Public Sector Unions – Part 6

The massive, hidden fiscal liabilities public sector unions place on taxpayers.

As we continue our discussion of the many dysfunctions caused by public sector unions, this essay will focus on their demands regarding the use of taxpayer money. As Professor Clyde Summers has explained, when it comes to public sector unions, “The collective agreement is not a private decision, but a governmental decision; it is not so much a contract as a legislative act. Labor costs may be seventy percent of a city’s budget. Bargaining on wages and other economic items, therefore, inevitably involves the level of taxes and the level of services.”

As Philip Howard writes in his book Not Accountable: Rethinking the Constitutionality of Public Employee Unions:

Unions not only impose rules but also view their role as negotiating any supervisory decision that is in any way discretionary. “Virtually any idea for saving money through outsourcing or consolidation of services,” as E. J. McMahon and Terry O’Neil describe in their essay “Taylor Made,” “must first be negotiated and agreed to by the union representing the employees who currently provide the service.” “‘Mere monetary savings,’” under rulings from New York’s Public Employment Relations Board, are “‘insufficient’ to overcome an employer’s obligation to fully bargain the topic.”

These excessive expenditures of taxpayer funds are hidden beneath layers of accounting terms designed to obscure them from public understanding.

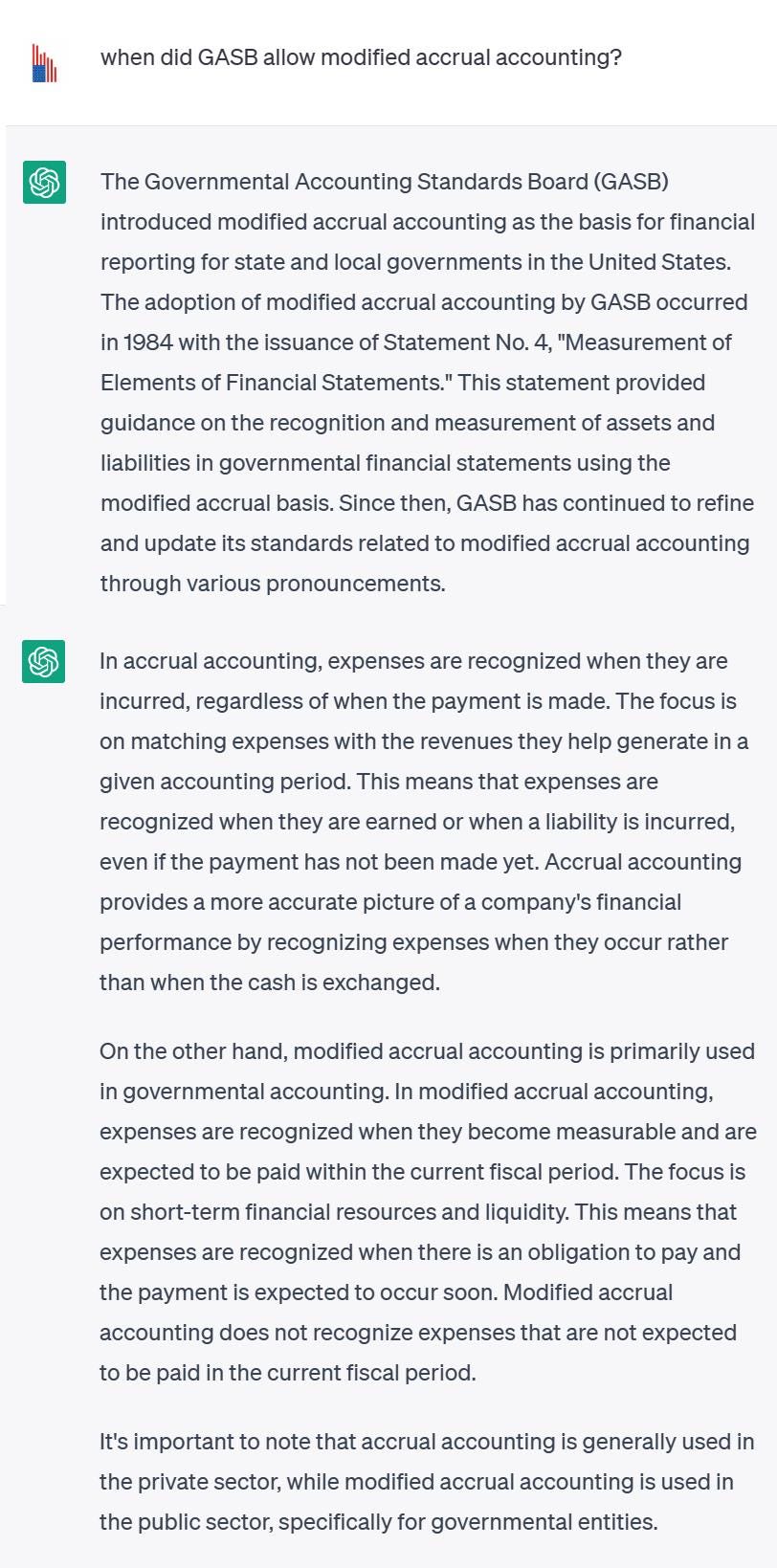

One informed reader of this Substack encouraged me to look more closely into how governments came to be able to hide these huge unfunded liabilities from public view, and he directed me to the Government Accounting Standards Board (GASB) decision in 1984 to allow state and local government to depart from the strict accouting standards required of the private sector, and to instead adopt what’s called “modified accrual” accounting. I turned to ChatGPT for some clarification, and was told the following:

Modified accrual accounting allows governments to hide the unfunded liabilities they give away to public sector unions, leaving taxpayers with large surprise bills today, and even larger surprise bills in the future. Indeed, simple “cost of living adjustments” (COLAs) embedded in public sector pension plans add even greater hidden costs to these unfunded liabilities. As my informed reader explains:

