As I’ve mentioned previously, in our local public school system, there’s an official definition of “educational equity” in a document called the 2025 Equity for All Strategic Plan, and that definition states “educational equity” means “Positive school outcomes are distributed equitably proportionally across all demographic and identity groups. Negative outcomes and disproportionality are reduced for all groups.” What that means is that “positive school outcomes” need to be distributed by race in proportion to racial demographics. So, for example, say the demographic breakdown of a class of students is as follows: 7% of the class is purple; 30% of the class is green; 34% of the class is orange; and 29% of the class is blue. “Educational equity” would mean that it was the public school system’s policy that 7% of the purple students had “positive school outcomes,” 30% of the green students would have such outcomes; 34% of orange students would have such outcomes; and 29% of the blue students would have such outcomes. Also as discussed in a previous essay, such a policy is patently unconstitutional under current Supreme Court precedent. Be that as it may, such “equity” policies remains on the books in many jurisdictions and in many contexts. Ironically, while such “equity” policies are often justified on the grounds that they somehow help “remedy systemic racism,” in fact they constitute systemic racism itself. And more than that, such policies are based on a systemic error, namely that racial demographic disparities in various outcomes must be based on racism, rather than on many other factors which we know result in, and explain, racial demographic disparities. The failure to see that many other factors explain racial disparities is itself a systemic error (that is, a systemic bias) that permeates so-called “equity” plans.

One significant factor that leads to racial disparities in outcomes is whether a person is raised by one or two people, with the presence of two parents rather than one significantly influencing the amount of additional supervision, parental education, and resources a person might benefit from growing up. This essay discusses some more recent findings on the true causes of racial disparities.

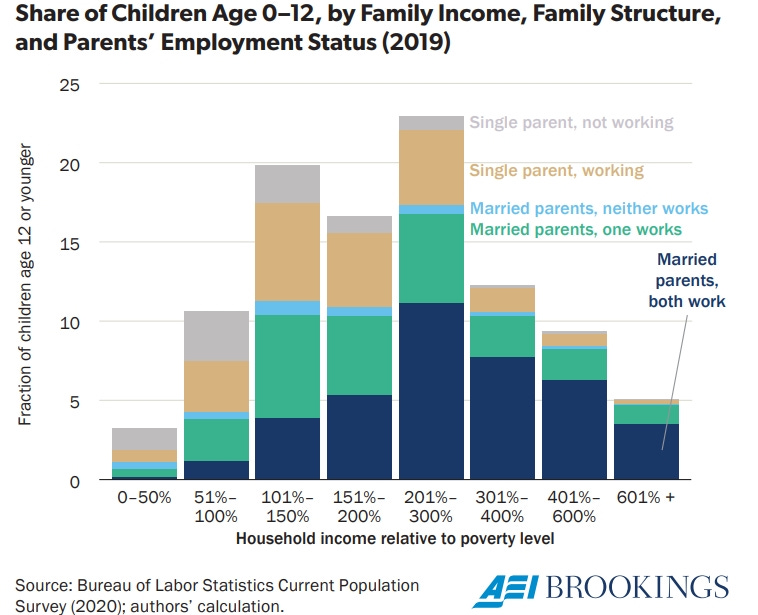

Researchers at both the American Enterprise Institute and the Brookings Institution concluded that:

[J]ust over one-third of the lowest-income families have married heads-of household, while 91 percent of the highest-income families do. More than half of the children ages 12 and under in the lowest-income families live in families headed by single parents, compared with only 6 percent of those in the highest-income families. In addition to family structure, the employment status of adults in the family is self-evidently and strongly related to income. The figure shows that 92 percent of the children in families with incomes over the poverty threshold had at least one worker in 2019. Notably, for 63 percent of the children in families with income above the poverty line—and nearly 60 percent of children overall—all parents in the family are employed.”

