Continuing this series of essays on how teachers unions influence American public schools, in this essay we’ll examine teachers unions’ opposition to charter schools and school choice programs.

Teachers generally follow the union line of opposing school choice programs for parents and children and charter schools (which are public schools but not subject to union-supported administrative rules).

“Charter schools” are interesting case studies because they are public-funded schools, except they are allowed to operate independently of the local school system, including independently of its union rules. (Only just a few years ago, I realized the public high school I attended, the Norwich Free Academy, was essentially the nation’s first, or certainly one of the first, charter schools in America, founded in 1854 as a school publicly funded but independent of the local school system, and it remains independent of the local school system even today.)

As Terry Moe writes in his book Special Interest: Teachers Unions and America’s Public Schools:

Their opinions follow their self-interest, with 75 percent of all teachers saying they oppose vouchers for disadvantaged families … Some 58 percent of all teachers likewise oppose charter schools. Among union members, opposition is almost two to one, with 64 percent opposed. Even most Republican union members are opposed. But among teachers who don't belong to unions, 59 percent actually support charter schools, with support reasonably high among Democrats (55 percent) as well as Republicans (63 percent). Why the difference? We can't definitively know, but a reasonable explanation is that the connection between charter schools and teacher interests is somewhat ambiguous; charters are a threat, yes, but they also offer attractive alternatives for teachers themselves. This being so, teachers need to sort this through and get a sense of where the balance lies, and the unions help them do that by framing the issue in a distinctive way: by emphasizing that charters are a serious threat to the public schools (and teachers). Teachers who belong to unions, then, whether they are Democrat or Republican, come to see charters as contrary to their own interests. Teachers outside unions, who are largely free of this negative framing, often see charters in a much more positive light.

And as Philip Howard writes in his book Not Accountable: Rethinking the Constitutionality of Public Employee Unions:

Nowhere does union influence warp vital social policy more than in education. Education policy is largely driven by teachers unions, whose main interest is protecting teachers, not preparing students. They not only demand control, unaccountability, and increased funding, but they also resist initiatives to create alternative schools that many parents want. The poor performance in inner-city schools, the teachers unions say, is caused by forces beyond their control. Pathetic performance it surely is: Sixth graders in the poorest district are four grade levels below students in best school districts. While these differences are not solely caused by ineffective schools, bad schools bear much of the blame. We know this because nonunionized charter schools in the same districts, with students typically chosen by lottery, show dramatically superior results.

As Howard continues:

Economist Thomas Sowell reviews recent data for New York charter schools that share buildings with public schools. In 70 percent of the classes in KIPP charter schools, a majority of students scored proficient or better in English language arts; the comparable number was 5 percent in the public schools in the same buildings. The math differential was even higher. At Success Academy, a charter school network in Harlem, over three-quarters of students in each of thirty grade levels (the total from several schools) scored at “proficient” or better in English language arts. In a third of the classes, a majority scored “above proficient”—the highest category. In only three of thirty-six grade levels did the adjoining public schools manage a “proficient” rating for majority of students. Not one public school class had a majority of students scoring “above proficient.” In 2019, Success Academy 2 in Harlem was ranked thirty-seventh out of all elementary schools in New York State. The public school it shares a building with, PS 30, which serves a third as many kids and spends over twice as much per pupil, was ranked 1,694th. What is different about Success Academy? [Journalist] Steven Brill concluded that its educators were not shackled to union contracts and prerogatives.

