The American Health Care System – Part 3

More evidence of dysfunction in the American health care system.

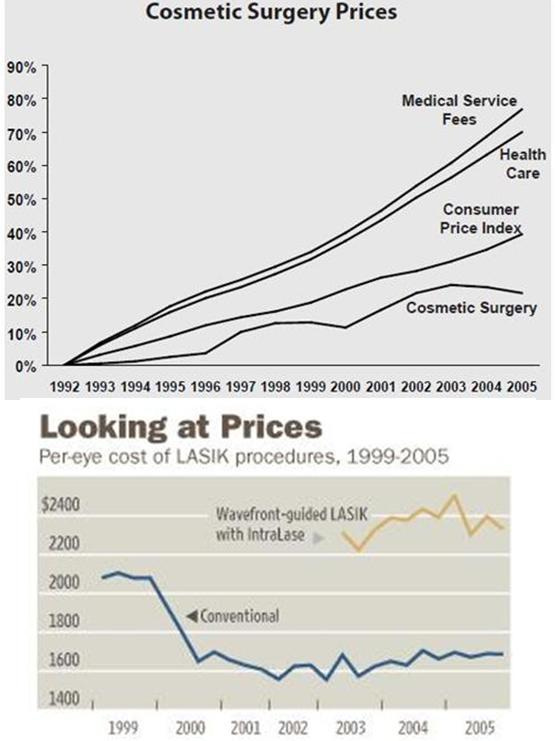

One way to see the difference between medical market systems in which health care providers compete for health care consumers who have to pay for most or all of the costs of the medical care provided, and medical provision systems in which health care providers are reimbursed by health insurance programs such that consumers don’t see the true costs of the medical care, is to compare their cost trajectories.

Mark Perry at the American Enterprise Institute does that:

Between 1998 and 2021 prices for “Medical Care Services” in the US (as measured by the BLS’s CPI for Medical Care Services) more than doubled (+132.2% increase) while the CPI for “Hospital and Related Services” (data here) more than tripled (+230.4% increase), see the bottom two rows of the table above. Those increases in the costs of medical-related services compared to only a 66.2% increase in overall consumer prices over that period (BLS data here). On an annual basis, the costs of medical care services in the US have increased 3.6% per year since 1998 and the cost of hospital services increased annually by 5.1%. In contrast, overall inflation averaged only 2.1% annually over that period. The only consumer product or service that has increased more than medical care services and just slightly less than hospital costs over the last several decades is college tuition and fees, which have increased nearly 5.0% annually since 1998 for four-year public universities.

One of the reasons that the costs of medical care services in the US have increased more than twice as much as general consumer prices since 1998 is that a large and increasing share of medical costs are paid by third parties (private health insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, Department of Veterans Affairs, etc.) and only a small and shrinking percentage of health care costs are paid out-of-pocket by consumers. According to government data, almost half (47.1%) of health care expenditures in 1960 were paid by consumers out-of-pocket, and by 2020 (most recent year available) that share of expenditures has fallen to only 9.4% (see chart above). It’s no big surprise that overall health care costs have continued to rise over time as the share of third-party payments has risen to more than 90% and the out-of-pocket share has fallen below 10%. Consumers of health care have significantly reduced incentives to monitor prices and be cost-conscious buyers of medical and hospital services when they pay less than $1 themselves out of every $10 spent, and the incentives of medical care providers to hold costs down are greatly reduced knowing that their customers aren’t paying out-of-pocket and aren’t price sensitive. How would the market for medical services operate differently if prices were transparent and consumers were paying out-of-pocket for medical procedures in a competitive market? Well, we can look to the $14.6 billion US market for elective cosmetic surgery for some answers. Every year since 1997, the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery has issued an annual report on aesthetic procedures in the US (both surgical and nonsurgical) that includes the number of procedures, the average cost per procedure (starting in 1998), the total spending per procedure, and the age and gender distribution for each procedure. The 2021 report was released in April and is available here. The table [below] displays the 16 cosmetic procedures that were available and reported in both 1998 and 2021, the average prices for those procedures in each year (in current dollars), the number of each of those procedures performed in those two years, and the percent increase in the average price for each procedure between 1998 and 2021. … The unweighted average price increase between 1998 and 2021 for the 16 aesthetic procedures displayed above was 31.3%, which is less than half of the 66.2% increase in consumer prices in general over the last 23 years … And most importantly, none of the 16 aesthetic procedures in the table above have increased in price by anywhere close to the 132% increase in the price of medical care services or the 230% increase in hospital services since 1998.

Because cosmetic surgery is not generally part of a mandated insurance regime, the rate of cosmetic surgery price inflation is dramatically lower than that for other health care. The LASIK eye surgery process, for example, which is not covered by insurance, has gotten better and cheaper over time.

