In the last essay we looked at how Charles Murray gave people a sense of the scope of change over the past 10,000 years. Professor David Christian, in his excellent Great Courses lecture series on “Big History: The Big Bang, Life on Earth, and the Rise of Humanity,” brings us even further back, further enlarging our context for this place and time in the universe:

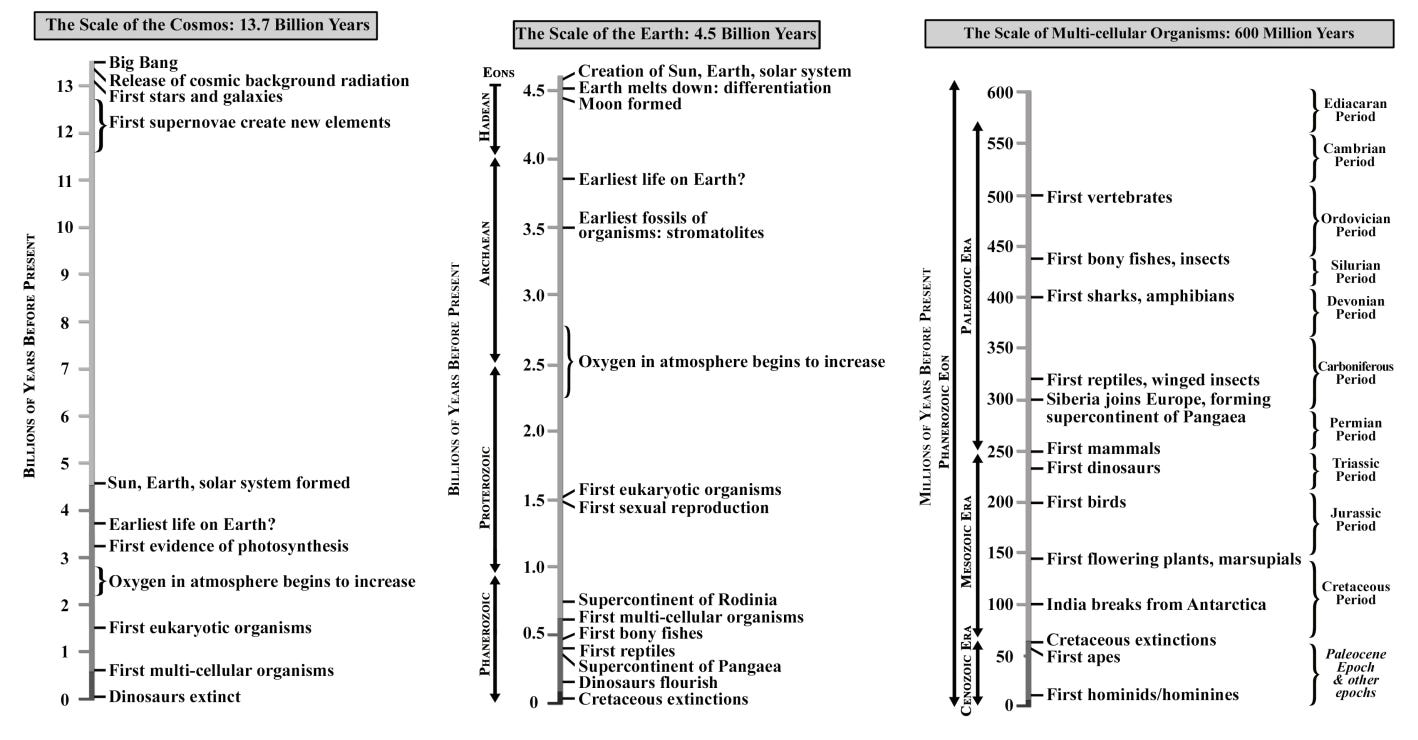

We can grasp [our modern time scale, with a Universe just over 13 billion years old] more easily if we shrink it one billion times, so that the whole history of the Universe can fit into just 13 years. On this scale, our Earth would have been formed about 5 years ago. The first multi-celled organisms would have evolved about 7 months ago. After flourishing for several weeks, the dinosaurs would have been wiped out by an asteroid impact about three weeks ago. The first hominines would have appeared about three days ago, and our own species just 53 minutes ago. The first agriculturalists would have flourished about 5 minutes ago, and the first Agrarian civilizations would have appeared just 3 minutes ago. Modern industrial societies would have existed for just six seconds.

What were the highlights of those “three days ago” out of thirteen years?