In 2018 more Black children lived with never-married mothers than with married parents. Fewer than two in five Black children lived with married parents in 2018, compared with two in three Hispanic children and 82 percent of white children.

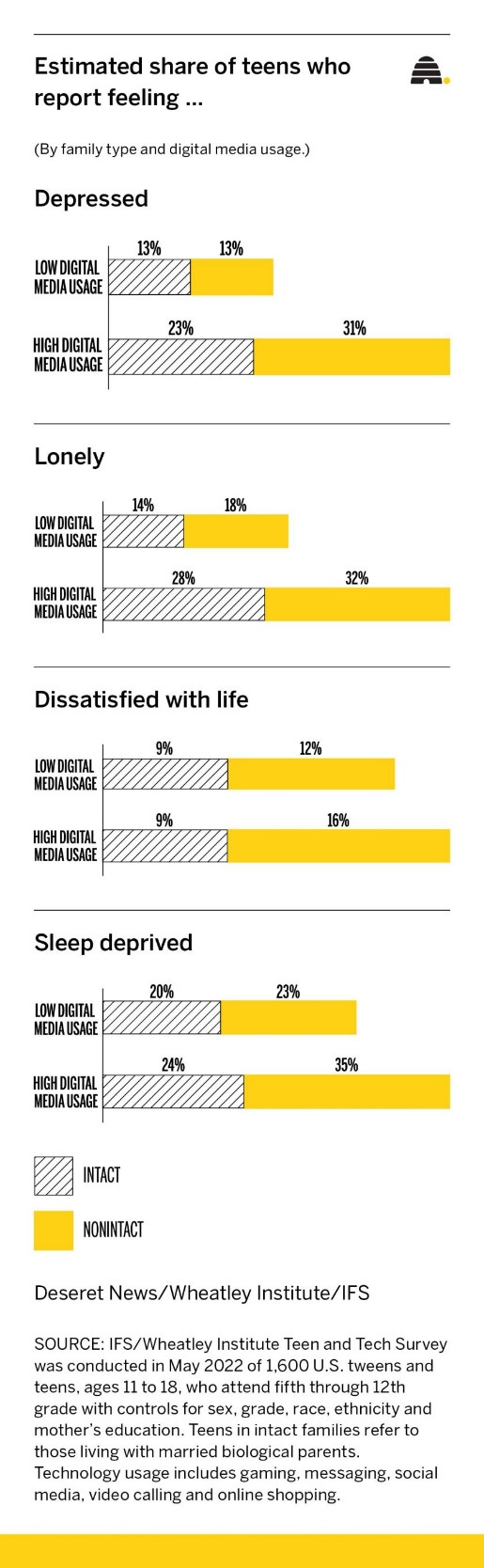

Kids who live in single-parent households are also more likely to use social media more, with a tendency to experience more of the negative results from excessive social media use. As Jenet Erickson and Brad Wilcox explain:

A new report from the Institute for Family Studies and the Wheatley Institute — “Teens and Tech: What Difference Does Family Structure Make?” — identifies another vulnerable group: those in stepparent and single-parent families. This national survey of 1,600 U.S. 11- to 18-year-olds found that youth in nonintact families spent about two hours a day more on digital media than those living with their married biological parents. Youth living in stepfamilies spent the most time on digital media.

Family type did not predict greater likelihood of depression for youth who were lighter users of digital media. But for heavy users (eight-plus hours a day), the youth most likely to be depressed were those in nonintact families. The same was true of loneliness. Youth who were heavy users of digital media were more likely to report high levels of loneliness, with the highest percentage among heavy users in nonintact families. A similar pattern emerged for feelings of dissatisfaction with life where there was a stronger link between media use and dissatisfaction for youth in nonintact families. What all of these findings indicate is that youth in nonintact families are spending more time with digital media and experiencing more negative effects from it when they use it a lot. Part of this is because intact families had more rules around technology use, including not allowing devices in bedrooms or during family meals. They were also more likely to do family activities like playing games, being outdoors or eating dinner without digital distraction.

