As we continue this essay series on the influence teachers unions have on the American public education system, this essay will examine a fundamental imbalance in that system, namely the situation in which teachers unions (in states that allow collective bargaining, and to a lesser extent in other states) have a guaranteed “seat at the table” under U.S. law, whereas parents and students don’t, and have to fend for themselves in politics without an insider’s advantages.

In his book How Policies Make Interest Groups: Governments, Unions, and American Education, Michael Hartney summarizes how the Supreme Court has read U.S. labor law to allow teachers unions to “assume an official position in the operational structure” of public schools. As Hartney explains:

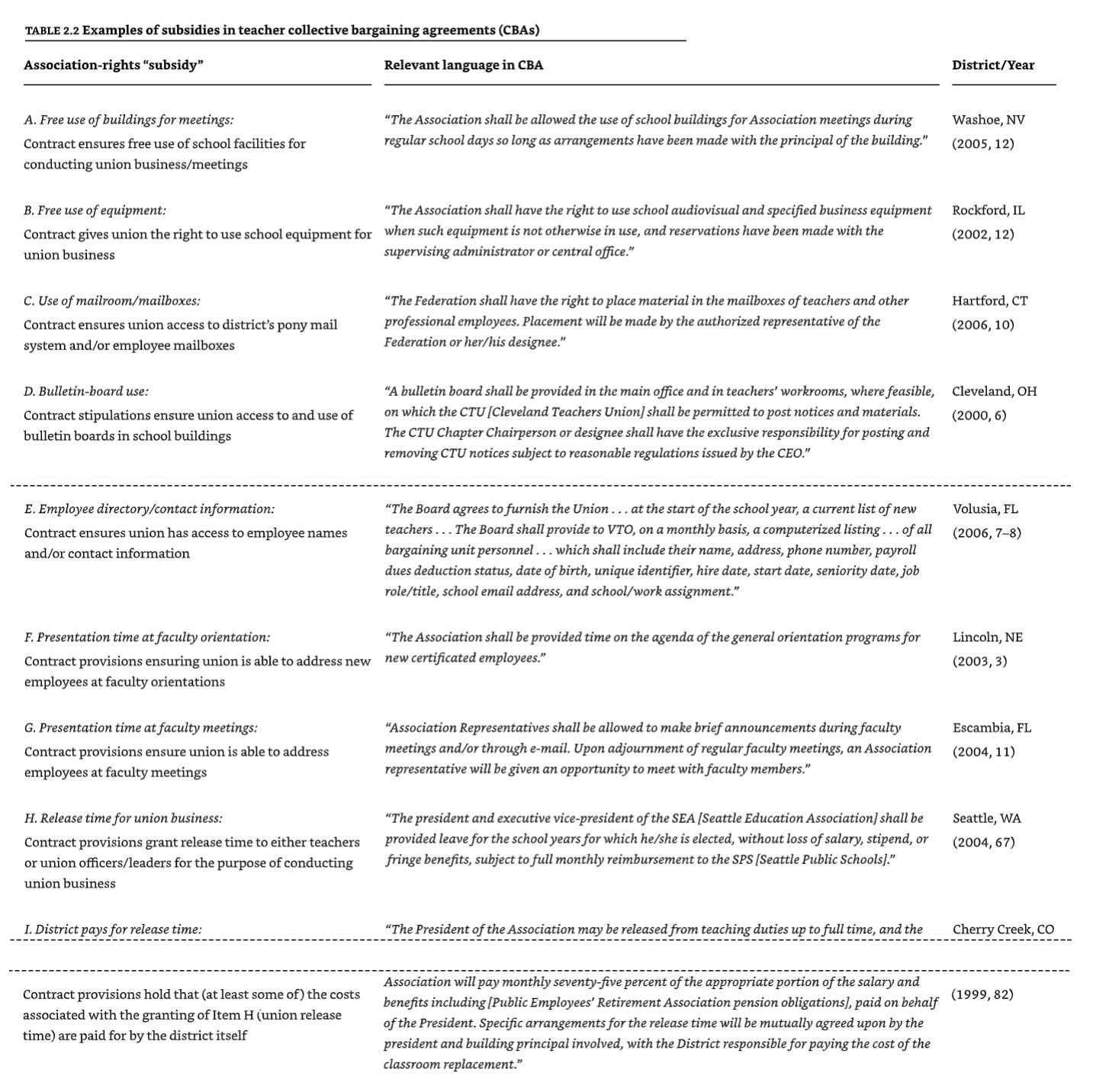

A lesser known, though equally important, [Supreme Court] decision in this line of cases was the justices’ 5–4 decision in Perry Education Association (PEA) v. Perry Local Educators’ Association (PLEA). In Perry, the Supreme Court settled a 2–1 split that had divided the federal circuit courts over the question of whether school districts could grant a single union the exclusive right to use public resources like the school district’s internal mail system. In affirming the right of school districts to subsidize a single union, the court lifted the curtain and exposed just how much public-sector bargaining had changed the education landscape: “The [district’s mail] system was properly opened to PEA [the union], when it, pursuant to [Indiana labor law] was designated the collective bargaining agent for all teachers in the Perry schools. [The union] thereby assumed an official position in the operational structure of the District’s schools, and obtained a status that carried with it rights and obligations that no other labor organization could share.” Perry is important because it reveals how public-sector labor law “institutionalizes” private teacher-union interest groups as formal public actors in American education. Enabling teachers unions to “assume an official position in the operational structure” of school-district governments significantly influences the balance of power in education politics. Whereas the fortunes of most interest groups tend to ebb and flow in response to shifts in the broader political winds, public-sector labor law virtually assures that teacher interests will have a permanent seat at the policymaking table. As Sarah Anzia observes, “in districts with mandatory collective bargaining, teacher unions automatically get a place at the table: District officials are required to negotiate and reach agreement with teacher unions on salaries, benefits, and work rules.” Political scientists have long recognized that political influence is predicated on access. Regardless of whether we characterize such access as gaining entree to a policy monopoly, an iron triangle, or an issue network, what’s clear is that interest groups will be more influential when they have access to the policymaking venues that have authority over the issues they care about. For education interests, those institutions are clearly state and school-district governments. The revolution in public-sector collective bargaining that