Primal World Beliefs

How people's views of the nature of the world in general impact their own well-being in life.

This series will explore the ramifications of our perceptions regarding whether or not the world, in general, is a dangerous place. It will focus on a fascinating and relatively new area of research into what have come to be called “primal world beliefs.”

In an earlier essay series, we explored the effects on well-being of one’s sense as to whether one has more control over what happens in our lives (“internal locus of control”) or less control over what happens in our lives (“external locus of control”). Those feeling generally influence people’s success in life, with those feeling they are more subject to external forces generally having less happy lives. The study of primal world beliefs also aims at finding associations between attitudes and well-being, but it comes at the issue from a different perspective. That is, rather than focusing on the influence of our internal sense of control over our lives, the study of primal world beliefs focuses on the influence of our perceptions of the state of the external world and how that relates to our well-being.

As the authors of the first major study of primal world beliefs write:

We introduce a set of environment beliefs—primal world beliefs or primals—that concern the world’s overall character (e.g., the world is interesting, the world is dangerous) … These beliefs [are] strongly correlated with many personality and wellbeing variables (e.g., Safe and optimism, r .61; Enticing and depression, r .52; Alive and meaning, r .54); and explained more variance in life satisfaction, transcendent experience, trust, and gratitude than the BIG 5 [Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism] (3%, 3%, 6%, and 12% more variance, respectively). In sum … primals plausibly shape many personality and wellbeing variables, and a broad research effort examining these relationships is warranted … This article introduces a class of environment beliefs that may influence wellbeing and personality.

The authors continue:

[P]rimals usually take the form “the world is X” where X is one or two basic words concerning a single-faceted concept like beautiful or dangerous … Primals concern the world as a whole, and thus what is typical of most things and situations … [P]rimals concern an individual’s broadest psychologically meaningful habitat … Like other beliefs, primals are expected to dynamically direct attention; organize, simplify, filter, and fill in information; and guide action. In sum, primals are one’s implicit answers to the question “what sort of world is this?” … In our tentative model, primals operate like other beliefs. For example, some may see the world as a negative place. This view would inform a base-rate of negativity that might alter ambiguity interpretation toward seeing situations as miserable, meaningless, and getting worse. In worlds where fortunate events are considered exceptions, pessimism appears prudent and optimism naïve. Conversely, some may see the world positively: most situations are enjoyable, safe, and naturally tend to work out—the unknown hides further wonders. When misfortune is rare, pessimism appears profitless or paranoid, and optimism sensible. In sum, both pessimists and optimists might theoretically be realists who happen to disagree about what is real … [T]he belief that a situation is dangerous should increase neurotic behaviors. If so, a belief that the world as a whole is dangerous should increase neuroticism scores. Likewise, curiosity, which makes little sense in contexts offering low return on attentional investment, may be part of a reaction to a belief that the world is actually full of fascinating things.

This is important area of study because:

Individuals may not realize others hold different primals … [For example] the relationship between beliefs about the ubiquity of germs and one’s personal susceptibility to infection suggests individuals think their own primals describe everyone’s reality … [and] many personality variables and wellbeing outcomes are driven in part by the (perceived) external situation rather than internal disposition.