Interestingly, as Kristin Downey writes in The Woman Behind the New Deal: The Life of Frances Perkins, FDR'S Secretary of Labor and His Moral Conscience, a biography of the woman who shepherded the first modern American labor laws through Congress in the 1930’s, the increase in single parent families was the inadvertent result of expanded welfare laws:

[O]nly 3.8 percent of children in female-headed households were illegitimate in 1930, with most mothers having lost their husbands through death or desertion. Frances [Frances Perkins, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Secretary of Labor] believed that women needed and deserved reliable support to raise their children and that child rearing is itself a full-time job. She never guessed that there would later be an explosion of out-of-wedlock births because she had grown up believing the stigma of bearing illegitimate children would far outweigh any economic incentives that were built into the new legislation. Over the next few decades, however, impoverished women found that they could get more money from the government by having more children while households in which a man was a full-time resident got no aid at all. This perverse policy had been intended to encourage men to seek gainful employment and support their families, but it had the side effect of discouraging marriage in the first place, spurring even more illegitimate babies, and removing adult men from households that needed them.

Regarding the extent of the problem of boys growing up in households without fathers, Brad Wilcox and Wendy Wang write:

The percentage of boys living apart from their biological father has almost doubled since 1960—from about 17% to 32% today; now, an estimated 12 million boys are growing up in families without their biological father. Specifically, approximately 62.5% of boys under 18 are living in an intact-biological family, 1.7% are living in a step-family with their biological father and step- or adoptive mother, 4.2% are living with their single, biological father, and 31.5% are living in a home without their biological father. Lacking the day-to-day involvement, guidance, and positive example of their father in the home, and the financial advantages associated with having him in the household, these boys are more likely to act up, lash out, flounder in school, and fail at work as they move into adolescence and adulthood. Even though not all fathers play a positive role in their children’s lives, on average, boys benefit from having a present and involved father. This Institute for Family Studies research brief details the connections between fatherlessness, family structure, and the increasing number of young men who are floundering in life and pose a threat to themselves and their communities. We do so by exploring the links between family structure and college completion, idleness (defined here as twenty-somethings not in school or working), and involvement with the criminal justice system (measured by arrests and incarceration) for young men in the 2000s and 2010s, using the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1997 (NLSY97). We specifically examine how young men who were raised in a home with their biological father compare on these outcomes to their peers in families without their biological father. Here is what we found … Boys today are struggling at all levels of school, falling behind girls in reading and math skills, and are less likely than girls to graduate high school on time. Young men are also less likely than young women to attend or graduate from college. When we think about the many factors behind this gender gap, family structure is often not the first cause to come to mind. But as MIT economist David Autor has found, the gender gap in high school, including suspensions and graduation, is larger for boys who did not grow up in married families compared to boys who did. In this brief, we examine how the presence of a biological father in the home is linked to a young man’s chances of earning a college degree. As the figure below shows, when it comes to higher education for young men, family structure seems to matter. Young men who grew up with their biological father are more than twice as likely to graduate college by their late-20s, compared to those raised in families without their biological father (35% vs. 14%). Even after controlling for race, family income growing up, maternal education, age, and an AFQT score (a measure of general knowledge), we still see that hailing from a home with his own biological father doubles the likelihood that a young man will graduate from college.

A college degree is not the only measure of success. In fact, getting at least a high school degree and then a full-time job are two key steps toward avoiding poverty as adults. Unfortunately, more and more young men today are floundering without purpose and without work. As Nicholas Eberstadt and Evan Abramsky have reported, the U.S. has seen a surge in the number of prime-age men who are not currently working or looking for work: prior to the pandemic, nearly 7 million men between the ages of 25 and 54 were not working at all. The daily life of these men is often marked by hours in front of a screen while vaping, smoking marijuana, or under the influence of some other kind of substance.