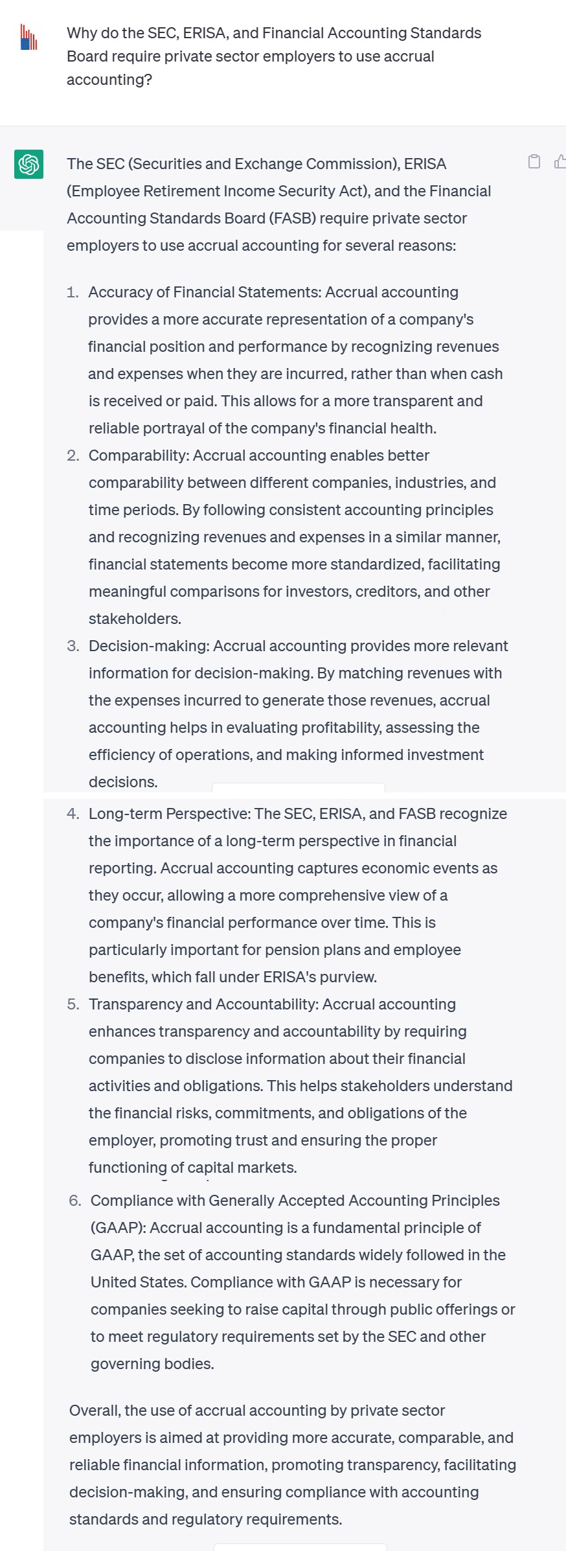

[A] cost of living adjustment “continues forever as an increase in recurring base expense. Moreover, a current COLA adjustment -- say 1% each year for the next 3 years -- results in a permanent increase in the basis for all future pension benefits for the individuals not yet retired … That adjustment wasn't envision 20 or 25 years ago, so there were never any funding amounts contributed way back when to make up what would be required in contributions to “make whole” the pension asset base. As the result, for this group of tenured 20-25 year employees -- who will be receiving future benefits which include the 3% increase -- those associated “expenses” will necessarily impact current and future budgets after they have retired -- even though they are no longer employed or contributing to the current workload. In other words, those future taxpayers and future budgets will be absorbing these incremental additional expenses which are associated with work of employees from 20-25 years ago … This is a fundamental violation of the accounting principle of “matching expenses with revenues” in which such expenses and revenues are matched to the period in which the underlying activity actually occurred. This is a fundamental principle of accrual accounting, which is required of all private sector employers by the Securities and Exchange Commission, the federal ERISA law, and the Financial Accounting Standards Board.

And here’s what ChatGPT says about the importance of accrual accounting (from which state and local government are exempt):

Interestingly, in 1937 (the same year President Franklin Delano Roosevelt stated his opposition to public sector unions), the state of California passed a law known as the “City Employees Retirement Law, which took a much different (and responsible) approach to the means of paying for government pensions, requiring a balancing of money-in compared to money-obligated-out by the system, with any difference taken out of other funds available in the government treasury. Sections 102 and 103 of the California statute stated:

SEC. 102. Contributions made to the retirement system under this article shall be applied by the board of retirement to meet the county's obligations under the system in the order and amounts as follows: First, in an amount equal during each fiscal year to the liability accruing on the county because of service rendered during such year and on account of pensions provided for in section 115 and sections 135 and 136, such amount to be determined by the actuarial valuation provided for in Article 3, as interpreted by the actuary; second, in an amount equal during each fiscal year to the payments made, from contributions by the county during such year as provided in Article 10; third, the balance of such contributions, on the liabilities accrued on account of prior service benefits granted under sections 116 and 135.