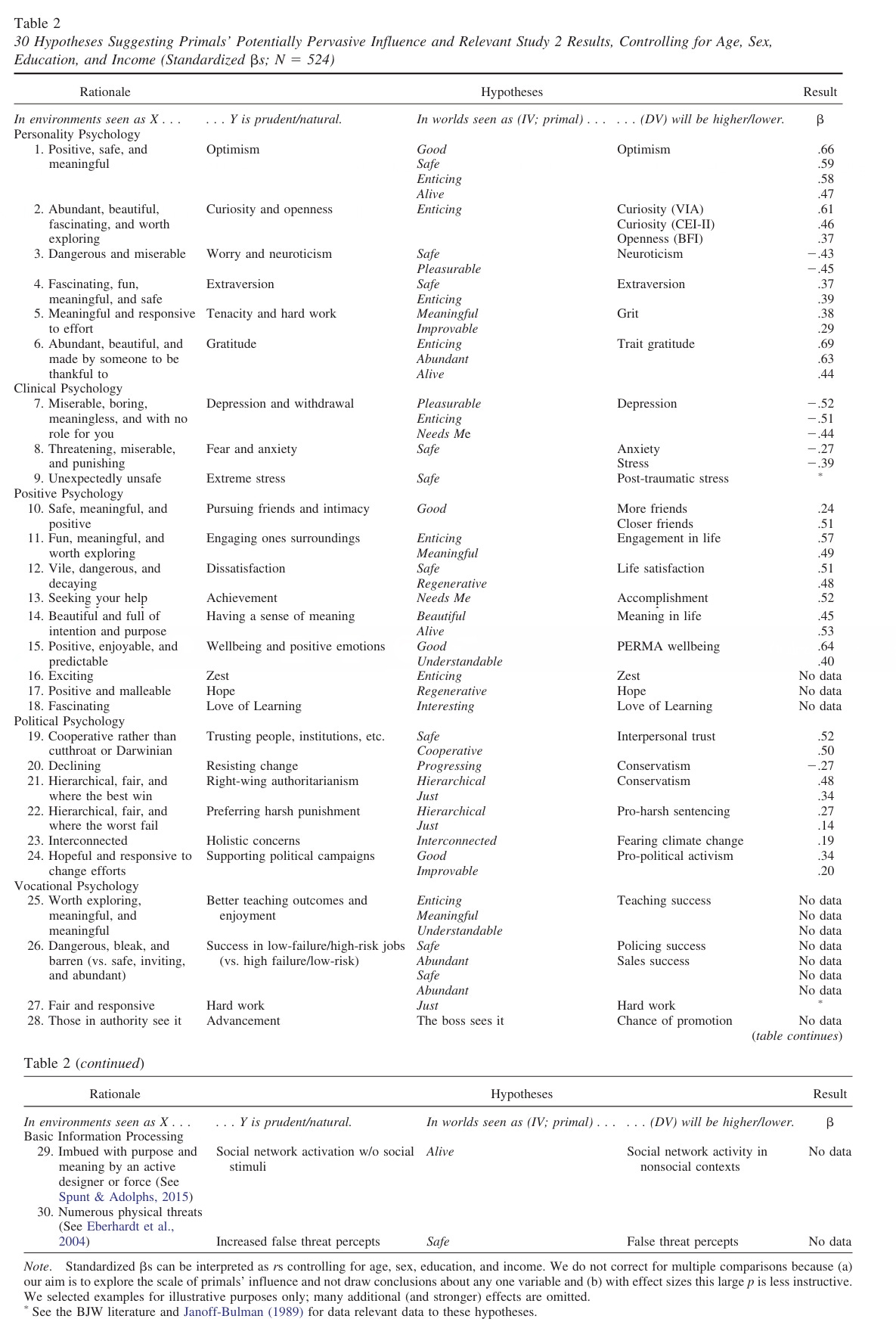

The following table lists many examples of the sorts of effects on personality that might follow from any given sense of the general nature of the world at large:

The authors also point to a related line of study:

Belief in a just world (BJW) holds that the world is a place where one gets what one deserves and deserves what one gets. Over 30 studies using several validated scales suggest significant relationships between BJW and many salient variables. These studies show that, causal or not, individuals act in ways that appear optimal, given their primals. In general, those high in BJW are more hardworking (since the world rewards effort), more prosocial (since the world rewards kindness), more successful (since they work harder and are nicer) …

As a result of their initial study, the authors found the following:

This article has introduced a category of beliefs, identified 26 of them, and found that, in the samples we gathered, these beliefs met three critical correlational benchmarks. (a) Primals were stable; people appear to spend years—perhaps decades—holding the same primals. (b) Primals vary considerably from person to person; PI scores vary on 26 fairly normal, unimodal distributions, suggesting individuals often profoundly disagree, perhaps without realizing the extent of disagreement. (c) Primals are highly predictive, often above and beyond BIG 5 traits; we found expected patterns of relationships, many large, between primals and over 100 personality, clinical, wellbeing, political, religious, and demographic variables.