… As the above figure illustrates, young men who did not grow up with their biological father are significantly more likely to be idle in their mid-20s compared to young men who did grow up with their biological father (19% vs. 11%). After controlling for family income growing up, race, maternal education, age, and AFQT, we find that young men who did not grow up with their biological father are almost twice as likely to be idle compared to their male peers from father-present families … Of course, dads do more than just help their sons pursue an education and become productive members of society—they also play a major role in keeping their sons out of trouble. Research tells us that involved and present fathers reduce the odds that young men become a threat to society. Warren Farrell, author of The Boy Crisis, puts it this way: “Boys with dad-deprivation often experience a volcano of festering anger … And with boys’ much greater tendency to act out, the boys who hurt will be the ones most likely to hurt us.”

This figure illustrates his point. In addition to being markedly more likely to have been arrested during their teen years, young men who did not grow up with their father in the home are about twice as likely as those raised with their biological father in the household to have spent time in jail by around age 30. These associations remain strong and statistically significant even after controlling for family income, race, maternal education, age, and AFQT scores.

Ignoring these facts and instead falsely assuming that racial disparities are the result of racism, and enacting policy on that false premise, can lead to absurd results. To take one example described by the Wall Street Journal:

The law of unintended consequences refers to government actions that have unanticipated outcomes … [I]t’s why New York’s clumsy effort to legalize the recreational use of marijuana in the name of social justice has turned into a farce. Two years ago, New York passed the Marijuana Regulation and Taxation Act and became one of nearly two dozen states that have authorized the sale of pot. Gov. Kathy Hochul has said that the law is about “creating jobs and opportunities” and “supporting small businesses.” Proponents estimate that legal marijuana sales will generate $4 billion over the next five years. A “major focus” of the law, according to the state’s new Office of Cannabis Management, “is social and economic equity.” Hence, half of all retail licenses are reserved for minorities, women, distressed farmers, veterans and “individuals disproportionally impacted” by the war on drugs. People with marijuana-related convictions get first dibs on the new permits, and hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars will be directed toward helping them purchase and renovate storefronts to peddle cannabis products. The same lawmakers who refuse to expand education options for low-income minorities trapped in failing schools are eager to help former drug dealers get back in the game. New York City’s first legal marijuana dispensary opened in December, but government bureaucrats aren’t known for their expeditiousness, and the licensing rollout has been pitifully slow. The upshot is the growth of a sizable black market of unregulated pot dispensaries, including the Jungle Boys weed shop across the street from City Hall in lower Manhattan. The store has been raided twice by police since opening in the fall, according to the New York Post. But “like most of the other roughly 1,400 illegal cannabis shops operating citywide, Jungle Boys’ operators were undeterred.” They restocked the shelves and reopened two weeks after the raids. Like his counterparts in Chicago and Philadelphia, progressive Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg has taken a lax attitude toward prosecuting violent repeat offenders, even as the city’s crime rate has risen. Yet now he says his office can’t abide unlawful pot shops. Last week, Mr. Bragg announced a new partnership with local law enforcement and elected officials to crack down on the illegal businesses. “It’s time for the operation of unlicensed cannabis dispensaries to end,” Mr. Bragg said. But isn’t a crackdown on illegal dispensaries at cross-purposes with the equity aims of the new law? Proponents wanted to legalize pot in the first place because blacks and Hispanics are arrested for drug offenses at higher rates than whites. By design, many of the people operating these pot shops are waiting for licenses that are reserved for racial and ethnic minorities. If Mr. Bragg is serious about going after them, he will inevitably be targeting the same groups that were disproportionately targeted under the old law.

