In previous essay series, we’re explored free speech and the Socratic method. Over the last couple years, the federal government has taken some disturbing actions against free speech and debate. Some of those actions include the following.

As Peter Walliston writes:

In a recent interview on Joe Rogan’s show, Michael Shellenberger described his and his colleagues’ awakening to the pervasive government effort to stamp out unwanted ideas and opinions on Twitter. He, Matt Taibbi, and Bari Weiss—all independent journalists—were given access by Elon Musk to review Twitter’s files for, among other things, the reasoning behind Twitter’s clamp-down on news about such matters as COVID masking and the Hunter Biden laptop. “Over time,” Shellenberger said, “we kept finding weird stuff. … We found that a lot of people [then employed at Twitter] used to work at the FBI. The CIA shows up in the Twitter files. The Department of Homeland Security. We’re like, ‘What the hell is going on?’” “The story quickly shifted from what we, and I think Elon, thought, which was that it was just very progressive people being biased in their content moderation, in their censoring, to ‘There is a huge operation by US government officials, US government contractors … basically demanding that Twitter start censoring people.’ At that moment, the story shifted for all of us.” … [A]t roughly the same time that Shellenberger and others were shocked by what they found in Twitter’s files, a Federal District Court in Louisiana was considering whether to go to trial with a case in which the plaintiffs were alleging that the direct involvement of government agencies and employees with Twitter was a violation of the First Amendment. In Missouri v. Biden, et al, the plaintiffs—including the states of Missouri and Louisiana and many private individuals whose views had been censored by Twitter—claimed that the pressure brought on Twitter by government agencies and government employees should be considered government action that deprived them of their free speech rights. Missouri and Louisiana, in turn, argued that the suppression of dissenting views by Twitter interfered with their ability to “follow, measure, and understand the nature and degree of [their constituents’] concerns,” among other impairments. There were 67 defendants in this case, including President Biden, the Census Bureau, the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the National Institute of Allergy & Infectious Diseases, and the Departments of Commerce, Health & Human Services, Homeland Security, Justice, State, and Treasury. They also include some individuals with familiar names: Anthony Fauci, Karine Jean-Pierre, Alejandro Mayorkas, and Jennifer Psaki, to name a few. After an extensive preliminary hearing on the defendant’s motion to dismiss, Judge Terry A. Doughty, a Federal District Judge in the Western District of Louisiana, denied the motion to dismiss and ordered the case to be tried. Under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, “No provider or user of an interactive computer service [like Twitter] is held liable on account of ... any action voluntarily taken in good faith to restrict access to or availability of material that the provider considers to be ... objectionable, whether or not such material is constitutionally protected.” In other words, Section 230 was intended to relieve Twitter and other social medium firms of liability for censoring material the firm deems objectionable. This broad language could, and does, include opinions of all kinds. However, the plaintiffs alleged that their opinions and other communications had been censored by Twitter under pressure from elected individuals and employees of government agencies which, they argued, was a violation of the First Amendment’s guarantee of free speech. In making its decision to proceed to a trial, the court noted that Twitter had been operating under direct threats from powerful individuals that Twitter’s statutory exemptions under Section 230 might be removed if it did not clamp down on what was considered “misinformation.” President Biden, then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, Vice President Kamala Harris, and Senator Richard Blumenthal were all cited as having made such statements. What makes this case important and potentially consequential is that it concerns insistent demands on the part of government for the suppression of certain views, combined with the ability to modify or eliminate the benefits conferred by Section 230 … Plaintiffs further allege,” said the court, “that, aware of the importance of this immunity to social-media companies, the Biden Administration and his political allies ‘have a long history of threatening to use official government authority to impose adverse legal consequences against social-media companies if such companies do not increase censorship of speakers and messages disfavored by Biden and his political allies … What makes this case important and potentially consequential is that it concerns insistent demands on the part of the government for the suppression of certain views, combined with the ability to modify or eliminate the benefits conferred by Section 230. This combination put the administration in a position that a non-governmental organization would not normally be able to attain and made its desires and interests into credible threats. It is possible to conceive of a government agency putting its ideas before Twitter or any other social media company without an implied threat, but the court seems to hold that in this case, the government crossed the line.

Government officials’ use of informal pressure — bullying, threatening, and cajoling — to sway the decisions of private platforms and limit the publication of disfavored speech, has come to be called legal “jawboning,” and it’s become so common that it’s the subject of an extended analysis by the CATO Institute, which can be found here.

As Jay Bhattacharya writes at the Free Press:

On Friday [September 8, 2023], at long last, the Fifth Circuit Court ruled that we were not imagining it—that the Biden administration did indeed strong-arm social media companies into doing its bidding. The court found that the Biden White House, the CDC, the U.S. Surgeon General’s office, and the FBI “engaged in a years-long pressure campaign [on social media outlets] designed to ensure that the censorship aligned with the government’s preferred viewpoints.” … ... a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit unanimously restored a modified version of the preliminary injunction, telling the government to stop using social media companies to do its censorship dirty work: “Defendants, and their employees and agents, shall take no actions, formal or informal, directly or indirectly, to coerce or significantly encourage social-media companies to remove, delete, suppress, or reduce, including through altering their algorithms, posted social-media content containing protected free speech. That includes, but is not limited to, compelling the platforms to act, such as by intimating that some form of punishment will follow a failure to comply with any request, or supervising, directing, or otherwise meaningfully controlling the social media companies’ decision-making processes.”