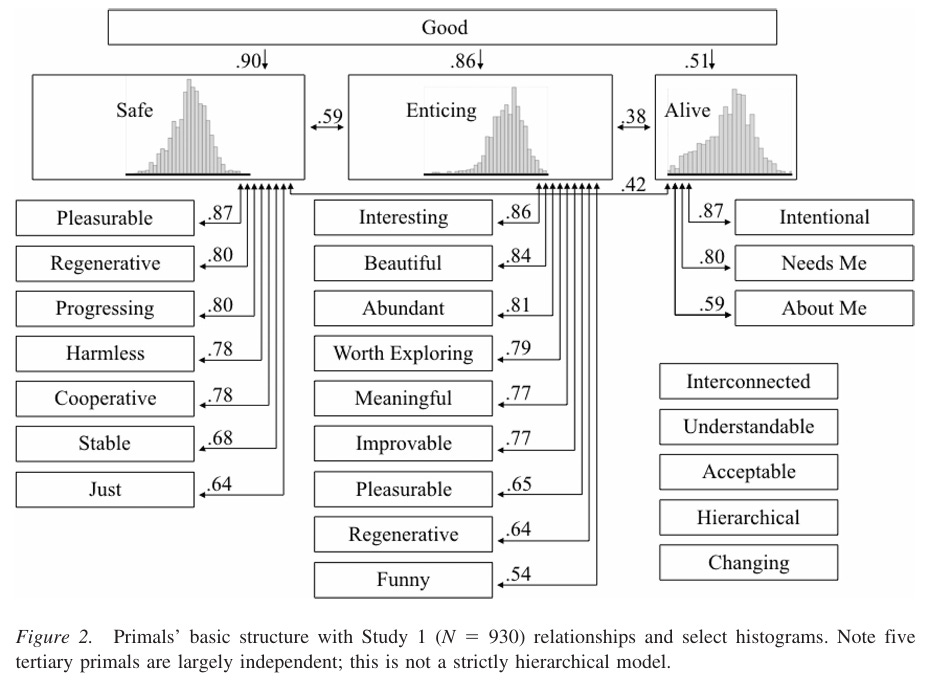

They also describe how the world may seem to those scoring low and high on the three key primals, namely Safe, Enticing, and Alive:

Those low on Safe see a Hobbesian world defined by misery, decay, scarcity, brutality and dangers of all sorts. Base rates for hazards—from germs to terrorism to getting stabbed in the back— are generally higher. In response to chronic external threats, they remain on high alert, often viewing the nonvigilant as irresponsible. Those high on Safe see a world of cooperation, comfort, stability, and few threats. To them, things are safe until proven otherwise, vigilance appears neurotic, risk is not that risky, and, in general, people should calm down. Those low on Enticing inhabit dull and ugly worlds where exploration offers low return on investment. They know real treasure—truly beautiful and fascinating things—is rare and treasure-hunting appropriate only when it’s a sure bet. Those high on Enticing inhabit an irresistibly fascinating reality. They know treasure is around every corner, in every person, under every rock, and beauty permeates all. Thus, life is a gift, boredom a misinformed lifestyle choice, and exploration and appreciation is the only rational way to live … Likewise, we expect other primals and combinations of primals suggest particular life approaches. For convenience, Figure 2 lists all primals the [studied] measures, presents the structure we found across studies, shows where Safe, Enticing, and Alive fit, and displays their histograms.

The authors conclude:

[H]uman action may not express who we are so much as where we think we are and much of what we become in life —much joy and suffering —may depend on the sort of world we think this is.

In another paper the author discusses the possible links between various attitudes and their effects on life experience, drawing on other research:

Gratitude

Lomas et al. (2014) theorize that state gratitude requires the perception that a given situation involves (a) good things to be grateful for and (b) someone to be grateful to. Likewise, persistent patterns of gratitude (i.e. dispositional gratitude) may never develop without the perception that this world is (a) overflowing with wonderful things to be grateful for (Enticing, r = .71, page 312) and (b) animated by someone to be grateful to (Alive, r = .45, page 312). If so, strengthening these primals will increase gratitude.

Curiosity

People rarely search for what they do not expect to find. Likewise, persistent patterns of curiosity may largely develop in reaction to the perception that this world is full of Interesting phenomena (r = .59, page 318) and Worth Exploring (r = .42, page 318). If so, strengthening these primals will increase curiosity.

Hope (optimism)

People are naturally optimistic in situations believed to be inherently positive and with a natural tendency to heal, flourish, and otherwise improve. Likewise, patterns of optimism may develop largely in reaction to the perception that this world is fundamentally Good (r = .67, page 312) and Regenerative (r = .55, page 319). If so, strengthening these primals will increase optimism.

Interpersonal trust

People are less trusting in contexts perceived as dangerous. Likewise, persistent patterns of interpersonal trust may develop partly in reaction to the view that the world is generally Safe (r = .55, page 312). If so, strengthening this primal will increase trust.

Self-efficacy

People believe they can change a situation when they see themselves as competent enough, but also when they see the situation as plastic enough. Likewise, a persistent pattern of self-efficacy may develop partially in response to the underlying belief that the world is Improvable (r (122) = .59, page 503). If so, strengthening this primal will increase self-efficacy.

Wellbeing outcomes

Positive emotions

Joy, contentment, and other positive emotions are difficult to experience in situations seen as awful. Likewise, positive emotions may more often elude those who see this world as awful (low Good, r = .63, page 312). If so, changing the belief will increase positive emotions.

Engagement

It is difficult to engage in places seen as boring. Likewise, a pattern of decreased engagement may result from seeing the world as dull and not worth exploring (low Enticing; r = .58, page 312). If so, changing that perception will increase engagement.