SEC. 103. The duty hereby imposed on the board of supervisors to make such appropriations and transfers is hereby declared to be mandatory, and if it should fail or neglect to make such appropriations or transfers, it is the duty of the county auditor to transfer from any moneys available in any fund in the county treasury the sums herein specified, despite the failure or neglect of the board of supervisors, with the same force and effect as though made by action of said board.

That statute, sadly, was subsequently amended to allow local governments to take on huge pension liabilities without having to fund them at the same time.

As my informed reader points out, much of the reason we find ourselves in the public sector union pension mess relates to the backgrounds of those who compose the legislative bodies at the state and local level who allow these unfunded pension liabilities. As he writes, “The incidence of members, both appointed and elected, is very likely to be something on the order of 70% who (and/or their spouses) hail directly from current or former public sector careers (including teachers, regulators, agency staff, etc.) or are otherwise highly beholden to various public sector funding sources (such as [various ‘public interest groups’) either for board seats, grants, contracts, tax exemptions, [etc.] ... Further compounding the challenge of encouraging, developing and promoting [more] ‘civically oriented citizens’ to serve on such appointed or elected positions is the presence of [disclosure regimes like California's] Form 700 (Conflict of Interest Financial Disclosure) which places a giant spotlight on private sector applicants sources of income, amount of income by employer, disclosure of major clients representing more than 10% of annual revenues, separate detailed disclosure of all investment holdings -- both stocks and real estate. Meanwhile, candidates from public sector employment are exempt from all disclosure details pertaining to jobs, employers, compensation and benefits received. In addition, these candidates are also categorically exempted from reporting of the [present value] of Pension Funds held in their name and OPEB Programs in their favor or any disclosure concerning the funding status of such "assets" held in their name. The only solution is to establish independent citizens' review committees -- chaired by and containing a preponderance of members from private sector employment (private, not including non-profits) and preferably with candidates who are familiar with signing the front of paychecks ... [We need to] start speaking directly to the people about how these problems came to be, including detailed disclosures about the magnitude and generosity of the unfunded promises made to former employees and retirees that serve as a drag on today's generation of unsuspecting taxpayers, and which have resulted directly in underfunding of school infrastructure, roadways, libraries, parks and other such public amenities.”

