Randomness – Part 2

Randomness and contentment.

In this essay, we’ll further explore the role of randomness in people’s financial success and how that understanding should make us more, rather than less, content, using Nassim Taleb’s Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of Chance in Life and Markets, and Leonard Mlodinow’s The Drunkard’s Walk: How Randomness Rules Our Lives.

As Taleb writes:

[W]e often have the mistaken impression that a strategy is an excellent strategy, or an entrepreneur a person endowed with “vision,” or a trader a talented trader, only to realize that 99.9% of their past performance is attributable to chance, and chance alone. Ask a profitable investor to explain the reasons for his success; he will offer some deep and convincing interpretation of the results. Frequently, these delusions are intentional and deserve to bear the name “charlatanism.” …. Recall that the survivorship bias depends on the size of the initial population. The information that a person derived some profits in the past, just by itself, is neither meaningful nor relevant. We need to know the size of the population from which he came. In other words, without knowing how many managers out there have tried and failed, we will not be able to assess the validity of the track record. If the initial population includes ten managers, then I would give the performer half my savings without a blink. If the initial population is composed of 10,000 managers, I would ignore the results. The latter situation is generally the case; these days so many people have been drawn to the financial markets. Many college graduates are trading as a first career, failing, then going to dental school.

Recalling the previous essay in this series, Taleb’s point is that some managers will tend to have good track records as a result of mere chance, especially when the initial pool of managers is large. Taleb therefore places little to no value in the track records of managers, and much more value in how they think when they make trades. As Taleb writes, “If, as in a fairy tale, these fictional managers materialized into real human beings, one of these could be the person I am meeting tomorrow at 11:45 a.m. Why did I select 11:45 a.m.? Because I will question him about his trading style. I need to know how he trades. I will then be able to claim that I have to rush to a lunch appointment if the manager puts too much emphasis on his track record.”

As Mlodinow writes, we have a tendency to over-value track records because of an asymmetry in information:

In any complex string of events in which each event unfolds with some element of uncertainty, there is a fundamental asymmetry between past and future. Imagine, for example, a dye molecule floating in a glass of water. The molecule will … follow a drunkard’s walk. But even that aimless movement makes progress in some direction. If you wait three hours, for example, the molecule will typically have traveled about an inch from where it started. Suppose that at some point the molecule moves to a position of significance and so finally attracts our attention … [W]e might look for the reason why that unexpected event occurred. Now suppose we dig into the molecule’s past. Suppose, in fact, we trace the record of all its collisions. We will indeed discover how first this bump from a water molecule and then that one propelled the dye molecule on its zigzag path from there to here. In hindsight, in other words, we can clearly explain why the past of the dye molecule developed as it did. But the water contains many other water molecules that could have been the ones that interacted with the dye molecule. To predict the dye molecule’s path beforehand would have therefore required us to calculate the paths and mutual interactions of all those potentially important water molecules. That would have involved an almost unimaginable number of mathematical calculations, far greater in scope and difficulty than the list of collisions needed to understand the past. In other words, the movement of the dye molecule was virtually impossible to predict before the fact even though it was relatively easy to understand afterward. That fundamental asymmetry is why in day-to-day life the past often seems obvious even when we could not have predicted it.

Mlodinow points out that:

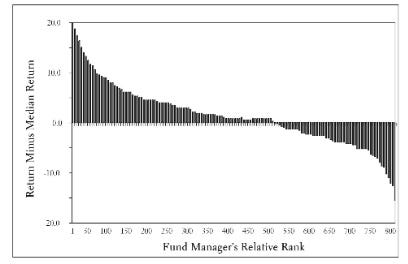

The same thing is true of the stock market. Consider, for instance, the performance of mutual funds … [I]t is common, when choosing a mutual fund, to look at past performance. Indeed, it is easy to find nice, orderly patterns when looking back. Here, for example, is a graph of the performance of 800 mutual fund managers over the five-year period, 1991–1995. Performance versus ranking of the top mutual funds in the five-year period 1991–1995. On the vertical axis are plotted the funds’ gains or losses relative to the average fund of the group. In other words, a return of 0 percent means the fund’s performance was average for this five-year period. On the horizontal axis is plotted the managers’ relative rank, from the number-1 performer to the number-800 performer. To look up the performance of, say, the 100th most successful mutual fund manager in the given five-year period, you find the point on the graph corresponding to the spot labeled 100 on the horizontal axis.