Meaning

It is difficult to achieve a sense of meaning in situations involving trivial matters, important matters impervious to change, or important matters that will change but without needing one's help. Likewise, a persistent sense of meaninglessness may develop in response to the belief that the world is a place where few things matter (low Meaningful; r = .60, page 319), little can be changed (low Improvable; r = .40, page 319), and one's efforts are not needed (low Needs Me; r = .63, page 319). If so, changing these beliefs will increase meaning.

Life satisfaction

It is difficult to find satisfaction in miserable, barren places. Likewise, life satisfaction may be partly a reaction to the believe that the world is generally Pleasurable (r = .53, page 320) and Abundant (r = .47, page 313). If so, strengthening these beliefs will increase life satisfaction. Overall wellbeing Finding happiness is difficult when residing in places one abhors. Likewise … achieving happiness in a world perceived as a s**thole is highly unlikely (i.e. low Good; r = .66, page 313). If so, changing that perception will increase overall wellbeing.

One practical implication of the study of primal world beliefs is discovering the extent to which people with attitudes toward the world that are associated with bad outcomes in life can alter their own primal perceptions in ways that improve their life chances. As the author writes:

Of relevance to understanding the current state of primals research may be [Aaron T.] Beck’s (e.g. Beck, 1963; Beck et al., 1979) experience convincing reluctant clinical researchers operating under a behaviorist paradigm that beliefs similar to primals shape depression. At first, despite similarly promising theory and correlational relationships, Beck’s suggestion about beliefs was dismissed or ignored. This changed only after he designed an intervention – Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) – on the premise that these beliefs shaped depression and demonstrated CBT’s effectiveness. Half a century later, CBT is the most widespread form of therapy and the role of beliefs in depression is broadly acknowledged … [I]n addition to CBT, a variety of interventions are already known to alter similar beliefs and many anecdotal accounts describe how primals change after, say, a semester abroad, a spiritual experience, a transformative friendship, and so forth [M]any individuals may come to hold their primals without deliberation or debate, and may be thus open to alternatives if they knew of them. Unlike undeniable beliefs dictated by sensory experience such as the sky is blue, the vast and heterogenous dataset that is the world could be used to sustain various contradictory perspectives. It matters where one directs attention and attention is often controllable.

The author then writes that some useful primal interventions might include the following areas:

Educational

Some interventions may educate subjects on key issues. For example, initial research suggests negative primals are often perpetuated by demonstrably false beliefs about primals (i.e. meta-beliefs), including the assumption that most people see the world as we do (i.e. false consensus bias); one’s negative experiences leaves no choice (e.g. I have to see the world as barren because I grew up poor); or utility demands it (e.g. seeing the world as dangerous keeps me safe) …

Attentional

Several biases – especially confirmation bias – focus attention on information consistent with pre-existing views, thereby perpetuating primals. Thus, like other PPIs, successful primals interventions may involve deliberate appreciation of disconfirming evidence and altering attentional habits.

In another paper, the authors examine why “Parents think – incorrectly – that teaching their children that the world is a bad place is likely best for them.” In that paper, the authors write:

Primal world beliefs (‘primals’) are beliefs about the world’s basic character, such as the world is dangerous. This article investigates probabilistic assumptions about the value of negative primals (e.g., seeing the world as dangerous keeps me safe). We first show such assumptions are common. For example, among 185 parents, 53% preferred dangerous world beliefs for their children … As predicted, regardless of occupation, more negative primals were almost never associated with better outcomes. Instead, they predicted less success, less job and life satisfaction, worse health, dramatically less flourishing, more negative emotion, more depression, and increased suicide attempts.

As they elaborate:

92% of parents thought that seeing the world as safe to very safe (i.e., scores of 4–5 on a 0–5 scale) is not best for their children … Across six samples – 4,535 subjects involving 48 occupation groups – negative primals were almost never associated with positive outcomes … In the [majority] 1,854 relationships (99.7%), more negative primals correlated with worse outcomes, often dramatically worse. For example, Safe world belief was strongly correlated with increased life satisfaction across all six samples and in the vast majority of occupations, including among jobs where the ability to spot threats are useful, such as law enforcement. Effect sizes indicated that, generally speaking, negative primals correlated with slightly less job success, moderately less job satisfaction, moderately worse health, substantially increased negative emotion, substantially increased depression symptoms, slightly increased lifetime suicide attempts, substantially decreased life satisfaction, and dramatically decreased overall psychological flourishing … [S]eeing the world as very positive was associated with more positive outcomes than seeing the world as moderately positive … [F]or most primals, a sizeable minority of parents – in one case a majority – reported that the best way to prepare their children to navigate life was to teach them the world is in various ways a bad place, specifically that it is dangerous, unfair, rarely funny, unstable, cut-throat, and getting worse … In sum, a robust correlational relationship exists between more negative primals and more negative outcomes, even when comparing positive beliefs to positive beliefs, even when comparing within occupation … [These studies] show that many parents seek to teach negative primals to their kids, associating negative primals with better life outcomes, but these associations do not hold. Across samples, work professions, and out comes, negative primals were nearly always correlated with net negative outcomes, often strongly.