The latest research on charter schools shows clear improvements in educational outcomes over traditional public schools. As Jonathan Chait reports in New York Magazine:

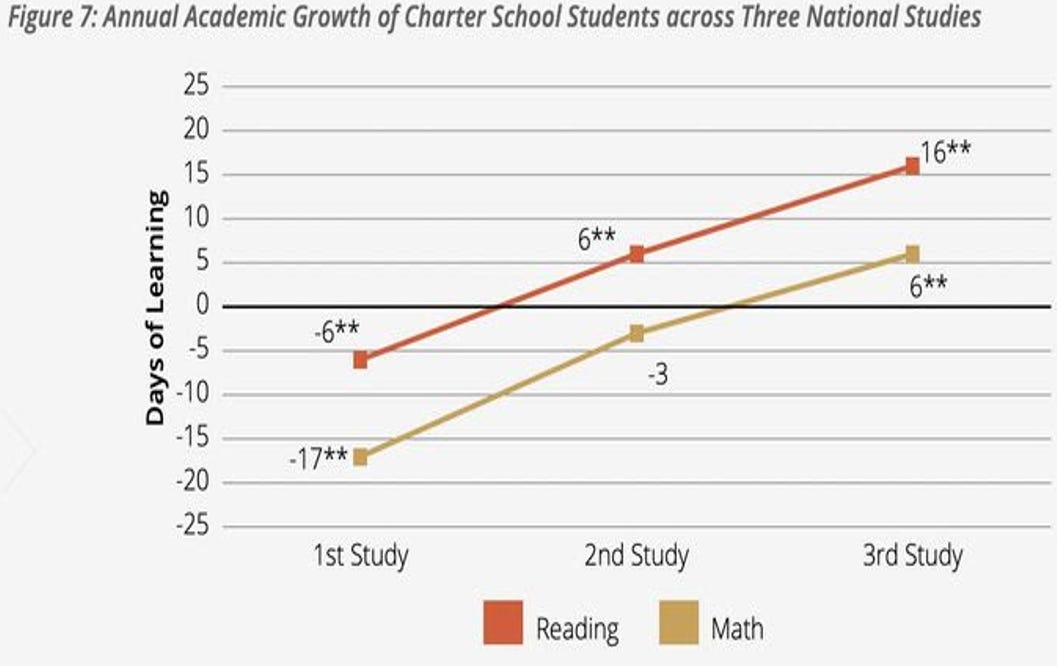

In 2009, a national study by Stanford’s Center for Research on Educational Outcomes, or CREDO, found that charter schools do not produce better outcomes than traditional public schools. If you have ever come across a column denouncing charter schools, you have probably seen a reference, either direct or indirect, to this finding … But this finding is badly out of date. A few years ago, Margaret Raymond, CREDO’s director, told me that its studies of states and districts were noting a distinct upward trend line in charter schools, especially those located in cities. At the time, CREDO had not conducted a national study since 2013. But now the center has released its latest report, and it confirms the trend Raymond had already seen locally. The new study finds, unambiguously, that students on average gain more learning in charter schools than in traditional public schools. What happened since 2009? Simply, charter schools got better. This chart shows the overall trend in charter schools from CREDO’s first study, in 2009, to its 2013 follow-up, to its latest:

The entire purpose of the charter-school model was to encourage experimentation with different models so that the best models could be tested and spread. The first charter school opened barely more than three decades ago, so it is hardly a surprise that it has taken time for educators to determine best practices. I’ve found even highly educated people who are not specialists in this field don’t understand how studies of charter schools work. When they hear charter schools produce learning gains, they assume those studies simply make unweighted comparisons of the test results of charter-school students against students in traditional public schools. That would be a terribly inaccurate way to measure the effect of a charter school, since it would leave open the possibility that charter schools simply enroll smarter or more motivated students. Instead, researchers employ a couple methods to separate the effect of the school from any differences in students. One method is lottery studies. Charter schools, unlike private schools, can’t select their students, and if they have more applicants than spaces, they must dole out spaces by random selection. Scholars have used these lotteries to measure the differences in outcomes between winners and losers … CREDO finds that a given student is now likely to learn more in a charter school than a demographically identical student in a traditional public school … Many of these charter networks can consistently allow low-income urban students to wipe out the achievement gap. This passage from CREDO’s study shows how powerful and widespread these effects can be: “More than 1,000 schools have eliminated learning disparities for their students and moved their achievement ahead of their respective state’s average performance. We refer to these schools as ‘gap-busting’ charter schools. They provide strong empirical proof that high-quality, high-equality education is possible anywhere. More critically, we found that dozens of CMOs have created these results across their portfolios, demonstrating the ability to scale equitable education that can change lives.” This is not just a handful of exceptional schools here and there. A large number of charter schools have developed scalable models that can allow Black and Latino students in cities with awful neighborhood schools to get the same education as white kids in suburbs enjoy … It is difficult for me to understand why, in the face of evidence that charter schools can make such a large difference for this neglected cohort, they are so often met with fatalism or antipathy. Opposition by teachers unions, which is rooted in charter schools’ need to circumvent union contracts that make it difficult to fire ineffective educators, has entrenched itself as the official progressive line on the subject; just as most progressive organs will trust pro-choice organizations on abortion and climate activists on the environment, so too will they generally defer to teachers unions on education reform.