Regarding the effect of transparency of pricing to lower costs, As James Capretta writes:

Turquoise Health, an industry leader in the collection and analysis of health care pricing data, has recently produced a preliminary examination of the effects of the government’s transparency rules on market results. The findings are interesting and mostly encouraging … [S]tarting in July of this year [2024] and then again in January 2025, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) will begin enforcing tighter restrictions on both the content and formatting of disclosures. In general terms, hospitals must now post online all relevant pricing data (including negotiated rates with payers) for both inpatient and outpatient services in formats that allow for ready capture and assessment by data technology companies. Further, insurers must do likewise for the rates they have agreed to pay to all providers of services. Finally, consumers paying cash for services have the right to an advance estimate of their expected charges. In theory, these rules are expansive enough to bring pricing data into the market that affects the entirety of most patient bills. The pace of rule adjustments might even accelerate starting next year. The original Trump administration was bullish on transparency and a return to its aggressive posture is to be expected when the second Trump administration begins in January. The author of the Turquoise report examined pricing trends from December 2021 through June 2024 for 37 hospital billing codes across 234 facilities located in the 10 largest US metropolitan areas … The main finding was that in most markets, there was convergence between high and low pricing over time even as the overall trends were modestly downward. In other words, there was a tendency for the highest priced providers to moderate their pricing and move closer to the median, and the lowest-priced providers to move in the opposite direction. After adjusting for inflation, the highest-priced providers (those above the 75th percentile in absolute price levels) posted negotiated charges that declined in real terms (after adjusting for inflation) at an average annual rate of 6.3 percent. At the same time, the lowest-priced facilities (below the 25th percentile) pushed their inflation-adjusted prices up at an average annual rate of 3.4 percent. The middle of the market (above the 25th percentile and below the 75th) reduced their prices for these services modestly, at an average annual rate of 1.1 percent … Further study is needed to determine the overall effect on total costs paid by insurers and patients. The Turquoise study also highlights other interesting details [such as] in some markets (about 17 percent of the examined service categories), the pricing did not converge over time. In these cases, the collected data show pricing drops across all examined facilities … Overall, the study validates the policy decision to force greater transparency on the market as there is a clear indication that price disclosure can help bring more discipline and balance to an unruly and still very arbitrary market. It also points to what should be the focus going forward, which is helping consumers reduce what they pay for care. Employers sponsoring health coverage will not lead the transformation the market needs because they are too risk-averse. Individual patients, however, may be more willing to break free from past practice and migrate to providers willing to charge much less for their services. It is time to give them the tools to bring this kind of disruption to a still grossly overpriced market.

A comprehensive review in The Journal of the American Medical Association shows there were two areas where the United States is significantly different from other countries regarding health care: Americans pay substantially higher prices for medical services, including hospitalization, doctors’ visits and prescription drugs; and America’s complex payment system causes those in the U.S. to spend far more on administrative costs.

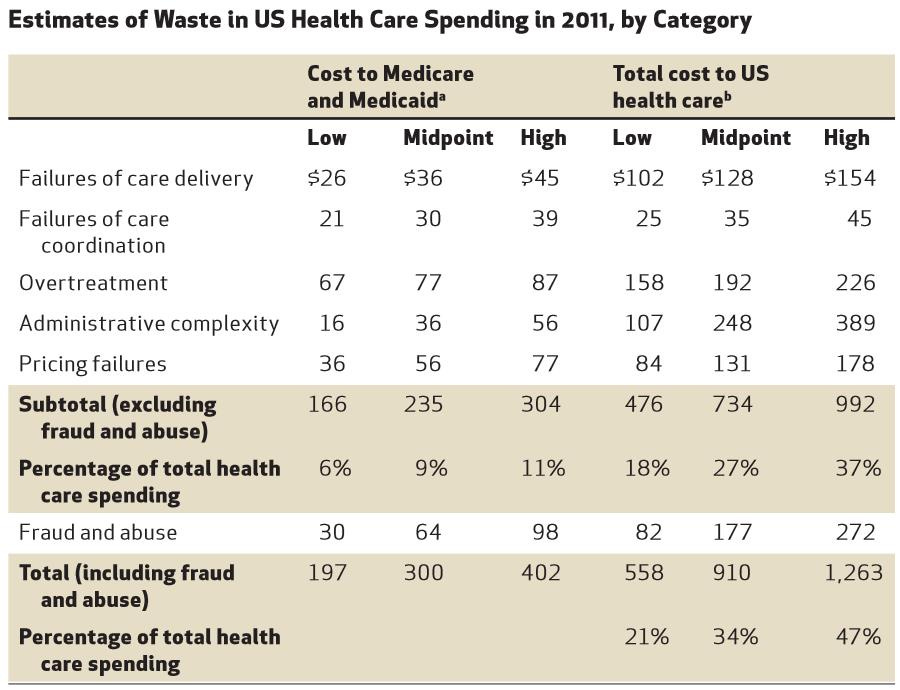

Data compiled by the Institute for Medicine in 2012 shows that as much as $750 billion in health care spending is wasted every year.