Researchers in this field have also examined the following question: to what extent might a general view that the world is good be associated with higher income, or other indicators of “privilege”? In an article titled “Despite popular intuition, positive world beliefs poorly reflect several objective indicators of privilege, including wealth, health, sex, and neighborhood safety,” the authors write:

We tested whether generalized beliefs that the world is safe, abundant, pleasurable, and progressing (termed “primal world beliefs”) are associated with several objective measures of privilege … Three studies (N = 16,547) tested multiple relationships between indicators of privilege— including socioeconomic status, health, sex, and neighbor hood safety— and relevant world beliefs, as well as researchers and laypeople's expectations of these relationships … Studies 1– 2 found mostly negligible relationships between world beliefs and indicators of privilege, which were invariably lower than researcher predictions … [The results imply] that knowing a person's demographic background may tell us relatively little about their beliefs (and vice versa).

As the authors elaborate:

Despite occupying the same planet, people vary greatly in whether they see the world as good or bad, safe or dangerous, just or unfair … One possibility is that primal world beliefs (e.g., concerning how dangerous the world is) are updated— like Bayesian priors— after experiencing that quality (e.g., by living in a dangerous neighborhood). If so, the quality being ascribed to the world (e.g., “danger”) reflects whether the person has extensively experienced that same quality in their own life. This is termed a “retrospective” account of primal world beliefs. If retrospective accounts are generally accurate, knowing some body's experiences of privilege would reveal much about the way they likely see the world, and vice versa. A wealthy person, for example, might live in a safer environment with more pleasurable experiences, and more opportunities, thus viewing the world more positively than those in more difficult circumstances. Importantly, we use the term “privilege” narrowly here as shorthand for people's health, wealth, demographics, and local surroundings … If this simple retrospective account is true, and primal world beliefs are largely just a reflection of a person's objective experiences, this would be unfortunate for clinicians and others exploring how these beliefs might be altered to increase well-being. The correlation between Good world belief and well-being is large … If Good world belief is strongly tied to simply enjoying a privileged life, then, for many, positive primals might remain forever out of reach. If, however, positive primals are within reach but merely believed to be out of reach (see opening quote), this too may be detrimental to increasing well-being because people may be less likely to attempt change.

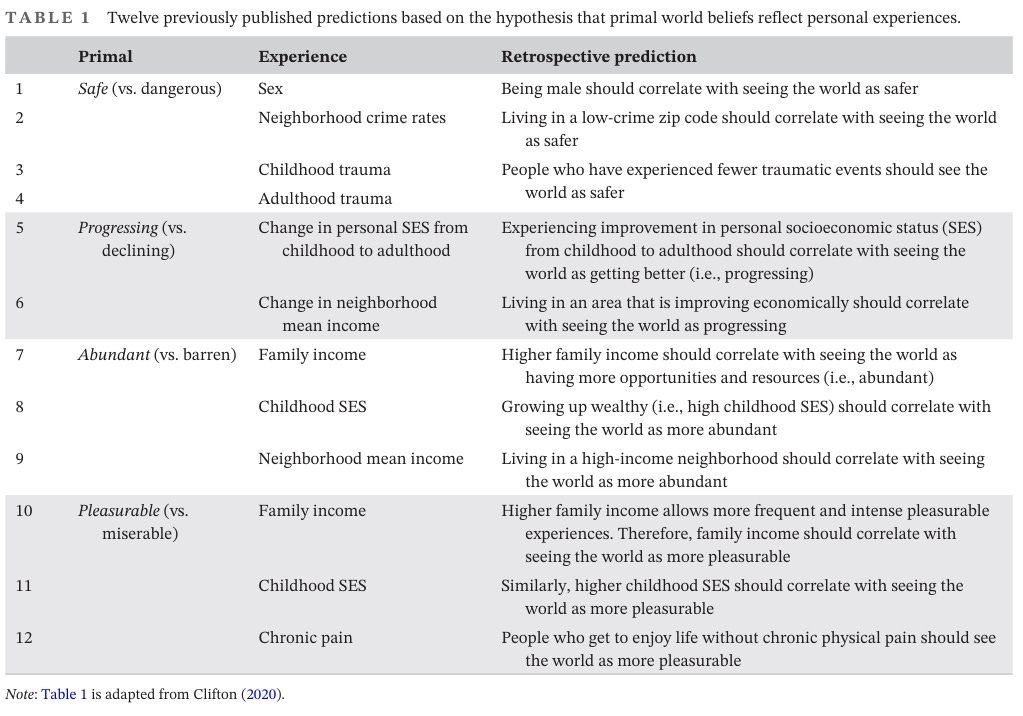

The researchers lay out a table listing various predictions regarding what they might find as to how primal world beliefs reflect personal experiences.

