Continuing this essay series on political trends, this essay explores what some research has to say about the association between partisanship and certain emotional states and mindsets.

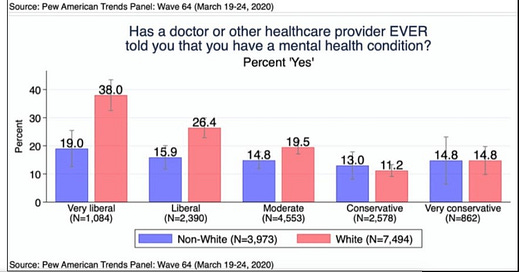

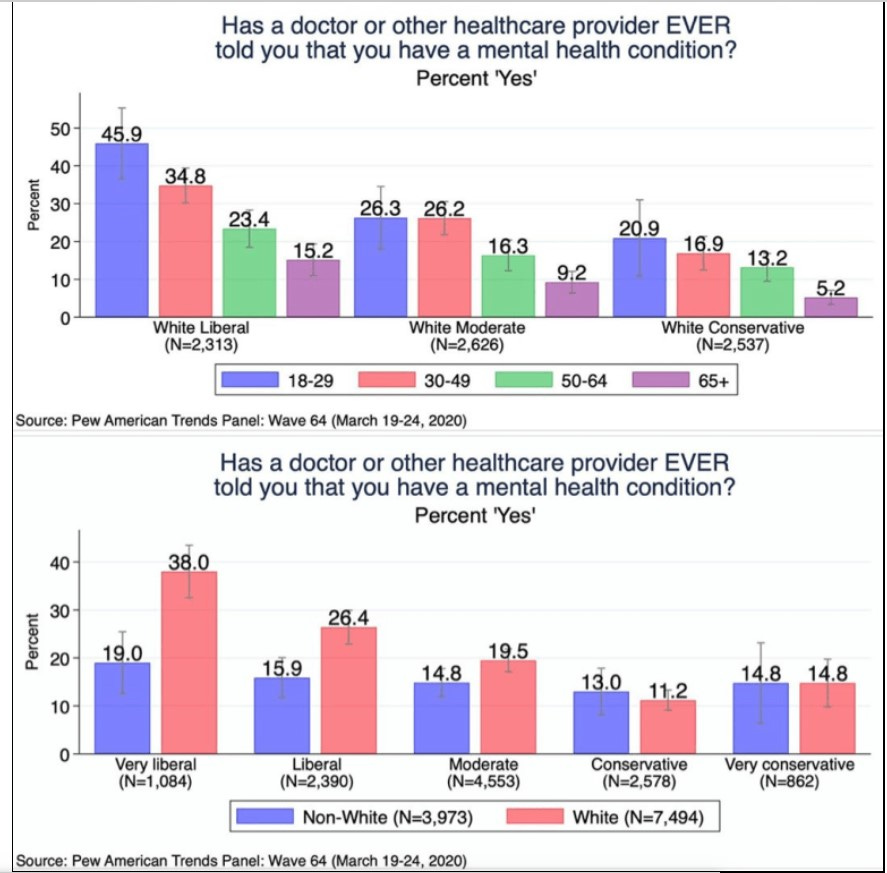

Liberals are more than twice as likely as conservatives to be found to have a mental health condition.

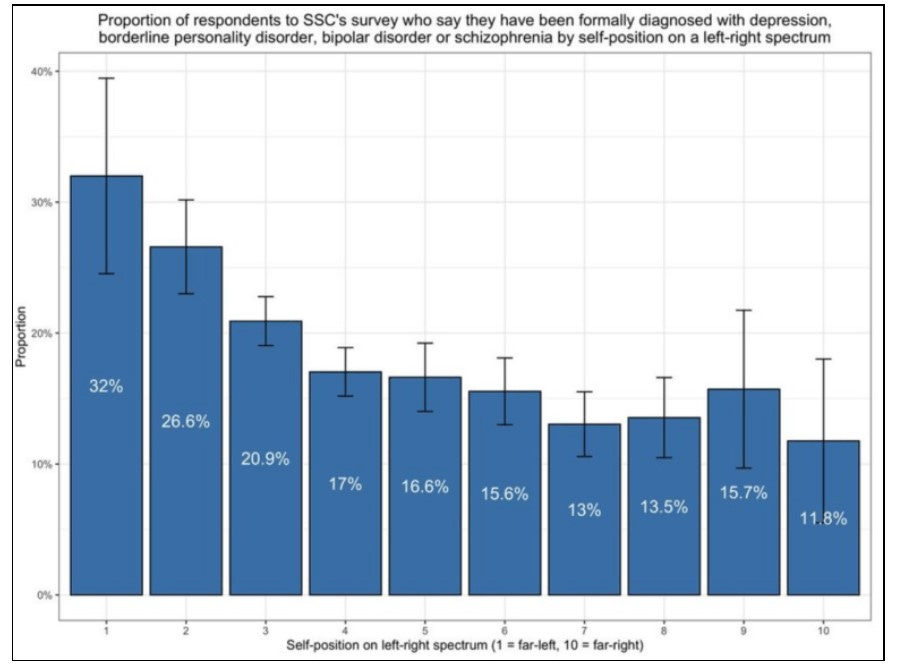

Other research shows as follows:

It has been claimed that left-wingers or liberals (US sense) tend to be more mentally ill than right-wingers or conservatives. This potential link was investigated using the General Social Survey. A search found 5 items measuring one’s own mental illness in different ways (e.g.”Do you have any emotional or mental disability?”). All of these items were associated with left-wing political ideology as measured by self-report. These results held up mostly in regressions that adjusted for age, sex, and race. For the variable with the most data, the difference in mental illness between “extremely liberal” and “extremely conservative” was 0.39 d. This finding is congruent with numerous findings based on related constructs.

