Public Sector Unions – Part 1

How public sector unions lead to self-dealing, which results in unbalanced policies that help few at the expense of many.

What is a labor union? A labor union is a legal entity that is granted by law the exclusive right to bargain with the employer of the union’s members for worker compensation or other benefits. Because no one besides the “exclusive bargaining unit” of an existing union can legally negotiate with employers, union officials have a special legal duty to focus exclusively on benefits to their own members, to the exclusion of all the other concerns of everyone else in society. As I’ve written previously, in describing why teachers unions, for example, are legally prohibited from “putting children first”:

The Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act, for example, makes clear in section 501(a) that “The officers, agents, shop stewards, and other representatives of a labor organization occupy positions of trust in relation to such organization and its members as a group. It is, therefore, the duty of each such person, taking into account the special problems and functions of a labor organization, to hold its money and property solely for the benefit of the organization and its members …” Such union officials also have the duty “to refrain from dealing with such organization [the union] as an adverse party or in behalf of an adverse party in any matter connected with his duties.” Each of these obligations is considered a “fiduciary duty,” and if any senior union official violated them, they could be sued. What this means is that if a teachers union official ever actually did put the interests of children and children’s education before the union members’ interests in better wages and work benefits, that teachers union official could be sued, and be legally stripped of their position as a result.

So unions are required by law to focus solely on the best interests of their members, to the exclusion of the interests of all others. Indeed, in her biography of Frances Perkins, The Woman Behind the New Deal: The Life of Frances Perkins, FDR’s Secretary of Labor and His Moral Conscience, Kirstin Downey describes how the Secretary of Labor who presided over the creation of the first major federal labor union laws in the 1930’s came “to view unions as naturally self-protective and eager to preserve their own advantages” and “[i]n her opinion, labor leaders were seldom the selfless people that liberals imagined them to be.”

Union membership in the private sector is associated with inefficiencies, to the detriment of all workers at unionized factories. As researchers have found:

Using plant-level data from the Census Bureau, we show that in addition to paying higher wages and benefits, unionized plants have lower and less effective incentives. Unionized plants do not exhibit the same positive associations between incentives and investment and growth found in non-unionized plants. This effect holds among both non-managerial and managerial employees, although it has a more pronounced influence on the former group. Consequently, unionized plants experience higher rates of closure, reduced investment, and slower employment growth. We also find significant spillover effects within the firm: partially unionized firms not only offer higher wages but also maintain weaker incentives in their non-unionized plants compared to their industry peers. These effects are economically significant and are half of our estimated reduction in incentives in unionized plants. This pattern aligns with the hypothesis that incentives in non-unionized plants create disutility for the median worker. Spillovers reduce employment and efficiency and make firms less attractive as potential targets, thus reducing the market’s effectiveness in allocating corporate assets. By leveraging recent changes in state-level right-to-work laws, we provide causal evidence that states that adopt such laws experience a boost in employment and investment.

But an additional problem arises with public sector unions — that is, unions that represent workers that work for local, state, or federal governments. That’s because public sector unions -- unlike private sector unions that represent people who work for private businesses -- “preserve their own advantages” with taxpayer money, which is handed out by the politicians the union is “negotiating” with.

As Philip Howard writes in his book Not Accountable: Rethinking the Constitutionality of Public Employee Unions:

The two teachers unions (the National Education Association and the American Federation of Teachers) have about 4.6 million members, including retirees. Other public unions include the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) with roughly 1.3 million members; the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), which represents roughly one million public employees; the Fraternal Order of Police, with 357,000 members; the American Federation of Government Employees (AFGE), with 300,000 members; and the National Treasury Employees Union (NTEU), with 80,000 members. Overall, 35 percent of public employees in America belong to unions: 25 percent in federal government, 30 percent in state government, and 40 percent in local government. In states that mandate collective bargaining, the concentration is much higher: half to two-thirds of all public employees in California, Connecticut, Illinois, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island belong to unions.

And in his book Inside Job: How Government Insiders Subvert the Public Interest, Mark Zupan wrote in 2017:

The numbers and influence of public employees have grown at levels beyond the federal level. The monopoly power of state and local government employees, with its attendant fiscal impact, also has increased in recent decades. Between 1958 and 1984, a majority of states enacted legislation promoting collective bargaining rights for public employees. Whereas only three states permitted collective bargaining by state and local employees in 1959, thirty-three states did as of 1980. Today, only three states entirely proscribe collective bargaining by public employees (North and South Carolina and Virginia).

