The American Health Care System -- Part 4

A summary of the problems caused by third party payments in medical care.

In this final essay in this series, we’ll explore Charles Silver and David Hyman’s book Overcharged: Why Americans Pay Too Much for Health Care, which includes a good summary of the problems in medical care caused by third party payment systems.

Silver and Hyman introduce the problem as follows:

To make health care better and cheaper for all Americans, we must change the way we pay for medical services. That is what this book explains. Our system costs too much and delivers too little because we pay for health care the wrong way. Instead of routing dollars through insurers, public payers like Medicare and Medicaid, and politicians, consumers must control the money. They must choose the health insurance plans and medical services they use and pay for them directly, the same way they choose and pay for goods and services of other types. If and when consumers take charge, the American health care system will quickly improve. Until then, it will not … Third-party payment for most health care expenses compounds the problems created by political control of health care spending. Consider what happened to a mutual friend of the authors, whose stitches gave out after he sustained a minor wound. He went to a hospital-owned urgent care center in a strip mall and spent 30 minutes having his injury treated. He subsequently received a bill for $3,000, which he thought was absurd on its face, and likely fraudulent. However, the center granted a $1,170 discount based on its relationship with his insurance company, which then unquestioningly paid the “allowed” amount—$1,770—leaving him with a nominal bill of $60. When he saw that he personally owed so little, he shrugged his shoulders and paid the balance. Does anyone believe his reaction would have been the same if he had been responsible for the full $1,830 the center received—let alone the $3,000 list price? Does anyone believe that health care providers would send out such inflated bills if third-party payment were not the rule? … Proponents hailed Obamacare as a revolutionary transformation, but it really just doubled down on the failed strategy of third-party payment. The payment system was already funneling unprecedented amounts of money into the health care sector—and Obamacare threw gasoline on the fire by offering subsidized insurance and vastly expanding Medicaid. If cost control was ever the object, Obamacare was designed to fail.

Silver and Hyman relate a short history of American healthcare policy:

Before the role of third-party payers expanded dramatically during and after World War II, health care was cheap and people paid for it directly. Spending really took off in the 1960s, when Medicare and Medicaid came online. As Professors Ted Marmor and Jon Oberlander write: “In the first year of Medicare’s operation, the average daily service charge in American hospitals increased by an unprecedented 21.9%. The average compound rate of growth in this figure over the next five years was 13% … In the eleven months between the time Medicare was enacted and the time it took effect, the rate of increase in physician fees more than doubled, from 3.8% in 1965 to 7.8% in 1966. The average compound rate of growth in physician fees remained a high 6.8% over the next five years. In the first five full years of Medicare’s operation, total Medicare reimbursements rose 72%, from $4.6 billion in 1967 to $7.9 billion in 1971. Over the same period, the number of Medicare enrollees rose only 6%, from 19.5 million in 1967 to 20.7 million in 1971.” … It is worth reflecting on how enormous the spending increase has been. In 2016, Americans spent about $3.4 trillion on health care. In 1960, we spent only $27 billion. That’s an average increase of 9 percent per year. Had health care spending grown at the same rate as the general economy, it would have been about $220 billion in 2016, just under 7 percent of the figure it actually was … As health care spending was exploding, however, the percentage of dollars that came directly from consumers (rather than being routed through the hands of third- party payers) drastically declined. In the early 1960s, patients paid about $1.80 out- of- pocket for every $1 spent by third-party payers. After Medicare and Medicaid were created, that ratio declined so steeply that, by the end of the decade, it was approximately $1 to $1. Today, consumers directly contribute less than 20 cents for every dollar shelled out by a third- party payer. The less direct responsibility consumers bear for the costs of medical services, the more total spending increases … To bend the cost curve downward, we need to rely less on third-party payers and more on ourselves.

