The American Health Care System – Part 2

How paying less out-of-pocket leads to paying more, continued.

Continuing this essay series on the American health care system, this essay continues to explore how paying less medical care out-of-pocket leads to paying more for health care overall.

The 2017 price list below is from the website of Clinica Mi Pueblo, which is a chain of medical clinics in Southern California, serving primarily the Hispanic community. The clinics offer “general medicine services at the most affordable prices possible.” At that time, for example, the national average cost for an MRI was $2,611, but only $350 at the clinic. The median national cost of a colonoscopy was $1,626, but only $450 on the price list below. The U.S. average “fair” cost of an ultrasound was $263, but only about half that amount at the Clinica Mi Pueblo. This is possible because the clinic operates on a cash-only basis, with transparent prices that are listed on the clinic’s website. Further, the clinic accepted no insurance, and it would not submit insurance claims on patients’ behalf. If patients have insurance, they can easily take the paperwork the clinic provides and file an insurance claim on their own. Reducing the need to deal with the costly, time-consuming mountain of paperwork associated with insurance is one of the main reasons that cash-only medical clinics can keep their costs down and prices so low and affordable. Under the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare), on the other hand, deductibles for individuals enrolled in the lowest-priced Affordable Care Act health plans averaged more than $6,000 in 2017, and families enrolled in bronze plans had average deductibles of more than $12,000; regarding premiums under the Affordable Care Act, a 40-year-old unsubsidized bronze Affordable Care Act plan patient paid slightly more than $350 per month in 2017 for their “health coverage” with a deductible of more than $6,000. In contrast, spending $350 per month out-of-pocket at Clinica Mi Pueblo, instead of going toward an Affordable Care Act plan that provides almost no actual medical care, would actually purchase quite a lot of actual medical services. As explained by Mark Perry at the American Enterprise Institute: “For routine medical care (annual physicals, flu shots, routine office visits, X-Rays, ultrasounds, MRIs, blood tests, etc.) most Americans, especially younger, healthier patients, would be much better off with a cash-only medical clinic like Clinica Mi Pueblo than with Obamacare.”

In another study from the 1980s, the RAND Corporation conducted an extensive experiment in which people were given different levels of co-payment insurance. Those who paid more out-of-pocket visited doctors less often, were admitted to hospitals less frequently, and generally spent less on health care, but with no adverse effects on health.

As Robin Hanson describes the Rand study in The Elephant in the Brain:

Between 1974 and 1982, the RAND Corporation, a nonprofit policy think tank, spent $50 million to study the causal effect of medicine on health. It was, and remains, “one of the largest and most comprehensive social science experiments ever performed in the United States.” Here’s how the RAND experiment worked. First, 5,800 non-elderly adults were drawn from six U.S. cities. Within each city, all participants were given access to the same set of doctors and hospitals, but they were randomly assigned different levels of medical subsidies. Some patients received a full subsidy for all medical visits and treatments; they could consume as much medicine as they wanted without paying a dime. Other patients received discounts ranging from 75 percent to 5 percent off their total bill. Note that a 5 percent discount is effectively unsubsidized, but the researchers needed to give patients some incentive to enroll in the study. Patients remained in the program between three and five years. As expected, patients whose medicine was fully subsidized (i.e., free) consumed a lot more of it than other patients. As measured by total spending, patients with full subsidies consumed 45 percent more than patients in the unsubsidized group. This 45 percent difference constituted the marginal medicine examined in this study, that is, the medicine that some people got that others did not. Despite the large differences in medical consumption, however, the RAND experiment found almost no detectable health differences across these groups. To measure health, comprehensive physical exams were given to all participants both before and after the study. These exams included 22 physiological measurements like blood pressure, lung capacity, walking speed, and cholesterol levels. The exams also used extensive questionnaires to gauge five measures of overall well-being: physical functioning, role functioning (i.e., at work), mental health, social health, and general health perception … For the five measures of overall well-being, all groups fared the same. Of the 22 physiological measurements, only one—diastolic blood pressure—showed a statistically significant improvement in the fully subsidized group (relative to the other groups). But this is an outcome we should expect purely by chance. Out of 20 noisy measurements, on average, 1 of them will randomly appear to differ from zero (at a 95 percent confidence interval), even if all the underlying values are actually zero. Needless to say, the RAND experiment researchers were surprised by their results. To look more closely, they wondered if their fully subsidized patients were choosing treatments that were less effective than the treatments chosen by other patients. For example, maybe the fully subsidized patients decided to get unnecessary surgeries, or to visit the doctor when they had milder symptoms. Unfortunately, this wasn’t the case. Doctors who were asked to look at patient records couldn’t tell the difference between the fully subsidized and unsubsidized patients … Remember, we’re not asking whether some medicine is better than no medicine, but whether spending $7,000 in a year is better for our health than spending $5,000. It’s perfectly consistent to believe that modern medicine performs miracles and that we frequently overtreat ourselves.