occurred in the late 1960s and 1970s ensured that teachers unions would have a permanent reservation at those tables. There is also profound irony in the precedent that was established by the Supreme Court in Perry. In pushing back on the dissenting justices’ position that the school district’s mail system should have been treated as a public forum that was accessible to other advocacy groups, the majority argued that if Indiana’s labor law did not allow local school districts to confer subsidies solely to the exclusive representative teachers union, the law would implicitly require that districts grant those same rights to “any other citizen’s group or community organization with a message for school personnel—[from] the Chamber of Commerce, right-to-work groups, or any other labor union ...” … [T]he Perry case underscores how public-sector bargaining uniquely advantages teachers unions as political advocacy organizations. This advantage is especially evident when one compares the organizing challenges facing teachers with the much steeper hurdles faced by other education stakeholders. When most other education stakeholders attempt to overcome their collective action challenges by building the requisite organizational infrastructure to mobilize their constituents in education politics, they do so without the same benefit of having been designated an official actor in school governance.

Hartney then compared the situation of teachers unions to that of parents:

Parents offer an especially interesting case for comparison. A number of observers have drawn attention to recent efforts to organize and mobilize parents in education politics. An illustration of the numerous challenges that parent activists face is depicted in the 2012 Hollywood film Won’t Back Down (starring Maggie Gyllenhaal and Viola Davis). Loosely based on real-world events related to California’s “parent trigger law,” Gyllenhaal plays a low-income single mother who is trying to mobilize parents to pressure the school board into converting her child’s chronically low-performing school into a charter school. Setting aside the happy (and unrealistic) Hollywood ending, the film shows Gyllenhaal struggling to recruit and mobilize parents to support her cause because she lacks the exact sort of resources that collective bargaining made available to teachers unions. For example, she has to take unpaid leave from her job to engage in door-to-door canvasing. Without contact information for all the parents in her child’s school, she has a difficult time tracking them down and getting signatures. Likewise, there is no cheap and easy way for her to contact and communicate reliably with parents (no district-provided parent mailboxes or email listservs). Before she can make any progress, Gyllenhaal discovers that the teachers union has counter-mobilized the district’s employees against her cause … Many different groups of citizens have a vested interest in the public schools. But unlike teachers unions, these other stakeholders cannot count on a formal set of government policies to strengthen their organization and political-mobilization efforts. Likewise, their interests in education are not formally recognized with an official seat at the policymaking table.