Silver and Hyman then explain how reserving insurance for only “big-ticket” items is how we’ve managed to keep costs down among many other things essential for life:

[E]xcessive reliance on third-party payers has convinced Americans that they cannot and should not pay for medical services themselves. Tens of millions of people who would never think of using insurance to pay their mortgages or their rent reflexively use their health care coverage to pay for doctors’ office visits and other medical services that cost far less. To dig ourselves out of this hole, we have to learn to treat health care like everything else. We should pay for most medical treatments directly, the same way we pay for housing, transportation, electricity, water, food, and clothes. Insurance should be reserved for calamities.

Silver and Hyman explain that, without consumer checks on cost, waste, fraud, and abuse is easier to commit:

Medicare and Medicaid are plagued by fraud, waste, and abuse. The fastest way to enrich health care providers is to pay claims without checking to see that services were even provided. That’s why these programs pay first and ask questions later—if ever. This approach, commonly known as “pay and chase,” makes it easy for career criminals and Main Street providers to steal billions of taxpayers’ dollars. And, once the money is gone, there is no hope of getting it back. In 2014, the Department of Justice had one of its best years ever, making fraudsters cough up $3.3 billion.16 But that very same year, wrongdoers drained almost $100 billion from the Treasury by filing false Medicare and Medicaid claims. The feds are not even fighting the criminals to a draw; they are getting creamed … +If the payment system were designed sensibly, self-pay would be the rule. Health care coverage would be reserved for disasters, just like other forms of insurance. Auto insurance covers major crashes, not small dings and certainly not oil changes. Life insurance kicks in when people die, not when they miss a day at work because of a sore throat. Homeowners’ insurance covers damage inflicted by serious fires, water leaks, and windstorms—and it has sizable deductibles, to get homeowners to bear all of the costs of minor problems and to share the costs of major disasters … Health care coverage should work similarly. Insurers should pay for highly complex and expensive procedures that relatively few people need in any given year. Patients should pay for routine stuff—like check-ups, diabetes monitoring, and allergy medications … [T]he health care cost crisis is driven by third-party payment and always has been. Here’s how it works, in seven easy steps: Health insurance and public programs like Medicare and Medicaid stimulate demand for more and more expensive health care. Increased demand for more and more expensive health care drives up prices. Rising prices inspire fear in consumers, who worry that they won’t be able to afford health care when they need it. Fearful consumers demand more health insurance, insurance that covers more things, and more lavish public programs. Tax preferences for employment-based health insurance add fuel to the fire, by encouraging people to buy more insurance and more comprehensive insurance than they otherwise would. More and more comprehensive health insurance and more lavish public programs stimulate demand for more and more expensive health care. Return to Step 2. This vicious cycle continued until the first decade of the 21st century, when private health care coverage became so expensive that millions of people could no longer afford it. Then the Great Recession hit, cost millions of people their jobs and their insurance, and demand was depressed even further. For a while, it seemed that health care spending would moderate on its own. Obamacare got the vicious cycle going again. By requiring people to carry comprehensive insurance coverage, subsidizing premiums, and expanding Medicaid enormously, it reignited the fire.

Silver and Hyman remark on the basic incentives involved in third party payments:

Payers want health care to be expensive. The reason is simple. If medical services were cheap, we wouldn’t need Medicare, Medicaid, or private insurers to bear the cost for us. In 2016, the median family with two adults and two children spent almost $17,000 on housing and about $8,300 on transportation, without any help from insurance companies. If medical services predictably cost only a similar amount each year, people could pay for them directly too. This would make consumers and patients happy, but third-party payers would be sad. The need to route more than $1 trillion through the Medicare and Medicaid programs would vanish. The need for private insurers would diminish too … The more expensive health care becomes, the happier payers are. The more medical services cost, the more people will want the protection from risk that Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers provide … Because expensive health care makes third-party payers’ services essential, their business model depends on fear. They need patients and consumers to be terrified that health care expenses will ruin them. Consequently, they won’t work to change the system in ways that would put consumers at ease … Until the second half of the 20th century, doctors and hospitals opposed the government’s efforts to stick its nose into their business. Although few people alive today know the history, organized medicine bitterly opposed the creation of Medicare. Dr. Donovan Ward, the head of the American Medical Association (AMA), declared that “a deterioration in the quality of care is inescapable.” Similarly, the president of the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons stated that it would be “complicity in evil” for doctors to participate in Medicare. The AMA even hired Ronald Reagan to read a speech on the threat that socialized medicine posed to the American way of life and sent copies of the recording to every doctor’s office in the United States. Today, doctors are Medicare and Medicaid’s biggest fans. Opposition morphed into support when they realized that, with the government footing the bills, they could raise their rates—which they immediately did. As Harvard economist Martin Feldstein observed way back in 1970, “after [the] introduction of Medicare and Medicaid, physicians’ fees rose at 6.8 per cent per year in 1967 and 1968 in comparison to a 3.2 per cent annual rise in the [consumer price index].” Government programs put money in doctors’ pockets, so organized medicine did a 180-degree turn … The effect of insurance on hospitals’ charges was even more pronounced. Again, [Martin] Feldstein did the pioneering research. He opened The Rising Cost of Hospital Care by observing that “A day of hospital care in 1970 cost … five times as much as in 1950”—a staggering increase, especially because “the general price level of consumer goods and services [rose] less than 60%” over the same period. From 1966 to 1970, the last five years Feldstein studied, hospital prices rose annually by almost 15 percent. Why? The main driver was the growing availability and generosity of public and private insurance. Over the two decades Feldstein studied, the fraction of hospital care paid for by some form of insurance rose markedly. In 1950, the split between insurance and patient responsibility was roughly 50–50. If a hospital day cost $600, the insurer paid $300 and the patient paid $300. By 1968, insurers were picking up 84 percent of the cost.12 This meant that, at $600 per day, the insurer paid $504 and the patient only $96. The shift of financial responsibility to insurers was so dramatic that patients actually paid less even as hospitals raised their rates. Suppose that, from 1950 to 1968, the cost of a hospital day trebled, from $600 to $1,800. In 1950, the patient’s share would have been $300. In 1968, it would have been only $288. As wages rose and people became wealthier, hospital care seemed like a better bargain than ever, because more and more of its cost was being borne by insurers. The portion of hospital spending borne by public and private third-party payers kept increasing throughout the 20th century, and total health care spending rose right along with it. In recent research, Amy Finkelstein, a professor of economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, estimated that the spread of insurance was responsible for about half of the six-fold increase in real health care spending per capita that occurred from 1950 to 1990. In other words, insurance caused health care spending to triple. From 1965 to 1970 alone, Medicare drove up real outlays on hospital services by 37 percent. Similar increases were found across all age groups. When insurance inflates demand, prices rise across the board and everyone suffers.

Silver and Hyman use another analogy to car insurance to show why near-universal medical care insurance coverage creates dysfunctions we don’t see in car insurance policy:

It’s easy to see why insurance stimulates demand. At the point of sale, people don’t spend their own money. This makes medical services seem cheap or even free, so people naturally want more of them. And, just as naturally, they care very little about the total cost of the services they use. The average price of a total knee replacement is about $31,000. That’s about what you’d pay for a new Audi Q3, a small luxury crossover SUV. But the average patient who undergoes a knee replacement pays less than 10 percent of the total, say, $3,000. The rest is covered by insurance. If the same arrangement existed in the auto market—call it “new car insurance”—you could buy a $31,000 Audi Q3 for $3,000. So you’d happily take one—or maybe several—even if you would never pay $31,000 out-of-pocket for this particular car. Insurance generates demand for medical treatments in the same way. You pay a monthly premium over which you have little control, often because the dollars are withheld from your salary. And, once that money is spent on insurance, it isn’t coming back, whether or not you actually use any health care … The evil genius of health insurance is that, at the point of delivery, it encourages patients to overconsume by making medical services seem cheap … What’s true for you is also true for the millions of other people who carry insurance. You get to buy an Audi Q3 for $3,000 and so do they. Over time, the country will be flooded with new Audis and all of these new Audi owners will impoverish each other. Premiums will have to rise, because the money to pay for all the new Audis has to come from somewhere. Finally, as insurance-driven demand for Audis increases, Audi will increase its prices and aggregate spending will go through the roof … Clever studies have examined the impact of insurance on health care consumption. Several papers focus on Oregon’s decision to expand Medicaid in 2008. Oregon allowed anyone who met the eligibility criteria to apply, but it received far more applications than it could accept. So it randomly chose a subset of applicants to receive Medicaid coverage. This created a natural experiment, that is, an especially good opportunity to study the impact of insurance on health care utilization. Because the applicants who received Medicaid (the “winners”) were chosen at random from the same pool as those who did not (the “losers”), any differences in health care utilization between these two groups could be chalked up to insurance. The first article from the Oregon experiment in the medical literature appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2013.17 The researchers determined that “Medicaid coverage increased annual medical spending . . . by $1,172” per household. In other words, the winners used about 35 percent more medical services than the losers. Having Medicaid coverage made only a modest difference in the winners’ health, however, although it did reduce financial strain … A subsequent article on the Oregon experiment reevaluated the earlier findings using an additional year of data. The results were the same. “Newly insured people will most likely use more health care across settings—including the [emergency room] and the hospital.” … Another clever study focused on senior citizens and evaluated the impact of qualifying for Medicare on health care utilization.20 It compared people ages 62–64 to people who were 65. Because the two groups were so close in age, the health status of their members was similar. One might have expected the slightly older group to use a bit more medical care per person, but not much. In fact, hospitalizations, visits to doctors’ offices, and the use of prescription meds all spiked at age 65. Why? Because that’s when people become eligible for Medicare. The older people used lots of Medicare-financed health care that the people in the 62-to-64-year-old bracket, many of whom lacked insurance, wouldn’t (or couldn’t) pay for themselves. It is hard to come up with better evidence that the demand for medical treatments is, in fact, quite elastic … Feldstein, the Harvard economist, described the cycle more than 40 years ago: The price and type of health services that are available to any individual reflect the extent of health insurance among other members of the community. . . . [P]hysicians raise their fees (and may improve their services) when insurance becomes more extensive. Nonprofit hospitals also respond to the growth of insurance by increasing the sophistication and price of their product. . . . Thus, even the un-insured individual will find that his expenditure on health services is affected by the insurance of others. Moreover, the higher price of physician and hospital services encourages more extensive use of insurance. For the community as a whole, therefore, the spread of insurance causes higher prices and more sophisticated services which in turn cause a further increase in insurance. People spend more on health because they are insured and buy more insurance because of the high cost of health care … The connection between third-party payment and health care spending will be obvious to anyone who bothers to look. In Figure 15-1, the line shows the ratio between the amounts that consumers paid directly for health care and the amounts that were spent by Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers (left-side axis). The line starts out at about 1.80, meaning that in 1960 consumers paid $1.80 out of pocket for every dollar spent on medical services by a third-party payer. Then it declines steadily, so that, by 2010, for every dollar a payer shelled out, a consumer spent less than 20 cents. The decline in direct, personal financial responsibility was especially pronounced in the mid-1960s, when Medicare and Medicaid were introduced. The vertical bars show annual health care spending per capita (right-side axis). It rises from a few hundred dollars in 1960 to over $8,000 per person in 2010. As direct payment falls, per capita spending rises. The more heavily we rely on third-party payers, the more we spend.

Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “National Health Expenditures by Type of Service and Source of Funds: Calendar Years 1960 to 2015,” available at https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.html.

