Having explored in previous essays some barriers to scientific progress, including in the medical field, this series will explore some potential dysfunctions in how health care is delivered in America.

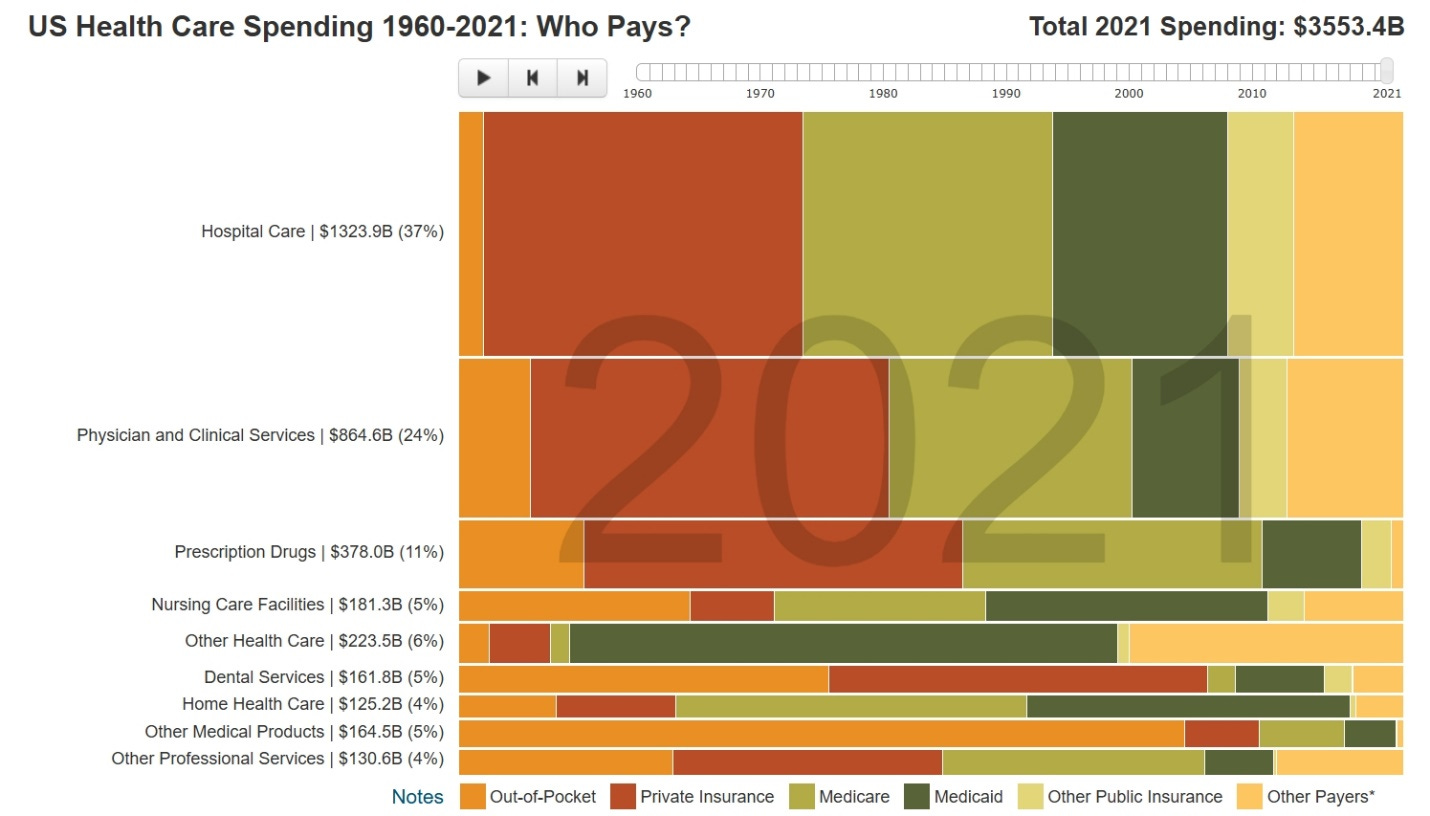

Since the 1960’s, the government has been paying more and more for individuals’ health care. As a result, the health care system is less accountable to individual consumers, who now increasingly rely on the government -- or government-mandated insurance provided by third parties -- to see that just about all their medical care is paid for, not just conditions that are major, rare, and unpredictable. (The less orange there is on the charts that follow, the more government and government-mandated insurance -- and not individual consumers – govern health care decisions.)