“Equity”-based policies now permeate federal law. As the Wall Street Journal reports:

President Biden has adopted the left’s approach to race, which means detecting bias even where none exists. One example is his embrace of a rule that enacts a presumption of guilt in race-based litigation. The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) recently finalized its “discriminatory effects standard,” a new version of a policy already in effect … The original law bans discrimination in home sales, rentals and financing, but it defines violations straightforwardly, requiring complainants to show how they were penalized. HUD’s rule shifts the burden of proof to the accused. It considers landlords, lenders and developers to be guilty of discrimination if any of their policies causes unequal outcomes for a protected class, regardless of intent. This standard of culpability, known as disparate impact, subjects businesses to punishment for ordinary practices. A statistical disparity can be proof of bias even without evidence of discriminatory practices. Lending to too few minorities could invite litigation, even if credit worthiness and not race is the reason for the deficit.

As the Wall Street Journal reports, the Biden Administration is now pursuing a new “disparate impact” approach to internet service:

The Federal Communication Commission’s new Democratic majority is up and running and firing in all directions. Next week the Commission plans to vote on a proposed “digital discrimination” rule. In the name of equity, Democratic Commissioners will make internet service worse. The 2021 infrastructure bill instructed the FCC to prevent “digital discrimination” of broadband access “based on income level, race, ethnicity, color, religion, or national origin.” While the statutory language is broad, the agency’s proposed rule stretches it further to force broadband providers to prioritize identity politics. The FCC concedes that it has found “little or no evidence” indicating “intentional discrimination by industry participants.” No problem. The agency will still hold broadband providers liable for actions or “omissions” that result in a disparate impact on an identity group. That means providers could be dunned if regulators or third-party groups (read: progressive lobbies) identify statistical disparities in a long list of “covered service elements” even if they don’t intentionally discriminate. The rule would give the FCC power to micromanage the industry. Marketing materials that feature too many white people could be ruled discriminatory. Companies could be forced to scrap credit checks that cause more minorities to be rejected for smartphone leasing plans. Providers could even be punished for charging the same prices to all customers since their rates might have a disparate financial impact on minorities. The FCC could likewise prohibit low-cost wireless plans that include data caps because these are selected more often by people with lower incomes. If you think these are unlikely, you haven’t been watching the left. Wireless carriers might also be prohibited from building out 5G networks in suburbs and city downtowns before inner cities and rural areas. Companies don’t have unlimited capital so they typically prioritize network upgrades in areas where they can earn a higher return on the investment, which they then use to finance improvements in lower-income and rural areas. Yet companies wouldn’t be allowed to invoke profitability concerns in defense of practices with a disparate impact. They would have to prove that their policies are “justified by genuine issues of technical or economic feasibility.” They couldn’t claim that an alternative, allegedly less discriminatory, policy would cause them to lose money.

These “equity”-based policies are being implemented even as many presumptions of racism are being shown to be false. As Alex Tabbarok describes a recent study:

There have now been lots of resume-audit studies in which identical resumes but for the “minority-distinct” name are sent out to employers and callback rates are measured. A meta-study of 97 field experiments (N = 200,000 job applicants) in 9 countries in Europe and North America finds there is some discrimination in every county but, if anything, the USA has one of the lower rates of discrimination while France and perhaps also Sweden have very high levels. These result’s aren’t that surprising to those who travel but they run counter to the narrative that the US is uniquely or especially discriminatory because of its history of slavery and capitalism. Capitalism, in fact, is likely to predict less discrimination. A picture summarizes. The US is here defined as 1 and these are relative levels after controlling for some basic differences across studies:

Among the points made by the study authors are the following:

[N]ational histories of slavery and colonialism are neither necessary nor sufficient conditions for a country to have relatively high levels of labor market discrimination. Some countries with colonial pasts demonstrate high rates of hiring discrimination, but several countries without extensive colonial pasts (outside Europe), such as Sweden, demonstrate similar levels. Likewise, the lower rates of discrimination against minorities in the United States than we find for many European countries seem contrary to expectations that emphasize the primacy of connection to slavery in shaping the contemporary level of national discrimination.