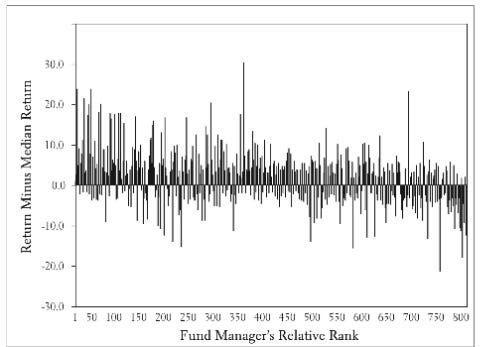

Any analyst, no doubt, could give a number of convincing reasons why the top managers represented here succeeded, why the bottom ones failed, and why the curve should take this shape. And whether or not we take the time to follow such analyses in detail, few are the investors who would choose a fund that has performed 10 percent below average in the past five years over a fund that has done 10 percent better than average. It is easy, looking at the past, to construct such nice graphs and neat explanations, but this logical picture of events is just an illusion of hindsight with little relevance for predicting future events. In the graph on chapter 10, for example, I compare how the same funds, still ranked in order of their performance in the initial five-year period, performed in the next five-year period. In other words, I maintain the ranking based on the period 1991–1995, but display the return the funds achieved in 1996–2000. If the past were a good indication of the future, the funds I considered in the period 1991–1995 would have had more or less the same relative performance in 1996–2000. That is, if the winners (at the left of the graph) continued to do better than the others, and the losers (at the right) worse, this graph should be nearly identical to the last. Instead, as we can see, the order of the past dissolves when extrapolated to the future, and the graph ends up looking like random noise.

Mlodinow concludes that “we place too much confidence in the overly precise predictions of people—political pundits, financial experts, business consultants—who claim a track record demonstrating expertise.” Mlodinow points out that good historians know better:

Historians, whose profession is to study the past, are as wary as scientists of the idea that events unfold in a manner that can be predicted. In fact, in the study of history the illusion of inevitability has such serious consequences that it is one of the few things that both conservative and socialist historians can agree on. The socialist historian Richard Henry Tawney, for example, put it like this: “Historians give an appearance of inevitability … by dragging into prominence the forces which have triumphed and thrusting into the background those which they have swallowed up.” And the historian Roberta Wohlstetter, who received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from Ronald Reagan, said it this way: “After the event, of course, a signal is always crystal clear; we can now see what disaster it was signaling … But before the event it is obscure and pregnant with conflicting meanings.”

Still, the financial press is beholden to an army of “financial gurus.” As Mlodinow writes:

There is much evidence, for instance, that the performance of stocks is random—or so close to being random that in the absence of insider information and in the presence of a cost to make trades or manage your portfolio, you can’t profit from any deviations from randomness. Nevertheless, Wall Street has a long tradition of guru analysts, and the average analyst’s salary, at the end of the 1990s, was about $3 million. How do those analysts do? According to a 1995 study, the eight to twelve most highly paid “Wall Street superstars” invited by Barron’s to make market recommendations at its annual roundtable merely matched the average market return. Studies in 1987 and 1997 found that stocks recommended by the prognosticators on the television show Wall Street Week did much worse, lagging far behind the market. And in a study of 153 newsletters, a researcher at the Harvard Institute of Economic Research found “no significant evidence of stock-picking ability.” By chance alone, some analysts and mutual funds will always exhibit impressive patterns of success. And though many studies show that these past market successes are not good indicators of future success—that is, that the successes were largely just luck—most people feel that the recommendations of their stockbrokers or the expertise of those running mutual funds are worth paying for. Many people, even intelligent investors, therefore buy funds that charge exorbitant management fees. In fact, when a group of savvy students from the Wharton business school were given a hypothetical $10,000 and prospectuses describing four index funds, each composed in order to mirror the S&P 500, the students overwhelmingly failed to choose the funds with the lowest fees. Since paying even an extra 1 percent per year in fees could, over the years, diminish your retirement fund by as much as one-third or even one-half, the savvy students didn’t exhibit very savvy behavior.

Coming to really understand the role of randomness in life should free people of many of the misconceptions that may be making them unhappy. To illustrate, Taleb tells a story of two people who are composites of people he’s known over the years:

Marc lives on Park Avenue in New York City with his wife, Janet, and their three children. He makes $500,000 a year … Janet’s immediate acquaintance is composed of the other parents of the Manhattan private school attended by their children, and their neighbors at the co-operative apartment building where they live. From a materialistic standpoint, they come at the low end of such a set, perhaps even at the exact bottom. They would be the poorest of these circles, as their co- op is inhabited by extremely successful corporate executives, Wall Street traders, and high- flying entrepreneurs. Their children’s private school harbors the second set of children of corporate raiders, from their trophy wives— perhaps even the third set, if one takes into account the age discrepancy and the model- like features of the other mothers. By comparison, Marc’s wife, Janet, like him, presents a homely country-home-with-a-rose-garden type of appearance. Marc’s strategy of staying in Manhattan may be rational, as his demanding work hours would make it impossible for him to commute. But the costs on his wife, Janet, are monstrous. Why? Because of their relative nonsuccess— as geographically defined by their Park Avenue neighborhood. Every month or so, Janet has a crisis, giving in to the strains and humiliations of being snubbed by some other mother at the school where she picks up the children, or another woman with larger diamonds by the elevator of the co-op where they live in the smallest type of apartments (the G line). Why isn’t her husband so successful? Isn’t he smart and hardworking? Didn’t he get close to 1600 on the SAT? Why is this Ronald Something, whose wife never even nods to Janet, worth hundreds of millions, when her husband went to Harvard and Yale and has such a high IQ and has hardly any substantial savings? We will not get too involved in the Chekhovian dilemmas in the private lives of Marc and Janet, but their case provides a very common illustration of the emotional effect of survivorship bias. Janet feels that her husband is a failure, by comparison, but she is miscomputing the probabilities in a gross manner— she is using the wrong distribution to derive a rank. As compared to the general U.S. population, Marc has done very well, better than 99.5% of his compatriots. As compared to his high school friends, he did extremely well, a fact that he could have verified had he had time to attend the periodic reunions, and he would come at the top. As compared to the other people at Harvard, he did better than 90% of them (financially, of course). As compared to his law school comrades at Yale, he did better than 60% of them. But as compared to his co-op neighbors, he is at the bottom! Why? Because he chose to live among the people who have been successful, in an area that excludes failure. In other words, those who have failed do not show up in the sample, thus making him look as if he were not doing well at all. By living on Park Avenue, one does not have exposure to the losers, one only sees the winners. As we are cut to live in very small communities, it is difficult to assess our situation outside of the narrowly defined geographic confines of our habitat. In the case of Marc and Janet, this leads to considerable emotional distress; here we have a woman who married an extremely successful man but all she can see is comparative failure, for she cannot emotionally compare him to a sample that would do him justice.

As explored in a previous essay series on happiness, a fixation on “status” can make people very unhappy. In addition, as Taleb writes:

Aside from the misperception of one’s performance, there is a social treadmill effect: You get rich, move to rich neighborhoods, then become poor again. To that add the psychological treadmill effect; you get used to wealth and revert to a set point of satisfaction. This problem of some people never really getting to feel satisfied by wealth (beyond a given point) has been the subject of technical discussions on happiness … Someone would rationally say to Janet: “Go read this book Fooled by Randomness by one mathematical trader on the deformations of chance in life; it would give you a statistical sense of perspective and would accordingly make you feel better.” … [But] becoming more rational, or not feeling emotions of social slights, is not part of the human race, at least not with our current biology.

Much better, recommends Taleb, is following a strategy of “satisficing”:

[O]ur brains would not be able to operate without … shortcuts. The first thinker who figured it out was Herbert Simon, an interesting fellow in intellectual history. He started out as a political scientist (but he was a formal thinker, not the literary variety of political scientists who write about Afghanistan in Foreign Affairs); he was an artificial-intelligence pioneer, taught computer science and psychology, did research in cognitive science, philosophy, and applied mathematics, and received the Bank of Sweden Prize for Economics in honor of Alfred Nobel. His idea is that if we were to optimize at every step in life, then it would cost us an infinite amount of time and energy. Accordingly, there has to be in us an approximation process that stops somewhere. Clearly he got his intuitions from computer science— he spent his entire career at Carnegie- Mellon University in Pittsburgh, which has a reputation as a computer science center. “Satisficing” was his idea (the melding together of satisfy and suffice): You stop when you get a near-satisfactory solution. Otherwise it may take you an eternity to reach the smallest conclusion or perform the smallest act. We are therefore rational, but in a limited way: “boundedly rational.” He believed that our brains were a large optimizing machine that had built-in rules to stop somewhere.

Unless, of course, a fixation on winning an ever-elusive status race gets in the way of that logic:

We know that people of a happy disposition tend to be of the satisficing kind, with a set idea of what they want in life and an ability to stop upon gaining satisfaction. Their goals and desires do not move along with the experiences. They do not tend to experience the internal treadmill effects of constantly trying to improve on their consumption of goods by seeking higher and higher levels of sophistication. In other words, they are neither avaricious nor insatiable … [Y]ou can decide whether to be (relatively) poor, but free of your time, or rich but as dependent as a slave … [R]esearch on happiness shows that those who live under a self-imposed pressure to be optimal in their enjoyment of things suffer a measure of distress.

Opting out of a status race gives one a lot more free time. As Taleb writes:

It took me a while to figure out that we are not designed for schedules. The realization came when I recognized the difference between writing a paper and writing a book. Books are fun to write, papers are painful. I tend to find the activity of writing greatly entertaining, given that I do it without any external constraint. You write, and may interrupt your activity, even in mid-sentence, the second it stops being attractive. After the success of this book, I was asked to write papers by the editors of a variety of professional and scientific journals. Then they asked me how long the piece should be. What? How long? For the first time in my life, I experienced a loss of pleasure in writing! Then I figured out a personal rule: For writing to be agreeable to me, the length of the piece needs to remain unpredictable. If I see the end of it, or if I am subjected to the shadow of an outline, I give up. I repeat that our ancestors were not subjected to outlines, schedules, and administrative deadlines.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll explore how human biases can obscure the reality of career randomness.