As Howard explains:

Public pay should be transparent to taxpayers, however, and not prone to abuse. Instead, public unions have negotiated contracts that encourage manipulation and fiscally irresponsible practices. Elected officials have been complicit—to attract union political support today, politicians agreed to long-term pension and health benefits without a plan to fund them. Instead of paying into the system as obligations were incurred, many states, under pressure from public unions, kicked the can down the road so as not to cut current services. As the deficit reached scandalous proportions in recent years, states started moderating the benefits for new hires but did little to relieve many states and municipalities from the fiscal vise. Unfunded benefit liabilities made up 40 percent of the $18 billion in debt that forced the city of Detroit to declare bankruptcy in 2013. In 2012, Mayor Michael Bloomberg claimed that “every penny” of personal income tax collected by New York City went straight to pension payments. A 2021 Moody’s report found that Illinois’s state pension liability (not even including municipal pensions) was so high that every household in the state would need to pay $65,000 to cover the difference. How to cure these deficits is unclear. The states with the largest deficits are already losing population because of high taxes and aging demographics. A study by the Urban Institute found that new state employees in New Jersey had to pay more into the pension plan than they would ever get back—unwittingly subsidizing older retirees. Some observers have suggested that bankruptcy, not currently allowed for states, is the only realistic solution for Illinois and certain other states. The pressure to cut current services is enormous. Des Moines cut library hours and reduced street cleaning to make up for pension-driven budget shortfalls. Rockford, Illinois, may soon sell its municipal water system. Pasadena cut over 120 local jobs, including numerous police positions, and reduced transit service after facing insurmountable pension liabilities. Oakland in 2010 laid off eighty police officers, during a crime wave, in order to fund retirement obligations. Clawing our way out of these public deficits requires doing everything possible to deliver government more efficiently. Instead, public unions not only shackle public executives with inefficient work rules, as discussed above, but have designed a public compensation system that is unsustainable. The bottom line is that taxpayers are on the hook for pension and health-care obligations far greater than in the private sector. The fact that these benefits are largely hidden from public view does not reflect well on the motives of unions and their political enablers. As political scientists Sarah Anzia and Terry Moe explain, “Health and pension benefits are extremely complicated, difficult for the public to understand, difficult for the media to convey—and thus nearly invisible politically.” Public employee unions have focused their demands on this “electoral blind spot,” with the cooperation of elected officials who will be out of office when the bill comes due. Unions then protect themselves against the inevitable fiscal downfall by getting statutory and constitutional protection against future impairment. The playbook, as described by economist Jeffrey Dorman, resembles a criminal scheme, not business as usual: “The basic process by which states get in such severe financial trouble is well-established. Unions get protection from any future diminishing of pension obligations enshrined into state law or, ideally, the state constitution. Then public sector unions give state politicians big campaign contributions in exchange for large, fiscally irresponsible future pension benefits. The state legislature then underfunds those pensions, keeping the taxpayers from realizing the full cost of the promised pensions and eliminating the near term pain from the pension promises. Unions don’t object to the underfunding because they know the law protects their pensions no matter how bad the situation gets. Eventually, you are Illinois, with a pension shorfall equal to roughly eighteen months of total state spending.” … The accounting rules for public obligations have now changed, so that long-term obligations can no longer be completely hidden from the public. But the horse has left the barn, and there’s still little transparency on how the obligations pile up … By 2012, when government accounting rules were finally aligned with the better practices in the private sector, the retiree deficit hole in New Jersey was too deep to see any way out. An independent commission concluded in 2015 that fully funding its benefit liabilities was “no longer within the State’s means … not only because of the dollar amount of funding required, but also because a State budget so burdened by employee benefits would not be able to weather a recession or permit the State to do what is necessary to promote the general welfare of its citizens.” Five years after the report was published, the reserves needed to pay these obligations had declined further … In a 2013 paper, Professor Thom Reilly showed that public sector employees could expect to collect almost twice as much in postretirement benefits as their private sector counterparts, and over 50 percent more in lifetime average compensation when retirement benefits are factored in. A 2012 study similarly found that “employees of all levels of government generally have substantially more pension wealth than their private sector counterparts.” … [I]n 1988, when the teachers’ union in California promoted a referendum requiring that 40 percent of the total California state general fund be spent on education. In fact, most of the increase in school funding went to increasing teachers’ salaries, without meaningful improvement in school quality. California’s teachers are now among the highest paid in the country, while the performance of California’s schools is in the bottom quartile.