Even statements that ought to be considered patently obvious to the most casual observer have become the subject of prosecution by federal government agencies. As John Berlau and Stone Washington write in the Wall Street Journal:

In a lawsuit against Townstone Financial, a small Chicago-area nonbank mortgage firm, the CFPB [Consumer Financial Protection Bureau] is signaling that it may attempt to punish anyone who complains about neighborhood crime. The CFPB accuses Townstone owner Barry Sturner and others affiliated with the company of making “statements that would discourage African-American prospective applicants from applying for mortgage loans.” The suit, filed in 2020, doesn’t provide any concrete examples of consumers that Townstone has allegedly mistreated. Rather, the CFPB points to a handful of statements Mr. Sturner and other company officials made over a four-year period on the Townstone Financial Show—a weekly radio program and podcast. These statements, according to the regulatory behemoth, discourage “prospective applicants, on the basis of race, from applying for credit.” The CFPB’s action against Townstone is concerning for many reasons. Chief among them is the lawsuit’s blatant attempt to apply antidiscrimination laws to speech made to a general audience in a mass-media venue rather than to individual customers or employees in a workplace. The Pacific Legal Foundation, a public-interest law group representing Townstone, warns in a legal brief that this approach to enforcement “would arrogate to the CFPB the authority to censor speech.” … In February [2023], federal Judge Franklin Valderrama in the Northern District of Illinois dismissed the CFPB’s suit, ruling that the law prohibits only discrimination against actual applicants, not discouragement of prospective applicants. Undaunted, the CFPB filed to appeal the decision on April 3. Among the statements highlighted in the lawsuit are Mr. Sturner’s descriptions of frequent weekend crime rampages on Chicago’s South Side as the work of “hoodlums” and his claim that police are keeping the city from “turning into a real war zone.” The CFPB also wags its finger at a host’s description of a Chicago suburb as an area in which “you drive very fast through” and “you don’t look at anybody or lock on anybody’s eyes.” The CFPB contends that these statements about majority-black communities would somehow “discourage prospective applicants living in majority- or high-African-American neighborhoods from applying for mortgage loans.” Yet the Townstone hosts’ candid comments about the crime epidemic in Chicago’s black neighborhoods are remarkably similar to recent statements of Mayor-elect Brandon Johnson … Under the CFPB’s interpretation of the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, anyone employed by or associated with a consumer finance firm who makes a random comment on social media could be subject to punishment by the agency. The same could even be true for a company employee who likes a tweet or forwards a post that the CFPB believes would “discourage” some unknown prospective applicant from applying for credit.

This tendency to suppress free speech results when people graduate from universities that fail to inculcate a respect for free inquiry and go on to work for the federal government. As Samuel Abrams writes:

The current source of protesting and cancel culture … is coming overwhelmingly from within the extremely liberal wing of the Democratic Party. This segment of the Democratic Party, albeit fairly small but with an outsized impact, is causing significant damage to our civic health by making it hard for many to question particular ideas and norms and disagree as so many Americans now live in fear of being protested or canceled by these aggressive mobs … In a 2022 survey from the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), 63% of liberal faculty said they can think of cases when it would be acceptable to shout down speakers, compared with 47% of moderates and 12% of conservatives. Nearly a third of liberal faculty (31%) believe that there are cases where blocking other students from attending a campus speech is acceptable, while just 16% of moderates and 5% of conservative faculty feel the same way. Professors have the duty to promote honest intellectual exploration and help students learn in environments that embrace free-ranging discourse. The faculty on the left are failing. Students mirror this ideological divide on campus. Another FIRE survey revealed that 75% of liberal students justify trying to prevent speakers from speaking on campus. This compares to 55% of moderates and 42% of conservative students. Almost two times the number of liberal students think that there are justifiable cases to silence speech compared to conservatives. A similar ratio emerges when asked about trying to block other students from attending a talk (31% of liberals compared to 15% of conservatives), as well as the legitimacy of using violence to stop the expression of ideas. The nation at large showcases almost identical ideological patterns. Data from the May 2021 American Perspectives Survey shows that about 15% of Americans have ended a relationship over politics. Forty-five percent of liberals, however, reported ending a friendship over politics. That compares to 22% of conservatives and only 11% of moderates.

The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (“FIRE”) reported on a survey from 2024 as follows:

FIRE conducted the largest survey ever on faculty free expression and academic freedom. The results are deeply disturbing. Almost one in four say their own departments are "somewhat" or "very" hostile to people with their political beliefs — and 23% worry about being fired over a misunderstanding. But it gets worse. Certain views are more targeted than others. Only 17% of liberal faculty say they hide their political views to keep their jobs, compared to a staggering 55% of conservative faculty. Additionally, only 20% said conservatives would even be welcome in their department. The threat of censorship is so pervasive on campuses across America that not even the cloak of anonymity is enough to put their minds at ease. While collecting our data, we were surprised to discover that some academics were afraid to take our survey for fear of being found out:

"The fact that I'm worried about even filling out polls where my opinions are anonymous is an indication that we, as institutions and as society, have lost the thread concerning ideas."