Researchers have also found that:

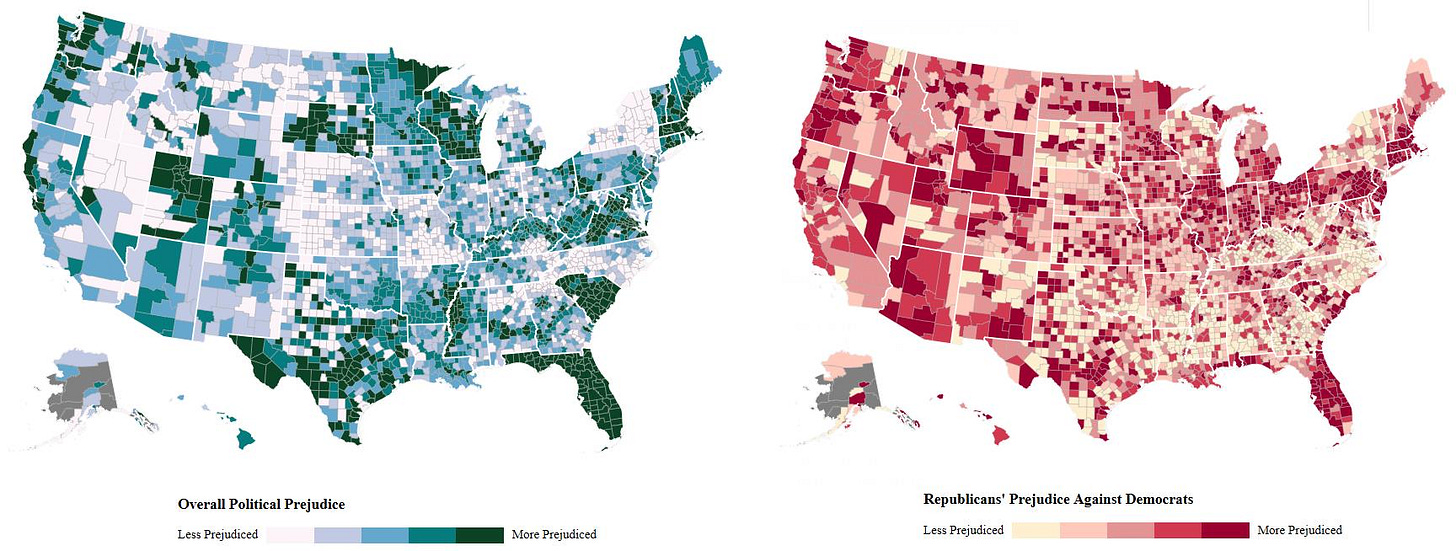

In general, the most politically intolerant Americans, according to [one] analysis, tend to be whiter, more highly educated, older, more urban, and more partisan themselves. This finding aligns in some ways with previous research by the University of Pennsylvania professor Diana Mutz, who has found that white, highly educated people are relatively isolated from political diversity. They don’t routinely talk with people who disagree with them; this isolation makes it easier for them to caricature their ideological opponents. (In fact, people who went to graduate school have the least amount of political disagreement in their lives …).

(In contrast, the most accurate predictors of future effects are those who expose themselves to different viewpoints. For example, the economic forecast of the growth effects of the 2017 federal tax reform law were most accurately predicted by prominent economists on both sides of the political spectrum working together on a consensus forecast.)

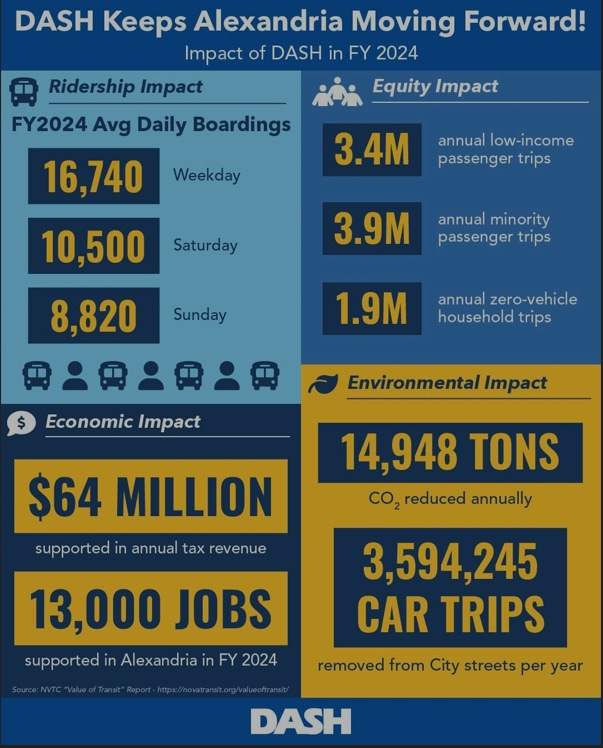

On that subject, in the wake of Donald Trump’s re-election in 2024, millions of left-wing activist users of X (formerly Twitter) left X for a platform called Bluesky, which has been touted as a “refuge” for similarly-minded left-wing activists. Only weeks after the election, the speech norms on Bluesky had devolved such that people making just about any comments that could be remotely considered contrary to the prevailing Bluesky viewpoint were expected to be “blocked.” I dabbled on the platform for a couple days, focusing on the posts of two people who run a left-leaning blog regarding our city of Alexandria, Virginia. One of those people posted the following “infographic” showing various statistics related to the “free” shuttle buses the city runs, at taxpayer expense, which doesn’t charge a fare to help run it, and argued that “math” in the infographic supported the program:

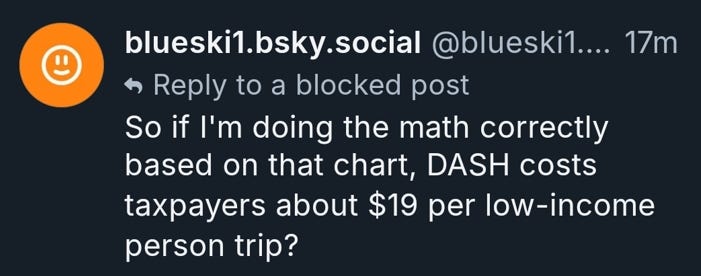

I noticed you could use the chart to easily calculate the cost of the program per low-income rider, and posted the following:

That’s pretty costly, and hard to justify given that a typical local ride on Uber or Lyft costs much less than that. But that response was all it took to get me blocked:

(Incidentally, Mr. O-Connell ran for a spot on our local city council during the last election. He raised more money than any other city council candidate yet failed to place in the top six in order to win a seat, perhaps in part because he refers to George Washington as “our citywide Founding Father circle jerk.”)