Silver and Hyman return to the example of LASIK surgery:

The now-classic example of declining retail prices is LASIK, an outpatient surgical procedure that ophthalmologists perform to improve patients’ vision. LASIK isn’t covered by insurance, so patients pay for it directly and price competition is fierce. Google “LASIK” and you’ll find lots of advertisements from doctors who offer the service. Many ads include information about prices—the very information hospitals claim to be unable to provide about other surgeries. You can also find LASIK Groupons galore, and there are price-comparison websites that help explain doctors’ pricing strategies. If you decide to have LASIK, you’ll know the cost up front and you won’t have to worry about hidden charges or being gouged. You’ll also save money on LASIK if you buy it today because, from 1996 to 2005, the real price of the service fell by nearly 30 percent. Competition made LASIK cheaper, thereby making it more easily available to millions of Americans who would otherwise have done without it or, at least, put it off until they could afford it. In real dollars, cosmetic surgery became less expensive too. From 1992 to 2013, “the price of consumer goods, as measured by the inflation rate, increased by about 64 percent. . . . Yet, during this same period, the price of cosmetic medicine rose only about 30 percent—less than half of the consumer price increase.” At the same time, demand boomed. More than 10 times as many cosmetic procedures are delivered today as were performed two decades ago. Why did LASIK and cosmetic procedures become more affordable? Consumer demand, first-party payment, and competition. As Devon Herrick, a leading commentator on retail health care, explained: Doctors who perform cosmetic services quote package prices, and generally adjust their fees to stay competitive. The industry is constantly developing new products and services that expand the market and compete with older services. As more cash-paying patients demand procedures, doctors rush to provide them. There are few barriers to entry in cosmetic surgery. Any licensed physician can enter the field. When we pay for health care the same way we pay for other services—by spending our own money instead of an insurer’s—good things happen: prices fall and quality improves as providers compete for business … By comparison, over the same period that LASIK and cosmetic surgery became cheaper, the prices of medical services covered by insurers rose at two to three times the rate of inflation.16 Can you think of a single hospital-provided service whose price, like LASIK, is 30 percent lower today than it was a decade ago? We can’t. Prices rise even for services that use old technologies. Computers are faster and cheaper today than ever before, but the same cannot be said for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), CT scans, electrocardiograms, or ultrasound tests when performed in hospitals.

Silver and Hyman make clear that the dysfunctions in the healthcare system aren’t cause by bad people, but rather bad incentive structures:

The executives who run companies that deliver medical treatments in the retail sector are not angels, and those who run hospitals are not devils. All are managing their companies in profit-maximizing ways. Retail-medicine executives would probably charge outrageous prices too if they could. But they can’t, because they have to compete with other retailers for cost-conscious patients. And that’s the point.

Silver and Hyman then describe the sort of insurance that is more suited to healthcare:

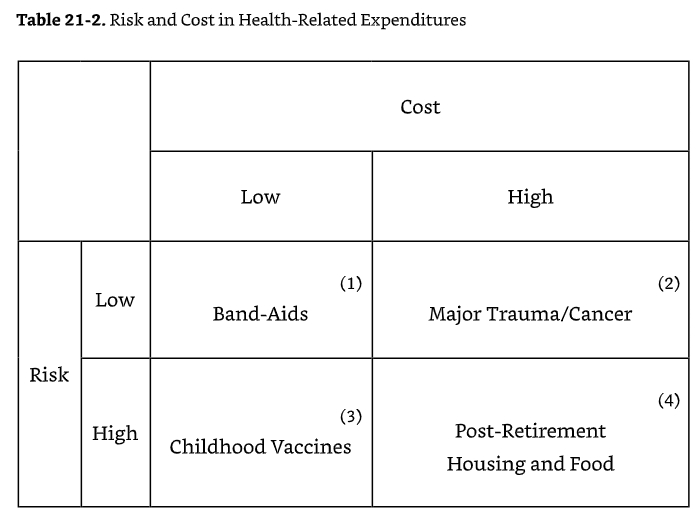

What we want are policies that would encourage people to use insurance to handle the problems that insurance is well suited for. Right now, health insurance mostly covers the wrong things. It also pays too much (and does so in almost the worst way imaginable) for most of what it covers … [I]n the non-health care economy, insurance is sold mainly to cover risks where there is a low (and often tiny) likelihood of a bad outcome, but with catastrophic consequences when the risk materializes. Conversely, when loss-causing events are highly likely … [I]nsurers can’t offer inexpensive protection, so there isn’t much (if any) demand for insurance. And, if the costs and risks are low enough … [N]o one wants to buy or sell insurance against those situations either. How does this framework apply to health care?

