Randomness -- Part 5

The randomness of aesthetics.

In this essay, we’ll further explore the role of randomness in people’s lives and focus on some of the randomness that occurs in the area of aesthetics and entertainment, using Nassim Taleb’s Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of Chance in Life and Markets, and Leonard Mlodinow’s The Drunkard’s Walk: How Randomness Rules Our Lives.

Mlodinow recounts the following interesting example:

Imagine that George Lucas makes a new Star Wars film and in one test market decides to perform a crazy experiment. He releases the identical film under two titles: Star Wars: Episode A and Star Wars: Episode B. Each film has its own marketing campaign and distribution schedule, with the corresponding details identical except that the trailers and ads for one film say Episode A and those for the other, Episode B. Now we make a contest out of it. Which film will be more popular? Say we look at the first 20,000 moviegoers and record the film they choose to see (ignoring those die- hard fans who will go to both and then insist there were subtle but meaningful differences between the two). Since the films and their marketing campaigns are identical, we can mathematically model the game this way: Imagine lining up all the viewers in a row and flipping a coin for each viewer in turn. If the coin lands heads up, he or she sees Episode A; if the coin lands tails up, it’s Episode B. Because the coin has an equal chance of coming up either way, you might think that in this experimental box office war each film should be in the lead about half the time. But the mathematics of randomness says otherwise: the most probable number of changes in the lead is 0, and it is 88 times more probable that one of the two films will lead through all 20,000 customers than it is that, say, the lead continuously seesaws. [See William Feller, An Introduction to Probability Theory and Its Applications, 2nd edition (1957) at p. 68.] The lesson is not that there is no difference between films but that some films will do better than others even if all the films are identical … Such issues are not discussed in corporate boardrooms, in Hollywood, or elsewhere, and so the typical patterns of randomness— apparent hot or cold streaks or the bunching of data into clusters— are routinely misinterpreted and, worse, acted on as if they represented a new trend.

The same phenomenon has been studied in music trends. As Mlodinow writes:

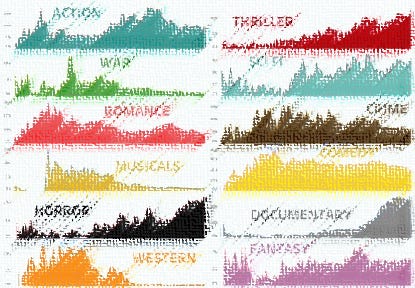

The same phenomenon has been noticed by researchers in sociology. One group, for example, studied the buying habits of consumers in what sociologists call the cultural industries—books, film, art, music. The conventional marketing wisdom in those fields is that success is achieved by anticipating consumer preference. In this view the most productive way for executives to spend their time is to study what it is about the likes of Stephen King, Madonna, or Bruce Willis that appeals to so many fans. They study the past and, as I’ve just argued, have no trouble extracting reasons for whatever success they are attempting to explain. They then try to replicate it. That is the deterministic view of the marketplace, a view in which it is mainly the intrinsic qualities of the person or the product that governs success. But there is another way to look at it, a nondeterministic view. In this view there are many high-quality but unknown books, singers, actors, and what makes one or another come to stand out is largely a conspiracy of random and minor factors—that is, luck. In this view the traditional executives are just spinning their wheels. Thanks to the Internet, this idea has been tested. The researchers who tested it focused on the music market, in which Internet sales are coming to dominate. For their study they recruited 14,341 participants who were asked to listen to, rate, and if they desired, download 48 songs by bands they had not heard of.10 Some of the participants were also allowed to view data on the popularity of each song—that is, on how many fellow participants had downloaded it. These participants were divided into eight separate “worlds” and could see only the data on downloads of people in their own world. All the artists in all the worlds began with zero downloads, after which each world evolved independently. There was also a ninth group of participants, who were not shown any data. The researchers employed the popularity of the songs in this latter group of insulated listeners to define the “intrinsic quality” of each song—that is, its appeal in the absence of external influence. If the deterministic view of the world were true, the same songs ought to have dominated in each of the eight worlds, and the popularity rankings in those worlds ought to have agreed with the intrinsic quality as determined by the isolated individuals. But the researchers found exactly the opposite: the popularity of individual songs varied widely among the different worlds, and different songs of similar intrinsic quality also varied widely in their popularity. For example, a song called “Lockdown” by a band called 52metro ranked twenty-six out of forty-eight in intrinsic quality but was the number-1 song in one world and the number-40 song in another. In this experiment, as one song or another by chance got an early edge in downloads, its seeming popularity influenced future shoppers. It’s a phenomenon that is well-known in the movie industry: moviegoers will report liking a movie more when they hear beforehand how good it is. In this example, small chance influences created a snowball effect and made a huge difference in the future of the song. Again, it’s the butterfly effect.