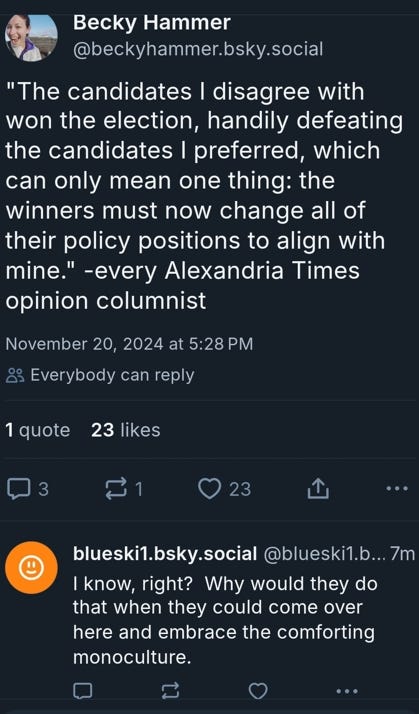

Mr. O’Connell’s co-blogger justified the blocking this way, with my short reply:

That same blogger, by the way, posted this:

My response was sarcastic, sure, but Ms. Hammer’s position was hypocritical: Bluesky had already become a one-sided platform dedicated to posting opposition to various (Republican) winners of the last federal election, but here was a statement on Bluesky implying that people who opposed the positions of the local (Democratic) winners of the local elections should, well, just be quiet.

And then she blocked me for this response to a picture she posted of herself with the local mayor giving the “thumbs up” to an “Antifa Chardonnay.”

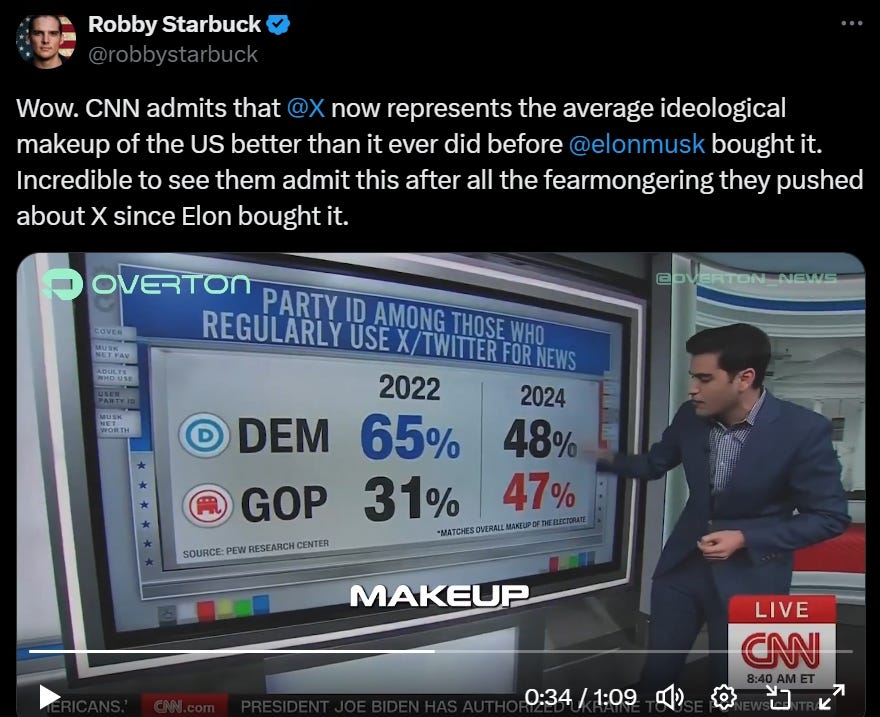

Cultivating a monoculture of one-sided virtue signaling is not the best way to become more attuned to the larger electorate. And, interestingly, X appears to have become much more reflective of the general electorate, especially now that large numbers of left-wing activists (who compose a very small slice of the larger electorate) have left for Bluesky. Here’s an interesting clip from CNN in that regard:

https://x.com/robbystarbuck/status/1858905147738329202

Regarding voting trends based on income, as Nate Moore writes:

For the first time since exit polls began tracking household income, Democrats [in the 2024 presidential election] did better with voters making more than $100,000 than with voters making less than $50,000. Trump, meanwhile, became the first Republican since George H.W. Bush to win voters making less than $50,000. His 2-point win with this group—just about matching his popular-vote margin—marks an 11-point swing from Biden’s 54 percent to 45 percent win four years ago. On the other hand, those making $100k or more (30 percent of the electorate) voted for Biden by 5 points and Harris by 6. A one-point shift to the left seems small, but in the context of a broad national shift to the right, any demographic group that moved towards Democrats is notable. Men shifted right. Women shifted right. Young voters shifted right. White, black, and Hispanic voters shifted right. But the richest voters shifted left … What about highly educated, wealthy black voters? Could this phenomena have nothing to do with race and everything to do with class and education? Not quite. A look at the two wealthiest majority-black counties in the U.S.—Maryland’s Prince George’s and Charles counties—suggests that even these neighborhoods shifted slightly right. Woodmore, which is 80 percent black and has a median household income of $186,000, shifted 3 points towards Trump. Mitchellville, which is 85 percent black and has a median household income over $150,000, shifted 4 points towards Trump. Prince George’s as a whole moved 5.8 points to the right. To be sure, these are more muted swings than many non-white areas. But it is also evidence that Harris could not replicate Obama’s (or Biden’s) margins even with rich, highly educated, black suburbanites—a remarkably favorable demographic combination for Democrats. Nationally, black voters with a college degree shifted from Obama +90 to Biden +79 to Harris +72.