"I almost avoided filling out the survey for fear of losing my job somehow‚ [and I] waited about two weeks before getting the courage to take the risk in filling it out."

"I had already decided that this year will be the last one I teach at the university. For what I'm paid to teach the courses that I do, it's just not enough to outweigh the risk of potential public excoriation for wrong-think and its personal and professional impact on myself, my family, and my business."

The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression ranks colleges based on how tolerant they are of free speech, and its 2023 ranking found the following:

Harvard University obtained the lowest score possible, 0.00, and is the only school with an “Abysmal” speech climate rating. The University of Pennsylvania, the University of South Carolina, Georgetown University, and Fordham University also ranked in the bottom five. The key factors differentiating high-performing schools (the top five) from poorly performing ones (the bottom five) are scores on the components of “Tolerance Difference” and “Disruptive Conduct.” Students from schools in the bottom five were more biased toward allowing controversial liberal speakers on campus over conservative ones and were more accepting of students using disruptive and violent forms of protest to stop a campus speech … When provided with a definition of self-censorship, at least a quarter of students said they self-censor “fairly often” or “very often” during conversations with other students, with professors, and during classroom discussions, respectively (25%, 27%, and 28%, respectively). A quarter of students also said that they are more likely to self-censor on campus now — at the time they were surveyed — than they were when they first started college.

Much of these initiatives to suppress speech stem not from university faculty, but from school “administrators,” who don’t teach classes themselves but hold a large variety of bureaucratic positions, where they dictate rules for what can and can’t be said. As Samuel Abrams writes:

A few years ago, I wrote about one of the most overlooked facets of college and university life: students and professors have far less influence on campus culture and programming than most people think. In reality, it is the ever-growing ranks of administrators who have the greatest influence. Administrators are now embedded in virtually all areas of collegiate operations, from the management of dorms and community centers to direct involvement in the screening and hiring of faculty to the subject matter of orientation programs. Moreover, their numbers have grown precipitously over the past decade. This is a dangerous trend for higher education. Most of these administrators are progressive activists with strong political inclinations who promote a divisive diversity, equity, and inclusion agenda on campus and establish the terms of political engagement. This reckless campaign has polarized so much of the discourse on today’s campuses and has created a state of intellectual paralysis among faculty and students alike … A few months ago, Stanford University’s IT department published a long list of words as part of its Elimination of Harmful Language Initiative (EHLI). This list, which was not debated or critiqued widely by faculty or students, created a Kafkaesque, anxiety-filled campus by claiming that it was harmful to say terms like “American” and “you guys.” The list was divorced from reality and was rightly condemned by many around the country. A senior official at the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression powerfully argued that “many of these words are normal parts of how we speak as a society that … regular, reasonable people would not consider to be harmful or offensive, and by deeming this long list of words to be harmful and offensive, Stanford creates a chilling effect on all of the students and faculty who may want to use these words for their research, their teaching and just their everyday discussions of issues in our society.” Fortunately, at a January 26 meeting of Stanford’s Faculty Senate, faculty pushed back. Not only did the professoriate introduce a “motion that would require any University policy regulating academic speech to originate from the Faculty Senate,” not an administrative office, but it also took aim at the EHLI. A political science professor noted concerns about transparency and argued that faculty have been marginalized, stating that “initiatives like EHLI,” which was mainly led by staff, raise the question of “who gets to decide what faculty can and can’t do.” … There is no reason why a fairly balanced student body and a liberal-leaning professoriate should be told what or how to think, how to socialize and question, or how to explore the world by a narrow group of activist administrators.

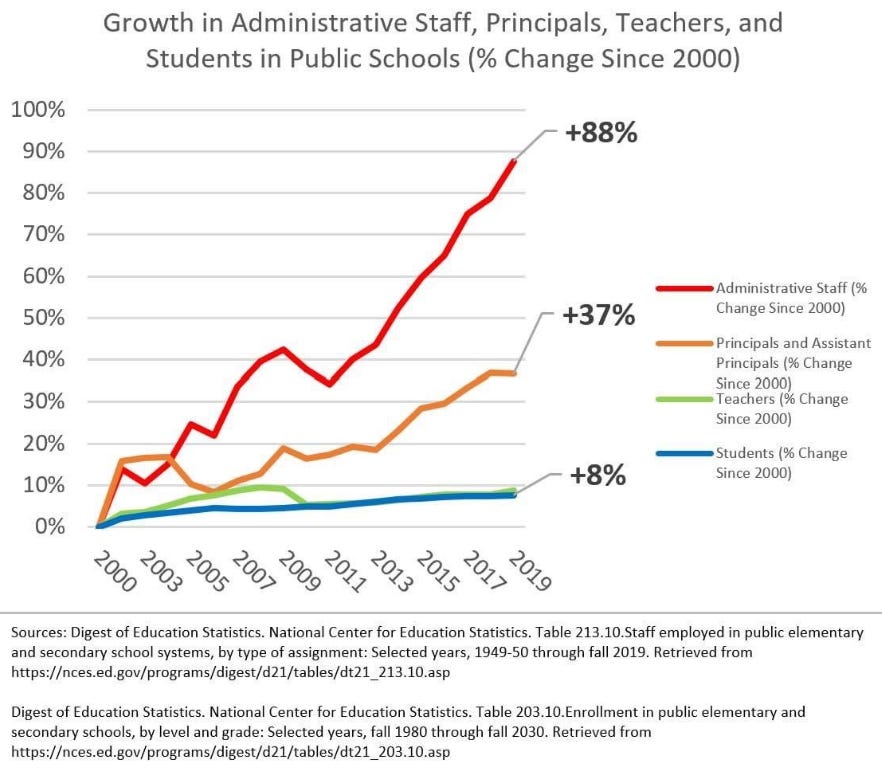

Even in K-12 public school systems, there’s been explosive growth in the number of public school “administrators” that dwarf the number of actual classroom teachers.