Agriculture appeared about 10,000 or 11,000 years ago. Before the appearance of agriculture [for hundreds of thousands of years], all human beings were foragers. If asked (perhaps around a campfire) to explain how everything got to be the way it is, how might we respond? Let’s begin with human history. We live in the largest and most complex human community ever created. Six billion humans, often in conflict with each other, are linked through trade, travel, and modern forms of communications into a single global community. This community was created in just a few hundred years. About 300 years ago, human beings crossed a sort of threshold as human societies became more interconnected and began to innovate faster than ever before. For 5,000 years before this, most people had lived in the large, powerful communities we call “Agrarian civilizations.” They had cities with magnificent architecture and powerful rulers sustained by large populations of peasants who produced most of society’s resources. Innovation was slower, so history moved more slowly, and there were fewer people than today. Two thousand years ago, there were about 250 million people on Earth. The first Agrarian civilizations appeared in regions such as Mesopotamia, Egypt, and China. During the previous 5,000 years, humans had increasingly lived in small peasant villages governed by local chiefs. Yet many still lived by foraging, gathering what they needed as they migrated through their home territories. The appearance of agriculture, just over 10,000 years ago, counts as a fundamental historical threshold because agriculture increased the amount of resources humans could extract from a given area. By doing so, it stimulated population growth and innovation and laid the foundations for the first Agrarian civilizations. In the preceding 200,000 to 300,000 years, all humans had lived as foragers, in nomadic, family-sized communities. Slowly, they spread through Africa and around the world. For most of this time, humans were only slightly more numerous than our close relatives, the great apes, are today. Our species, Homo sapiens, appeared about 200,000 to 300,000 years ago somewhere in Africa. What made them different from all other animals, and enabled them to explore so many different environments, was their remarkable ability to exchange and store information about their environments. Humans could talk to each other, they could tell stories, and unlike any other animals, they could ask about the meaning of existence! Their appearance counts as a fundamental threshold in our story.

And what of the time scale before humans evolved?

To understand how the first humans appeared, we must survey the history of life on Earth. Like all other species, our ancestors evolved by natural selection. They evolved from intelligent, bipedal, ape-like ancestors known as “hominines” that had appeared about 6 million years earlier. The hominines were descended from primates: tree-dwelling mammals with large brains and dexterous hands that had first appeared about 65 million years ago. The mammals were furry, warm-blooded animals that had first evolved about 250 million years ago. They were descended from large creatures with backbones, whose ancestors had left the seas to live on the land about 400 million years ago. These were descended from the first multi-celled organisms, which appeared about 600 million years ago in the Cambrian era. During the preceding 3 billion years, all living organisms on Earth were single-celled. The first living organisms had appeared by about 3.8 billion years ago, just 700 million years after the formation of our Earth. They were the ancestors of all living creatures on today’s Earth … The appearance of life is one of the most important thresholds in the big history story.

And what of the time scale before any life came to be?

Life could evolve only after the crossing of three earlier thresholds: the creation of planets, stars, and chemical elements.

Our Earth was formed about 4.5 billion years ago, along with all the other planets, moons, and asteroids and comets of our solar system, from the debris formed as our Sun was created. Solar systems probably formed countless billions of times in the history of the Universe.

Our planet, like the living organisms that inhabit it, is made up of many different chemical elements, so neither could have formed if the chemical elements had not been manufactured in the violent death throes of large stars (in supernovae) or in the last dying days of other stars. The earliest stars may have died within a billion years of the creation of the Universe. Since then, billions upon billions of stars have died and scattered new elements into interstellar space. The first stars were born, like our Sun, from collapsing clouds of gas within about 200 million years of the big bang. Today, there may be more stars than there are grains of sand on all the beaches and deserts of our Earth.

And what of the very, very beginning of it all?

Our Universe began as a tiny, hot, expanding ball of something popped out of nothingness like an explosion about 13.7 billion years ago. The explosion has continued ever since, and we are part of the debris it has created.

Despite the limitations of any account of big history, the story is one we need to know and tell. Telling it backward is a good way of showing how such stories can help us map ourselves onto the cosmos. We see how the modern world fits into the larger story of human history, how human history fits into the history of life on Earth, and how these stories fit into the largest story of all—that of the Universe as a whole. Like the different parts of a Russian matryoshka doll, each story is nested in and helps explain the stories surrounding it.

With all this as our background, it will be much easier to appreciate how the times we live in today are the most rapidly-changing in all of human history. That will be the subject of the next and final essay in this series.

You actually believe that?