Hartney describes how collective bargaining helps teachers unions politically in two crucial ways:

Collective bargaining promoted the teachers unions’ political power in two basic ways. First, because exclusive recognition meant that teachers unions would represent all of the teachers in a school district (both union members and nonmembers alike), many states adopted laws that provided unions with security provisions to discourage free riding and ensure that unions had sufficient financial resources to bargain. In public-sector labor relations, union-security provisions take three basic forms. First, under “dues checkoff” arrangements, the school district agrees to deduct union dues and fees from each teacher’s paycheck, giving the union greater financial security. Second, “maintenance of membership” clauses require that members remain in the union for the duration of the bargaining agreement, providing certainty and stability to the union. Finally, prior to the Supreme Court’s recent Janus decision, unions could negotiate “agency shop” provisions, requiring nonmembers to pay fees to the union to help cover the union’s costs of representing them … [T]hese security provisions played an important role outside the collective bargaining process. They provided newly emerging teacher-union interest groups organizational subsidies that enabled them to more easily recruit members, raise revenue, and ensure long-term group maintenance and survival.

Public school reforms have been stymied largely because the political apparatus advantage the law gives teachers unions was already in place by the time it became obvious there was a need for public school reforms. As Hartney writes:

By the early 1990s, just a few years after A Nation at Risk sparked the rise of the modern education- reform movement, the NEA and its affiliates were already a billion- dollar interest group. The New York Times’ characterization of the NEA’s tepid response to this new reform environment read like a textbook political- science lesson on vested interests. As the 1980s came to a close, the Gray Lady observed that the NEA remained “solidly against proposals for major changes that [were] gathering increasing support from parents and politicians … [including] merit pay for teachers and expanding parental and student choice.” … The simple fact that teachers got politically organized well before education reform made it onto the nation’s agenda put teachers unions in a far stronger position than reform groups. Whereas reform groups would need to overcome union power and win at each stage of the policymaking process, teachers unions only needed to play defense. They could preserve their power and influence in education politics and policy simply by blocking, diluting, or weakening the implementation of the reform movement’s agenda … At the subnational level, teachers unions face less direct political competition; they also benefit from multiple veto points that allow them to block or influence reforms that require coordinated implementation from the state to the local level. Finally, and most importantly, they have the advantage of holding, as the Supreme Court’s Perry majority put it, “an official position in the operational structure” of school-district governments.

As Terry Moe writes in his book Special Interest: Teachers Unions and America’s Public Schools:

In addition to all this, the teachers unions are fabulously wealthy. Do the math. If some 4.5 million members are paying about $600 per person per year in dues, the total comes to $2.7 billion annually. And that's just their dues money. The unions don't spend all of it on politics, of course, but their capacity for converting money into power is way beyond what almost all interest groups can even dream of … By any reasonable accounting, the nation's two teachers unions, the NEA [National Education Association union] and the AFT [American Federation of Teachers union], are by far the most powerful groups in the American politics of education. No other groups are even in the same ballpark. Consider what they've got going for them. They have well over 4 million members. They have astounding sums of money coming in regularly, every year, for campaign contributions and lobbying. They have armies of well-educated activists manning the trenches in every political district in the country. They can orchestrate well-financed public relations and media campaigns anytime they want, on any topic or candidate. And they have supremely well-developed organizational apparatuses that blanket the entire country, allowing them to coordinate all these resources toward their political ends.

As Hartley observes, teachers enjoy a wide variety of political organizational “subsidies” that make it much easier for union members to organize politically:

As Hartley writes, “Though federal law expressly prohibits labor unions from using their general treasury funds to donate to federal candidates or parties, teachers unions are free to spend their dues revenue on PAC administration and solicitation, lobbying, independent expenditures, ballot initiative or referenda campaigns, rallies, protests, and member communication and voter mobilization drives. More importantly, many state governments set no limits whatsoever on the use of union dues money in subnational politics.”

As Moe writes:

No other group in the politics of education— representing administrators, say, or school boards or disadvantaged kids or parents or taxpayers— even comes close to having such weaponry. For perspective, though, it is important to add that the teachers unions are among the most powerful interest groups of any type in any area of public policy. Yes, the bankers have lots of money. Yes, the trial lawyers do too. And so do the National Association of Realtors, the Chamber of Commerce, and lots of other groups. But which groups— of all special interest groups of all types— were the nation's top contributors to federal elections from 1989 through 2009? Answer: the teachers unions.