Since then, as Mark Zupan writes in his book Inside Job: How Government Insiders Subvert the Public Interest:

Democratic Governor Jerry Brown of California successfully promoted a $6 billion tax increase to voters in 2012 arguing that half of the associated revenues would be devoted to public schools. In 2014, Governor Brown signed legislation requiring school districts to increase the funds allocated to teachers’ pensions by $3 billion annually within five years. This guaranteed that the proceeds from the 2012 tax increase would primarily reduce the extent to which teachers’ pensions were underfunded rather than improve public school performance.

As Investopedia states, “For some years now, traditional pension plans, also known as pension funds, have been gradually disappearing from the private sector. Today, public sector employees, such as government workers, are the largest group with active and growing pension funds … [T]he Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) of 1974 … aimed to put pensions on a more solid financial footing … ERISA does not cover public pension funds, which instead follow the rules established by state governments …” And whereas private pension funds are paid for by private employees and private employers, “In most states, taxpayers are responsible for picking up the bill if a public employee plan is unable to meet its obligations.”

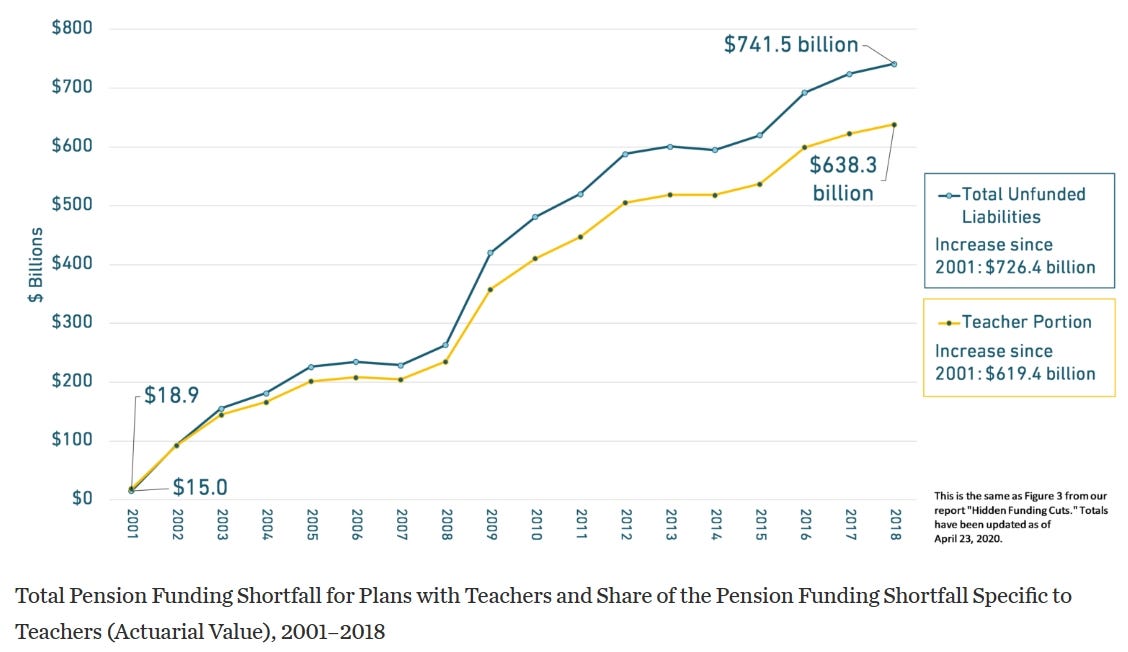

As Zupan described the big picture: “The magnitude of the costs associated with public-sector unionization below the federal level in the United States is staggering. Economists Robert Novy-Marx and Joshua Rauh estimate the unfunded pension liabilities for state and local public employees total $4 trillion. Add to that figure over $1 trillion in unfunded health-care benefits which local and state public workers have been promised and you end up with a fiscal problem of epic proportion.”