As the Wall Street Journal reports:

Credo’s judgment is unequivocal: Most charter schools “produce superior student gains despite enrolling a more challenging student population.” In reading and math, “charter schools provide their students with stronger learning when compared to the traditional public schools.” The nationwide gains for charter students were six days in math and 16 days in reading. The comparisons in some states are more remarkable. In New York, charter students were 75 days ahead in reading and 73 days in math compared with traditional public-school peers. In Illinois they were 40 days ahead in reading and 48 in math. In Washington state, 26 days ahead in reading and 39 in math. Those differences can add up to an extra year of learning across an entire elementary education.

Teachers unions oppose charter schools, of course, because they are allowed to operate free of union rules. As Howard writes, “State by state, teachers unions have succeeded in capping the number of charter schools.” Interestingly, however, the Wall Street Journal recently highlighted that while Randi Weingarten, the head of the American Federation of Teachers union, supports charter schools run by teachers unions, she opposes other charter schools that would operate beyond union control:

It’s no secret that Randi Weingarten opposes co-locating charter schools in buildings that have a district public school. [My note: no doubt because the contrast between charter and public school student performance is on display so dramatically when they are co-located]. But the president of the American Federation of Teachers sits on the board of University Prep Charter Schools—a charter run by the local teachers union. On Wednesday New York’s Department of Education approved University Prep Charter’s bid for a permanent co-location for its middle school with a district school and another charter school. The backdrop points to the stunning hypocrisy … This year the unions have succeeded in pressuring Mayor Eric Adams to cancel three co-location proposals for Success Academy charter schools by ginning up opposition. Success Academy is one of the city’s best-performing charter networks … [T]he unions object only when co-location is for a school that unions don’t control. If you are a union charter school, with Randi Weingarten on your board, you expect—and get—the red carpet treatment. Membership sure has its privileges.

As Moe writes:

The Detroit public schools are among the worst in the nation. If any city's children are desperately in need of new educational alternatives, Detroit's are. Recognizing as much, a philanthropist offered in 2006 to put up $200 million of his own money to fund fifteen new charter high schools in that city. A gift of this magnitude would have been manna from heaven, and stood to be enormously beneficial to these inner city kids. Indeed, given what the future normally holds for these children, it may even have saved some of their lives — literally. But the local teachers union, rather than welcoming the gift with open arms, went ballistic. It shut down the Detroit schools for a day, sent its members to demonstrate outside the state capitol in Lansing, and convinced the politicians there to turn down the $200 million. The free money was lost. The fifteen charter schools were never built. Needless to say, had the philanthropist sought to build fifteen regular public schools, filled with unionized teachers and covered by collective bargaining, there would have been no controversy at all. His sin was to fund autonomous charter schools. And to threaten union jobs. That children might benefit was simply not part of the union's political equation.