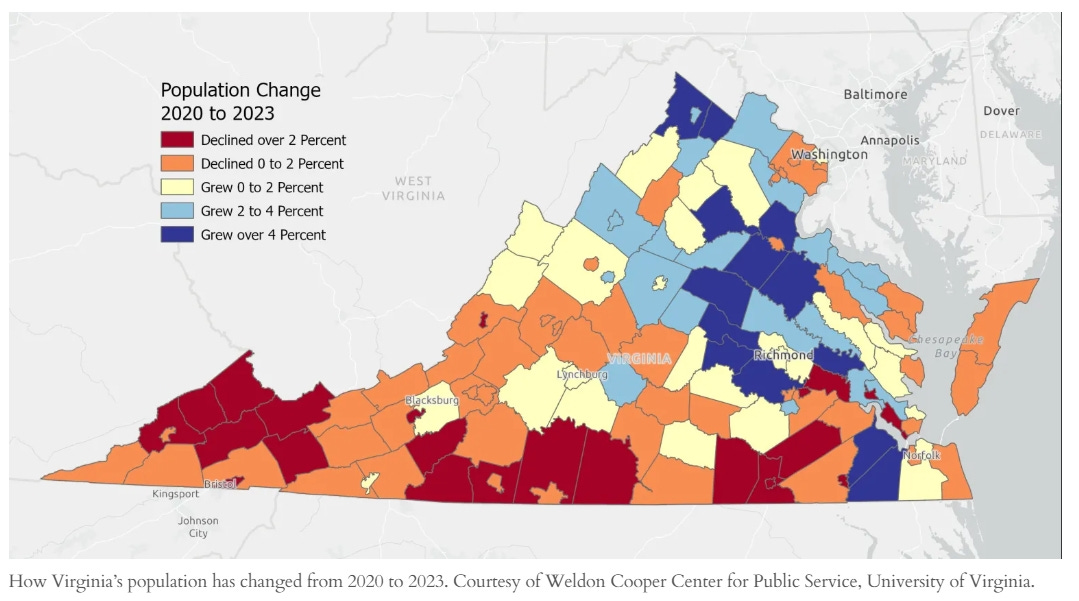

Also, regarding trends over the last couple of decades in my own City of Alexandria, Virginia (a very wealthy area generally: median household income of $113,000, compared to the national median figure of $75,000), the electorate here has consistently elected Democrats for City Council and Mayor. But following that era of one-party control, the City is failing two of the most basic metrics for judging the direction of a polity: its tax base and its population trends. A whopping 82% of Alexandria’s tax base comes from residential property taxes, whereas most localities aim for a close to 50-50 split between residential and commercial sources of revenue. And people are also net migrating out of the Alexandria area and into more rural areas in Virginia:

Also, if Alexandria is anything like D.C., the current city council’s preference for bike lanes over car lanes seems misguided. As was reported in the Washington Post: “The city [DC] has built about 20 miles of bike lanes in the past five years, but despite that, the portion of D.C. residents who bike to work peaked in 2017 and has decreased each year since, falling from 5 percent to 3 percent.”

Anyway, back to national political trends.

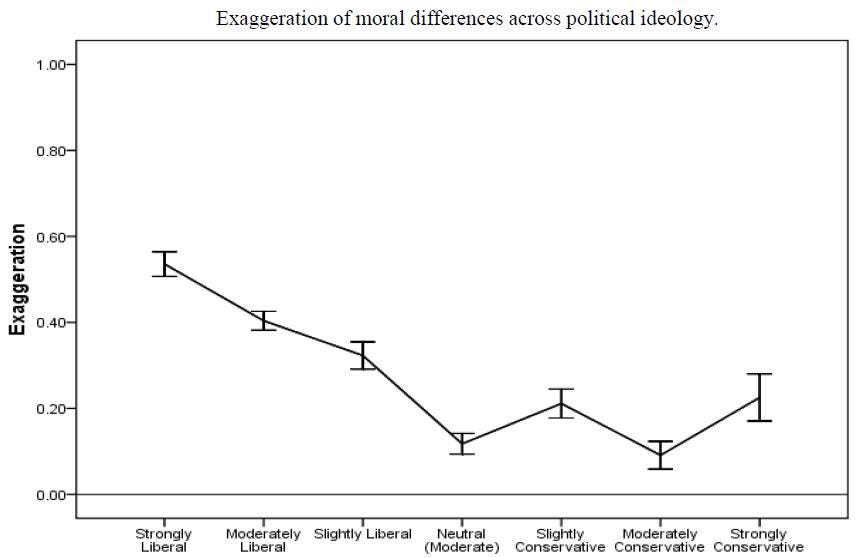

In the United States, researchers have found that while both liberals and conservatives exaggerate the differences in moral sentiments between them, liberals exaggerate such differences the most, and “moderate conservatives” exaggerate such differences the least.

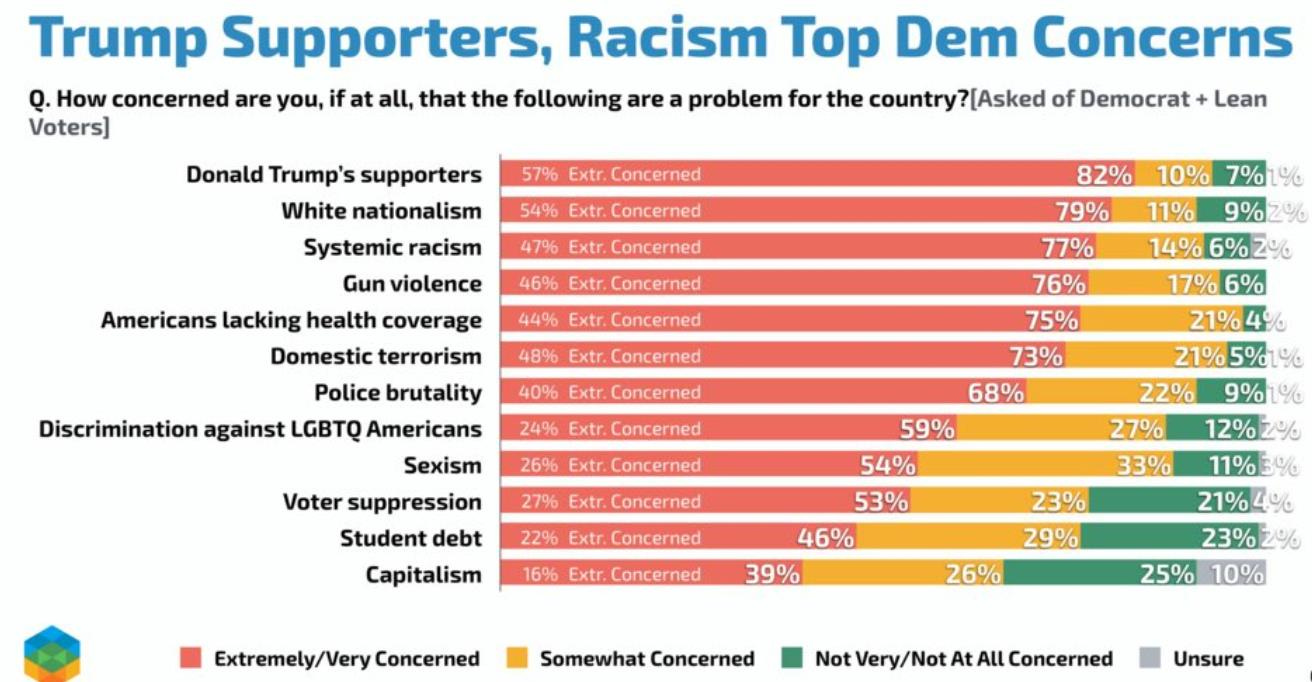

Consonant with that finding, a poll released in February, 2021, by Echelon Insights, found that Democrats ranked “Donald Trump’s supporters” as the largest problem the country faces.

