The Adventures of a Revolutionary Soldier – Part 1

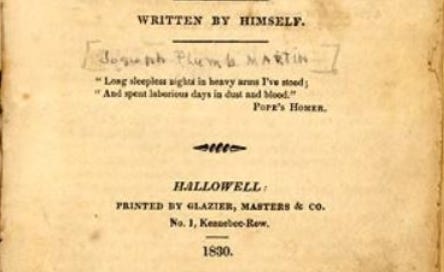

Joseph Plumb Martin’s fascinating Narrative of a Revolutionary Soldier.

Did you ever wonder what it was really like to serve as a soldier in the American Revolutionary War? There’s only one memoir of that experience written by someone other than a high-ranking officer — someone who experienced the war in all its lowly squalor firsthand. That memoir is Joseph Plumb Martin’s The Adventures of a Revolutionary Soldier. A friend of mine who’s writing a book on the composition of Revolutionary War regiments highly recommended I read it. I did, and now I realize every American should read it (or at least read the extended excerpts I’ll be providing in this series of essays). Joseph Martin didn’t have any formal schooling, but his narrative is mostly a joy to read. His commentary is plain-spoken using the language of the time, with touches of humor and insight that even today’s soldiers are bound to relate to in some way. The book makes one ponder, “What sorts of principles drove people to fight through and survive such conditions?” Leading up to this July 4, sit back and take in this uniquely descriptive narrative that will leave you with an even greater appreciation for the usually unheralded patriots who won our independence.

What follows are extended excerpts from Martin’s narrative, with only short explanatory transitions provided by me when necessary.

Martin begins his narrative by stating to readers that before them is “not the achievements of an officer of high grade,” but rather “the common transactions of one of the lowest in station in an army, a private soldier.” He continues:

[E]very private soldier in an army thinks his particular services as essential to carry on the war he is engaged in, as the services of the most influential general; and why not? what could officers do without such men? Nothing at all. Alexander never could have conquered the world without private soldiers … But, says the reader, this is low, the author gives us nothing but everyday occurrences; I could tell as good a story myself. Very true, Mr. Reader, every one can tell what he has done in his lifetime, but every one has not been a soldier, and consequently can know but little or nothing of the sufferings and fatigues incident to an army … But after all I have said, the real cause of my … undertaking to rake up circumstances and actions that have so long rested in my own mind, and to spread them upon paper, was this:— my friends, and especially my juvenile friends have often urged me so to do; to oblige such, I undertook it, hoping it might save me often the trouble of verbally relating them. The critical grammarian may find enough to feed his spleen upon, if he peruses the following pages; but I can inform him beforehand, I do not regard his sneers; if I cannot write grammatically, I can think, talk and feel like other men. Besides, if the common readers can understand it, it is all I desire; and to give them an idea, though but a faint one, of what the army suffered that gained and secured our independence, is all I wish.

Martin relates his upbringing as follows:

[M]y father was the son of a “substantial New England farmer,” (as we Yankees say,) in the then Colony, but now State of Connecticut, and county of Windham. When my father arrived at puberty he found his constitution too feeble to endure manual labor, he therefore directed his views to gaining a livelihood by some other means. He, accordingly, fitted himself for, and entered as a student in Yale College, sometime between the years 1750 and ‘55. My mother was likewise a “farmer’s daughter;” her native place was in the county of New-Haven, in the same State … I remember the stir in the country occasioned by the stamp act, but I was so young that I did not understand the meaning of it; I likewise remember the disturbances that followed the repeal of the stamp act, until the destruction of the tea at Boston and elsewhere; I was then thirteen or fourteen years old, and began to understand something of the works going on. I used, about this time, to inquire a deal about the French war, as it was called, which had not been long ended, my grandsire would talk with me about it while working in the fields, perhaps as much to beguile his own time as to gratify my curiosity. I thought then, nothing should induce me to get caught in the toils of an army—” I am well, so I’ll keep,” was my motto then, and it would have been well for me if I had ever retained it … The winter of this year passed off without any very frightening alarms, and the spring of 1775 arrived. Expectation of some fatal event seemed to fill the minds of most of the considerate people throughout the country. I sat off to see what the cause of the commotion was. I found most of the male kind of the people together; soldiers for Boston were in requisition. A dollar deposited upon the drum head was taken up by some one as soon as placed there, and the holder’s name taken, and he enrolled, with orders to equip himself as quick as possible. My spirits began to revive at the sight of the money offered; the seeds of courage began to sprout; for, contrary to my knowledge, there was a scattering of them sowed, but they had not as yet germinated; I felt a strong inclination, when I found I had them, to cultivate them. O, thought I, if I were but old enough to put myself forward, I would be the possessor of one dollar, the dangers of war to the contrary notwithstanding; but I durst not put myself up for a soldier for fear of being refused, and that would have quite upset all the courage I had drawn forth. This year there were troops raised both for Boston and New-York. Some from the back towns were billeted at my grandsire’s; their company and conversation began to warm my courage to such a degree, that I resolved at all events to “go a sogering.” … During the winter of 1775-6, by hearing the conversation and disputes of the good old farmer politicians of the times, I collected pretty correct ideas of the contest between this country and the mother country, (as it was then called.) I thought I was as warm a patriot as the best of them; the war was waged; we had joined issue, and it would not do to “put the hand to the plough and look back.” I felt more anxious than ever, if possible, to be called a defender of my country … One evening, very early in the spring of this year, I chanced to overhear my grandma’am telling my grandsire that I had threatened to engage on board a man-of-war. I had told her that I would enter on board a privateer then fitting out in our neighbourhood; the good old lady thought it a man-of-war, that and privateer being synonymous terms with her. She said she could not bear the thought of my being on board of a man-of-war; my grandsire told her, that he supposed I was resolved to go into the service in some way or other, and he had rather I would engage in the land service if I must engage in any. This I thought to be a sort of tacit consent for me to go, and I determined to take advantage of it as quick as possible. Soldiers were at this time enlisting for a year’s service; I did not like that, it was too long a time for me at the first trial; I wished only to take a priming before I took upon me the whole coat of paint for a soldier. However, the time soon arrived that gratified all my wishes. In the month of June, this year, orders came out for enlisting men for six months from the twenty-fifth of this month. The troops were … to go to New-York; and, notwithstanding I was told that the British army at that place was reinforced by fifteen thousand men.