Yet such misperceived “trends” continue to dominate boardroom discussions as if they were more meaningful than they really are. Mlodinow writes:

One of the most high profile examples of anointment and regicide in modern Hollywood was the case of Sherry Lansing, who ran Paramount with great success for many years. Under Lansing, Paramount won Best Picture awards for Forrest Gump, Braveheart, and Titanic and posted its two highest- grossing years ever. Then Lansing’s reputation suddenly plunged, and she was dumped after Paramount experienced, as Variety put it, “a long stretch of underperformance at the box office.” In mathematical terms there is both a short and a long explanation for Lansing’s fate. First, the short answer. Look at this series of percentages: 11.4, 10.6, 11.3, 7.4, 7.1, 6.7. Notice something? Lansing’s boss, Sumner Redstone, did too, and for him the trend was significant, for those six numbers represented the market share of Paramount’s Motion Picture Group for the final six years of Lansing’s tenure. The trend caused BusinessWeek to speculate that Lansing “may simply no longer have Hollywood’s hot hand.” Soon Lansing announced she was leaving, and a few months later a talent manager named Brad Grey was brought on board. How can a surefire genius lead a company through seven great years and then fail practically overnight? There were plenty of theories explaining Lansing’s early success. While Paramount was doing well, Lansing was praised for making it one of Hollywood’s best- run studios and for her knack for turning conventional stories into $100 million hits. When her fortune changed, the revisionists took over. Her penchant for making successful remakes and sequels became a drawback. Most damning of all, perhaps, was the notion that her failure was due to her “middle-of-the-road tastes.” She was now blamed for green- lighting such box office dogs as Timeline and Lara Croft Tomb Raider: The Cradle of Life. Suddenly the conventional wisdom was that Lansing was risk averse, old- fashioned, and out of touch with the trends. But can she really be blamed for thinking that a Michael Crichton bestseller would be promising movie fodder? And where were all the Lara Croft critics when the first Tomb Raider film took in $131 million in box office revenue? Even if the theories of Lansing’s shortcomings were plausible, consider how abruptly her demise occurred. Did she become risk averse and out of touch overnight? Because Paramount’s market share plunged that suddenly. One year Lansing was flying high; the next she was a punch line for late- night comedians. Her change of fortune might have been understandable if, like others in Hollywood, she had become depressed over a nasty divorce proceeding, had been charged with embezzlement, or had joined a religious cult. That was not the case. And she certainly hadn’t sustained any damage to her cerebral cortex. The only evidence of Lansing’s newly developed failings that her critics could offer was, in fact, her newly developed failings. In hindsight it is clear that Lansing was fired because of the industry’s misunderstanding of randomness and not because of her flawed decision making: Paramount’s films for the following year were already in the pipeline when Lansing left the company. So if we want to know roughly how Lansing would have done in some parallel universe in which she remained in her job, all we need to do is look at the data in the year following her departure. With such films as War of the Worlds and The Longest Yard, Paramount had its best summer in a decade and saw its market share rebound to nearly 10 percent. That isn’t merely ironic— it’s again that aspect of randomness called regression toward the mean. A Variety headline on the subject read, “Parting Gifts: Old Regime’s Pics Fuel Paramount Rebound,” but one can’t help but think that had Viacom (Paramount’s parent company) had more patience, the headline might have read, “Banner Year Puts Paramount and Lansing’s Career Back on Track.” Sherry Lansing had good luck at the beginning and bad luck at the end … [T]he same sort of misjudgments that plague Hollywood also plague people’s perceptions in all realms of life.

Regarding fiction books, Mlodinow writes:

A few years ago The Sunday Times of London conducted an experiment. Its editors submitted typewritten manuscripts of the opening chapters of two novels that had won the Booker Prize—one of the world’s most prestigious and most influential awards for contemporary fiction—to twenty major publishers and agents. One of the novels was In a Free State by V. S. Naipaul, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature; the other was Holiday by Stanley Middleton. One can safely assume that each of the recipients of the manuscripts would have heaped praise on the highly lauded novels had they known what they were reading. But the submissions were made as if they were the work of aspiring authors, and none of the publishers or agents appeared to recognize them. How did the highly successful works fare? All but one of the replies were rejections. The exception was an expression of interest in Middleton’s novel by a London literary agent. The same agent wrote of Naipaul’s book, “We … thought it was quite original. In the end though I’m afraid we just weren’t quite enthusiastic enough to be able to offer to take things further.”