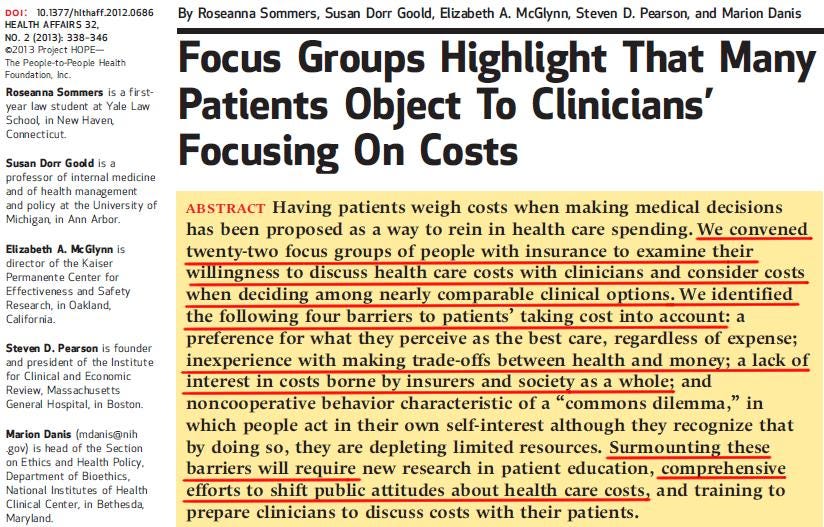

When people obtain health insurance coverage for needed expenses but are also required to cost shop to save money, health care spending goes down significantly without an increase in adverse results. But because under the current system, Americans have so little experience matching costs with health care options, they are much less likely now to demonstrate interest in saving health care costs, even when given nearly identical clinical options that have widely different costs.

As Robin Hanson writes in The Elephant in the Brain:

In fact, patients show surprisingly little interest in private information on medical quality. For example, [researchers found that] patients who would soon undergo a dangerous surgery (with a few percent chance of death) were offered private information on the (risk-adjusted) rates at which patients died from that surgery with individual surgeons and hospitals in their area. These rates were large and varied by a factor of three. However, only 8 percent of these patients were willing to spend even $50 to learn these death rates. Similarly, when the government published risk-adjusted hospital death rates between 1986 and 1992, hospitals with twice the risk-adjusted death rates saw their admissions fall by only 0.8 percent. In contrast, a single high-profile news story about an untoward death at a hospital resulted in a 9 percent drop in patient admissions at that hospital.

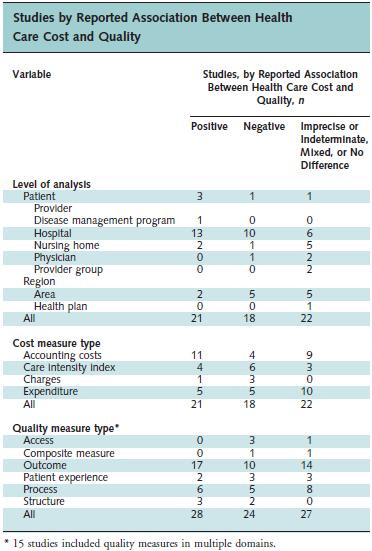

When consumers stop comparing costs, there is less connection between cost and quality of care.