Other analyses conclude that about one-third of health care spending is wasted in one way or another, including through overpricing failures due to a lack of price competition.

And over 30 percent of health care costs go to administrative expenses instead of patient care.

A 2019 study, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, found that roughly 20 percent to 25 percent of American health care spending is wasteful.

Consequently, growth in health care costs has not been accompanied by a commensurate growth in the productivity of the health care labor force similar to the gains seen in other industries.

The Affordable Care Act (Obamacare), as with any statute that runs into many thousands of pages, not all of which was reviewed by any one person, there will likely be large unintended consequences. A study by Harvard and the University of Texas-Austin researchers found that the rules under the Affordable Care Act penalize high-quality coverage for the sick, reward insurers who cut coverage for the sick, and leave patients unable to obtain adequate insurance. The researchers estimate a patient, for example, might file over $60,000 in claims, yet Affordable Care Act rules allow such patients to buy coverage for far less, forcing insurers to take a loss on every such patient. That creates “an incentive to avoid enrolling people who are in worse health” by making policies “unattractive to people with expensive health conditions,” as explained by the Kaiser Family Foundation. This triggers a race to the bottom, such that each year, whichever insurer offers the best coverage attracts the most patients and incurs the most losses. Such insurers then either leave the market, as many have, or cut their coverage. The result is lower-quality coverage for many expensive conditions. The researchers find these patients face higher cost-sharing, more prior-authorization requirements, more mandatory substitutions, and often no coverage for the drugs they need, so that consumers “cannot be adequately insured.”

But overall, as summarized by researchers:

Rather than sparking a revolution, the ACA [Affordable Care Act] in most dimensions represents an extension of business as usual. The individual insurance market has been transformed by requiring insurers to offer coverage to everyone on the same terms, and by giving consumers a choice of competing private insurance options. Otherwise, we have not seen substantial, permanent change in the way health care is financed and delivered in this country. Enrollment in exchange plans has been dwarfed by increased enrollment in Medicaid. Millions of lower-middle-class people have been priced out of the individual market. Coverage has become more affordable for millions of people, largely due to increased federal subsidies. Health care costs continue to rise, and efforts to promote greater efficiency in health care delivery have been disappointing.

One summary of how Obamacare has fallen short of its goals as of June, 2021, is provided by Megan McArdle at the Washington Post, as follows:

Obamacare’s supporters talked a lot about illnesses contributing to more than half of all bankruptcies, which implied there should have been a sharp decrease in 2014, when Obamacare’s major coverage provisions took effect. There wasn’t. Obamacare’s supporters frequently cited America’s abysmal infant mortality rate, which implied that once Obamacare was in full swing, infant mortality should decrease sharply. It didn’t. Obamacare’s supporters claimed that tens of thousands of people were dying every year because they didn’t have health insurance, which implied that by 2019, our overall mortality rate should be substantially lower than it had been in 2009, with a noticeable kink around 2014. Instead, mortality rates, which had been trending downward, leveled off around that time.

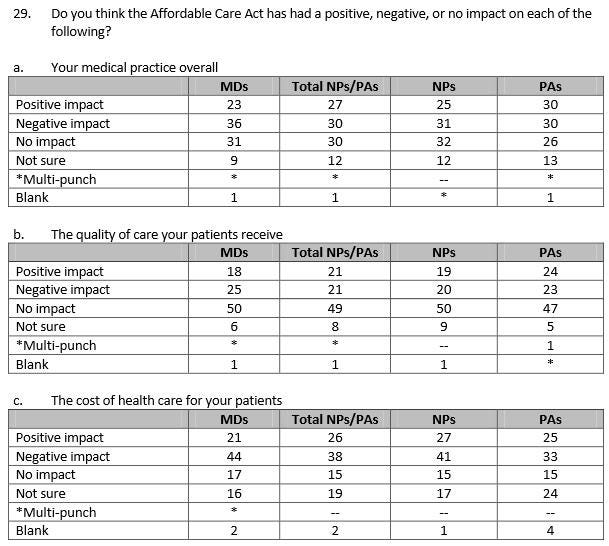

According to a 2015 survey of doctors by the Kaiser Family Foundation, more doctors believe the many regulations added by the Affordable Care Act has more negatively affected their overall practice, has more negatively impacted the quality of care their patients receive, and has more negatively impacted the cost of health care for their patients.