Focus groups can also be very misleading. As Mlodinow writes:

A friend of mine once worked for a start-up computer-games company. She would often relate how, although the marketing director conceded that small focus groups were suited for “qualitative conclusions only,” she nevertheless sometimes reported an “overwhelming” 4-to-2 or 5-to-1 agreement among the members of the group as if it were meaningful. But suppose you hold a focus group in which 6 people will examine and comment on a new product you are developing. Suppose that in actuality the product appeals to half the population. How accurately will this preference be reflected in your focus group? … [T]here are 20 ways in which the group members could split 50/50, accurately reflecting the views of the populace at large. But there are also 1 + 6 + 15 + 15 + 6 + 1 = 44 ways in which you might find an unrepresentative consensus, either for or against. So if you are not careful, the chances of being misled are 44 out of 64, or about two- thirds. This example does not prove that if agreement is achieved, it is random. But neither should you assume that it is significant.

Mlodinow then describes the randomness in the wine and vodka industries to illustrate the random vagaries of taste:

Another subjective measurement that is given more credence than it warrants is the rating of wines. Back in the 1970s the wine business was a sleepy enterprise, growing, but mainly in the sales of low- grade jug wines. Then, in 1978, an event often credited with the rapid growth of that industry occurred: a lawyer turned self- proclaimed wine critic, Robert M. Parker Jr., decided that, in addition to his reviews, he would rate wines numerically on a 100-point scale. Over the years most other wine publications followed suit. Today annual wine sales in the United States exceed $20 billion, and millions of wine aficionados won’t lay their money on the counter without first looking to a wine’s rating to support their choice. So when Wine Spectator awarded, say, the 2004 Valentín Bianchi Argentine cabernet sauvignon a 90 rather than an 89, that single extra point translated into a huge difference in Valentín Bianchi’s sales. In fact, if you look in your local wine shop, you’ll find that the sale and bargain wines, owing to their lesser appeal, are often the wines rated in the high 80s. But what are the chances that the 2004 Valentín Bianchi Argentine cabernet that received a 90 would have received an 89 if the rating process had been repeated, say, an hour later? In his 1890 book The Principles of Psychology, William James suggested that wine expertise could extend to the ability to judge whether a sample of Madeira came from the top or the bottom of a bottle. In the wine tastings that I’ve attended over the years, I’ve noticed that if the bearded fellow to my left mutters “a great nose” (the wine smells good), others certainly might chime in their agreement. But if you make your notes independently and without discussion, you often find that the bearded fellow wrote, “Great nose” the guy with the shaved head scribbled, “No nose” and the blond woman with the perm wrote, “Interesting nose with hints of parsley and freshly tanned leather.” From the theoretical viewpoint, there are many reasons to question the significance of wine ratings. For one thing, taste perception depends on a complex interaction between taste and olfactory stimulation. Strictly speaking, the sense of taste comes from five types of receptor cells on the tongue: salty, sweet, sour, bitter, and umami. The last responds to certain amino acid compounds (prevalent, for example, in soy sauce). But if that were all there was to taste perception, you could mimic everything— your favorite steak, baked potato, and apple pie feast or a nice spaghetti Bolognese— employing only table salt, sugar, vinegar, quinine, and monosodium glutamate. Fortunately there is more to gluttony than that, and that is where the sense of smell comes in. The sense of smell explains why, if you take two identical solutions of sugar water and add to one a (sugar- free) essence of strawberry, it will taste sweeter than the other. The perceived taste of wine arises from the effects of a stew of between 600 and 800 volatile organic compounds on both the tongue and the nose. That’s a problem, given that studies have shown that even flavor-trained professionals can rarely reliably identify more than three or four components in a mixture … Expectations also affect your perception of taste. In 1963 three researchers secretly added a bit of red food color to white wine to give it the blush of a rosé. They then asked a group of experts to rate its sweetness in comparison with the untinted wine. The experts perceived the fake rosé as sweeter than the white, according to their expectation. Another group of researchers gave a group of oenology students two wine samples. Both samples contained the same white wine, but to one was added a tasteless grape anthocyanin dye that made it appear to be red wine. The students also perceived differences between the red and the white corresponding to their expectations. And in a 2008 study a group of volunteers asked to rate five wines rated a bottle labeled $90 higher than another bottle labeled $10, even though the sneaky researchers had filled both bottles with the same wine. What’s more, this test was conducted while the subjects were having their brains imaged in a magnetic resonance scanner. The scans showed that the area of the brain thought to encode our experience of pleasure was truly more active when the subjects drank the wine they believed was more expensive. But before you judge the oenophiles, consider this: when a researcher asked 30 cola drinkers whether they preferred Coke or Pepsi and then asked them to test their preference by tasting both brands side by side, 21 of the 30 reported that the taste test confirmed their choice even though this sneaky researcher had put Coke in the Pepsi bottle and vice versa. When we perform an assessment or measurement, our brains do not rely solely on direct perceptional input. They also integrate other sources of information— such as our expectation … Given all these reasons for skepticism, scientists designed ways to measure wine experts’ taste discrimination directly. One method is to use a wine triangle. It is not a physical triangle but a metaphor: each expert is given three wines, two of which are identical. The mission: to choose the odd sample. In a 1990 study, the experts identified the odd sample only two- thirds of the time, which means that in 1 out of 3 taste challenges these wine gurus couldn’t distinguish a pinot noir with, say, “an exuberant nose of wild strawberry, luscious blackberry, and raspberry,” from one with “the scent of distinctive dried plums, yellow cherries, and silky cassis.” In the same study an ensemble of experts was asked to rank a series of wines based on 12 components, such as alcohol content, the presence of tannins, sweetness, and fruitiness. The experts disagreed significantly on 9 of the 12 components. Finally, when asked to match wines with the descriptions provided by other experts, the subjects were correct only 70 percent of the time. Wine critics are conscious of all these difficulties. “On many levels … [the ratings system] is nonsensical,” says the editor of Wine and Spirits Magazine. And according to a former editor of Wine Enthusiast, “The deeper you get into this the more you realize how misguided and misleading this all is.” Yet the rating system thrives. Why? The critics found that when they attempted to encapsulate wine quality with a system of stars or simple verbal descriptors such as good, bad, and maybe ugly, their opinions were unconvincing. But when they used numbers, shoppers worshipped their pronouncements. Numerical ratings, though dubious, make buyers confident that they can pick the golden needle (or the silver one, depending on their budget) from the haystack of wine varieties, makers, and vintages. The wine might be rated 91, but that number is meaningless if we have no estimate of the variation that would occur if the identical wine were rated again and again or by someone else. It might help to know, for instance, that a few years back, when both The Penguin Good Australian Wine Guide and On Wine’s Australian Wine Annual reviewed the 1999 vintage of the Mitchelton Blackwood Park Riesling, the Penguin guide gave the wine five stars out of five and named it Penguin Best Wine of the Year, while On Wine rated it at the bottom of all the wines it reviewed, deeming it the worst vintage produced in a decade.