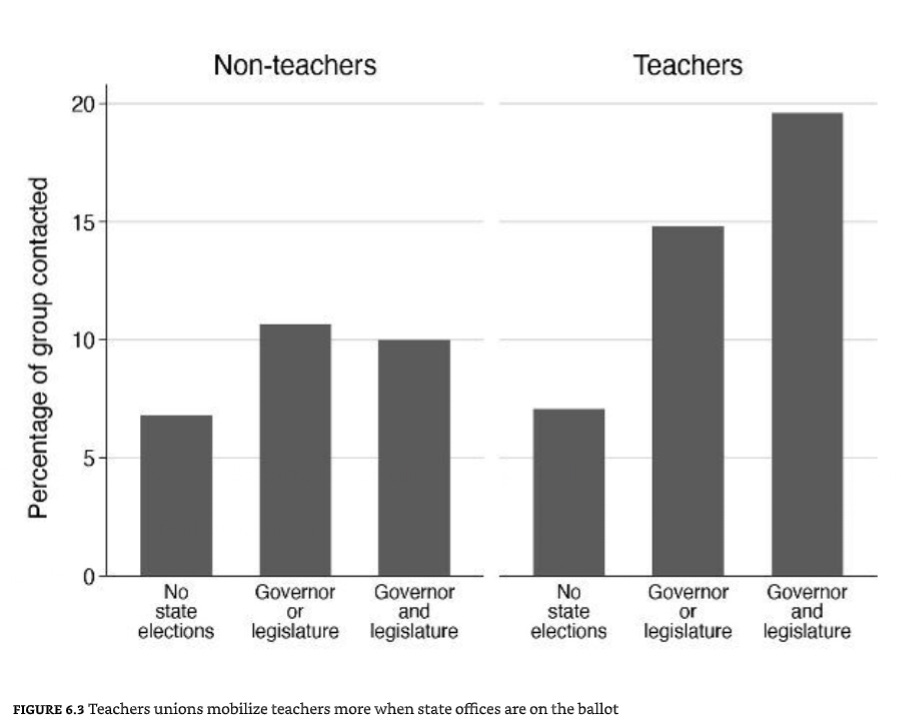

And with those organizational subsidies comes greater political participation. As Hartley writes:

The average teacher, for example, undertakes one political act when state elections are on the ballot compared to just 0.63 acts in elections where only federal offices are at stake. The results [of the study] confirm that union mobilization is indeed very likely behind the higher rates of teacher participation in state politics. As figure 6.3 shows, teachers are much more likely to report being contacted to participate by a nonparty group—presumably their own union—when governors and state legislators are running for office.

Hartley also writes that

Three studies—each from a different decade—reveal that teachers unions hold a consistent advantage over other education interests in state political giving. In one early study, Eugenia Toma and colleagues examined the proportion of PAC dollars contributed by teacher-unions state affiliates compared to all contributions from state education interests during the 1990s. She found that, on average, teachers unions accounted for more than 90 percent of all PAC contributions made by education-advocacy groups in the states. A decade later, Terry Moe’s analysis of teacher-union PAC giving confirmed that the 1990s were no fluke. Looking at two election cycles in the late aughts, Moe compared teachers unions’ contributions in state politics with the contributions of all other interest groups. In most states, he found that teachers unions were ranked first or among the top handful of contributors. Even when Moe compared teachers unions to business interests, the unions came out on top in most states … [T]eachers unions maintained their longstanding advantage in state political giving. Political scientists Sarah Reckhow and Leslie Finger examined how much various education groups contributed to state politics before (2000–2003) and after the Great Recession (2014–2017). Even in an era of labor retrenchment, they calculated that teachers unions accounted for 92 percent of all the contributions made by education-advocacy groups in state politics between 2014 and 2017 …

As the Wall Street Journal reported in December, 2023:

The alliance between Democrats and public unions is a dominant feature of modern politics, and the mutual love is growing. That’s the message of a new report by the Commonwealth Foundation, which dug into how government unions fund politics through direct campaign spending and political action committees. The four largest government unions are the National Education Association (NEA), American Federation of Teachers (AFT), Service Employees International Union (SEIU) and the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (Afscme). In the 2021-2022 election cycle, they spent more than $708 million combined on politics. Since 2012 union spending on federal elections has nearly tripled. Democrats and their causes receive 95.7% of the cash from unions’ political action committees.

These huge legal and institutional advantages of teachers unions allow them to block just about any reforms that threaten their preferred policies. As Hartley writes:

With the second face of power [which involves controlling the parameters of a discussion], vested interests are powerful because they can keep issues off the government’s agenda altogether … In rare instances, scholars find clever ways to observe the second face of power. Terry Moe, for example, used a natural experiment—Hurricane Katrina—to observe how elected officials responded when they were given the opportunity to redesign the New Orleans public school system free from the power of vested-interest opposition. Even in a traditionally “weak” union state like Louisiana, Moe deduced that teachers unions had used the second face of power to keep radical education reforms off the agenda in New Orleans prior to Katrina. After the storm and unburdened by union power, the same policymakers who had shown no interest in radical reform suddenly became cage-busting school reformers.