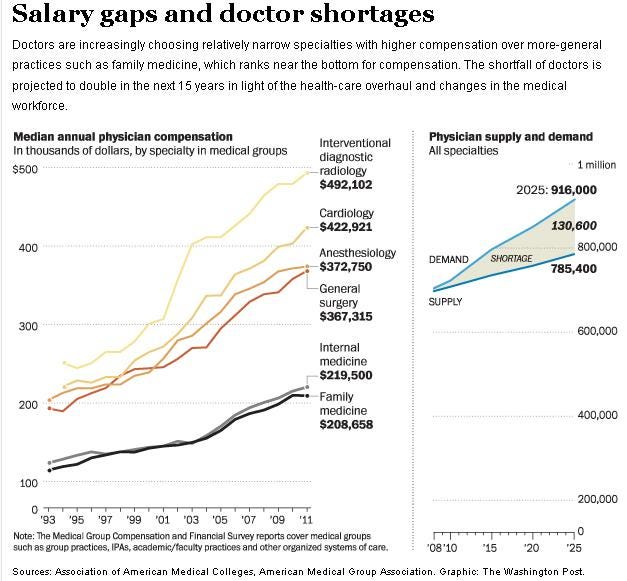

The greater bureaucracy regarding reimbursement created by the Affordable Care Act may worsen the shortage of doctors practicing general medicine, as medical professionals will choose instead relatively narrow specialties with higher compensation rates. This will direct more health care away from primary care physicians (who can recommend simple lifestyle changes) to specialists (who perform expensive medical procedures). A doctor shortage will also lead to more visits to emergency rooms.

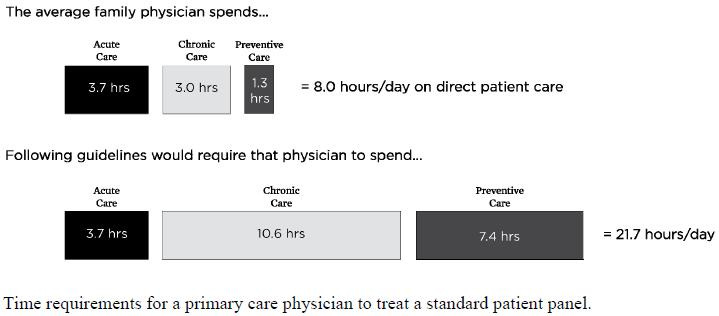

Existing family physicians are already overextended. Data compiled by the Institute for Medicine shows that if family physicians were to follow recommended care guidelines for treating a standard patient panel, they would be working over 21 hours per day.

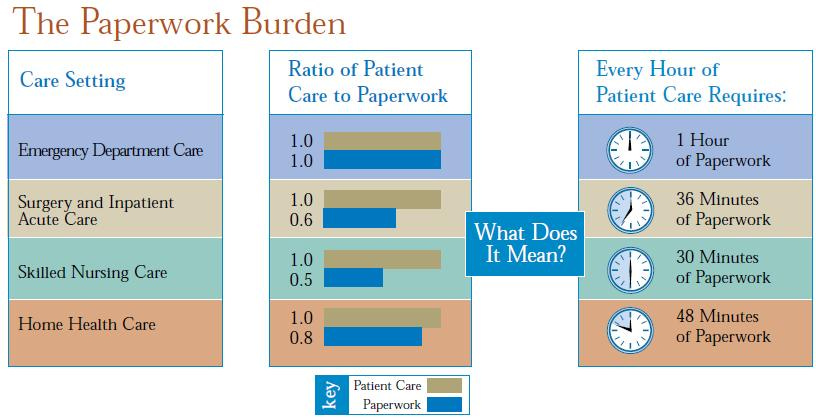

One hour of patient care requires about an hour of paperwork, and the Affordable Care Act imposes even more paperwork burdens.

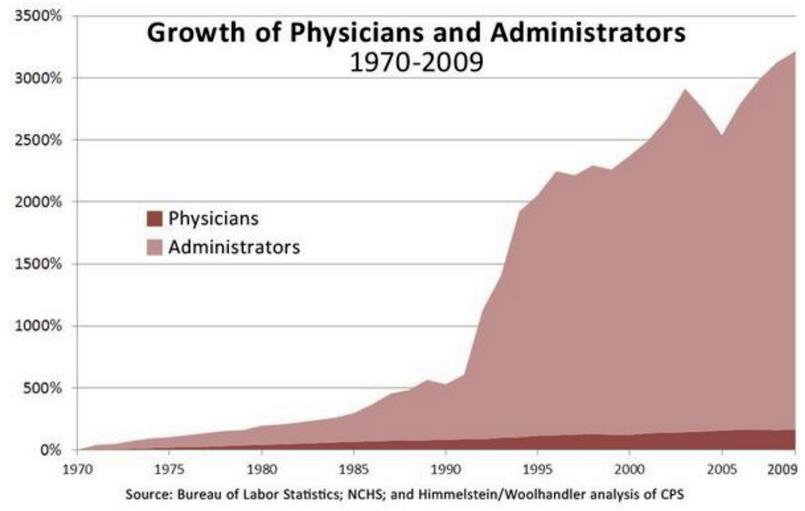

This chart shows how added regulations have led to hospitals’ having to hire many more administrators than physicians.