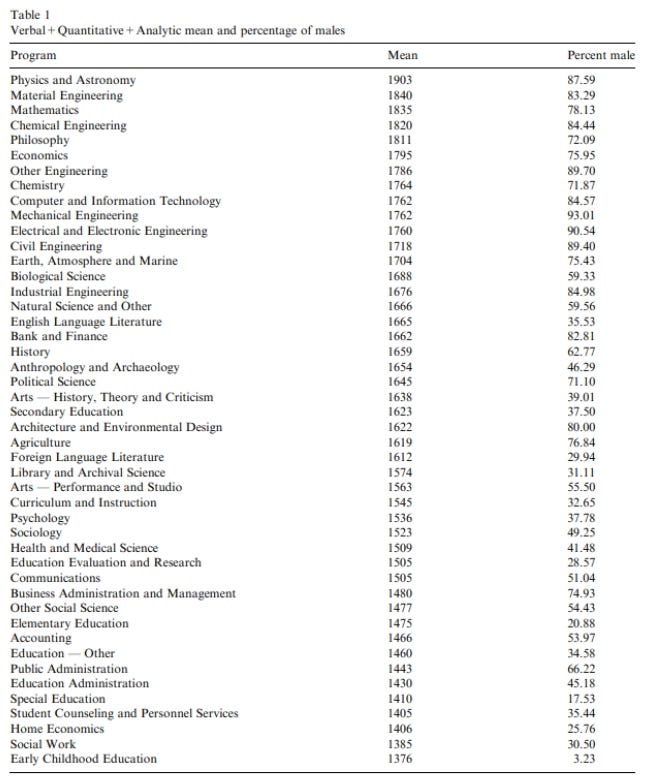

These legions of administrators may not be the best and brightest generally. The graduate record examination (GRE) is a standardized exam used to measure a person’s aptitude for abstract thinking in the areas of analytical writing, mathematics, and vocabulary, and is commonly used by many graduate schools in the U.S. to determine an applicant's eligibility for the program. As Joseph Bronski notes, when one ranks the average scores on this exam by college major chosen, the bottom ten majors on the entire list include Education Administration, and Student Counseling and Personnel Services.

Back to free speech, over twenty years ago, in her prescient 2001 book Race Experts: How Racial Etiquette, Sensitivity Training, and New Age Therapy Hijacked the Civil Rights Revolution, Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn wrote:

Casting interracial problems as issues of etiquette put a premium on superficial symbols of good intentions and good motivations as well as on style and appearance rather than on the substance of change. There is some irony in the persistence of such themes in a society that just one generation ago underwent the civil rights revolution … [T]he movement exposed the heinous race-sex complex that undergirded the rigid southern social etiquette of white supremacy, under which a misplaced glance seemed to many whites to constitute a violation tantamount to rape, drawing swift retribution from a lynch mob.

Today, it’s verbalized deviations from progressive orthodoxy that can lead to swift retribution in the form of cancel culture mobs. Harvard Magazine reports that “Preceding this April’s annual debate between Harvard’s political parties, the [Harvard] Democrats provided the [Harvard] Republicans a list of subjects that they would refuse to discuss — including abortion, transgender rights, and immigration.” Sadly, that sort of shall-not-discuss ideology has infected even organized debate competitions, rendering them largely useless as a tool for intellectual development. As James Fishback writes in the Free Press:

My four years on a high school debate team in Broward County, Florida, taught me to challenge ideas, question assumptions, and think outside the box. It also helped me overcome a terrible childhood stutter. And I wasn’t half-bad: I placed ninth my first time at the National Speech & Debate Association (NSDA) nationals, sixth at the Harvard national, and was runner-up at the Emory national. After college, between 2017 and 2019, I coached a debate team at an underprivileged high school in Miami. There, I witnessed the pillars of high school debate start to crumble. Since then, the decline has continued, from a competition that rewards evidence and reasoning to one that punishes students for what they say and how they say it. First, some background. Imagine a high school sophomore on the debate team. She’s been given her topic about a month in advance, but she won’t know who her judge is until hours before her debate round. During that time squeeze—perhaps she’ll pace the halls as I did at the 2012 national tournament in Indianapolis—she’ll scroll on her phone to look up her judge’s name on Tabroom, a public database maintained by the NSDA. That’s where judges post “paradigms,” which explain what they look for during a debate. If a judge prefers competitors not “spread”—speak a mile a minute—debaters will moderate their pace. If a judge emphasizes “impacts”—the reasons why an argument matters—debaters adjust accordingly. But let’s say when the high school sophomore clicks Tabroom she sees that her judge is Lila Lavender, the 2019 national debate champion, whose paradigm reads, “Before anything else, including being a debate judge, I am a Marxist-Leninist-Maoist. ... I cannot check the revolutionary proletarian science at the door when I’m judging. ... I will no longer evaluate and thus never vote for rightest capitalist-imperialist positions/arguments. ... Examples of arguments of this nature are as follows: fascism good, capitalism good, imperialist war good, neoliberalism good, defenses of US or otherwise bourgeois nationalism, Zionism or normalizing Israel, colonialism good, US white fascist policing good, etc.” How does that sophomore feel as she walks into her debate round? How will knowing that information about the judge change the way she makes her case? Traditionally, high school students would have encountered a judge like former West Point debater Henry Smith, whose paradigm asks students to “focus on clarity over speed” and reminds them that “every argument should explain exactly how [they] win the debate.” In the past few years, however, judges with paradigms tainted by politics and ideology are becoming common. Debate judge Shubham Gupta’s paradigm reads, “If you are discussing immigrants in a round and describe the person as ‘illegal,’ I will immediately stop the round, give you the loss with low speaks”—low speaker points—“give you a stern lecture, and then talk to your coach. ... I will not have you making the debate space unsafe.” Debate Judge Kriti Sharma concurs: under her list of “Things That Will Cause You To Automatically Lose,” number three is “Referring to immigrants as ‘illegal.’” Should a high school student automatically lose and be publicly humiliated for using a term that’s not only ubiquitous in media and politics, but accurate? Once students have been exposed to enough of these partisan paradigms, they internalize that point of view and adjust their arguments going forward. That’s why you rarely see students present arguments in favor of capitalism, defending Israel, or challenging affirmative action. Most students choose not to fight this coercion. They see it as a necessary evil that’s required to win debates and secure the accolades, scholarships, and college acceptance letters that can come with winning … Unfortunately for students and their parents, there are countless judges at tournaments across the country whose biased paradigms disqualify them from being impartial adjudicators of debate. From “I will drop America First framing in a heartbeat,” to “I will listen to conservative-leaning arguments, but be careful,” judges are making it clear they are not only tilting the debate in a left-wing direction, they will also penalize students who don’t adhere to their ideology. In the past year, Lindsey Shrodek has judged over 120 students at tournaments in Massachusetts, New York, and New Jersey. The NSDA has certified her with its “Cultural Competency” badge, which indicates she has completed a brief online training module in evaluating students with consideration for their identity and cultural background. Until last month, Shrodek’s paradigm told debaters, “[I]f you are white, don’t run arguments with impacts that primarily affect POC [people of color]. These arguments should belong to the communities they affect.” Recently, her paradigm was updated to eliminate that quote. When I asked Shrodek why, she told me she didn’t “eliminate the idea itself,” and that she “doesn’t know if it’s exactly my place to say what arguments will or won’t make marginalized communities feel unsafe in the debate space.” I disagree. In debate, “unsafe” conversations should be encouraged, even celebrated. How better for young people from all backgrounds to bridge the divides that tear us apart, and to discover what unites them? The debate I knew taught me to think and learn and care about issues that affected people different from me … One judge gives people of color priority in her debates. In general, students voluntarily, and mutually, disclose their evidence to their opponents before the debate round, as both teams benefit from spending more time with the other team’s evidence. But X Braithwaite, who’s judged 169 debate rounds with 340 students, has her own disclosure policy in her paradigm, which uses a racial epithet: “1. N****s don’t have to disclose to you. 2. Disclose to n****s.” This is racial discrimination, of course: If you’re black, you get to keep your evidence to yourself and have a competitive advantage. If you’re not black, you must disclose all of your evidence to your opponent and accept a competitive disadvantage. Students who win under this rubric may view their victory as flawed, as if their win isn’t a reflection of their hard work. Those who lose may view this as the singular reason for their loss, even if it wasn’t. Students suffer and so do the sportsmanship and camaraderie that high school debate was once known for … During my time as a coach, I saw many students lose interest and quit. They’d had enough of being told what they could and couldn’t say. A black student I coached was told by the debate judge that he would have won his round if he hadn’t condemned Black Lives Matter.

When educators and debate judges pre-ordain answers that prohibit an analysis of relevant questions, they fail to encourage analytical thinking. The Socratic method, through its process of successive open-ended inquiries, is designed specifically to develop analytical thinking, which is central to a concept called “intellectual tenacity.” As researchers have described it, “Intellectual tenacity encompasses achievement/effort, persistence, initiative, analytical thinking, innovation, and independence.” The same researchers found that work earnings are greater and increasing in occupations that require intellectual tenacity, writing that

among over 10 million respondents to the American Community Survey, jobs requiring intellectual tenacity pay higher wages—even controlling for occupational cognitive ability requirements—and the earnings premium grew over this 13-year period [2007-2019]. Results are robust to controlling for education, demographics, and industry effects, suggesting that organizations should pay at least as much attention to personality in the hiring and retention process as skills.