This chart shows the same growth in government spending on health care over the years, compared to private individual out-of-pocket spending.

Out-of-pocket health care spending as a fraction of per capita consumption is lower in the United States.

However, the more out-of-pocket spending there is in a country’s health care system, the lower its per-capita health care spending tends to be.

Why is that? It’s because when people don’t account for their spending on medical care, they are not requiring health care providers to compete for their money by lowering prices. As John Cochrane explains, “It is widely recognized that catastrophic insurance plus health savings plans are a much better structure than current pay for everything structures,” and “People really do not need health insurance for regular small expenses, as they do not need car insurance to "pay for" oil changes. And any insurance system relies on an underlying cash market to find what the right prices are. Collision insurance works reasonably well because there is a supply and demand market for auto repair in which people pay their own money and there are competitive suppliers and free entry, offering services along a wide quality-price spectrum.” However, “The underlying cash market has disappeared in health care. If you try to just pay for service, you face the ridiculous sticker prices. Everyone needs to go through some sort of middleman.”

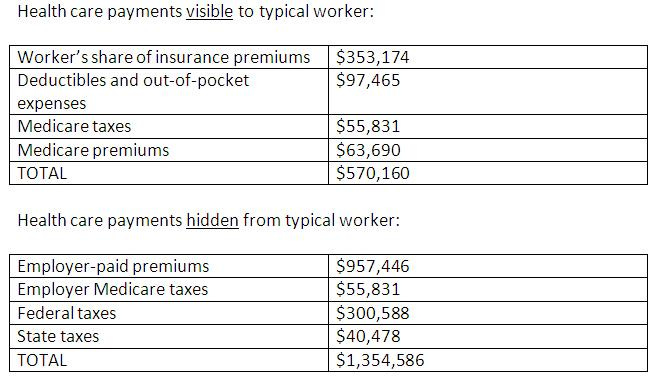

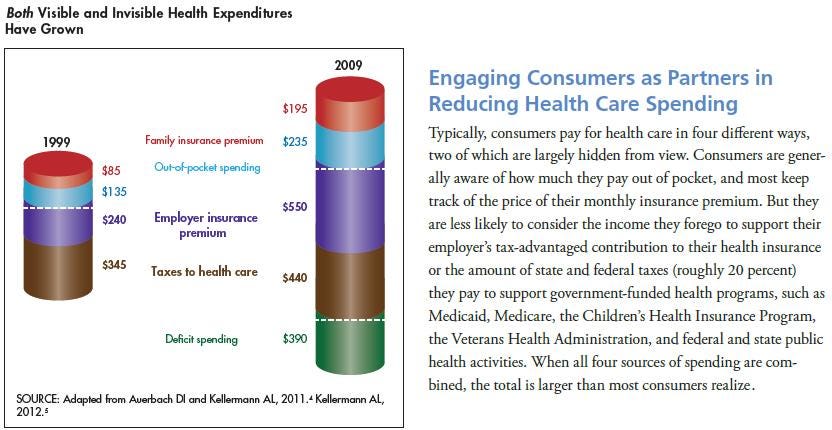

To illustrate the impact of this on a personal level, take the example of a woman who gets married at 30 and has two children, works until she is 65 and dies at 80, has an income that starts at $35,000 a year and increases by 4 percent a year so at retirement she is making $180,000 a year. Such a typical person only sees a small part of their health care expenses during their working years. The rest, which is paid by their employer or taken from taxes, remains invisible to them. The full cost of health care for this typical worker is actually $1.9 million over her lifetime.