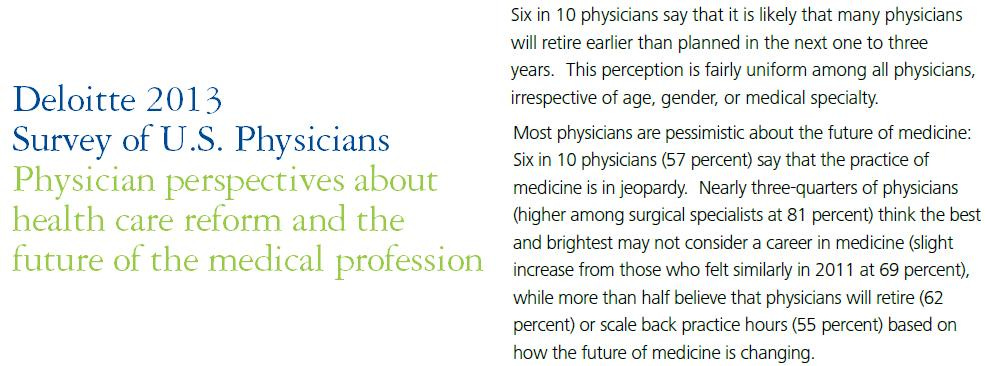

Most physicians surveyed a decade ago said it is likely more physicians will retire earlier than planned in the coming years, or scale back practice hours. Most physicians also thought the best and brightest may not consider a career in medicine, and that was prior to the creation of “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion” programs that impose yet more regulations that de-emphasize merit.

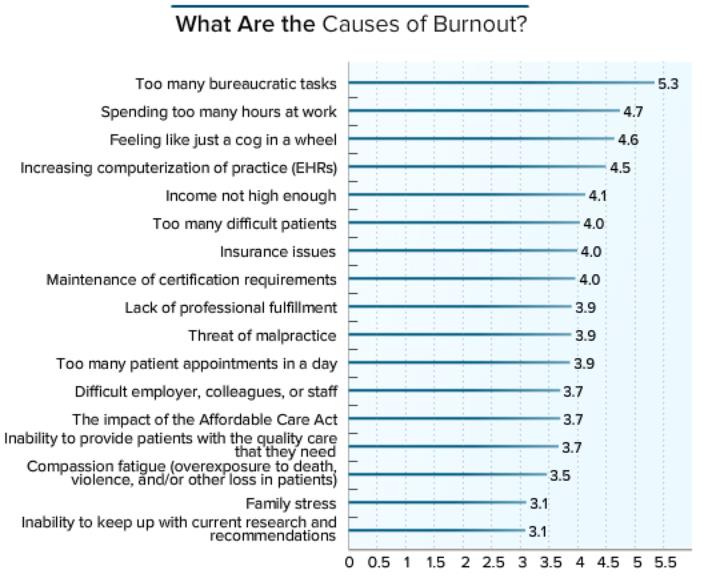

A 2017 survey of over 14,000 physicians asked them to identify their levels of professional happiness. Over 50 percent of respondents said they were “burned out,” a 25 percent increase from just four years ago. The number one driver of burnout was reported as “Too many bureaucratic tasks.”

As economist Noah Smith writes:

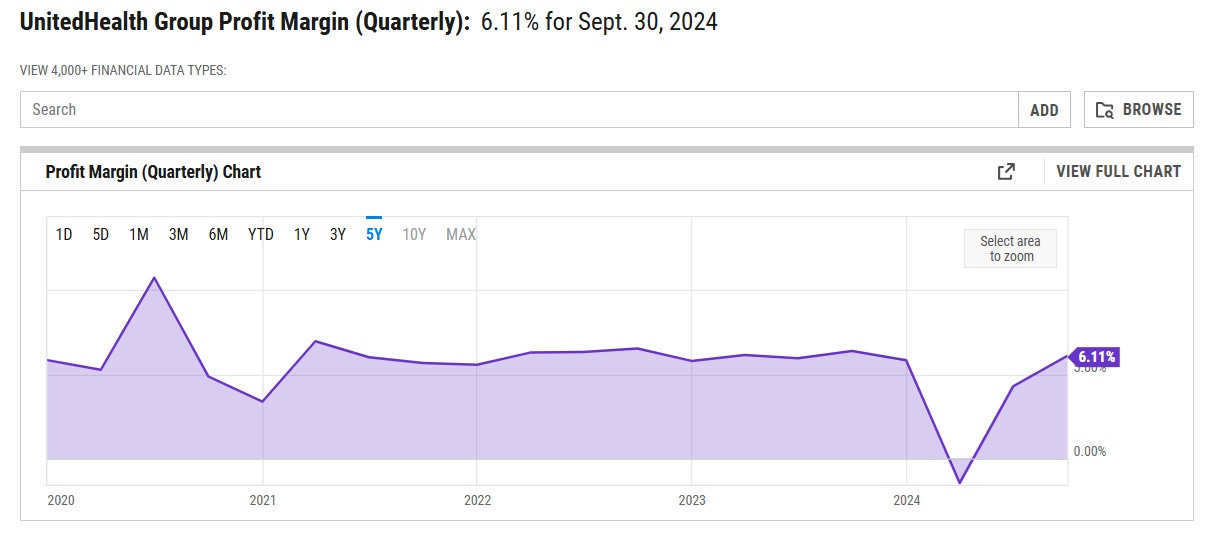

[W]hen we take a hard look at the question of why Americans pay so much more for their health care than people elsewhere in the developed world, insurance companies and their profits just aren’t that big of a piece of the story. First of all, insurance companies just don’t make that much profit. UnitedHealth Group … is the most valuable private health insurer in the country in terms of market capitalization, and the one with the largest market share. Its net profit margin is just 6.11%:

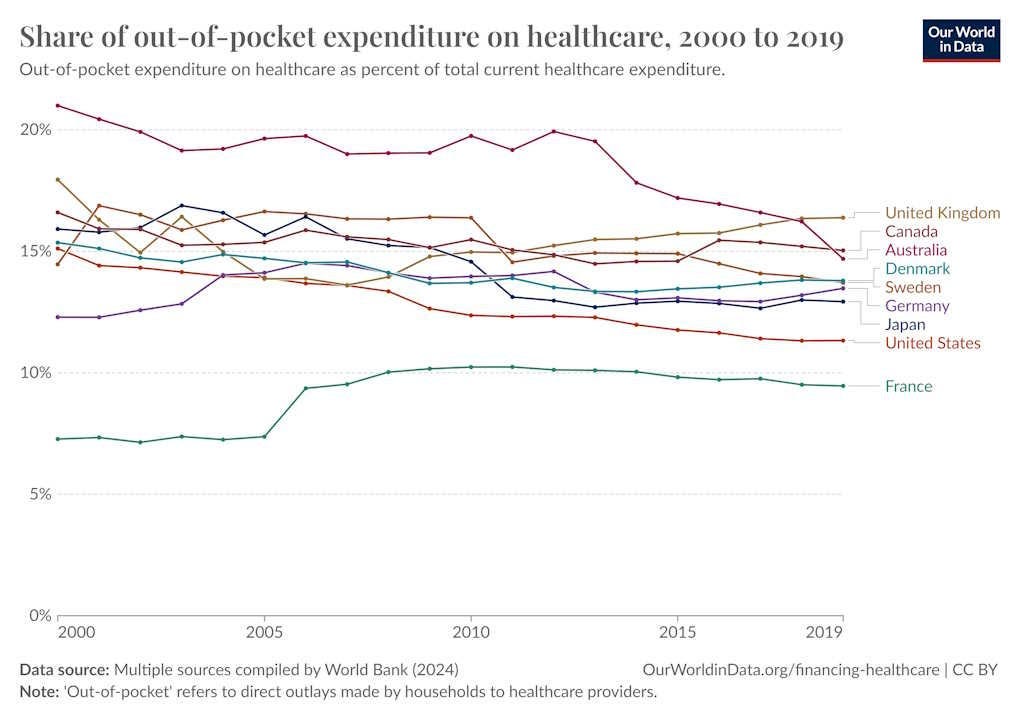

That’s only about half of the average profit margin of companies in the S&P 500. And other big insurers are even less profitable. Elevance Health, the second-biggest, has a margin of between 2% and 4%. Centene’s margin is usually around 1% to 2%. Cigna Group’s margin is usually around 2% to 3%. And so on. These companies are just making very little profit at all … What about those denials of coverage, copays, deductibles, and so on? In fact, Americans are paying a smaller percentage of their health costs out of pocket than people in most other rich countries!