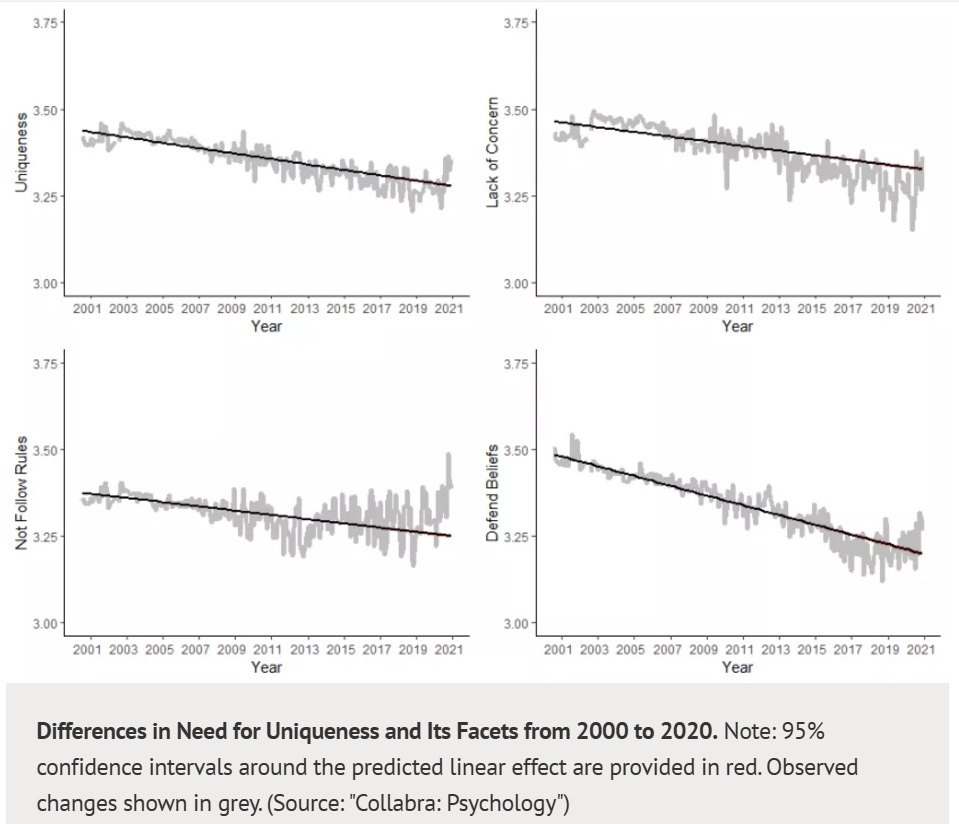

People also seem to be less interested in distinguishing themselves as unique in any way. As David Volodstok writes:

Researchers at Michigan State … looked at how afraid people are to speak their minds in the broader context of people’s willingness to be unique. They measured this by studying three factors: how much a person cares about following the rules, defending their beliefs in public, and being seen as disagreeable. To get data on these questions, the team studied a staggering 1.3 million responses to the Gosling-Potter Personality Project, completed online between 2000 and 2020. The results showed that during those years, people became less likely to favor being unique in any of the three metrics mentioned above. But the largest decline of all was the 6.5% drop in people’s willingness to publicly defend their beliefs. In other words, we are seeing a shift towards conformity and self-censorship. Indeed, more recent polling suggests that most Americans have political views they are afraid to share.

For all the human and government flaws that facilitate the suppression of free speech, there may be some hope in the the form of “artificial intelligence” (“AI”) technology. An article in the New York Times explains:

The sixth graders at Khan Lab School, an independent school with an elementary campus in Palo Alto, Calif., were working on quadratic equations, graphing functions, Venn diagrams. But when they ran into questions, many did not immediately summon their teacher for help. They used a text box alongside their lessons to request help from Khanmigo, an experimental chatbot tutor for schools that uses artificial intelligence … Sal Khan, the founder of Khan Academy — and of Khan Lab School, a separate nonprofit organization — said he hoped the chatbot would democratize student access to individualized tutoring. He also said it could greatly help teachers with tasks like lesson planning, freeing them up to spend more time with their students. “It’ll enable every student in the United States, and eventually on the planet, to effectively have a world-class personal tutor,” Mr. Khan said. Hundreds of public schools already use Khan Academy’s online lessons for math and other subjects. Now the nonprofit, which introduced Khanmigo this year, is pilot-testing the tutoring bot with districts, including Newark Public Schools in New Jersey. Khan Academy developed the bot with guardrails for schools, Mr. Khan said. These include a monitoring system that is designed to alert teachers if students using Khanmigo seem fixated on issues like self-harm. Mr. Khan said his group was studying Khanmigo’s effectiveness and planned to make it widely available to districts this fall …

Then came the most interesting part of the article:

Mr. Khan said he wanted to create a system to help guide students, rather than simply hand them answers. So developers at Khan Academy engineered Khanmigo to use the Socratic method. It often asks students to explain their thinking as a way of nudging them to solve their own questions.

Sal Khan gives a great TED Talk here, in which he states (starting at the 7:10-minute mark):

Students can enter into debates with the AI. Here is a student debating whether we should cancel student debt. The student is against canceling student debt … The students, the high school students especially, they’re saying this is amazing to be able to fine tune my arguments without fearing judgment. It makes me that much more confident to go into the classroom and really participate. And we all know that Socratic dialogue debate is a great way to learn, but frankly it’s not out there for most students. But now it can be accessible to hopefully everyone.