But without the institutional change that can follow a natural disaster, Moe writes:

The teachers unions are the raw power behind the politics of blocking. The Democrats do the blocking. Some of my Democratic readers may not like to hear such a thing, and may suspect that I am a Republican with an ax to grind. But I am not a Republican, and I have no stake in trashing the Democrats. My aim here is to understand the role of the teachers unions in American education and simply to tell it like it is.

As Philip Howard writes in his book Not Accountable: Rethinking the Constitutionality of Public Employee Unions:

Teachers unions prevent public schools from working, and they also prevent any solutions … Michael Lilley of the American Enterprise Institute and Sunlight Policy Center unpeels the onion of teachers union activities in New Jersey and calculates that, from 2013 to 2017, $65 million per year, or “58 percent of total operational expenditures,” was devoted to political activity. But even Lilley’s estimate of actual spending is low, because it does not allocate any portion of massive union overhead to political activities … Some unions have gone one step further and gotten their own members elected. In many states, teachers unions dominate school board elections, off-year events with low turnout where union members often run … The correlation of union support and election success, Michael Hartney and others have found, is extremely high: 70 percent of union-endorsed school board candidates win. What public unions ask in return is the rejection of most reforms, plus continual incremental controls and benefits. Public unions do not get everything they want, at least not immediately, but there is little organized opposition, and the steady drumbeat of pressure is only in one direction … While over 90 percent of union support goes to Democrats, even for Republicans it’s better just to steer clear of the dragon guarding the cave of public administration … New York City mayor Mike Bloomberg and his school chancellor Joel Klein decided to pilot a new program where the decision to grant tenure to new teachers would be determined in part by the test scores of their students. The union strongly opposed this but had no legal basis to reject it. “In an awesome display of raw political power,” Terry Moe reports, the union “went to the state legislature in the spring of 2008 and got it to pass a law prohibiting any district, anywhere in the state, from using test score data as even one part of the tenure evaluation process.” … In 2007 Washington, DC, mayor Adrian Fenty brought in Michelle Rhee as schools chancellor. Rhee closed schools that were failing, fired several hundred teachers and principals—and instituted merit pay. The teachers unions fought her at every step, but her reforms seemed to be working and the unions were unable to halt her progress. So the unions went to plan B and “put the hard sell on” a council member to challenge Mayor Fenty in the Democratic primary. The American Federation of Teachers reportedly spent around $1 million to unseat Fenty. Fenty lost, and Rhee resigned.

And even though the federal No Child Left Behind Act was enacted into law in 2002, with the support of Democratic Senator Edward Kennedy, teachers unions blocked many of the reforms it could have contained. As Moe writes:

[E]ven in a losing cause, [the teachers unions] did not entirely lose out. Indeed, they scored important victories— notably, in stipulating that nothing in NCLB's requirements would take priority over the provisions written into local collective bargaining contracts, in eliminating private school vouchers as a means of providing options for kids in failing public schools, and in eviscerating the apparent NCLB requirement that veteran teachers need to demonstrate competence in their subject matters (an evisceration that led, years hence, to the charade of virtually every one of the nation's 3 million teachers being declared “highly qualified”). Perhaps most important of all, they used their power to ensure that NCLB was almost devoid of serious consequences when districts and schools failed to do their jobs. As education journalist Joe Williams (now executive director of Democrats for Education Reform) rightly observed as the realities on the ground were becoming clear, “Improve your schools, or someone else will. That was supposed to be the bite in the federal No Child Left Behind Act that would leave teeth marks on underperforming school districts, ushering in long- resisted reforms and restructuring in the education systems where they were most needed … But nearly five years after No Child Left Behind was signed into law, not a single school district has undergone radical restructuring … as part of corrective actions for districts under the law. To date, NCLB has been relatively toothless in terms of holding districts accountable through the use of strong- arm sanctions …” Underperforming districts have encountered little pain under NCLB other than the stigma that comes from being branded failing systems.

And while Hurricane Katrina may have liberated Louisiana schools, the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the blocking power of teachers unions in the face of increasingly mounting evidence that prolonged school closures were an unecessary disaster for students. As Hartley writes:

One need look no further than the COVID-19 pandemic to see that localism remains a powerful and enduring force in the United States. Even as mounting scientific evidence showed that schools could be reopened safely, two US presidents and numerous governors found they had little practical power to reopen schools when local school boards struggled to obtain cooperation from teachers unions. While more-centralized education systems in other parts of the world reopened far more quickly, the inability of school boards to ink reopening agreements with their teachers unions played no small role in keeping half of all students out of school for a full year.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll examine teachers unions’ opposition to charter schools and school choice programs.