Thanksgiving Week -- So You Think Your Life is Tough? Check Out Life in Early America – Part 3

What changing a diaper was like, and exponential growth in fecal matter.

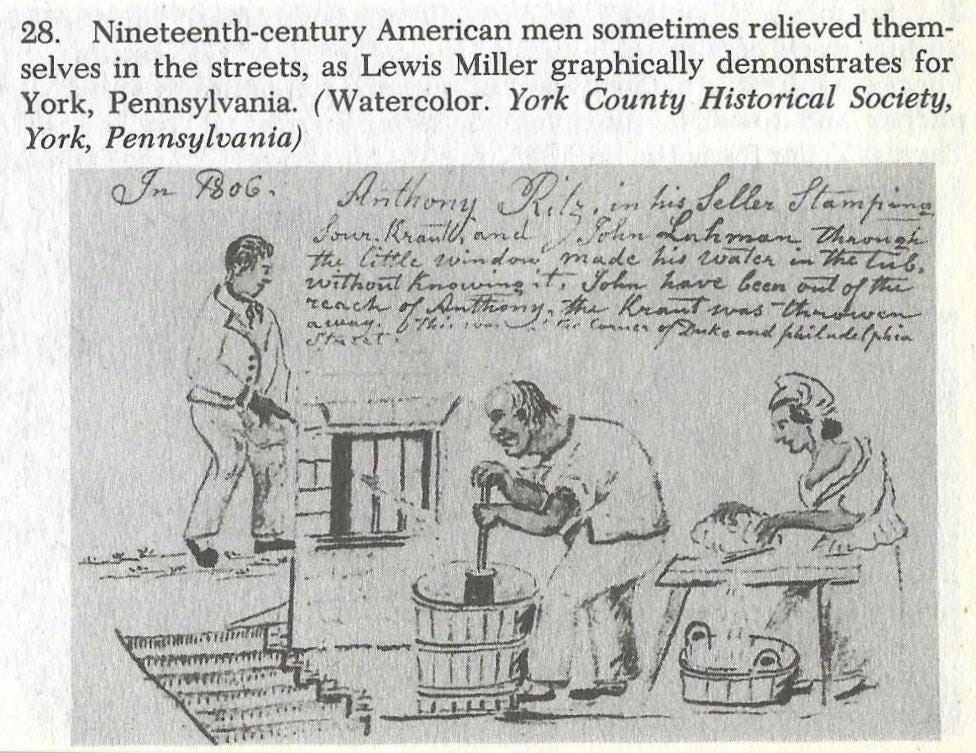

Still not feeling thankful enough for your life today? Well let’s explore just how abjectly filthy everything was not too long ago.

Filthy living conditions

In a previous essay we discussed the dramatic improvements in lighting since colonial times. Well, back then, people may not have wanted to see the squalor they lived in any more clearly. As Jack Larkin describes in his book The Reshaping of Everyday Life: 1790-1840:

Open fireplaces, dirt roads and the proximity of the barnyard meant that the houses of the early nineteenth century were inevitably dusty and dirty; without window screens, every room was full of flies and flyspecks in summer … Inundated with the daily tasks of farm households, rural women sometimes struggled with dirt, and more often ignored it. Travelers found dirt and litter on the floors, and household belongings in disorderly piles. In the countryside, the archaeological record shows, housewives still tossed broken vessels and trash out the most convenient door or window, and threw bones and food scraps into the yard to be picked over by their pigs and chickens. Patterns of convenient use clearly governed, not concern for the look of the domestic landscape. In the first two decades of the nineteenth century the great majority of American families had not yet come to see the environment immediately around the house as anything but a workspace … Early nineteenth-century Americans lived in a world of dirt, insects and pungent smells. Farmyards were strewn with animal wastes, and farmers wore manure-spattered boots and trousers everywhere. Men’s and women’s working clothes alike were often stiff with dirt and dried sweat, and men’s shirts were often stained with yellow rivulets of tobacco juice. The location of privies was all too obvious on warm or windy days, and unemptied chamber pots advertised their presence. Wet baby “napkins,” today’s diapers, were not immediately washed but simply put by the fire to dry.

That’s right: in colonial times, not only did parents use a cloth diaper on their children, but due to the lack of running water they just hung up dirty diapers to dry so they could later beat out the dried remnants and put the same diaper back on their kids.

And when a cleaning agent was used, what exactly was it? Larkin continues:

Vats of “chamber lye”—highly concentrated urine used for cleaning type or degreasing wool—perfumed all printing offices and many households.

Yup, they used urine to clean things. When they cleaned things at all. More Larkin:

“The breath of that fiery bar-room,” as [Francis] Underwood described a country tavern, “was overpowering. The odors of the hostlers’ boots, redolent of fish-oil and tallow, and of buffalo-robes and horse-blankets, the latter reminiscent of equine ammonia, almost got the better of the all-pervading fumes of spirits and tobacco.” Densely populated, but poorly cleaned and drained, America’s cities were often far more noisome than its farmyards. City streets were thickly covered with horse manure and few neighborhoods were free from the spreading stench of tanneries and slaughterhouses. New York City’s accumulation of refuse was so great that it was generally believed that the actual surfaces of many streets had not been seen for decades. During her stay in Cincinnati, Frances Trollope thought she was following the practice of American city housewives when she threw her household “slops”—refuse food and dirty dishwater—out into the street. An irate neighbor soon informed her that municipal ordinances forbade “throwing such things at the sides of the streets” as she had done; “they must just all be cast right into the middle and the pigs soon takes them off.” In most cities hundreds or even thousands of free-roaming pigs scavenged the garbage; one exception was Charleston, whose streets were patrolled by buzzards.