And regarding vodka, Mlodinow writes:

Marketers also know this and design ad campaigns to create and then exploit our expectations. One arena in which that was done very effectively is the vodka market. Vodka is a neutral spirit, distilled, according to the U.S. government definition, “as to be without distinctive character, aroma, taste or color.” Most American vodkas originate, therefore, not with passionate, flannel-shirted men like those who create wines, but with corporate giants like the agrochemical supplier Archer Daniels Midland. And the job of the vodka distiller is not to nurture an aging process that imparts finely nuanced flavor but to take the 190-proof industrial swill such suppliers provide, add water, and subtract as much of the taste as possible. Through massive image-building campaigns, however, vodka producers have managed to create very strong expectations of difference. As a result, people believe that this liquor, which by its very definition is without a distinctive character, actually varies greatly from brand to brand. Moreover, they are willing to pay large amounts of money based on those differences. Lest I be dismissed as a tasteless boor, I wish to point out that there is a way to test my ravings. You could line up a series of vodkas and a series of vodka sophisticates and perform a blind tasting. As it happens, The New York Times did just that. And without their labels, fancy vodkas like Grey Goose and Ketel One didn’t fare so well. Compared with conventional wisdom, in fact, the results appeared random. Moreover, of the twenty-one vodkas tasted, it was the cheap bar brand, Smirnoff, that came out at the top of the list. Our assessment of the world would be quite different if all our judgments could be insulated from expectation and based only on relevant data.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll explore the randomness of bureaucracies, graders, and others, and how to live with them.