Sometimes it takes a natural disaster to reset the table so charter schools have a place at the table. As Howard writes, “After Hurricane Katrina forced the closing of schools in New Orleans, however, the public school system was replaced by independent charter schools no longer subject to teachers union collective bargaining agreements. The differences were transformative. It was as if someone switched on the light. High school graduation rates improved from 52 to 72 percent, and gaps between racial groups narrowed.”

Teachers unions also oppose other publicly-funded alternatives to union-controlled public schools. As Howard explains:

Teachers unions also vociferously oppose “parent choice”—for example, providing vouchers that can be used at parochial or private schools … In California in 2000, the teachers unions spent $21 million to defeat another initiative to allow vouchers. To defeat a proposal for vouchers in Utah in 2007, Terry Moe found, “virtually every penny of the money was contributed by the teachers unions,” including “from teachers unions in other states—California, Washington, Colorado, Illinois, New Jersey, Kentucky, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Ohio. Their PAC was named Utahns for Public Schools.

As Frederick Hess writes in The Great School Rethink:

Outside school, we take for granted that families will choose childcare providers, pediatricians, dentists, babysitters, and summer programs. Indeed, many such choices involve parents or guardians making decisions that are subsidized by government funds. And the choices they make will have big implications for their child’s health, well-being, upbringing, and education. All of this tends to be regarded as wholly unexceptional … “What if parents make bad choices?” It’s an important question. But it should be considered in context. As we’ve noted, parents routinely make all manner of choices on behalf of their kids, from choosing a doctor or babysitter to managing screen time and bedtime. Parents may be imperfect choosers, but we generally trust that their judgments will be reasonable ones—and better than any practical alternative. Of course, even with terrific information, parents can still make bad choices about schooling. But that’s true of pretty much anyone involved in schools: teachers can make bad choices when deciding how to support a struggling student or designing an individualized education program. Administrators can make bad choices when meting out discipline or assigning a student to a teacher. Schooling is suffused with choices. We should certainly ask what happens when a parent makes a poor choice. But we must also question the consequences of restrictive policies that limit parents’ ability to find better educational options for their kids.

Recent research from the University of Chicago has also shown large benefits from public school choice programs. As the researchers write:

Does a school district that expands school choice provide better outcomes for students than a neighborhood-based assignment system? This paper studies the Zones of Choice (ZOC) program, a school choice initiative of the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) that created small high school markets in some neighborhoods but left attendance-zone boundaries in place throughout the rest of the district … Student outcomes in ZOC markets increased markedly, narrowing achievement and college enrollment gaps between ZOC neighborhoods and the rest of the district. The effects of ZOC are larger for schools exposed to more competition, supporting the notion that competition is a key channel. Demand estimates suggest families place substantial weight on schools' academic quality, providing schools with competition-induced incentives to improve their effectiveness. The evidence demonstrates that public school choice programs have the potential to improve school quality and reduce neighborhood-based disparities in educational opportunity.