Since then, however, Virginia has also come to allow collective bargaining by public employees under a 2020 state law granting local governments and school boards authority to allow collective bargaining. The city of Alexandria, where I live, passed an ordinance allowing public sector collective bargaining that took effect in May 2021, and Interim Alexandria Public Schools Superintendent Melanie Kay-Wyatt told the mayor she will work closely with City Manager Jim Parajon’s office in creating a collective bargaining structure.

My kids will have left the public school system here by the time the negative effects of unions manifest themselves in spades, but still we should all be concerned with the next generation. And even where I live, where collective bargaining by public employees was until recently prohibited, people are keenly aware of the role teachers unions played in the prolonged closure of public schools during the COVID pandemic. As reported in the New York Times:

[Unlike teachers unions nationwide] [m]any other education leaders took a different approach in 2020 and came to favor a faster reopening of schools. In Europe, many were open by the middle of the year. In the U.S., private schools, including Catholic schools, which often have modest resources, reopened. In conservative parts of the U.S., public schools also reopened, at times in consultation with local teachers’ unions. Some people did contract Covid at these schools, but the overall effect on the virus’s spread was close to zero. U.S. communities with closed schools had similar levels of Covid as communities with open schools, be they in the U.S. or Europe. How could that be? By the middle of 2020, there were many other ways for Covid to spread — in supermarkets, bars, restaurants and workplaces, as well as homes where out-of-school children gathered with friends. Despite the emerging data that schools were not superspreaders, many U.S. districts remained closed well into 2021, even after vaccines were available. About half of American children lost at least a year of full-time school, according to Michael Hartney of Boston College. And children suffered as a result. They lost ground in reading, math and other subjects. The effects were worst on low-income, Black and Latino children. Depression increased, and the American Academy of Pediatrics declared a national emergency in children’s mental health. Shamik Dasgupta, a philosopher at the University of California, Berkeley, who became an advocate for reopening schools, called the closures “a moral catastrophe.” … Dasgupta, the Berkeley philosopher, has a thoughtful way of framing this failure. As he wrote to me in an email: “It is clear that extended school closures were a mistake — they harmed children while having no measurable effect on the pandemic. It is also clear that teachers’ unions were a major factor behind the closures. But remember that the unions were just doing their job. Their remit is to advocate for their members and that is exactly what they did.” Seen like this, the problem was not the teachers’ union per se — I am personally in favor of public sector unions — but the absence of a comparable organization at the bargaining table to represent the interests of students and their caregivers. It was a failure of democratic decision-making.

That “failure of democratic decision-making” caused by collective bargaining by public sector employees extends far beyond COVID policies into nearly every aspect of American life today. That topic will be the subject of this series of essays.

As Howard writes, public sector unions are unique in that:

public sector unions soon set out to do what is impossible in the private sector—to “capture” the officials on the other side of the table … [U]nions in the public sector can get what they want by helping friendly politicians get elected. As labor leader Victor Gotbaum put it, “We have the ability, in a sense, to elect our own boss.” Public sector “bargaining” is a misnomer; the process is more like a transaction: benefits at the bargaining table in exchange for campaign support.

That’s not an issue with private sector unions. As Howard explains:

Trade union negotiations basically divide the pie of profit between capital and labor. Bargaining is constrained by the distinct economic risks on each side. Demanding too much may cause the business to close or move to other states or overseas. Demands that reduce profit—for example, with inefficient work rules—may also be counterproductive, because they leave less profit to divvy up. Trade unions learned this the hard way by overbearing demands on car makers and other industrial companies in the 1960s and 1970s, which had the effect of driving jobs elsewhere.

But public sector unions are much, much different. As Howard writes:

The differences between public and private bargaining are differences in kind, not degree. Government bargaining has few market constraints. Government can’t go out of business, so unions can demand ever more—a kind of one-way ratchet that never stops raising public costs. Where industry sees inefficiencies as a deal killer, many politicians readily accede to inefficiencies as a way to benefit public employees. The more jobs, the better … Because government isn’t run for profit and has nothing like quarterly earnings reports, it’s hard for the public to see profligate spending and inefficiencies … Public unions have made rigid management controls into a kind of entitlement—strict seniority and supervisory restrictions are union “accomplishments.” Most unionized businesses, by contrast, would never accept deliberate inefficiencies and rigidities. They could not long stay in business by delivering mediocre products and services at a high price … The most important distinction between public and private bargaining, as noted, is that public management is responsive to political inducements, not the marketplace. Instead of bargaining over the split of economic gain, the parties are seeking different benefits altogether—public officials want political support, and unions want employee entitlements. Instead of dividing the pie, they offer each other inducements. What makes this negotiation collusive is that they’re negotiating with the public’s money for their parochial benefits. Labor lawyer Theodore Clark early on diagnosed the conceptual flaw: “Collective bargaining is premised on … two parties which are essentially in adversarial roles” where “neither party should be able to interfere with the other party’s bargaining representatives.” “The political aspects of public sector collective bargaining,” Clark concluded, “jeopardize the very premise on which collective bargaining exists.” Payoffs that would be unlawful in business bargaining have become a common feature of public bargaining—unions are making massive campaign donations to the politicians with whom they will then be negotiating … Elected officials are supposed to govern for the common good, not cede control to unaccountable public employees.