Back then, you would throw your trash in the street so animals could convert it to feces, which was then deposited back on the street.

Spitting

Fecal matter everywhere not bad enough? Add spit to the mix. As Larkin writes:

“In all the public places of America,” winced Charles Dickens, multitudes of men engaged in “the odious practice of chewing and expectorating.” Chewing stimulated salivation, and gave rise to a public environment of frequent and copious spitting, where men every few minutes were “squirting a mouthful of saliva through the room.” The scenes, indoors and out, created by large groups of men with chaws in their cheeks are still difficult to reconstruct without distaste. Spittoons were provided in the more meticulous establishments, but men often ignored them, and more frequently they were missing entirely. The floors of American public buildings were not pleasant objects to contemplate. Thomas Hamilton found a courtroom in New York City in 1833 decorated by a “mass of abomination” produced by “judges, counsel, jury, witnesses, officers, and audience.” The floor of the Virginia House of Burgesses, said Margaret Hall in 1827, was “actually flooded with their horrible spitting,” and even the aisles of some churches were black with the “ejection after ejection, incessant from twenty mouths,” of the men singing in the choir. In order to drink, an American man might remove his quid, put it in a pocket or hold it in his hand, take his glassful, and then restore it to his mouth.

Shoes

Back then, at least you had shoes to protect yourself from the filth. Or maybe not:

Another highly visible line separated the shod and the barefoot. “I had no shoes until the ground began to freeze,” [Asa] Sheldon recalled, summarizing generations of experience in the countryside; those he did wear were usually vastly oversized and had to be stuffed with rags, since they were made to last him for two or three years. Even crude footwear was costly enough so that among poor and middling families children and many adults went unshod except in cold weather. Barefoot men driving teams and shoeless women working in their gardens could be seen almost everywhere.

Small living quarters

Today, people move to more rural areas to enjoy larger living quarters. But back in colonial times, tiny homes were the norm in even in the middle of nowhere. As Larkin writes:

The single-room house—in which almost all medieval Europeans had lived, and contemporary African villagers still did—remained a reality for many early nineteenth-century Americans. The households of most slaves, some poorer whites and many new settlers lived “corporately,” carrying out all the activities of life in sight and hearing of one another. Slaves lived most densely of all, sometimes putting two families in one room … Such houses did not have physical partitions, but spaces set aside for sleeping, eating, working and socializing, with unmarked but perceptible boundaries. A North Carolina white family living in a single-room house in the 1830s cooked and ate around the fireplace at the end of the house farthest away from the door. Their beds were in another corner, and opposite them was the space for sitting and entertaining, furnished with a clock and chairs.

Today, there’s concern over the psychological harm caused by living in tight quarters -- but at least today, those tight quarters aren’t filled with dirt and smoke.

Weather and astrology dominated conversation

And what was there to talk about back in the day? Well, if you think talking about the weather’s worse than awkward silence, in early America the weather was just about all farmers talked about. As Larkin writes, “The most common currency of American conversation was talk of the agricultural year, with its anxious scanning of the weather and concern for crops, livestock and new or worn-out tools.”

And when people weren’t talking about the weather, they were talking about what a widely superstitious people at the time associated with the weather, namely the power over events of the phases of the moon, and of astrological predictions:

For men and women who worked daily with plants and animals, the natural cycles of growth and procreation were still powerful mysteries, governed at least in part by the phases of the moon and the great celestial wheel of the zodiac. Rural folk “believed that many things must be done, or left undone, during the reign of each constellation,” recalled the Cincinnati physician Daniel Drake of his Kentucky boyhood, and that “the moon had a powerful influence on vegetation and animal life.” Women planted radishes in their gardens “downward at the decrease of the moon, for they tapered downwards.” Some crops had to be planted at the dark of the moon and still others while it was waxing toward full.

So whenever you’re feeling bummed out when performing any of the more mundane aspects of life (like making kids’ lunches) be thankful that at least you don’t feel compelled to place the chips and the sandwich in a specific way in accordance with the position of the stars and the moon.

Transportation

In colonial times, when you traveled long distance, you were in for an extended battering. As Larkin writes:

The American stages of the 1790s were simply large freight wagons, with boxes built on top to accommodate passengers, and neither springs nor braces to damp down their jolting. Seated on backless benches, the passengers all faced forward, and entered from the front by scrambling over the seats.

Beds

And at the end of the day, after a long day of backbreaking work, you would lay your head to rest. Except it was more like scraping your head on broom bristles:

The greatest social gulf in sleeping furniture was between sleeping on feathers, a sign of at least modest comfort, and bedding down year-round on a straw tick, a scratchy and uncomfortable reminder of poverty … The urban poor … slept on straw mattresses in “habitations,” as a minister described the quarters of the poor in Massachusetts cities, “not ventilated at all,” with entire families “in a single room, and sometimes in one bed.” During the day they sat on their beds, or eked out a couple of old chairs with a broken barrel or two.

So in the span of around eight generations, we went from what’s been discussed in the last few essays to … just look around! Progress has brought us so far that today Thanksgiving should probably last a week. Stay thankful, everyone.