And as Jason Riley writes in the Wall Street Journal:

Ta-Nehisi Coates’s 2014 article in the Atlantic magazine … is titled “The Case for Reparations.” That case is largely based on housing discrimination in the Jim Crow era. “Redlining went beyond FHA-backed loans and spread to the entire mortgage industry,” he wrote, “which was already rife with racism, excluding black people from most legitimate means of obtaining a mortgage.” … [T]he argument that discriminatory housing policies kept blacks from acquiring more wealth and entitle them to reparations isn’t a particularly strong one. Mr. Coates asserts that government’s housing policies “engineered the wealth gap” that exists today. The historical reality is that notwithstanding the difficulties blacks faced in obtaining mortgages in the postwar period, homeownership among blacks was rising faster than it was among whites. Research by economists William J. Collins and Robert A. Margo shows that between 1940 and 1980, homeownership rates climbed by 37 percentage points for blacks and by 34 points for whites. If homeownership builds wealth, this was a period of extraordinary gains for blacks. But there is a more fundamental problem with linking reparations to past redlining policies. While a higher percentage of the black population lived in redlined areas, most residents of neighborhoods where the FHA refused to insure mortgages weren’t black, according to a 2021 National Bureau of Economic Research study by Price V. Fishback, Jessica LaVoice, Allison Shertzer and Randall Walsh. “In our sample, over 95 percent of black homeowners lived in the lowest-rated ‘D’ zones,” they found. “Yet, the vast majority (92 percent) of the total redlined home-owning population was white.” If being a victim of redlining is a qualification for reparations, what is the argument for excluding whites?

As Robert Cherry writes:

To be sure, racial disparities in home ownership rates persist. But a significant share can be explained by family structure. In 2022, overall black homeownership was 44 percent; but for married couples it was 64 percent, virtually the same as the overall white homeownership rate. Moreover, in the last thirty years, the suburbanization process has had a dramatic effect on the residential location of the black middle class. Today, more than 54% of all black Americans residing in the 60 largest metropolitan area lives in suburbs. Researchers concluded: “The study’s findings essentially show two Black Americas: Black suburbanites increasingly living in more integrated neighborhoods with higher-quality indicators and lower income Black city dwellers seeing their neighborhood characteristics stagnate or worsen.”

Researchers at the Federal Reserve found that black households also tend to be congregated because many black homeowners prefers to live near other black homeowners, regardless of the socioeconomic status of the neighborhood. The researchers write:

Why do Black households live in neighborhoods with much lower socioeconomic status (SES) than the neighborhoods of white households with similar incomes? The explanation is not wealth. High-income, high-wealth Black households live in neighborhoods with similar SES as low-income, low-wealth white households. Instead, we provide evidence that many Black households prefer low-SES neighborhoods with Black residents to high-SES neighborhoods without Black residents.

“Equity”-based rationales for weakening criminal penalties also produce perverse results. As Jason Riley writes in the Wall Street Journal:

Mayor Eric Adams was back in Albany this month asking his state overlords to rethink bail-reform measures passed in 2019 that protect crime suspects from pretrial detention. The number of shoplifting complaints in New York City rose by 45% in 2022 to more than 63,000, according to New York City Police Department data. The mayor sees an obvious connection that too many of his fellow liberal Democrats willfully ignore. In his testimony, Mr. Adams argued that soft-on-crime policies hit poor communities the hardest, not only in terms of public safety but also economically. “When you do a real analysis in our pursuit of making sure people who commit crimes are receiving the justice they deserve, we can’t forget the people who are the victims of crimes,” he said … The belief that poverty is the root cause of crime may be popular, but it doesn’t hold up to scrutiny. For starters, most poor people aren’t criminals. In a previous era, when Americans were significantly poorer than they are today, crime rates were significantly lower. Crime during the Great Depression was lower than during the 1960s, a decade of tremendous economic growth and prosperity. In 1960 the black male homicide rate was 45 per 100,000. By 1990 it had climbed by more than 200% to 140 per 100,000, even though black average incomes by then were much higher, and the black poverty rate much lower, than 30 years earlier. In a recently published book about criminal-justice reform, “Criminal (In)justice,” Rafael Mangual notes that this disconnect between crime and poverty continues today. Mr. Mangual writes that between 1990 and 2018, murders in New York City declined by 87%, a period during which the city’s poverty rate increased slightly. Black residents today “experience poverty at a lower rate (19.2 percent) than their Hispanic (23.9 percent) and Asian (24.1 percent) counterparts, who account for much smaller shares of the city’s gun violence.” … In his testimony, Mr. Adams called public safety “the prerequisite to our prosperity” and stressed that the problem isn’t previously law-abiding New Yorkers turning to crime but career criminals running rampant with no fear of being prosecuted. “This is critical because a disproportionate share of the serious crime in New York City is being driven by a limited number of extreme recidivists,” he said. “Approximately 2,000 people who commit crime after crime while out on the street on bail.”