Most politicians who support public sector union demands today know they won’t be around to be held accountable when the bill ultimately comes due, so the bill just keeps growing in the meantime. As Howard writes, “Most of the huge debt for public employee benefits in the future, incurred largely as a result of union demands, will not come due during the tenure of the political leaders who acceded to it, nor indeed to the voters at that time. Our children must pay the bill.” And as Howard explains, when some voters come to understand this and propose initiatives to help solve the problem, public sector unions use their large chests of dues money to fend off reforms:

Public employee unions usually lead the charge against taxpayer initiatives to limit spending and taxes. In 2009, Daniel DiSalvo reports, “both Washington State and Maine had spending caps on the ballot. In both cases the public sector unions provided between one-third and one-half of the total funding opposing the measures.” In 2005 public employee unions led a $28 million effort to defeat a spending cap bill in California. In 1991, the New Jersey teachers unions went to war against Democrats when Governor Jim Florio used part of the budget for tax relief instead of schools … Public unions press for long-term budgetary commitments even when, as with retiree benefits, there is no public debate and no reasonable prospect that taxpayers can afford them. The unions also block layoffs and other economizing measures to make up the shortfall. But unions have a plan, as noted, for when the day of reckoning comes: Public unions in Illinois are leading a referendum initiative for a constitutional amendment that would give priority to bargaining agreements over any state law.

And where voters remain ignorant of these problems, municipal government gamble behind the scenes. As Mark Zupan writes in his book Inside Job: How Government Insiders Subvert the Public Interest:

As their membership and influence have grown, so have the benefits that public-sector unions at the state and local levels bestow on their members at the expense of the general public … Every 10 percent increase in a state’s public union membership increases per capita pension liabilities by $1,412, that is, an amount equal to 20 percent of the average state’s per capita GDP … Many state and local governments, aware of the problem whose magnitude the public has yet to grasp, have succumbed to the temptation to take higher risks to avoid disaster. For example, in an effort to make up for the deficit, Illinois has placed 75 percent of its pension portfolio in stocks and other risky assets. Given that the average age of public employees participating in the Illinois retirement system is sixty-two, the typical and prudent approach would involve an allocation of no more than 40 percent of the portfolio to risky assets. Other states similarly have been doubling down and going against basic risk management principles in an effort to reduce their unfunded pension liabilities. The average public plan in the United States places 72 percent of its investments in risky assets. California matches Illinois at 75 percent; New York is at 72 percent; Texas 81 percent; Pennsylvania 82 percent; and New Mexico 85 percent.

Even the Supreme Court has taken note of these developments. As Howard writes:

The corrosive effect of organized union political activity was highlighted in the 2018 Janus case, where the Supreme Court declared unconstitutional an Illinois state statute that required public employees who were not union members to contribute agency fees … The Court’s opinion … describes social damage resulting from the growth of public union power.

As the Supreme Court opinion in the Janus case states:

This ascendance of public-sector unions has been marked by a parallel increase in public spending … Not all that increase can be attributed to public-sector unions, of course, but the mounting costs of public-employee wages, benefits, and pensions undoubtedly played a substantial role. We are told, for example, that Illinois’ pension funds are underfunded by $129 billion as a result of generous public-employee retirement packages. Unsustainable collective bargaining agreements have also been blamed for multiple municipal bankruptcies.

As Zupan writes:

According to a Harvard Business School report on US competitiveness, out of the federal government’s $23.7 trillion in on-balance sheet liabilities as of the 2012 fiscal year, pension and health-care obligations associated with federal workers account for a third of the total. Of the $7.8 trillion in liabilities associated with federal employee benefits, over 80 percent are unfunded. The annual payments made in connection with such promised benefits are primarily underwritten by contributions from various agencies and by the federal government’s general fund receipts generated by taxes and borrowing. The magnitude of the outstanding obligations for federal employee benefits has been growing steadily … Few agencies have begun setting aside funds for retiree benefits. One exception is the United States Postal Service (USPS). As of 2007, Congress has required the USPS to switch from a pay-as-you-go system to a system of setting aside funds for retiree health benefits. The requirement was designed to achieve full funding for projected health benefits within a decade from the then-uncovered amount of $45 billion. The plan was to remove the risk to taxpayers that they would end up paying the bill. The problem is that, due to declining mail volume and its effect on revenues coupled with lobbying by unions representing postal workers (over 85 percent of whom belong to unions), the $5.5 billion mandated annual set-aside payment for future health benefits was reduced to $1.4 billion in 2009. Since 2011, the USPS has been allowed to default fully on the mandated annual payments for future health benefits. Along the way, USPS has racked up $51.7 billion in losses over 2007–2014 and reached its statutory borrowing limit of $15 billion with the US Treasury. Meanwhile, total unfunded pension and health-care liabilities for USPS retirees have grown by 62 percent since 2007 to over $100 billion in 2014. The USPS’s fiscal viability has not been helped by the contract which was negotiated in 2011 with the 205,000-member American Postal Workers Union. The contract included a 3.5 percent pay raise phased in over three years, an automatic annual cost of living wage hike after 2012, and an expansion of no-layoff protections (for example, lower-cost, part-time employees must be terminated prior to any full-time workers). The negotiated provisions fail to relieve the USPS’s fiscal challenges since 80 percent of its expenses involve labor. Postal workers’ wages are now 20–25 percent above comparable private-sector levels, and their total compensation is 30–40 percent higher. The incentives for an entrenched workforce are evidenced by the historical annual quit rate, which is less than 1.5 percent and well below the level at private firms.