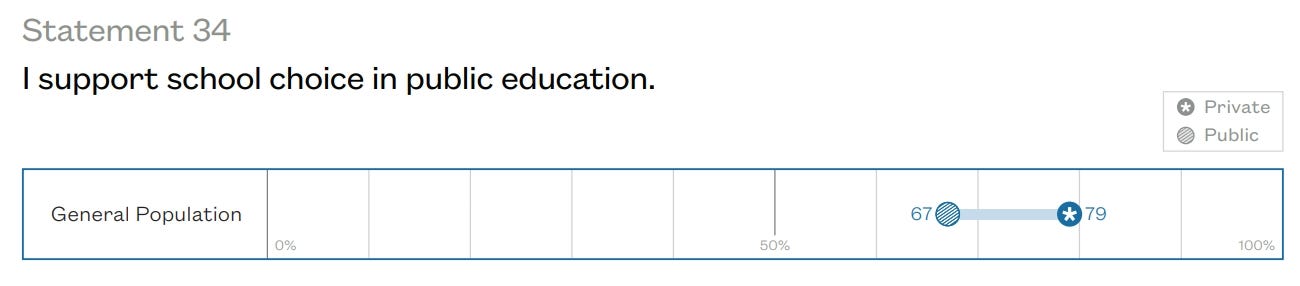

A think tank called Populace puts together the Social Pressure Index (SPI), which is based on a private opinion research study that reveals Americans’ true opinions about sensitive topics from a nationally representative sample of American adults, including more than 19,000 completed responses. It estimates the gap between Americans’ privately held beliefs and their publicly stated opinions. Regarding school choice, the survey found it is overwhelmingly popular with Americans. As the report states:

Most Americans believe that parents should be able to use public funds to access schools beyond their local public options. The Social Pressure Index brings greater clarity to this issue. While two out of three Americans publicly support school choice (67%), nearly four out of five privately agree (79%).

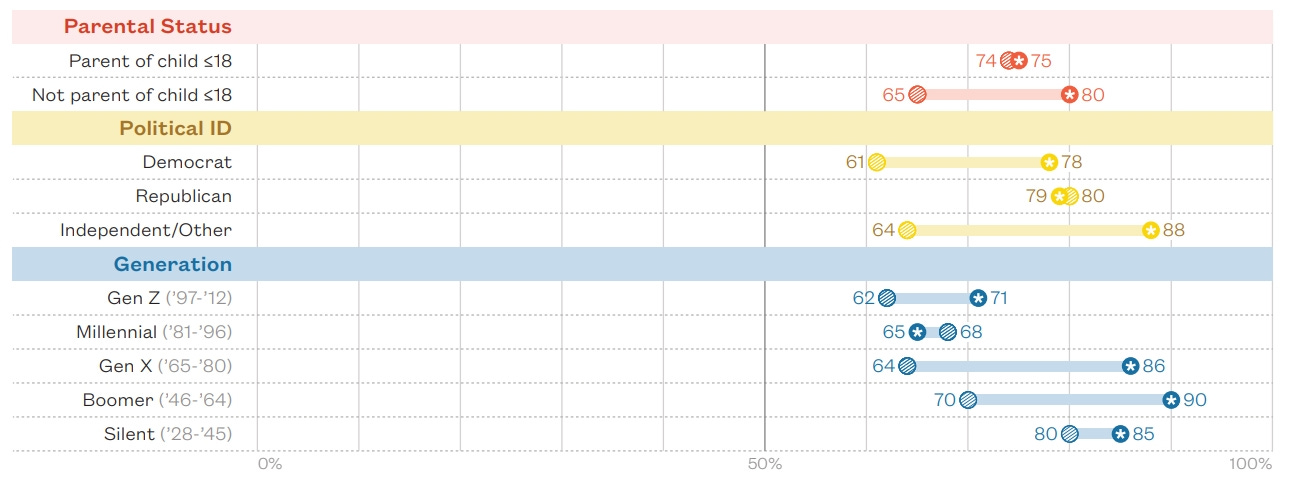

Notably, private support for school choice is similar regardless of whether respondents have school-aged children or not. Both publicly (74% agreement) and privately (75% agreement), parents with children under the age of 18 support school choice. A majority (65%) of people who do not have young children also publicly support school choice but feel even more supportive of the idea in private (80% agreement). Though school choice often surfaces as a political issue, in reality it receives overwhelming support across political affiliations, with a majority of Democrats (61%), Independents (64%), and Republicans (80%) publicly expressing agreement with the idea. Among both Democrats and Independents, private support is even higher (78% and 88%, respectively), with agreement among Independents outpacing that of Republicans. A similar trend can be seen across generations. A majority of Americans support school choice but tend to publicly underreport how they actually feel in private. Gen X (64% public, 86% private) and Boomers (70% public, 90% private) show the largest gap between public and private agreement on this topic.

