to report that they did. As the authors note, real victims exist. And they have no intention of deceiving or taking advantage of others. Still, alongside victims, there are social predators among us. In whatever milieu they find themselves in, they will enact the strategies that maximize the rewards of material resources, sex, or prestige. People with dark triad traits will tailor their strategies to obtain these benefits, depending on their social environments. Today, those with dark triad traits might find that the best way to extract rewards is by making a public spectacle of their victimhood and virtue.

Sadly, the Smithsonian’s National African-American History Museum advocated on its website (since removed) that being on time, self-reliance, grammatical rules for the English language, avoidance of conflict and intimacy, the scientific method, and rugged individualism are somehow distinctive markers of “whiteness,” a “critical theory” analysis that is itself racist in the sense it implies rational thinking is somehow “white.” (One of the other authors highlighted on the National African-American History Museum’s website, Robin DiAngelo, herself states in her book White Fragility that “two key Western ideologies: individualism and objectivity” – where she states “individualism holds that we are each unique and stand apart from others, even those within our social groups” and “[o]bjectivity tells us that it is possible to be free of all bias” -- are barriers to understanding instead of keys to understanding.

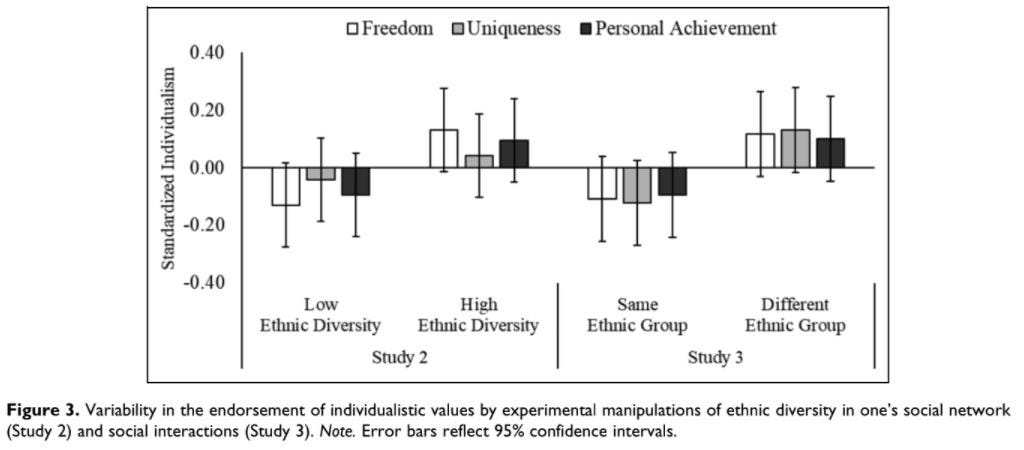

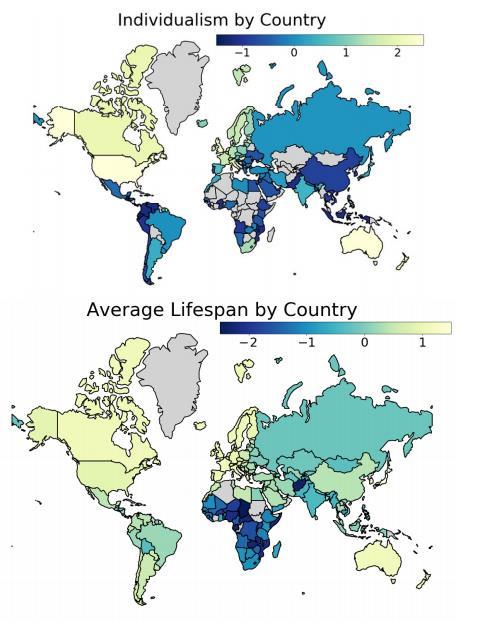

Researchers have found that greater racial and ethnic diversity within one’s social network tends to increase one’s adherence to the values of individualism, including individual autonomy and a greater preference for uniqueness, indicating that as America becomes more racially and ethnically diverse, its people will come to value individualism more, and loyalty to their racially and ethnically-defined in-group less, as interethnic contact involves weakened in-group boundaries. As the researchers reported:

In three studies, across different levels of measurement and analysis, we find converging evidence that ethnic diversity accompanies individualistic relational structures and increases the endorsement of individualistic values. Historical rates of ethnic diversity across different U.S. regions reveal this association (Study 1), as do individual-level reports of interethnic contact (Studies 2 and 3). The results of the forecasting model in Study 1 suggest that the trend toward increasing individualism will likely continue over the next several decades, assuming continuing growth in ethnic diversity … That is, future increases in ethnic diversity will likely be accompanied by an increasing societal emphasis on individualistic dimensions—for example, individual autonomy and a greater preference for uniqueness.

But proponents of racial and group identity politics don’t want that to happen.