To add insult to societal injury, researchers have found that not only do the teachers pension programs insisted on by unions create huge unfunded liabilities for taxpayers, but they don’t even work to the benefit of most teachers:

Teacher pension systems are not only expensive; their structures are inequitable and misguided. Roughly 75% of teachers will be net losers from their pension plan because they will quit or change school districts before they have reached the minimum years of service to be eligible to receive a pension; or they will retire or leave the system before their contributions and the interest earned on them are more than the pension for which they then qualify. Even the winners in this pension lottery—the roughly 25% of teachers who remain on the job in the same system long enough to earn substantial retirement benefits—will have traded years of lower salaries in exchange for disproportionately large retirement benefits.

Politically, Zupan writes, “The hard choices needed to solve this problem are not easily made. Rising public-sector unionization has the clout and the numbers; nearly one in six US employees now work for state and local government, and with their family members and friends comprise a potent voting bloc against ceding gains made over the years.”

It takes rare political courage to embark on a program of any substantial public sector union reform. As Howard writes of Wisconsin’s recent experience:

In 2011, Wisconsin governor Scott Walker proposed a “budget repair bill” that required public employees to contribute to pension and health plans (reducing take-home pay by 8 percent), limited collective bargaining to wages (no more work rules, seniority, and other controls), and required public unions to be authorized by their members each year. The unions went to war against Walker. They organized a massive demonstration of an estimated 100,000 people and physically occupied the state capitol. Protests of thousands of union employees were organized by unions in capitals across the country. To prevent a vote on the law, fourteen Democratic state senators left the state for several weeks to prevent a quorum. The proposed law did not apply to police or firefighters, but the threat of disruption and civil disobedience prompted Walker to put the National Guard on alert and to organize supervisors to perform essential services if public employees went on strike. Walker stood his ground and secured passage of the law. The unions immediately sued and got a ruling declaring the new law invalid as violating state open-meeting laws. But the Wisconsin Supreme Court reversed. The unions then organized a recall petition to remove Walker from office and marshaled $18 million to get Walker removed. After another bloody campaign, Walker prevailed. The Milwaukee County district attorney, a Democrat, then commenced a criminal investigation on whether Walker had illegally coordinated with conservative groups engaged in issue advocacy in the recall election. This too went to the Wisconsin Supreme Court, which in 2015 held that “the special prosecutor’s legal theory is unsupported in either reason or law.” Walker won. Once they lost their collective bargaining powers, the unions became a shadow of their former selves. In 2009, the year before Walker was elected, the Wisconsin Education Association Council employed seventeen lobbyists. By 2019, they had just two. By most accounts, the reforms markedly improved Wisconsin’s government and its economy. The state realized savings of $5 to $7 billion per year, some of which went into support of small business and tax reductions. An estimated 42,000 jobs were created. Schools improved—particularly math scores in nonurban schools and overall quality in school districts that instituted merit pay. Union membership declined from 50 percent to 22 percent of public employees. It appears as if even Democrats are happy to get unions off their backs. Schools and agencies are manageable and work better, and the state is no longer saddled with a large operating deficit … Breaking union controls in Wisconsin required a kind of civil war, with four years of nonstop political and legal battles, and do not appear to be replicable in most states. Indeed, it appears that Walker was able to get elected initially only because, as the unions complained afterward, he disguised his intention to reform collective bargaining. Otherwise the unions would have gone to war earlier and made sure he wasn’t elected.