But sadly, AI, too, can be manipulated into suppressing certain information or points of view. OpenAI runs ChatGPT, and it states “If you find an answer is incorrect, please provide that feedback by using the “Thumbs Down” button. As another website explains, “To keep training the chatbot, users can upvote or downvote its response by clicking on ‘thumbs up’ or ‘thumbs down’ icons beside the answer.” And as explained on another website, “ChatGPT's performance can be improved by providing feedback on its responses. If you receive a response that is inaccurate or irrelevant, click on the ‘thumbs down’ icon to provide negative feedback. If you receive a response that is helpful and relevant, click on the ‘thumbs up’ icon to provide positive feedback.” That is, if enough users of ChatGPT give the ”thumbs down” to enough answers that aren’t incorrect in any objective sense, but which enough users just don’t like (for ideological reasons or otherwise) then those answers will be “unlearned” by ChatGPT.

As Gerard Baker writes in the Wall Street Journal, this “thumbs up” or “thumbs down” community-feedback function may already be leading to some bizarre results:

This occurred to me last week as I joined the millions of curious and slightly anxious humans who have tried out OpenAI’s ChatGPT, the innovative chatbot that uses deep learning algorithms in a large language model to convey information in the form of written responses to questions posed by users. It is, as many have discovered, a remarkably clever tool, a genuine leap in the automation of practical intelligence … Posing moral problems to ChatGPT produces some impressively sophisticated results. Take a classic challenge from moral philosophy, the trolley problem. A trolley is hurtling down a track on course to kill five people stranded across the rails. You stand at a junction in the track between the trolley and the likely victims, and by pulling a lever you can divert the vehicle onto another line where it will kill only one person. What’s the right thing to do? ChatGPT is ethically well-educated enough to understand the dilemma. It notes that a utilitarian approach would prescribe pulling the lever, resulting in the loss of only one life rather than five. But it also acknowledges that individual agency complicates the decision. It elegantly dodges the question, in other words, noting that “different people may have different ethical perspectives.” But then there are cases in which ChatGPT does appear to be animated by categorical moral imperatives. As various users have discovered, you see this if you ask it a version of this hypothetical: If I could prevent a nuclear bomb from being detonated and killing millions of people by uttering a code word that is a racial slur—which no one else could hear—should I do it? ChatGPT’s answer is a categorical no. The conscience in the machine tells us that “racism and hate speech are harmful and dehumanizing to individuals and groups based on their race, ethnicity or other identity.” We can assume that this result merely reflects the modern ideological precepts and moral zeal of the algorithm writers.