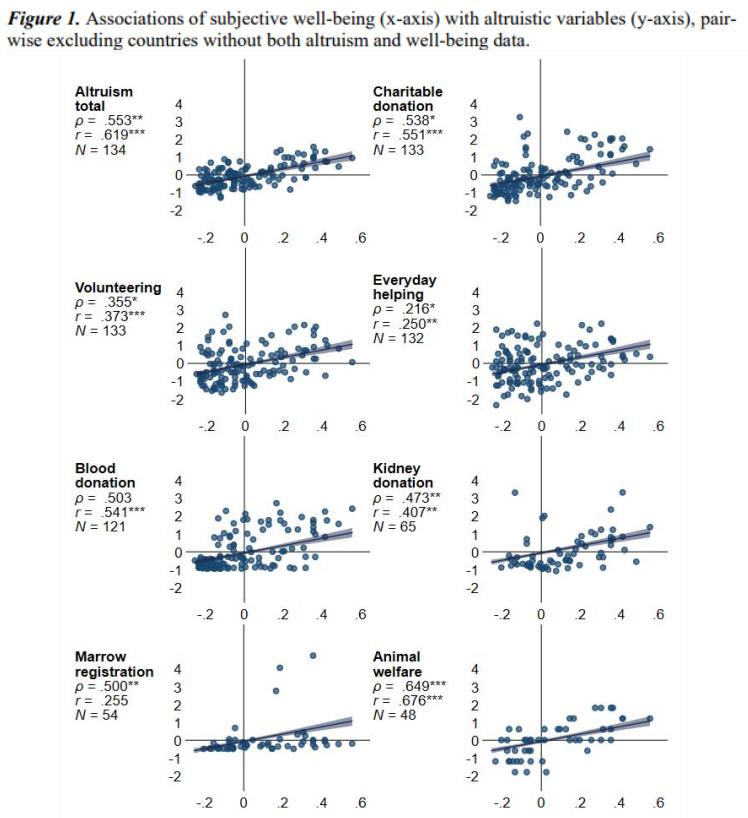

Researchers have also found that individualism is associated with both well-being and altruism. As one of the researchers described the results in the New York Times:

The United States is notable for its individualism. The results of several large surveys assessing the values held by the people of various nations consistently rank the United States as the world’s most individualist country. Individualism, as defined by behavioral scientists, means valuing autonomy, self-expression and the pursuit of personal goals rather than prioritizing the interests of the group … But new research suggests the opposite: When comparing countries, my colleagues and I found that greater levels of individualism were linked to more generosity — not less — as we detail in a forthcoming article in the journal Psychological Science. For our research, we gathered data from 152 countries concerning seven distinct forms of altruism and generosity. The seven forms included three responses to survey questions administered by Gallup about giving money to charity, volunteering and helping strangers, and four pieces of objective data: per capita donations of blood, bone marrow and organs, and the humane treatment of nonhuman animals (as gauged by the Animal Protection Index). We found that countries that scored highly on one form of altruism tended to score highly on the others, too, suggesting that broad cultural factors were at play. When we looked for factors that were associated with altruism across nations, two in particular stood out: various measures of “flourishing” (including subjectively reported well-being and objective metrics of prosperity, literacy and longevity) and individualism. The fact that countries in which people are flourishing are also those in which people engage in greater altruism is in keeping with earlier research showing that people who report high levels of personal well-being tend to engage in more positive, generous social behaviors. That individualism was closely associated with altruism was more surprising. But even after statistically controlling for wealth, health, education and other variables, we found that in more individualist countries like the Netherlands, Bhutan and the United States, people were more altruistic across our seven indicators than were people in more collectivist cultures — even wealthy ones — like Ukraine, Croatia and China. On average, people in more individualist countries donate more money, more blood, more bone marrow and more organs. They more often help others in need and treat nonhuman animals more humanely. If individualism were equivalent to selfishness, none of this would make sense.

Other researchers from five different universities found that “Our empirical results, which hold with three different measures of individualism, show that individualism is indeed associated with higher levels of charitable giving.”

The Founding generation believed altering the course of a society was difficult. As they wrote in the Declaration of Independence, “all experience hath shewn that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed.” The danger is that the slow but steady growth in government regulation since then may have gone on for so long now that it has gone largely unnoticed or under-appreciated, and made the need for change even less evident, even as the need for change has become more urgent. But perhaps the recent availability to more people of many more sources of information has begun to change things for the better.

Philosopher Bertrand Russell was asked in 1959 how he might summarize what he’d learned in life to people living 1,000 years from now. He said:

I should like to say two things, one intellectual and one moral. The intellectual thing I would want to say to them is this. When you are studying any matter or considering any philosophy, ask yourself only what are the facts and what is the truth that the facts bear out. Never let yourself be diverted either by what you wish to believe or by what you think would have beneficent social effects if it were believed. Look only and only and solely to what are the facts … The moral thing I should wish to say to them is very simple. I should say love is wise, hatred is foolish. In this world, which is getting more and more closely interconnected, we have to learn to tolerate each other. We have to learn to put up with the fact that some people say things that we don’t like. We can only live together in that way. And if we are to live together and not die together, we must learn a kind of charity and a kind of tolerance which is absolutely vital to the continuation of human life on this planet.

Finally, although many current trends are concerning, I’m optimistic about the future –- as long as people can receive, and are open to receiving, both factual and contextual information about the past and present.

And on a lighter note, the next series of essays will explore the science of fun.

Paul, Wow, a treatise all by itself. Your work over the past few years has greatly impacted my thinking on so many topics. This piece pulling it all together is appreciated -- the old forest/trees analogy holds. Thanks for all the time and effort you have put into this -- amazing content really.