Many people don’t realize the extent to which public sector unions hurt the prospects for members of private sector unions. That happens because the vast costs public sector unions impose on the wider economy and society at large hurts the employment prospects of private sector workers. As Howard writes:

Every public dollar involves a moral choice. A dollar wasted is a dollar not available for some other worthy goal. Every neglected public need—whether to help the hungry, deal with climate change, fix the roads, or reduce tax burdens—has been compromised by the budgetary grip of public employee unions. Public unions’ indifference to wasteful inefficiency is matched by their rapacity in demanding benefits in the future that are not reasonably affordable … Public inefficiency dragged down the broader economy. “Unlike unions in the private sector,” Professor DiSalvo observes, “government unions have incentives to push for more public employment, which increases their ranks, fills their coffers with new dues, and makes them more powerful. Therefore, they consistently push for higher taxes and more government activity. Over the long term, this can stifle economic growth and pit public and private sector unions against each other.”

As Terry Moe describes the situation in his book Special Interest: Teachers Unions and America’s Public Schools:

[T]here is another difference [between private and public sector unions] that, if anything, is even more profound: the “employers” in the public sector are elected officials. To the extent that public sector unions can wield power in elections, therefore, they can literally select the “employers” they will be bargaining with, and who will make all the authoritative decisions about governmental funding, programs, and policy. Unlike in the private sector, then, the “employers” in the public sector are politicians who are not independent of the unions. Quite the contrary. In jurisdictions where unions have achieved a measure of political power, many public officials—especially Democrats, given their longtime political alliances with the unions—clearly have incentives to promote collective bargaining, give in to union wage and benefit demands, go along with restrictive work rules, add to the employment rolls, and protect existing jobs. That is so even if they know full well that the result will be higher costs and inefficiencies and that the larger population of citizens will not be well served.

Moe also points out that public sector unions hurt members of private sector unions because public sector unions can do damage to the larger economy, limiting the value of private sector retirement programs (which are linked to the performance of the economy generally), whereas all the while the pensions of public sector union members remain immune from the bad effects public sector union policies impose on the economy generally. As Moe writes:

[Teachers] have defined-benefit programs. With defined-benefit programs, the amount of the retirement annuity (usually with inflation safeguards) is “defined”: it is guaranteed. It does not fluctuate with the stock market or the economy and can be counted upon as future income.

As public sector unions have done increasing harm to the wider economy, private sector unions have shrunk. As Howard writes, “Today, only about 6 percent of the private workforce belongs to trade unions, down from a high of about 35 percent in the 1950s.” And as Zupan adds:

As of 2009, there were more members of public-sector unions (7.9 million) than private-sector unions (7.4 million) for the first time in US history … [T]he percentage of nonagricultural workers in the private sector who are union members has plummeted from 38 percent in the early 1950s to less than 7 percent today. By contrast, over the same period, public-sector membership has skyrocketed from 10 percent to 36 percent … An estimated 63 percent of federal workers are unionized … As federal employees have grown in number and acquired greater political influence, their compensation, relative to what is earned by comparable state and local government workers or private-sector employees, has increased.6 The premium was 20–40 percent over 1950–1990 and has grown since then. Based on US Bureau of Economic Analysis data, federal workers now earn an average of 78 percent more in total annual compensation than private-sector workers ($119,934 compared to $67,246) and 43 percent more, on average, than state and local government workers … DiSalvo provides further evidence that, after accounting for all forms of compensation, salary and fringe benefits, and the duration for which they hold office, state and local public employees are paid more than their private-sector counterparts. For example, as of 2015, most US public workers can expect a pension when they retire, whereas only 20 percent of private-sector workers receive such a fringe benefit. Private firms have stopped offering pensions, especially given today’s ever-more competitive and dynamic global marketplace … Now, private-sector pensions, even for unionized workers, are typically defined contributions for which employees pay the lion’s share while they are working. By contrast, public pensions largely are defined benefits where the government not only pays for most (if not all) of the benefit but also guarantees that the promised amount will be paid when the worker retires. Thus, while private-sector workers must worry about how financial market gyrations will affect the value of their retirement accounts, public employees have no similar concern.

In the next series of essays, we’ll examine the harm to public education caused by public sector unions.