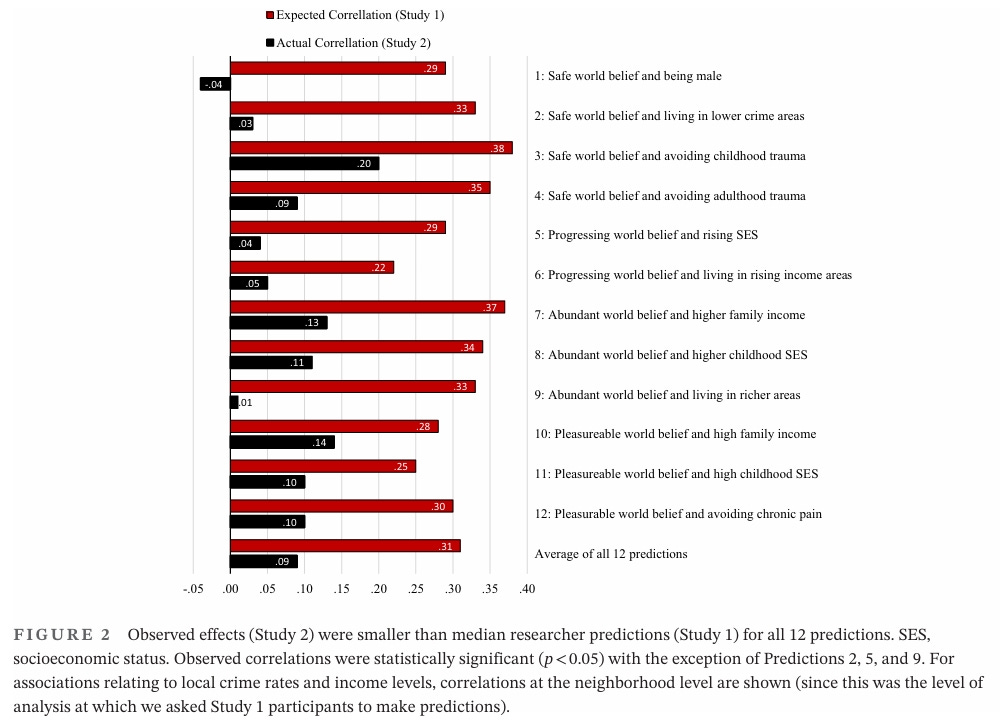

The researchers found the following results:

For all 12 predictions, laypeople and researchers expected substantial associations in the hypothesized direction. For example, the majority of laypeople (84.4%) expected that those with higher family incomes would see the world as “substantially more” or “much more” abundant.

One of the studies reported on asked “Do positive primal world beliefs actually reflect privilege in these 12 ways?” They found the following:

Across all samples and the 12 predictions, positive primal world beliefs were poor reflections of privilege (Figure 2). Average correlation across the 12 predictions was |r| = 0.09 (1.0% shared variance— see Figure S1 for correlations shown as r2), rather than the researcher prediction of |r| = 0.34 (9.9% variance shared). Thus, researcher- predicted effects were on average 3.8 times higher than observed effects (based on r) or 9.7 times higher (based on % shared variance, arguably a more appropriate way to compare the relative size of covarying relationships) … There was no evidence that women see the world as less safe than men, with a small relationship emerging in the opposite direction, r(14, 479) = 0.04, 95% CI [0.02, 0.06], p < 0.001 … People living in neighborhoods (i.e., five-digit zip code) with more violent crime did not score lower on Safe world beliefs, r(2, 933) = −0.03, 95% CI[−0.01, 0.07], p = 0.104 (r2 = 0.001) … There was a modest negative relationship between self- reported Safe world beliefs and childhood trauma rs (1042) = −0.20, 95% CI [−0.26, −0.14], p < 0.001 (r2 = 0.040) and a smaller negative relationship between Safe and trauma in adulthood, rs (1042) = −0.09, 95% CI [−0.15, −0.03], p < 0.001 (r2 = 0.008) … Change in self- reported social class across one's lifetime was not associated with seeing the world as getting better, (i.e., Progressing world belief, r(1, 929) = 0.04, 95% CI[−0.01, 0.08], p = 0.093 (r2 = 0.002)) … People in neighborhoods that were getting wealthier saw the world as getting better to a very small degree (i.e., Progressing, r(2, 789) = 0.05, 95% CI[0.01, 0.09], p = 0.008 (r2 = 0.003)) … People who described their parents were from a higher socioeconomic group saw the world as slightly more Abundant than average, r(3, 400) = 0.11, 95% CI[0.08, 0.14], p < 0.001 (r2 = 0.012) … People with higher family incomes saw the world as slightly more Abundant r(3, 450) = 0.13, 95% CI[0.10, 0.16], p < 0.001 (r2 = 0.017) … People currently living in wealthier neighborhoods did not score significantly higher on Abundant world belief r(2, 781) = 0.01, 95% CI[−0.10, 0.11], p = 0.904 (r2 < 0.0001) … We found similar results at county- and state-level: there was no correlation between people living in wealthier counties and seeing the world as abundant, r(8, 650) = −0.02, 95% CI[−0.07, 0.04], p = 0.510 (r2 = 0.0004) … People with higher family incomes saw the world as slightly more Pleasurable than those with lower incomes, r(2, 926) = 0.14, 95% CI[0.10, 0.18], p < 0.001 (r2 = 0.02) … Parents' socioeconomic class was associated with seeing the world as slightly more Pleasurable based on both the single-item measure, r(2, 894) = 0.11, 95% CI [0.07, 0.14], p < 0.001 (r2 = 0.01) … People who reported experiencing chronic pain saw the world as slightly less Pleasurable than those who did not, r(1, 042) = −0.10, 95% CI[−0.16, −0.04], p = 0.001 (r2 = 0.01) … Study 2 found these 12 indicators of privilege were weakly related to positive primals, with the nearest exception regarding extremely negative personal life experiences.

The authors make the following remarks regarding these findings:

Contrary to popular intuition, positive primal world beliefs were poor indicators of a privileged background … the popular expectation that there should be substantial correlations between these experiences and seeing the world as Safe, Abundant, Pleasurable, and Progressing. But researcher expectations of the strength of 12 predictions linking privilege and world belief (mean 9.9% variance shared) were on average almost 10 times greater than observed associations (mean 1.0% variance shared in Study 2; N = 14,481). For example, researchers thought Abundant world belief would correlate with living in wealthy neighborhoods at r = 0.33 when it actually correlated at r = .01 … The strongest relationship found in Study 2 was between childhood trauma and the belief that the world is a dangerous place (Predictions 3 and 4) … The fact that most relationships tested here showed either no correlation or negligibly small correlations suggests that personal life events either exert less influence on people's beliefs about the world than is widely thought or do so less systematically.

Query then whether people’s primal beliefs may come instead from what they see and read in the media, or from what they are taught.

The authors continue:

If personal experiences play only a minor role in shaping world beliefs, a key goal for future research is to identify which factors do lead to the substantial variation in how people see the world. One possibility is that hereditary factors play an important role in world beliefs, as they do with many other individual differences … Similarly, of course, nonbiological transmission from parents could also be influential, as could social transmission from peers or celebrities. Future research on world beliefs would do well to examine the relative influence of all these factors as well as interactions between them … [S]ome individuals believe themselves “locked in” to certain beliefs about the world based on their sex, where they grew up, negative life experiences, and so forth. Learning that the way most individuals see the world is not an inevitable product of these backgrounds might increase hope in the efficacy of therapy aimed at changing perspectives on the world.

The authors then conclude as follows:

This article has explored whether primal world beliefs closely reflect personal experiences. We found that knowing that a person holds positive (or negative) primal world beliefs revealed little about how privileged (or underprivileged) their lives had been, at least relating to the 12 indicators we examined. This contradicted the intuitions of many researchers and laypersons, including Study 1 participants and the participant quoted at the start of this paper, who was convinced that the reason they personally see the world as a barren place is because they are poor. If intuitions on how primal world beliefs arise are reliably inaccurate in this way, the pathway to a more positive worldview is perhaps not as simple as having a better life or even making the world better. Independent efforts may be required to improve both the world we live in and our attitudes towards it.

All educators should consider whether or not their methods of teaching are tending to encourage people to view the world as a place of injustice and danger or a place of opportunity and wonder, because those worldviews have serious life consequences.