Most studies have found that, under the current system, the association between health care cost and quality is small to moderate, regardless of whether the direction is positive or negative.

A report of the costs of the most common patient procedures at hospitals reveals a huge range of prices charged for the same procedure.

Because we lack a price-competitive health care system, researchers have not found significant correlations, if they find them at all, between health care spending and improved health care outcomes.

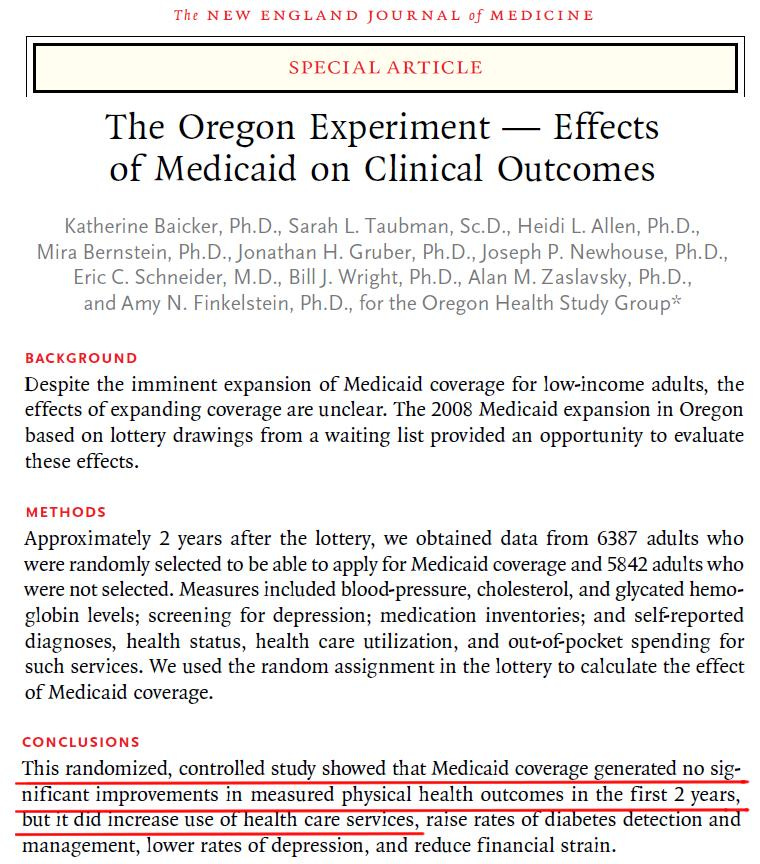

A unique randomized and controlled study showed that coverage under Medicaid did not result in increased physical health, but did increase the use of health care services.

Another study examining the same data concluded that -- contrary to those who argued that expanding Medicaid would reduce costly and inefficient use of hospital emergency rooms by increasing access to primary healthcare -- Medicaid coverage actually increased emergency room visits by 40 percent.

Other researchers similarly found the following:

This paper provides new evidence on the causal relationship between income and health by studying a randomized experiment in which 1,000 low-income adults in the United States received $1,000 per month for three years, with 2,000 control participants receiving $50 over that same period … [W]e find no effect of the transfer across several measures of physical health as captured by multiple well-validated survey measures and biomarkers derived from blood draws. We can rule out even very small improvements in physical health and the effect that would be implied by the cross-sectional correlation between income and health lies well outside our confidence intervals. We also find that the transfer did not improve mental health after the first year and by year 2 we can again reject very small improvements. We also find precise null effects on self-reported access to health care, physical activity, sleep, and several other measures related to preventive care and health behaviors.

The Kaiser Family Foundation reviewed 108 studies of the Affordable Care Act’s impact and found that, though beneficiaries used more health care, the “effects on health outcomes” are unclear.

In a 2019 paper, researchers reported they found that “a substantial share of the federally-funded Medicaid expansion [under the Affordable Care Act] substituted for existing locally-funded safety net programs … On the benefits side, we do not detect significant improvements in patient health, although the expansion led to substantially greater hospital and emergency room use ...”

In the next essay in this series, we’ll explore more evidence of dysfunctions in the American health care system.