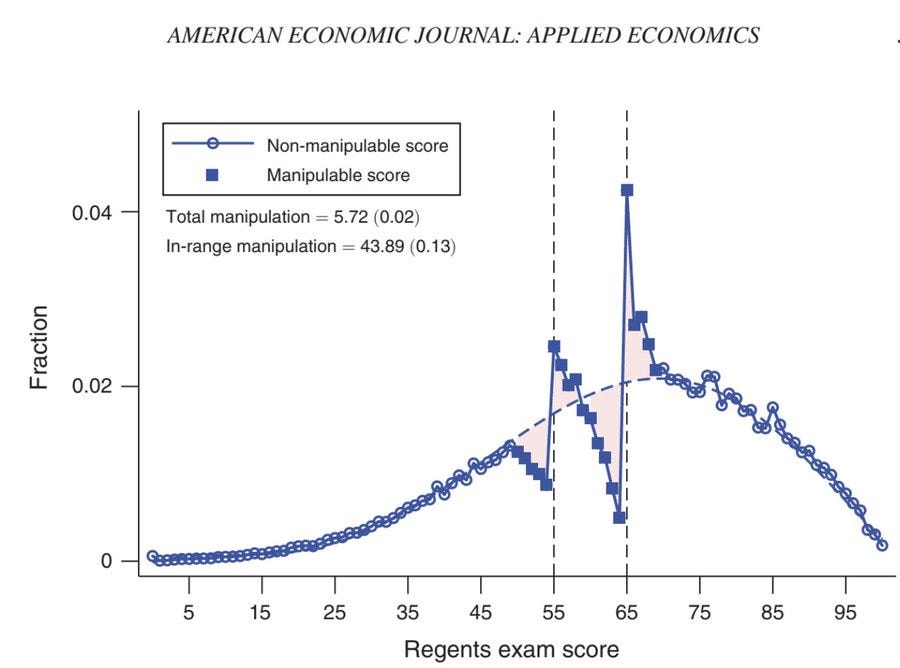

When public sector unions are instrumental in electing those with whom they are supposed to be “negotiating,” they run afoul of the basic rule of due process: namely (as was explored in a previous series of essays) that people should not be judges in their own cases. Indeed, in New York City, teachers unions recently succeeded in allowing teachers at a student’s own school to grade their standardized exams designed to evaluate school performance, a practice previously found to have been manipulated to push certain students over the “pass” line. According to a January, 2023, article in Chalkbeat New York:

New York City schools will once again grade their own students’ Regents exams, a policy that officials scrapped a decade ago amid concerns that educators were systematically nudging scores over the passing cutoff. The city’s education department informed schools last month that starting this school year, “most Regents exams” that students take will be scored by teachers in their own schools, according to a memo obtained by Chalkbeat. Schools have already begun grading their own Regents exams that were administered last week. Generally, students must pass four or five Regents exams to graduate from high school. The move represents a significant shift, and comes as state officials are reconsidering the role of Regents exams. For more than 10 years, New York City schools have largely sent their Regents exams to centralized sites where educators from other campuses graded the exams. Some school leaders praised the change, along with the city’s teachers union, which pressured the city to abandon centralized grading. But some experts worry that teachers will once again unfairly bump up familiar students’ scores … City officials began centrally grading Regents exams in the wake of a 2011 Wall Street Journal investigation that found students were much more likely to earn the exact number of points needed to pass the exam than earn a score just below the cutoff — evidence that teachers gave students a boost to help them pass. On the state level, officials banned teachers from grading their own students’ exams and ended a policy that required re-scoring exams that were just below the passing threshold. After those policy changes, evidence that educators were manipulating scores vanished, researchers found … “What we observed back when teachers graded their own students’ Regents exams is very clear evidence that they use their discretion to manipulate the Regents scores of students who were close to the threshold for passing the exam,” said Thomas Dee, a professor at Stanford University who co-authored a [2019] study about the grading irregularities … Between 2004 and 2010, when schools were allowed to score their own students’ exams, researchers estimated that 6% of all New York City Regents exams were manipulated upward. (There were similar signs of manipulation across the state.)

In the next essay in this series, we’ll examine the source of the power of public sector unions.