As Robert Pondiscio writes:

Maya is 13 years old and in eighth grade. First period is English, where her class is reading a young adult novel about a teenage girl who self-harms, spirals into depression, and eventually attempts suicide. Her teacher praises the book for its honesty and “unflinching emotional truth.” After a brief discussion, the class writes about how trauma shapes identity. Second period is social studies. Today’s reading assignment comes from the 1619 Project, followed by a worksheet asking students to reflect on how racism is “baked into the structure of American life.” Last week, students read a chapter from A People’s History of the United States, by Howard Zinn, and discussed whether the U.S. was founded to protect the wealthy at the expense of everyone else. Maya takes notes quietly, worried she might say the wrong thing. In science, the class is studying climate change. The teacher plays a documentary that includes images of wildfires, melting glaciers, and disappearing coastal towns. Maya learns that humanity will face catastrophic collapse if global carbon emissions do not reach “net zero” by the time she’s in her thirties. During lunch, she tells a friend she’s not sure she wants to have kids someday. In the afternoon, Maya joins her “action civics” project group. Their capstone project is about gun violence. They’re creating a slide deck and organizing a letter-writing campaign. The project guidelines encourage students to “identify a systemic injustice” and “propose a structural solution.” Her group adviser urges them to “center” their personal stories. Tomorrow is a half day. Teachers will spend the afternoon in professional-development workshops on “trauma-informed pedagogy,” where they’ll learn to spot signs of anxiety, disengagement, and despair in students — and to treat these as evidence of trauma. Almost no one will consider the possibility that we are the ones traumatizing students. If you spend time in American classrooms today, especially in schools shaped by the dominant ideas of social and emotional learning (SEL) and trauma-informed pedagogy (TIP), you might get the impression that the world is a broken and dangerous place — and that wise and loving adults equip children to navigate it successfully by making them aware of just how bad things are. We think we’re helping them. But what if we’re not? That question lies at the heart of a compelling and underappreciated body of research led by Jeremy Clifton, a psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania … Clifton’s research has not made its way into teacher-training programs, education-policy debates, or district SEL initiatives. The only mention I’ve found of it in a publication aimed at teachers is a 2022 Education Week interview in which Clifton offered a quiet warning: “Don’t assume teaching young people that the world is bad will help them. Do know that how you see the world matters.” This quiet warning, if heeded, could spark a revolutionary change in American education. It could also guide those seeking to respond more productively to the mental health crisis afflicting America’s children. That crisis is no longer abstract or emerging — it is measurable, visible, and urgent. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 40 percent of high school students reported feeling persistently sad or hopeless in 2021, up from 28 percent a decade earlier. Nearly one in five seriously considered suicide. Among girls, the numbers are even more dire: Nearly 60 percent reported persistent sadness or hopelessness, and 30 percent said they had considered suicide. The American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and the Children’s Hospital Association have jointly declared this a national emergency. Schools are at the front lines of this crisis. Yet our default response — more SEL, more trauma awareness, more therapeutic intervention — may be managing the symptoms while reinforcing the cause … In studies published in the Journal of Positive Psychology and other journals, Clifton and co-author Peter Meindl found that negative primal beliefs were strongly associated with anxiety, cynicism, depression, suicidal ideation, and less life satisfaction. By contrast, people with sunnier beliefs — those who saw the world as safe and enticing — tended to report dramatically better outcomes across the board, including greater life satisfaction, more emotional resilience, better physical health, stronger interpersonal relationships, and lower levels of anxiety and depression. The widespread belief that viewing the world as dangerous fosters vigilance and success is, Clifton and Meindl found, unsupported. If you work in education — or have a child in school — you’ve probably encountered the growing emphasis on trauma-informed pedagogy. This approach, born of legitimate concern for children who’ve experienced adversity, encourages teachers to consider trauma as a key explanation for misbehavior or disengagement. In practice, it can lead to lower expectations, less structure, and a default posture of therapeutic intervention rather than academic instruction. Social and emotional learning, too, has evolved far from its original goal of helping children navigate their emotions. In many schools, SEL has become the central organizing principle of classroom culture: “emotional check-ins,” “restorative circles,” “safe spaces,” and constant reminders that children are “not okay” — that they carry trauma, or live in an unjust world, or must always be on guard against microaggressions and existential threats. Summarizing [Clifton’s] work, Arthur Brooks wrote in The Atlantic, “No doubt these beliefs come from the best of intentions. If you want children to be safe (and thus, happy), you should teach them that the world is dangerous — that way, they will be more vigilant and careful. But in fact, teaching them that the world is dangerous is bad for their health, happiness, and success.” … To be clear, none of this is an argument for rose-colored glasses. Children need to know that the world contains hardship, injustice, and danger. But they also need to know that it contains beauty, opportunity, and meaning — and that history contains a record of genuine progress and that further progress remains possible. And only one of those orientations leads reliably to flourishing. As Clifton puts it, “There’s beauty everywhere — we have only to open our eyes to see it.” But someone must show children how.

[Note: I first became aware of the study of primal world beliefs by watching this presentation of the topic hosted by the American Enterprise Institute.]