And as health care costs rise, wages fall, as the more companies must pay in health care costs, the less they can pay in wages. Data show that when health care cost growth has slowed (as in the early 1990’s), wages crept up. But as cost growth increased, wages stagnated, and when health costs grew at a slower rate (as in the mid-2000’s), wages rebounded again.

Researchers at Stanford and Harvard have calculated that the Obamacare law’s mandate to cover adult children through age 26 on the insurance plans of their parents resulted in wage reductions, especially at large firms, of about $1,200 per year as employers needed to transfer that money to cover the extended health insurance of their employees. The study also found that the costs of the new mandate weren’t “only borne by parents of eligible children or parents more generally.” Rather, they’re spread over all workers including other young people, the childless and late middle-aged.

If more people could keep more of their health benefits costs as income, they would tend to have better health, as higher incomes are associated with better health. These “invisible” health care costs are very high because most people, including those covered under Obamacare (the Affordable Care Act), do not have health “insurance,” but rather pre-paid health plans that cover all medical expenses -- with hospital charges negotiated not by consumers themselves but by third party insurance companies.

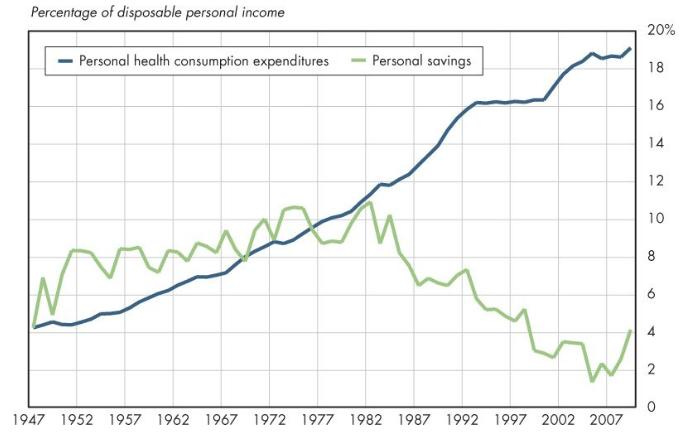

After the federal government became more involved in the provision of health care, personal health care consumption expenditures rose dramatically, and personal savings declined.

For context, the fifth most costly Medicare patient in the country in 2009 required $2.7 million in care for catastrophic events (see chart below). What this means is that under the current health care system, about $1.9 million is contributed by every worker, even though some of the most catastrophic actual risks cost around $3 million to address (and will affect only a very, very few during their lifetimes). The result is that too much money under the current system is spent unnecessarily managing non-catastrophic claims and associated administrative expenses.