But as Moe writes:

To the teachers unions, however, choice is deeply threatening. In fact, it is much more threatening than accountability is. When families are able to seek out new options—charter schools, for example, or possibly (with the help of vouchers or tax credits) private schools—the regular public schools lose children and money, and thus jobs. From a societal standpoint, this is not a problem at all. There would simply be more kids getting educated in charters and private schools, and the money and jobs would follow the kids. As they should. The regular public schools would lose money and jobs, but they would also have fewer kids to educate. Yet this kind of sensible shift is the last thing the unions want to see happen — because the regular public schools are unionized, and charters and private schools (with rare exceptions) are not. When families are given the right to choose, unionized teachers lose jobs and nonunion teachers gain them. So choice, while not threatening to teachers per se, is threatening to union members — and the unions are dedicated to protecting those jobs. To make matters worse, were choice adopted on a grand scale, it would also threaten the unions' very survival: for if families actually had lots of attractive options to choose from, the unions could well suffer a devastating plunge in membership, resources, and power. This is their greatest fear … [P]ublic opinion polls consistently show[] (then and now) that its greatest supporters are poor and minority parents … Ironically, the first person to bring charters to public attention was AFT President Al Shanker, in a 1988 speech before the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. Building on the work of educator Ray Budde, who had called for “chartering” as a means of freeing teachers to initiate new programs within their schools, Shanker extended the idea to the chartering of schools themselves, arguing that the creative potential of teachers, long stifled by bureaucracy, should be unleashed to drive education reform and improve education. He proposed that innovative teachers be granted charters by local districts to set up their own schools and that they be given the autonomy to do things differently and go their own ways. Parents, meantime, would be allowed to choose whether to send their kids to one of these new types of public schools and would thereby be provided with a system of public school choice that would substitute for, and indeed render unnecessary, vouchers for private schools. Shanker's vision of freeing schools and teachers to be innovative, however, was really a vision of freeing them from district control. They were not to be freed from union control. Quite the contrary, Shanker's charter schools would be run by teachers, who in turn would be unionized and covered by collective bargaining contracts, making the schools subject to the power and control of local unions. By offering his dramatic proposal for charter schools, then, Shanker was “embracing” choice and innovation—but in a distinctive, highly selective way that reflected his interests as a union president … Reformers quickly picked up on the charter idea, but not on Shanker's version of it. Their emphasis was on true autonomy—from district control, from local and state regulations, and from union power and collective bargaining contracts … The fact is, although charters are a relatively easy sell to most Republicans, they also have a special appeal to Democrats, and this appeal has been politically crucial to the movement as a whole, giving charters much broader support across the political spectrum — and brighter political prospects — than vouchers. Democrats have good political reason to support some form of meaningful school choice for their constituents. They are well aware that disadvantaged children are often stuck in terrible schools, and they do not want to be in the position of denying them desperately needed opportunities. Nor do they relish standing in the way of parents when they want to make choices for their kids. So charters offer Democrats an attractive middle ground: they can support more public sector choice for disadvantaged families (and other families too), and at the same time, they can appease the unions by opposing vouchers and going along with some of the restrictions the unions want to see imposed on charters. As a result, the choice movement has found it easier to pick up (some) Democratic allies in pushing for charter schools, and easier to win on that dimension of choice — although what they win is usually weak, because it is larded up with union-backed restrictions … But now that most states have charter laws and now that charters are so popular, the unions have often followed a more accommodationist strategy: they express their “support” for charter schools in concept—and then “collaborate” with policymakers in the legislative process to ensure that any new bills are filled with restrictions that neuter the reforms.Among the usual restrictions: stunningly low ceilings on the number of charters allowed statewide, lower per-pupil funding than the regular public schools, districts as the sole chartering authorities (because the districts don't want competition and have incentives to refuse), no charter access to district buildings, no seed money to fund initial organization, requirements that charters be covered by union contracts, and, in general, the imposition of as many of the usual state and district regulations as possible, to make charters just like the regular public schools. The unions don't always get every restriction they want, especially with regard to collective bargaining. Restrictive charter bills are nonetheless the norm—and as a result, almost all charter systems have been designed, quite purposely, to provide families with very little choice and the public schools with very little competition.