… In other words, Americans’ much-hated private health insurers are paying a higher percent of the cost of Americans’ health care than the government insurance systems of Sweden and Denmark and the UK are paying. The only reason Americans’ bills are higher is that U.S. health care provision costs so much more in the first place … [T]he Kaiser Family Foundation does detailed comparisons between U.S. health care spending and spending in other developed countries. And it has concluded that most of this excess spending comes from providers — from hospitals, pharma companies, doctors, nurses, tech suppliers, and so on:

This means that eliminating all administrative waste and inefficiency in the entire U.S. health care system — not just at insurance companies, but administration of government insurance programs — could save Americans at most about $680 per person every year, and probably not anywhere close to that amount. A few hundred bucks a year is not nothing, but it’s only a small fraction of the $5683 more that we pay relative to other countries. So the fundamental reason your health care costs so much is not that the health insurance companies are lining their pockets. And it’s not that insurers are an inefficient mess. It’s that the actual provision of America’s health care itself just costs way too much in the first place. The actual people charging you an arm and a leg for your care… are the providers themselves.

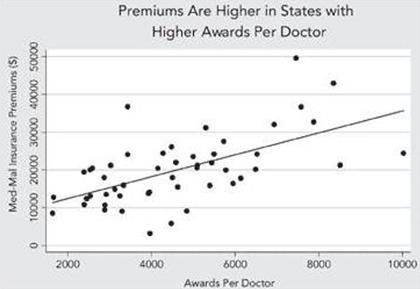

One reason providers themselves charge more money in America is because they face more lawsuits in America under our system. Doctors, for example, must pay tens of thousands of dollars annually for medical malpractice insurance to cover the risks of lawsuits. Data show that malpractice premiums are higher in states whose court awards are higher per doctor.

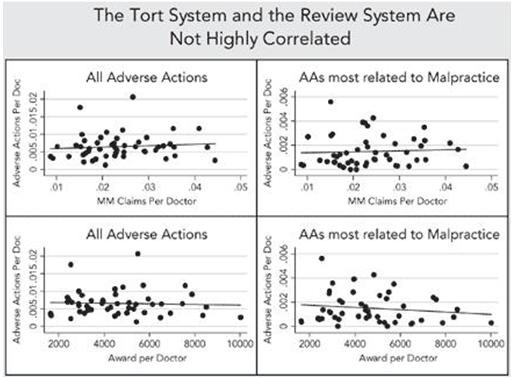

Data also show that adverse actions per doctor in the medical review board system do not correlate with the number of medical malpractice cases per doctor in the court system, nor do they correlate with the average award per doctor in the court system, indicating a disconnect between medical professional evaluations of error and determinations of legal liability in tort lawsuits.