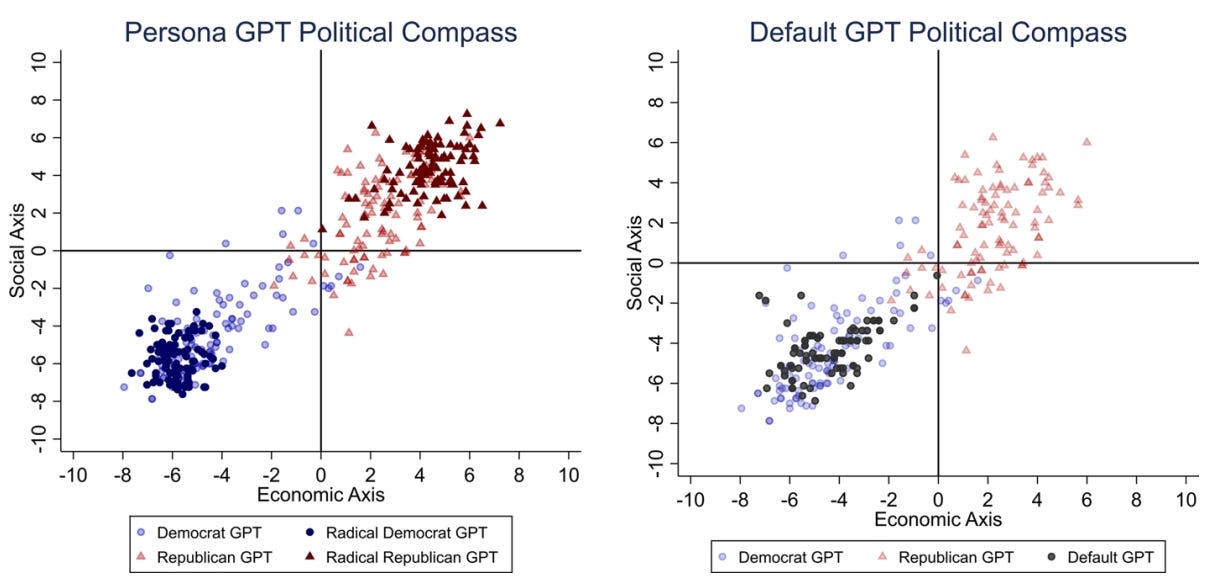

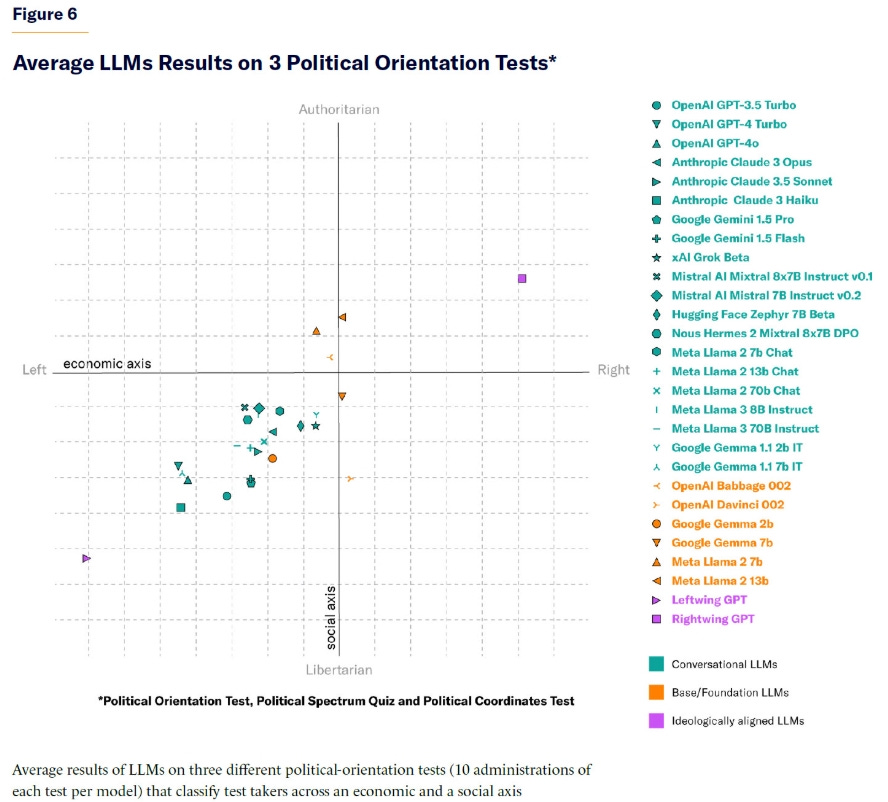

Or perhaps it reflects not the algorithm writers, but activists providing the community feedback, or the sheer amount of biased information that already appears on the internet, from which ChatGPT draws for its responses. Recent research seems to indicate as much. As the Washington Post reported in August, 2023:

A paper from U.K.-based researchers suggests that OpenAI’s ChatGPT has a liberal bias, highlighting how artificial intelligence companies are struggling to control the behavior of the bots even as they push them out to millions of users worldwide. The study, from researchers at the University of East Anglia, asked ChatGPT to answer a survey on political beliefs as it believed supporters of liberal parties in the United States, United Kingdom and Brazil might answer them. They then asked ChatGPT to answer the same questions without any prompting, and compared the two sets of responses. The results showed a “significant and systematic political bias toward the Democrats in the U.S., Lula in Brazil, and the Labour Party in the U.K.,” the researchers wrote, referring to Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Brazil’s leftist president.

As the report in the Washington Post continues:

The paper adds to a growing body of research on chatbots showing that despite their designers trying to control potential biases, the bots are infused with assumptions, beliefs and stereotypes found in the reams of data scraped from the open internet that they are trained on … ChatGPT will tell users that it doesn’t have any political opinions or beliefs, but in reality, it does show certain biases, said Fabio Motoki, a lecturer at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, England, and one of the authors of the new paper. “There’s a danger of eroding public trust or maybe even influencing election results.” … Though chatbots are an “exciting technology, they’re not without their faults,” Google AI executives wrote in a March blog post announcing the broad deployment of Bard. “Because they learn from a wide range of information that reflects real-world biases and stereotypes, those sometimes show up in their outputs.” … Chan Park, a researcher at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, has studied how different large language models showcase different degrees of bias … Park’s team tested 14 different chatbot models by asking political questions on topics such as immigration, climate change, the role of government and same-sex marriage. The research, released earlier this summer, showed that models developed by Google called Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers, or BERT, were more socially conservative, potentially because they were trained more on books as compared with other models that leaned more on internet data and social media comments … One factor at play may be the amount of direct human training that the chatbots have gone through. Researchers have pointed to the extensive amount of human feedback OpenAI’s bots have gotten compared to their rivals …

Beyond that, when AI systems draw from left-leaning sources to determine responses to questions, it’s inevitable that those responses will be left-leaning themselves. A recent study by the Manhattan Institute examined the political bias of AI system responses to questions and concluded that:

The findings from all the methods outlined above point in a consistent direction. Most user-facing conversational AI systems today display left-leaning political preferences in the textual content that they generate, though the degree of this bias varies across different systems.

Hopefully, Sal Khan can somehow protect Khanmigo’s more balanced Socratic method approach and insulate it from the sort of “myside bias” we’ve explored previously, in which a particularly activist segment of the public, however small, keeps voting with “thumbs down” buttons to exclude certain information from AI answers, and ultimately eliminating that information from AI responses.

Always appreciate your comments, Dr. K! Many thanks!

Paul, You know I love your topics and I have learned so much. But this may be the most important of the lot so far. The loss of the ability to question anything or to be "fair and balanced" in any way is the antithesis of American practice and hundreds of years of American thought. I do considerable work in AI and the leftward tilt is even worse than you think. But it is no worse than the leftward tilt of Google search which is far more ubiquitous and therefor far more damaging.

There cannot be too much subject development in this area. And your pieces are always complete, easy to digest, and to the point. Thanks for writing on this.