“Soft on crime” policies based on “equity” rationales may be popular among certain political leaders, but black citizens, including the large majority of black Democrats, don’t agree. A 2022 poll by the Pew Research Center found that “Differences by race are especially pronounced among Democratic registered voters. While 82% of Black Democratic voters say violent crime is very important to their vote this year, only a third of White Democratic voters say the same.” As the Wall Street Journal writes, “That’s not surprising when you consider that black Americans are disproportionately the victims of the soft-on-crime approach favored by Democratic politicians and prosecutors in crime-ridden big cities.”

In many cities, black residents are not only the disproportionate victims of crime, but they also suffer from higher prices caused by the costs of crime to local businesses. As the Wall Street Journal points out:

[T]he cost of shoplifting on stores and paying customers is also on the rise. “We’ve seen a significant increase in theft and organized retail crime across our business,” a Target executive said in an earnings call last month. The damage to the company’s gross margin for this year is estimated at $600 million. Rite Aid said in an earnings call this month that retail theft, compared with the same quarter last year, “was $9 million worse,” and it’s likely “to be a continued headwind.” Chief Retail Officer Andre Persaud said this fall that “the headline here is the environment that we operate in, particularly in New York City, is not conducive to reducing shrink”—an industry euphemism for missing or damaged goods. Many Big Apple drugstores now put even toothpaste and deodorant behind lock and key. In February one Rite Aid in Manhattan was forced to close after “brazen thieves stole more than $200,000 in merchandise in December and January alone,” the New York Post reported. One employee described how shoplifters “come in every day, sometimes twice a day, with laundry bags and just load up on stuff,” and “we can’t do anything about it.” Walmart CEO Doug McMillon described the consequences in an interview with CNBC this month. If the epidemic of retail theft is “not corrected over time, prices will be higher and/or stores will close.” In a U.S. Chamber of Commerce survey this fall, 46% of small retailers said they’d been “forced to increase their prices over the past year as a result of shoplifting.” Some chains hire private security, but that’s another cost to recoup at the checkout line. The shoplifting scourge is rooted in a lack of enforcement. After George Floyd’s murder in 2020, urban Democrats voted to slash police budgets, and cops quit in droves. Police departments that are forced into triage mode will understandably prioritize violent crime above shoplifting. Progressives have also pushed to raise the threshold for shoplifting to be treated as a felony. As of 2019, according to data from the National Association for Shoplifting Prevention, a thief could steal $999 or less in 21 states and face a mere misdemeanor; in five states, the felony threshold was $2,000 or higher.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll examine more information regarding why the premise of “equity”-based remedies – namely, that they’re justified by a sort of tit-for-tat, “us” versus “them” mentality – doesn’t accurately reflect history.

Paul, Some of this is frankly scandalous. I am amazed every time you pen one of these pieces how much information is deliberately ignored by virtually everyone. Trying to figure out what can be done about it all...sheesh. Thanks much.