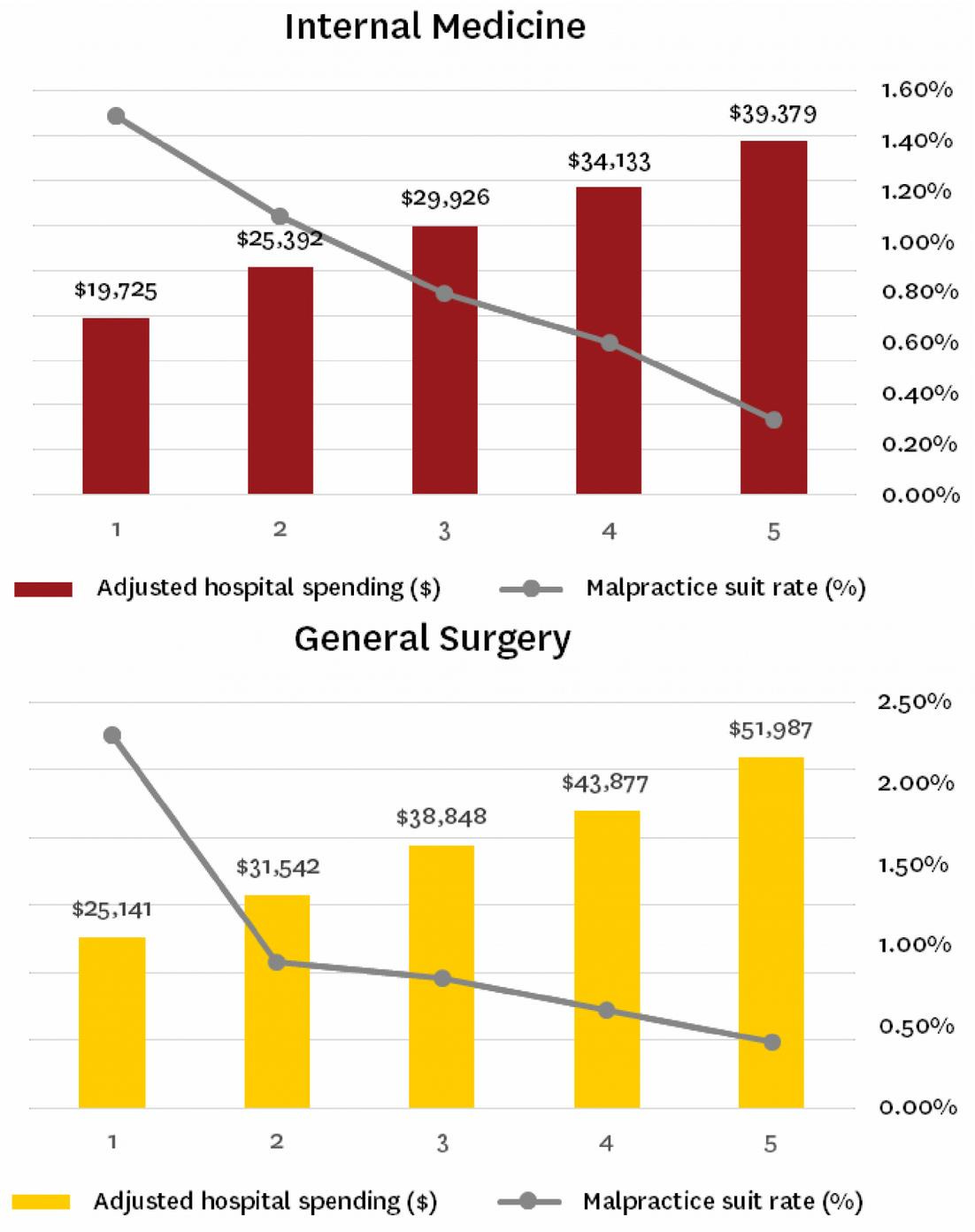

A 2015 study showed that the more money is spent on a patient by doctors and hospitals, the less likely that patient is to sue them if anything goes wrong. This poses problems for any cost-containment policy that does not also include litigation reforms that reasonably reduce liability exposure.

Also, researchers from Duke and M.I.T. compared people receiving care in the military health care system, in which military doctors have much greater protections from lawsuits, to the same people who left the military health care system, and found that the possibility of a lawsuit against the doctors increased the intensity of health care that patients received in the hospital by about 5 percent -- and that those patients who got such extra care were no better off.

In a future essay series, we’ll examine the many downsides of the American legal system more generally.

Finally, regarding deaths caused by medical errors at hospitals in America, over the years I’ve read some high estimates. But according to Vaclav Smil in his book How the World Really Works: The Science Behind How We Got Here and Where We're Going:

I should clarify the dangers associated with hospital stays. They are unavoidable because of many conditions (and in many countries also increasingly for elective cosmetic surgeries), and high patient throughputs make it more likely that medical errors will happen. In 1999, the first study of preventable medical errors found that anywhere between 44,000 and 98,000 of them are made in the US every year. That was an uncomfortably high total—and in 2016 a new study raised it to 251,454 cases in 2013 (and possibly to as many as 400,000 deaths), making it the third-highest cause of US mortality in that year, behind heart disease (611,000) and cancers (585,000) and ahead of chronic respiratory disease (149,000). These results, widely reported in the mass media, implied that every year 35–58 percent of all hospital deaths in the country were due to medical error. When put in this way, the implausibility of those claims become easily evident: careless errors surely take place, regrettable omissions do happen, but that they could add up to anywhere between just over a third and nearly three-fifths of all hospital deaths would brand modern medicine as an extraordinarily inept, if not outright criminal, endeavor. Fortunately, these high mortalities did not result from carelessness but from data-handling errors. The latest study of mortality associated with adverse effects of medical treatment (AEMT) sets the record straight: it found 123,063 such deaths between 1990 and 2016 (mostly due to surgical and perioperative errors), a decline of 21.4 percent to 1.15 AEMT deaths per 100,000 people.Men and women had similar rates, but states differed significantly, with California as low as 0.84 AEMT deaths per 100,000. In absolute terms this averages to about 4,750 deaths a year, less than 2 percent of the lowest estimate published in 2016. Translated into a comparative risk metric, this results in about 1.2 × 10-6 fatalities per hour of exposure, which means that any elderly male reader of this book (whose general mortality risk is between 3 × 10-6 and 5 × 10-6) will increase his risk of demise due to AEMT by no more than about 20–30 percent during the few days of an average stay in an American hospital—and that, I would argue, is a very encouraging risk finding!

In the next and final essay in this series, we’ll explore Charles Silver and David Hyman’s book Overcharged: Why Americans Pay Too Much for Health Care, which includes a good summary of the problems in medical care caused by third party payment systems.