Female candidates tend to communicate more angry emotions on social media. As researchers have found:

We find that women, most notably Democratic candidates, are more likely to convey angry emotions on Twitter, not only matching male colleagues but defying gendered social stereotypes to turn frustration into a valuable political asset. Across the four last congressional elections, women have averaged more angry words in their digital appeals, with that anger as a consistent facet of how women engage online. Women are leaning into angry emotional appeals and adopting a negative appeal in their digital engagement that highlights their policy and political frustrations for voters.

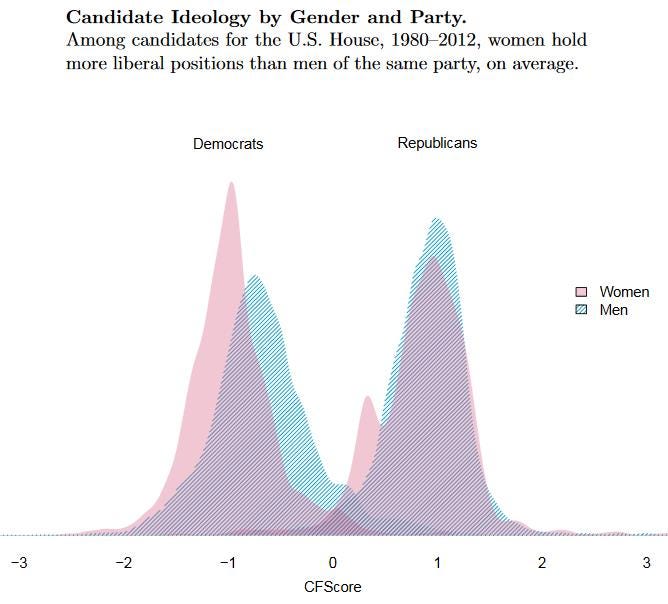

Among candidates for the U.S. House, women also generally hold more liberal positions than men of the same party.

Other researchers have found that “Analyzing changes within districts over time, we find that congresswomen secure roughly 9% more spending from federal discretionary programs than congressmen.” The Report of the Advisory Committee on Research on Women’s Health also found that in almost every category there is more female-focused NIH funding than male-focused NIH spending with the totals more than two to one in favor of females ($4.5 billion to $1.5 billion). The report also found that enrollment of women in all NIH-funded clinical research in 2015 and 2016 was 50 percent or greater; in the most clinically-relevant phase III trials, the proportion of female participants enrolled in NIH-defined Phase III Clinical Trial was 67 percent in 2015 and 66 percent in 2016. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services also found that per capita health spending for females was $8,315 in 2012, approximately 23 percent more than for males, $6,788.

As Keith Stanovich writes in his book The Bias That Divides Us: The Science and Politics of Myside Thinking, ideological “conservatives” do not tend to resist change per se; rather, they tend to support the preservation of existing norms and systems which they believe are beneficial in the face of contemporary attacks on those systems. As Stanovich writes:

A study by Jutta Proch, Julia Elad-Strenger, and Thomas Kessler (2019) demonstrates how researchers can too quickly jump to the conclusion that they are measuring a general psychological characteristic when they have not sampled content broadly enough. Their 2019 study challenges the long-standing view in the psychological literature that political conservatism is associated with resistance to change. Proch, Elad-Strenger, and Kessler (2019) point out that a person’s stance toward change may not be a function of change per se, but rather of how the person views the current status quo. People who approve of the status quo tend not to want to change it, whereas those who do not approve tend to favor change. Proch, Elad-Strenger, and Kessler (2019) found no general tendency for conservative subjects to be more resistant to change than liberal subjects were. The results of their study pretty much confirm the commonsense conclusion that both political groups approve of the status quo when it matches their sociopolitical worldview and both disapprove of change when it moves the status quo away from that worldview.

Stanovich also describes the research dispelling the false notion that intolerance is uniquely associated with conservative ideology, low intelligence, and low openness to experience. As he writes:

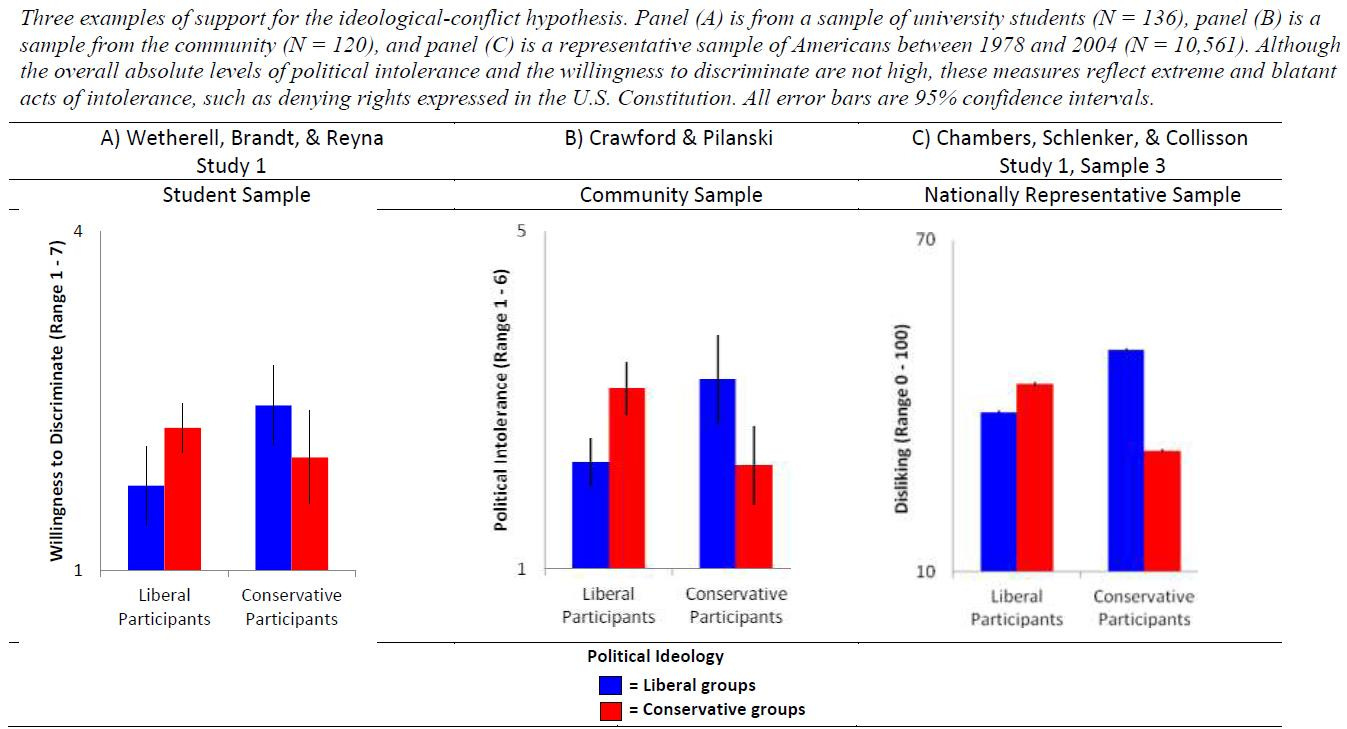

Expanding the range of the stimuli used in research has been critical in the recent reconsideration of earlier social psychology research on prejudice, intolerance, and warmth of feelings toward various social groups (Crawford 2018), although concern about this earlier research goes back at least to the work of Philip Tetlock (1986; see also Ray 1983, 1989). It was long thought that out-group prejudice and intolerance were associated with conservative ideology, low intelligence, and low openness to experience. Proponents of the “ideological conflict hypothesis” (Brandt et al. 2014; Chambers, Schlenker, and Collisson 2013) questioned the generality of these earlier findings by pointing out that the target social groups in these studies (African Americans, LGBT people, Hispanics) were often groups who shared ideological affinity with liberals and whose values conflicted with those of conservatives. Thus the lower out-group warmth and tolerance shown by conservative subjects may well have been due to an ideological conflict with the target groups used in the earlier studies. In a test of this hypothesis, John Chambers, Barry Schlenker, and Brian Collisson (2013) demonstrated how earlier studies of the relationship between conservatism and prejudice had confounded the target groups with ideology. The target groups in most of the classic experiments on prejudice were groups known to share liberal values, so when subjects had to indicate warmth toward a particular group or indicate that they would treat its members with tolerance, conservative subjects were faced with a conflict—the values of the group they had to evaluate were known to conflict with conservative values. Liberal subjects were faced with no such conflict—they were simply asked to indicate the degree of tolerance they would show target groups whose members believed exactly as they did.1 When, however, Chambers, Schlenker, and Collisson (2013) measured the degree of tolerance and warmth liberal subjects displayed toward groups whose values conflicted with liberal values (businesspeople, Christian fundamentalists, the wealthy, the military), they found that liberal subjects displayed as much out-group dislike as conservative subjects did … Many empirical studies have put the ideological conflict hypothesis to the test. The results of these studies have converged on the conclusion that measures of out-group tolerance, prejudice, and warmth are more a function of the degree to which the values of subjects match or conflict with the values of the target groups than of the psychological characteristics of the subjects. Correlations of intolerance and lack of warmth with conservatism, low intelligence, or openness virtually disappear once social groups of a more diverse range are included in the rating tasks. It seems that liberal subjects can also display intolerance—but just toward groups who do not share their worldviews or values (businesspeople, Christian fundamentalists, the wealthy, the military) … Riley Carney and Ryan Enos (2019) have demonstrated how specific content plays a role in determining responses on the much-used modern racism scales (Henry and Sears 2002). These scales are particularly prominent in attempts to link racism with conservative opinions. Typical are propositions like “Irish, Italian, Jewish, and many other minorities overcame prejudice and worked their way up; blacks should do the same without any special favors” or “It’s really a matter of some people not trying hard enough; if blacks would only try harder, they could be just as well off as whites.” Carney and Enos (2019) ran several experiments in which they inserted other groups in the slot for the usual target group, African Americans (often termed “blacks” in such scale items to focus subjects specifically on race). In different experimental conditions, they inserted as target groups Taiwanese, Hispanics, Jordanians, Albanians, Angolans, Uruguayans, and Maltese. Their startling conclusion was that, even though conservative subjects endorsed all of the propositions on the scale more strongly than liberal subjects did, they endorsed them regardless of the target group, whereas liberal subjects were less likely to endorse the propositions on the scale when the target group was African Americans (Carney and Enos 2019). Carney and Enos (2019) further concluded that these modern racism scales captured not racial resentment specifically connected to conservatives, but instead racial sympathy specifically connected to liberals (see also al Gharbi 2018; Edsall 2018; Goldberg 2019; Uhlmann et al. 2009). For conservative subjects, the so-called modern racism scales served to measure not their racism but instead their belief in the relative fairness of current society in rewarding effort; and, as such, these scales have been mislabeled from their very inception. For liberal subjects, the scales did serve to measure something specifically directed at blacks, but that something, if anything, was liberal subjects’ tendency to display a special affinity toward African Americans—or perhaps their awareness that African Americans were the target group with the highest payoff in terms of virtue signaling.

Stanovich then discusses how psychological research regarding conservative ideology in universities was tainted by “myside bias” – which he defines as “occur[ring] when we search for and interpret evidence in a manner that tends to favor the hypothesis we want to be true.” Stanovich writes:

[T]he myside bias blind spot in the academy is a recipe for disaster when it comes to studying the psychology of political opponents. Nowhere has this been more apparent than in the relentless attempts by academics to demonstrate that political opponents of liberal ideas are somehow cognitively deficient. In the years since 2003, it has not been hard to find studies showing correlations between conservatism and intolerance, prejudice, low intelligence, close-minded thinking styles, and just about any other undesirable cognitive or personality characteristic. The problem is that most of these relationships have not held up when subjected to critiques emanating from ideological framings different from most of the earlier research. These correlations were grossly attenuated or they disappeared entirely when important features of the research framing were changed (see Reyna 2018). For example, the 2013 study by John Chambers, Barry Schlenker, and Brian Collisson … demonstrated that out-group tolerance, prejudice, and warmth are more a function of the degree to which the values of the target group match or conflict with the values of subjects than a function of the subjects’ ideology. In a follow-up study examining the responses of a representative sample of nearly 5,000 Americans, Mark Brandt (2017) showed that the perceived ideology of the target group was the main predictor of the relationship between ideology and prejudice. Liberal ideology was positively correlated with favorable attitudes toward LGBT people, atheists, immigrants, and women, but negatively correlated with attitudes toward Christians, rich people, men, and white people. Thus prejudice occurs on both sides of the ideological divide, but it tends to be directed toward different target groups What all of these findings show is that neither liberals nor conservatives are intolerant or prejudiced in general. They are instead “culturist,” to use Yuval Noah Harari’s (2018) term—they support or oppose target groups depending upon whether they share cultural values with the groups in question … Even endorsing the view that hard work leads to success for many people in America will get subjects a higher score on a “symbolic racism” scale (Carney and Enos 2019; Reyna 2018). In such studies, the overt ideological bias of psychologists is blatantly obvious to any neutral observer. The clear purpose of such studies seems to be to label anyone who does not adhere to liberal orthodoxy as a “racist.” Jason Weeden and Robert Kurzban (2014) call this tendency to embed in a new scale items that assess the very concept that the researchers want to correlate with the new scale the “Direct Explanation Renaming Psychology (DERP) syndrome.” The syndrome is ubiquitous in racism research. Psychologists want to investigate whether conservatism is associated with racism because, in actuality, they think that it is. First, they construct racism scale items that reflect conservative worldviews (“Anyone can get ahead in America if they work hard”; “Discrimination against African Americans in the United States is much less than it once was”; and so on). Then, they correlate this scale with a measure of self-reported liberalism or conservatism and, lo and behold, there is a correlation in the direction they expected. Basically, they have correlated a scale containing, in part, conservative beliefs, called the conservative beliefs “racist,” and then reported as an empirical finding that conservatism correlates with racism—a perfect example of the DERP syndrome. For more than two decades now, the items in so-called sexism scales have undergone such “concept creep” (Haslam 2016) in their attempt to label normal male behavior as psychologically damaging. There is now a form of sexism (called “benevolent sexism”) that increases subjects’ sexism scores if they endorse items affirming that women should be cherished and protected by men; that a man is not complete without a woman; that women should be rescued first in a disaster; that women are more refined than men; that women have a special moral sensibility; and that men should sacrifice in order to provide financially for the women in their lives (Glick and Fiske 1996). Someone would have to be entirely enveloped within the insular academic bubble not to see such studies as ideology masquerading as science. Indeed, the female subjects in these experiments disagree with the conceptual definitions of the authors of the studies. These experiments consistently find that women subjects do not view men who endorse these items as prejudiced against women (Gul and Kupfer 2019), and also that they view men who endorse such items as more “likable” and more “attractive.”

So generally, researchers have found that both liberals and conservatives express intolerance toward groups generally associated with holding ideological views contrary to their own, and that it is generally the ideological views of the subject, not the race or other factors, that is the source of the intolerance.

Stanovich also describes how values, not knowledge, can influence policy preferences. As he writes:

[P]olitical scientist Arthur Lupia (2016, 116) calls the “error of transforming value differences into ignorance”—that is, mistaking a dispute about legitimate differences in the weighting of the values relevant to an issue for one in which your opponents “just don’t know the facts.” Years ago, in an elegant essay, Dan Kahan (2003) argued that this was exactly what had happened in the debate over gun control, which had been characterized by the “tyranny of econometrics”—arguments centered on “what studies show” in terms of lives saved by the use of weapons in self-defense, deterrence of crime, and the risk factor of having a gun in the home. Kahan (2003) further argued that the central issue would never be resolved nor would compromises ever be reached by mutual agreement on what the facts were because at the center of the debate was culture: what kind of society Americans wanted to have. Gun control proponents were swayed by the value they put on nonaggression and mutual safety enforced by the government. Gun control opponents were swayed by the value they put on individual self-sufficiency and the individual right of self-defense. These values tracked urban versus rural demographics (among others), and the weighting of these values by a particular individual in either of the opposing groups was not going to be much affected by evidence, if at all … [O]ther problems on this list—such as climate change, pollution, terrorism, income inequality, and a divided society—are of an altogether different kind from poverty and violence. For some of these, we may be looking not at problems we would expect to solve with greater intelligence, rationality, or knowledge, but rather at problems that arise from conflicting values in a society with diverse worldviews. For example, reducing pollution and curbing global warming often require measures that entail, as a side effect, restraining economic growth. The taxes and regulatory controls necessary to markedly reduce pollution and global warming often fall disproportionately on the poor … Likewise, there is no way to minimize global warming and maximize economic output (hence jobs and prosperity) at the same time. People differ on their “parameter settings” for trading off environmental protection against economic growth, but they do so not because some of them lack knowledge and others don’t. Instead they differ because they hold different worldviews … Samara Klar (2013), for example, found that Democratic voters, normally very supportive of reduced sentences for criminals, including sex offenders; of decreased spending on antiterrorism; and of increased spending on social services became less supportive of all three positions when reminded of the values they attached to their roles as parents. Awareness of their deeply felt need to protect their children and the future world their children would inhabit had the effect of making these Democratic voters less sympathetic to criminals and more concerned both with future terrorism and with budget deficits. Reminding them of their parental roles made them aware that conflicts in their values entailed trade-offs in their positions on these issues. Unfortunately, politics as normally practiced operates under conditions totally unlike those set up in Klar’s 2013 study. Politicians and political partisans present issues to us as if they entailed no value trade-offs. They imply that only one value is at stake and if we hold onto that value and take the most partisan position, then nothing is lost on other issues that we might care about. Because this is a fallacy embraced by both sides in our ideologically divided electorate, we could encourage less mysided political discussion by recognizing and exposing it as a cognitive trick that is being played on all of us.

(Regarding stereotypes generally, a meta-analysis of research on stereotypes and their accuracy found that “Our review has shown … that it is unusual (but not unheard of) for stereotypes to be highly discrepant from reality, that the correlations of stereotypes with criteria are among the largest effects in all of social psychology, that people rarely rely on stereotypes when judging individuals, and that, sometimes, even when they do rely on stereotypes, it increases rather than reduces their accuracy.”)