(In my own state of Virginia, state law strictly limits charter school operations. In Virginia, school boards must authorize charter schools and charters can only enroll students living in the district’s attendance zone. State law also does not offer charter schools much flexibility from traditional school requirements, and so only about half a dozen charter schools are open in Virginia.)

As Moe writes:

[T]he road to progress for charter schools has been a rocky one indeed. After two full decades of reform and despite all the accolades heaped upon them by prominent public officials from President Obama on down, the charter movement has managed to generate a mere 5,000 schools or so (as of 2009-10): a pittance compared to the more than 90,000 regular public schools that populate the larger system. They enroll just 3.4 percent of the nation's public school students (1.7 million students out of some 50 million). The tiny enrollments, however, are no indication of what families want for their children. Most of the existing charters have long waiting lists of children eager to get in. In Harlem, for instance, charter schools are enormously popular, enrolling 20 percent of public school kids, but many more are clamoring to get in and can't, because there aren't nearly enough charters to take them. In the spring of 2010, some 14,000 Harlem children submitted applications for just 2,700 open slots, and more than 11,000 were turned away. Nationwide, about 420,000 children are on wait lists, hoping to get into schools that don't have room to take them. The demand for charters far outstrips the supply. In New Orleans, where the traditional school system was destroyed by Katrina and reformers gained the upper hand, charters now enroll a stunning 61 percent of students. This is obviously an unusual situation.

Teacher union influence in opposing charter schools continues during the current presidential administration. As Howard writes:

No political leader is immune from union influence. The flip-flop of President Joe Biden on charter schools is a case in point. The charter school movement got a huge boost by the Race to the Top program initiated by the Obama-Biden administration. As Jonathan Chait recounts, In the dozen years since Barack Obama undertook the most dramatic education reform in half a century—prodding local governments to measure how they serve their poorest students and to create alternatives, especially charter schools … the evidence for their success has become overwhelming. But on the campaign trail in 2020, as Chait reports, Joe Biden reversed course: “I am not a charter-school fan because it takes away the options available and money for public schools.” [My note: actually, charter schools are publicly-funded schools, they just aren’t subject to union rules.] In March 2022, President Biden proposed new regulations that give teachers unions legal knives to kill charters—requiring that charters serve a “diverse population” (instead of the overwhelmingly minority populations), require proof of “unmet demand” because of “over-enrollment of existing public schools” (instead of demand prompted by poor public school quality), and require that the charter collaborate with a “traditional public school” and provide a letter from the public school affirming this partnership — in effect, giving public schools a veto.

Teachers unions like the American Federation of Teachers are so opposed to education reforms that they previously opposed even many elements of Democratic President Obama’s education reform agenda. As reported in the New York Times magazine:

[AFT President] Weingarten embarked on a cross-country bus tour to get out the vote for Joe Biden. His Democratic predecessor, Barack Obama, had not always been in sync with the A.F.T.; the union opposed elements of Obama’s Race to the Top program, which sent money to states that reformed their public-education systems by, among other things, weakening teacher tenure, introducing data-driven accountability measures and adding more nonunionized charter schools. Biden, by contrast, vowed to focus on neighborhood public schools rather than charters and criticized the standardized-testing regimes and teacher evaluations that were a hallmark of Race to the Top.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll examine teacher pay, work schedules, and absences.

Paul, This stuff should be manifesto level for every right-thinking politician and every right-thinking American. I am astounded every time I read another piece by you not only about how bad things are, but even more by how inadequate/opaque any responses from the political classes are. Truth is truth -- ignoring it does not make it go away. Depressing, really. Where are the truth tellers? (Other than you, obviously...)