[I]nsurers don’t add value for the kinds of problems that land in Cells 1, 3, and 4. For Cell 1, the cost of Band-Aids is sufficiently trivial that no one would buy insurance against that eventuality. Similarly, for Cell 3, if you have children, the likelihood of needing to pay for vaccines is 100 percent—at least, if you care about keeping your kid from dying of measles or whooping cough. And for Cell 4, the likelihood of needing housing and food in one’s old age is quite high and the cost is large as well. These aren’t the kinds of situations that normally give rise to a robust demand for insurance. And, except for the minority of seniors who require some form of long-term care, there is no market for post-retirement housing insurance. Finally, as Cell 2 indicates, health insurance is a good way of protecting people against remote risks, such as the risk of being severely injured in a car crash and needing expensive medical treatments … [I]nsurance works well for the type of problems that fall into Cell 2 because insurers can protect people from catastrophic outcomes while charging relatively modest premiums. When the risk is low but the ultimate cost is extremely high, voluntary markets emerge where consumers can transfer that financial risk to an insurer willing to accept it … To sum up, health care coverage works well for low-probability, high-cost events (Cell 2), but like other types of insurance it has little to offer for other probability/cost combinations. Stated differently, insurance is a good way of paying for health care when each member of a sizable population faces a small risk of suffering a large loss. But insurance is a bad way of dealing with losses that do not fit this description, including inexpensive medical treatments and treatments for chronic illnesses and other maladies that people are certain to need. The way to deal with these costs is simply to pay for them. The money can come directly out of consumers’ pockets or it can come from somewhere else, as it does when people who are too poor to pay for the needed services receive financial support—welfare or charity—from others. For everything other than low-probability, high-cost events, insurance doesn’t work … The type of insurance that works is often called catastrophic coverage. It protects people from large losses by applying after they meet substantial out-of-pocket minimums or deductibles. Catastrophic coverage is cheap because insurers expect people to use it infrequently. The type of insurance that doesn’t work is called comprehensive coverage. It combines catastrophic coverage with a prepayment plan for medical expenses that fall into Cells 1, 3, and 4. This is the type of insurance that most people have and that Obamacare requires them to purchase.

Silver and Hyman then explain how current federal health care policy robs a younger Peter to pay an older Paul:

People are rarely bothered by the fact that insurance markets tie premiums to risks. Few seem to think that regulators should intervene and force carriers to charge everyone the same thing. Why should safe drivers pay more so that careless drivers can pay less? Why overcharge people who live in areas devoid of trees pay to subsidize people with houses in fire zones? In the wake of the hurricanes that recently devastated parts of Texas and Florida, many people who live inland are wondering why their tax dollars are used to subsidize insurance for people who choose to live near the coasts. Shouldn’t the latters’ taxes be increased to reflect the risk they incur by purchasing homes that are more likely to be flooded? As a general matter, people seem content to let prices vary across persons according to actual risks, which happens naturally when markets set insurance prices. But many people think about health insurance differently. They think it is unfair and morally indefensible for high-risk people to pay more than low-risk people for the same coverage. Unfortunately, these proponents of cross-subsidization rarely acknowledge that their objective is to coerce low-risk people into giving wealth to others. Instead, they deliberately obscure the reality that the policies they support are a bad deal for most people. Chris Conover discussed the impact community rating would have on young people, whom Obamacare overcharges so that older people can pay less.3 Rates for people ages 18–24 had to increase by 45 percent above the actuarially fair price so that the rate for those ages 60–64 could be reduced by 13 percent. “Is this fair?” Conover wondered. Ask the typical 20–24 year-old—whose median weekly earnings are $461—whether it’s fair to be asked to pay 50 percent higher premiums so that workers age 55–64—whose median weekly earnings are $887—can pay lower premiums. Think about that. The median earnings for older workers are $420 a week more than those of younger workers, or roughly $20,000 more a year. How is mandating a price break on health insurance for this far higher income group at the expense of the lower income group possibly fair? … Jonathan Gruber, a health economist who helped design Obamacare, admitted that cross-subsidization is at the heart of the program. He also acknowledged that transparency about forced wealth transfers would have doomed the bill: “If you had a law which … made it explicit that healthy people pay in [and] sick people get money it would not have passed … Lack of transparency is a huge political advantage, and basically, call it the stupidity of the American voter or whatever, but basically that was really, really critical for getting the thing to pass.” … According to Gruber, if the American people had understood that Obamacare was really an off-the-books welfare program, Congress would not have passed it because even more Democrats would have voted against it.