Martin describes how his enlistment came about:

[S]eating myself at the table, enlisting orders were immediately presented to me; I took up the pen, loaded it with the fatal charge, made several mimic imitations of writing my name, but took especial care not to touch the paper with the pen until an unlucky wight who was leaning over my shoulder gave my hand a stroke, which caused the pen to make a woeful scratch on the paper. “O, he has enlisted,” said he, “he has made his mark, he is fast enough now.” Well, thought I, I may as well go through with the business now as not; so I wrote my name fairly upon the indentures. And now I was a soldier, in name at least, if not in practice … In the morning when I first saw my grandparents, I felt considerably of the sheepish order. The old gentleman first accosted me with, “Well, you are going a soldiering then, are you?” I had nothing to answer; I would much rather he had not asked me the question. I saw that the circumstance hurt him and the old lady too; but it was too late now to repent. The old gentleman proceeded,—”I suppose you must be fitted out for the expedition, since it is so.”—Accordingly, they did “fit me out” in order, with arms and accoutrements, clothing, and cake, and cheese in plenty, not forgetting to put my pocket Bible into my knapsack.—Good old people! … I went, with several others of the company, on board a sloop, bound to New-York … I was brought to an allowance of provisions, which, while we lay in New-York was not bad: if there was any deficiency it could in some measure be supplied by procuring some kind of sauce …

Martin makes some general points before beginning his account of the war:

I never wished to do any one an injury, through malice, in my life; nor did I ever do any one an intentional injury while I was in the army, unless it was when sheer necessity drove me to it, and my conscience bears me witness, that innumerable times I have suffered rather than take from any one what belonged of right to them, even to satisfy the cravings of nature. But I cannot say so much in favour of my levity, that would often get the upper hand of me, do what I would; and sometimes it would run riot with me; but still I did not mean to do harm, only recreation, reader, recreation; I wanted often to recreate myself, to keep the blood from stagnating.

Martin then describes how reality began to set in:

We soon landed at Brooklyn, upon the Island, marched up the ascent from the ferry, to the plain. We now began to meet the wounded men, another sight I was unacquainted with, some with broken arms, some with broken legs, and some with broken heads. The sight of these a little daunted me, and made me think of home, but the sight and thought vanished together … Whether we had any other victuals besides the hard bread I do not remember, but I remember my gnawing at them; they were hard enough to break the teeth of a rat … [T]he Americans and British were warmly engaged within sight of us. What were the feelings of most or all the young soldiers at this time, I know not, but I know what were mine;—but let mine or theirs be what they might, I saw a Lieutenant who appeared to have feelings not very enviable; whether he was actuated by fear or the canteen I cannot determine now; I thought it fear at the time; for he ran round among the men of his company, snivelling and blubbering, praying each one if he had aught against him, or if he had injured any one that they would forgive him, declaring at the same time that he, from his heart, forgave them if they had offended him, and I gave him full credit for his assertion; for had he been at the gallows with a halter about his neck, he could not have shown more fear or penitence. A fine soldier you are, I thought, a fine officer, an exemplary man for young soldiers! I would have then suffered any thing short of death rather than have made such an exhibition of myself; but, as the poet says, “Fear does things so like a witch, “‘Tis hard to distinguish which is which” …

Martin describes his first military engagement:

While we were resting here our Lieutenant-Colonel and Major, (our Colonel not being with us,) took their cockades from their hats; being asked the reason, the Lieutenant-Colonel replied, that he was willing to risk his life in the cause of his country, but was unwilling to stand a particular mark for the enemy to fire at. He was a fine officer and a brave soldier … We overtook a small party of the artillery here, dragging a heavy twelve pounder upon a field carriage, sinking half way to the naves in the sandy soil. They plead hard for some of us to assist them to get on their piece; our officers, however, paid no attention to their entreaties, but pressed forward towards a creek, where a large party of Americans and British were engaged. By the time we arrived, the enemy had driven our men into the creek, or rather mill-pond, (the tide being up,) where such as could swim got across; those that could not swim, and could not procure any thing to buoy them up, sunk. The British having several fieldpieces stationed by a brick house, were pouring the cannister and grape upon the Americans like a shower of hail; they would doubtless have done them much more damage than they did, but for the twelve pounder mentioned above; the men having gotten it within sufficient distance to reach them, and opening a fire upon them, soon obliged them to shift their quarters. There was in this action a regiment of Maryland troops, (volunteers,) all young gentlemen. When they came out of the water and mud to us, looking like water rats, it was a truly pitiful sight. Many of them were killed in the pond, and more were drowned. Some of us went into the water after the fall of the tide, and took out a number of corpses and a great many arms that were sunk in the pond and creek … The next day the British showed themselves to be in possession of our works upon the island, by firing upon some of our boats, passing to and from Governor’s Island. Our regiment was employed, during this day, in throwing up a sort of breastwork, at their alarm post upon the wharves, (facing the enemy,) composed of spars and logs, and filling the space between with the materials of which the wharves were composed,—old broken junk bottles, flint stones, &c. which, had a cannon ball passed through, would have chanced to kill five men where the ball would one. But the enemy did not see fit to molest us … These British soldiers seemed to be very busy in chasing some scattering sheep, that happened to be so unlucky as to fall in their way. One of the soldiers, however, thinking, perhaps, he could do more mischief by killing some of us, had posted himself on a point of rocks, at the southern extremity of the Island, and kept firing at us as we passed along the bank. Several of his shots passed between our files, but we took little notice of him, thinking he was so far off that he could do us but little hurt, and that we could do him none at all, until one of the guard asked the officer if he might discharge his piece at him; as it was charged and would not hinder us long, the officer gave his consent. He rested his old six feet barrel across a fence and sent an express to him. The man dropped, but as we then thought it was only to amuse us, we took no further notice of it but passed on. In the morning, upon our return, we saw the brick coloured coat still lying in the same position we had left it in the evening before: it was a long distance to hit a single man with a musket, it was certainly over half a mile … In retreating, we had to cross a level clear spot of ground, forty or fifty rods wide, exposed to the whole of the enemy’s fire; and they gave it to us in prime order; the grape shot and langrage flew merrily, which served to quicken our motions. When I had gotten a little out of the reach of their combustibles, I found myself in company with one who was a neighbour of mine when at home, and one other man belonging to our regiment; where the rest of them were I knew not. We went into a house by the highway, in which were two women and some small children, all crying most bitterly; we asked the women if they had any spirits in the house; they placed a case bottle of rum upon the table, and bid us help ourselves. We each of us drank a glass, and bidding them good bye, betook ourselves to the highway again … When we came off the field we brought away a man who had been shot dead upon the spot; and after we had refreshed ourselves we proceeded to bury him. Having provided a grave, which was near a gentleman’s country seat, (at that time occupied by the Commander-in-chief,) we proceeded, just in the dusk of evening, to commit the poor man, then far from friends and relatives, to the bosom of his mother earth. Just as we had laid him in the grave, in as decent a posture as existing circumstances would admit, there came from the house, towards the grave, two young ladies, who appeared to be sisters;—as they approached the grave, the soldiers immediately made way for them, with those feelings of respect which beauty and modesty combined seldom fail to produce, more especially when, as in this instance, accompanied by piety. Upon arriving at the head of the grave, they stopped, and, with their arms around each other’s neck, stooped forward and looked into it, and with a sweet pensiveness of countenance which might have warmed the heart of a misogamist, asked if we were going to put the earth upon his naked face; being answered in the affirmative, one of them took a fine white gauze handkerchief from her neck and desired that it might be spread upon his face, tears, at the same time, flowing down their cheeks. After the grave was filled up they retired to the house in the same manner they came. Although the dead soldier had no acquaintance present, (for there were none at his burial who knew him,) yet he had mourners, and females too.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll explore more of Joseph Plumb Martin’s A Narrative of a Revolutionary Soldier, including his descriptions of the extraordinarily harsh conditions of the war.

Paul, Well this is out of left field but fascinating. I look forward to reading your excerpts because I am unlikely to find time to read the whole book. Thanks for making another day unexpectedly interesting!