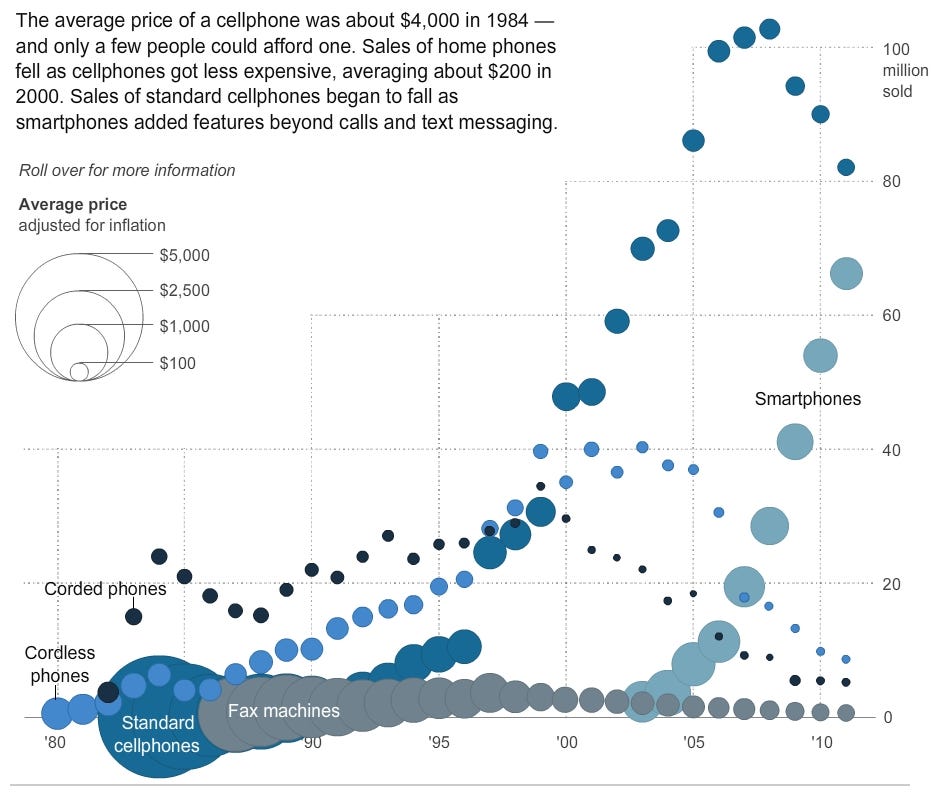

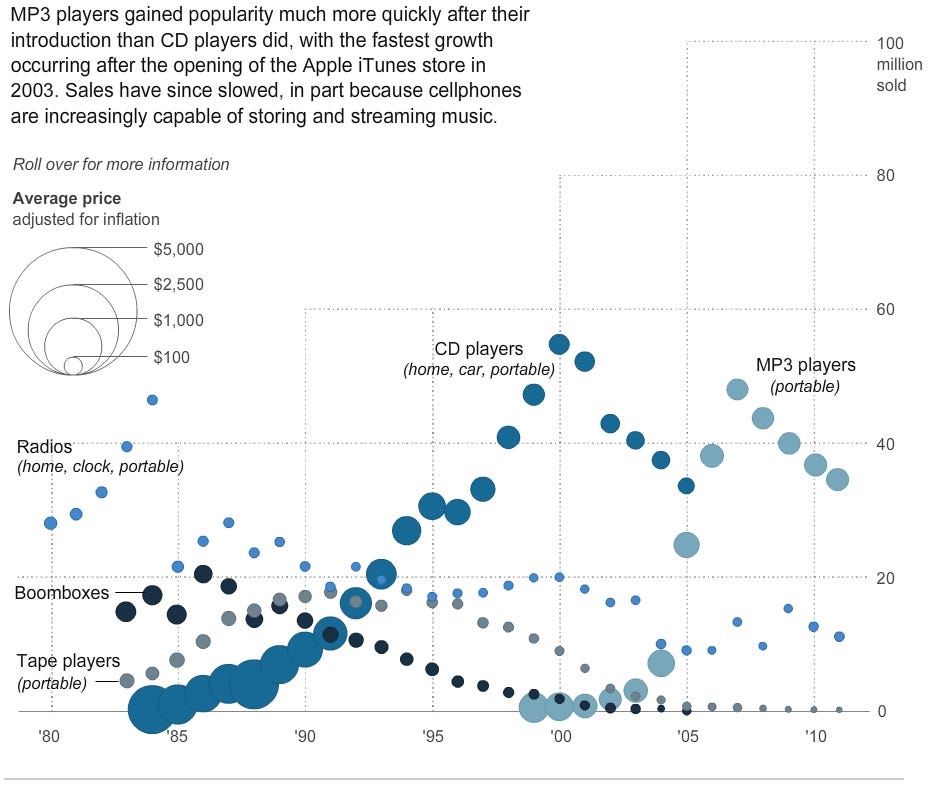

When just about all health care – and not just major, rare, and unpredictable conditions, which are much more reasonably covered by insurance – is paid for by third parties and not directly by consumers, health care is removed from a competitive pricing system that generally lowers costs as technology improves. This lowering of costs occurs in sectors of the economy not subject to significant government regulation, but not in health care, which is heavily regulated. As the graphics below illustrate, cell phones, personal computers, televisions, and MP3 players, for example, have all improved in quality and become cheaper over time, as those products are subject to competitive market forces. But health care is not. Consequently, routine medical care under the current system is much more expensive than it should be.