Silver and Hyman make a key point:

It is morally desirable to help poor people, people with chronic medical conditions, and others with the cost of health care. But it is a terrible idea to use the insurance system to accomplish this goal. Welfare programs are designed to redistribute wealth to those who have lost life’s lottery; insurance is a financial instrument designed to keep people from losing that lottery. The two differ greatly and should not be confused or combined.

Silver and Hyman then explain how the federal healthcare system is on an unsustainable fiscal autopilot:

The Medicare program is also grossly underfunded relative to its future obligations. And the fact that Medicare and Medicaid are entitlements means that spending grows on autopilot because Congress does not have to make annual appropriations to fund these programs.

Silver and Hyman explain that the best healthcare insurance system would be catastrophic coverage with deductibles:

[T]he problem is that spending on health care can vary greatly. All it takes is a bad case of trauma or an emergency surgery for appendicitis to move a person from the average category into the highest cost group—the 5 percent of Americans whose medical treatments account for 50 percent of total spending. The mean annual expenditure for that group is about $43,000. Making the top 10 percent of spenders, who collectively account for 66 percent of medical expenses, is even easier. The mean outlay for that group is only $28,500. There’s a lot of turnover in these high-cost groups too. Although nearly two-thirds of the members of the top 5 percent group suffer from long-term illnesses, every year about half of that share gets better and drops down to a lower bracket. Of course, this implies that lots of new people move into the high-cost group every year too. Many people think that this distribution of costs makes it impossible for health insurance to work. This position betrays a fundamental misunderstanding of insurance economics. It is precisely the potential for incurred costs to vary by several orders of magnitude that creates a demand for insurance and allows catastrophic coverage to do its job—by placing a ceiling on the amount that a person must spend out of pocket on needed medical services in any policy period. When spending exceeds the ceiling, the insurance policy kicks in and protects the consumer from much or all of the burden of any additional medical treatments. And, because so few people incur catastrophic health care expenses, catastrophic coverage is affordable—as long as it isn’t larded up with payments for predictable expenditures and cross-subsidies.

Finally, Silver and Hyman explain that:

[I]f you were trying to create a dynamic that would funnel ever-increasing amounts of money into the health care system, it would be hard to improve on Obamacare, which required everyone to have comprehensive insurance, backed up with huge amounts of federal funding to hide from everyone involved the true costs of running prepayment and welfare programs in the guise of an insurance program … Medicare is an intergenerational Ponzi scheme that moves dollars from younger people who are relatively poor to older people who are relatively rich, while making health care more dangerous and expensive for everyone and wasting one-third of the dollars it doles out. How can a moral case be made for a program like that? Medicaid helps the poor, but it does so inefficiently and is needlessly paternalistic. Poor people would fare better if the program was replaced with cash grants … When Medicare was created, there were 4.5 working people for every eligible beneficiary. Over time, the ratio has steadily declined. In 2016, there were only 3.1 workers per beneficiary. In 2030, there will be only 2.4. As the ratio of workers to beneficiaries falls, taxes per worker will have to rise.

That concludes this essay series on the American healthcare system.