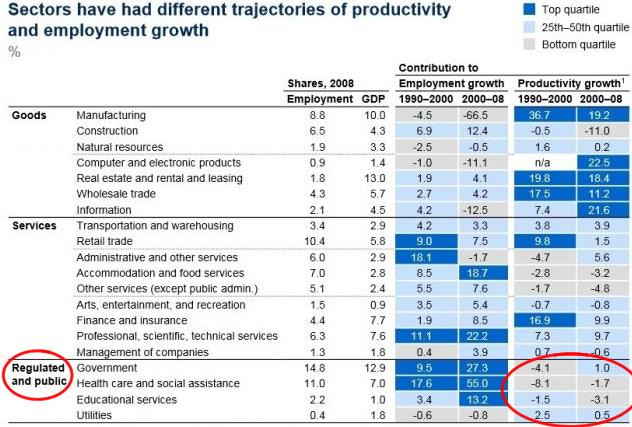

Public and regulated sectors such as healthcare and education represent more than 20 percent of the U.S. economy, but have persistently low productivity growth, especially compared to the very productive sectors that are generally unregulated by the government, and which provide better products at lower costs.

The medical consumer price index has grown much faster than the overall consumer price index.

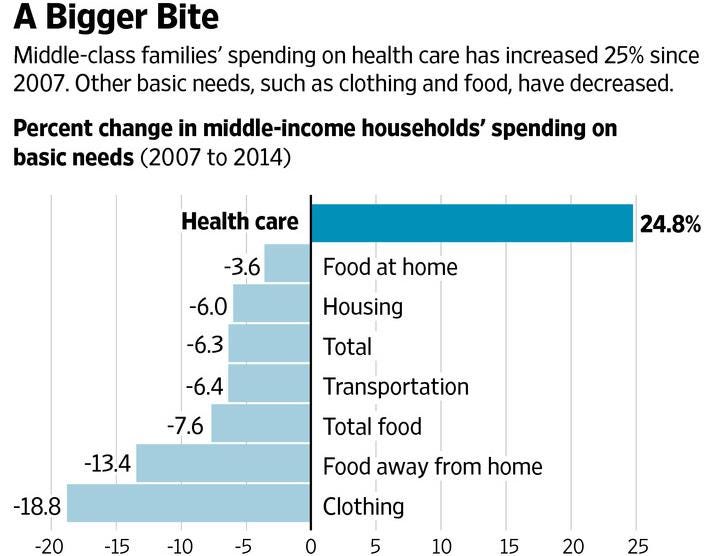

Since 2007, middle class family spending on health care has increased 25 percent, whereas spending on things not so heavily regulated by the government has gone down.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll continue to explore how paying less out-of-pocket for medical care leads to paying more for medical care overall.

Paul, Now writing to my sweet spot. This is already more-than-interesting and reinforces a speech about the disconnect of the individual from the whole health care system. This has an inverse effect (which you may get to) that is unrelated to pricing and efficiency/efficacy -- because the patient never actually directly pays for much of anything, the entire system (especially IT where I spend lots of time) is constructed around everything EXCEPT the patient -- putting together a record on a patient that is useful, useable and used is virtually impossible. This deprecates the quality of all care and is, by itself, likely responsible for $250B/year of wasted expense.

So important topic and your insights are already adding data to my stack that will be useful and used!

Many thanks.