Also, regarding ideological associations with general knowledge, one analysis of General Social Survey results found that:

The best evidence we have suggests that, compared to the general public, Trump supporters score significantly better than the rest of the public—and Clinton supporters score significantly worse—on a standard verbal ability test. Likewise, Trump supporters score significantly better on most science knowledge questions than Clinton supporters or the general public. In this essay, I analyzed the results of over 30 questions from 22 different representative national surveys, involving over 20,000 respondents. Not one of the questions I examined here supports the idea that Trump supporters are significantly less knowledgeable than Clinton supporters, and some of them point to small or moderate differences in the opposite direction.

As reported by Holman Jenkins, Jr.:

A study last year of the 2016 election by six scholars affiliated with Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center … found that social media “engagement” that shaped the election outcome overwhelmingly was sparked by the traditional profit-seeking, left-tilting national media, plus new-style, right-wing outlets like Breitbart -- and not by fake news sites or Russian bots.’“The ‘fake news’ framing of what happened in the 2016 campaign … is a distraction,” says the study. The real difference maker in 2016 was the rise of highly propagandistic, dissenting, right-wing media, but the authors are far from certain that its arrival should be considered an ‘attack on democracy, rather than its expression.’ … As a separate study in the Columbia Journalism Review also notes, ‘engagement’ with fake news often has more to do with its ‘entertainment value’ than its believability. Dartmouth College’s Brendan Nyhan, another debunker of the fake-news hysteria, points out what anybody in charge of spending ad dollars already knows: People just aren’t that influenceable. Even if fake news were as effective as TV advertising, concludes yet another careful study, ‘the fake news in our database would have changed vote shares by an amount on the order of hundredths of a percentage point.’”

And as Stanovich writes in The Bias That Divides Us:

Research using more balanced items has suggested that conspiracy beliefs are equally prevalent on both the political right and the political left (Enders 2019; Oliver and Wood 2014) … In summary, both in terms of what knowledge is acquired and how that knowledge is acquired, there is no strong evidence that the Trump voters were more epistemically irrational than the Clinton voters were.

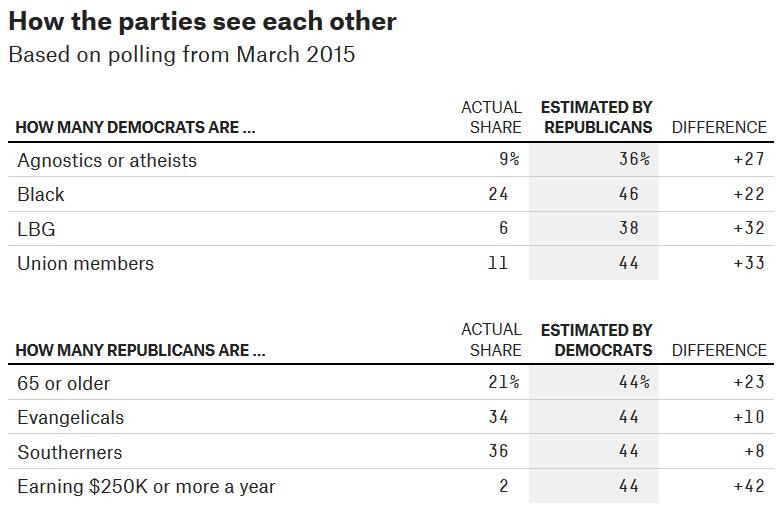

Surveys also show that voters affiliated with a particular political party often greatly overestimate the percentage of certain demographic groups among those affiliated with the opposing political party, but the most extreme example of such appears to be Democrats’ 42 percentage point overestimation of the percentage of Republicans who earn more that $250,000 a year.

And regarding general science knowledge, as Stanovich writes in The Bias That Divides Us:

Some years ago, this type of thinking prompted the Democratic Party to declare itself the “party of science” and to label the Republican Party as the “party of science deniers.” In fact, it is not hard to find scientific issues on which it is liberal Democrats who fail to accept the scientific consensus. There are enough examples to produce a book parallel to Mooney’s The Republican War on Science—one titled Science Left Behind: Feel-Good Fallacies and the Rise of the Anti-Scientific Left (Berezow and Campbell 2012). To mention an example from my own field of psychology: liberals tend to deny the overwhelming consensus in psychological science that intelligence is moderately heritable and that there is no strong evidence that intelligence tests are biased against minority groups (Deary 2013; Haier 2016; Plomin et al. 2016; Rindermann, Becker, and Coyle 2020; Warne, Astle, and Hill 2018). Liberals become the “science deniers” in this case. Intelligence is not the only area of liberal science denial, though. In the area of economics, liberals are very reluctant to accept the consensus view that, when proper controls for occupational choice and work history are made, women do not make 23 percent less than men for doing the same work (Bertrand, Goldin, and Katz 2010; Black et al. 2008; CONSAD Research Corporation 2009; Kolesnikova and Liu 2011; O’Neill and O’Neill 2012; Solberg and Laughlin 1995). Just as conservatives tend to deny or obfuscate the research indicating the role of human activities in global warming, so liberals tend to deny or obfuscate the research indicating the greater incidence of behavioral problems among children in single-parent households (Chetty et al. 2014; McLanahan, Tach, and Schneider 2013; Murray 2012). Overwhelmingly, liberal university schools of education deny the strong scientific consensus that phonics-based reading instruction helps most readers, especially those who are struggling the most (Seidenberg 2017; Stanovich 2000). Many liberals find it hard to believe that the scientific consensus is that there is no strong evidence of bias in the hiring, promotion, and evaluation of women in STEM and other disciplines in universities (Jussim 2017a; Madison and Fahlman 2020; Williams and Ceci 2015). Liberal gender feminists routinely deny biological facts about sex differences (Baron-Cohen 2003; Buss and Schmitt 2011; Pinker 2002, 2008). In largely Democratic cities and university towns, people find it hard to believe that there is a strong consensus among economists that rent control causes housing shortages and a diminution in the quality of housing (Klein and Buturovic 2011). I will stop here because the point is made. There is plenty of science denial on the Democratic side to balance the science denial of Republicans with regard to climate change and evolutionary theory. Neither political party is the “party of science” or the “party of science deniers.” Each side of the ideological divide finds it hard to accept scientific evidence that runs counter to its own ideological beliefs and policies. This is consistent with the Peter Ditto and colleagues (2019a) meta-analysis finding of equal partisan myside bias.

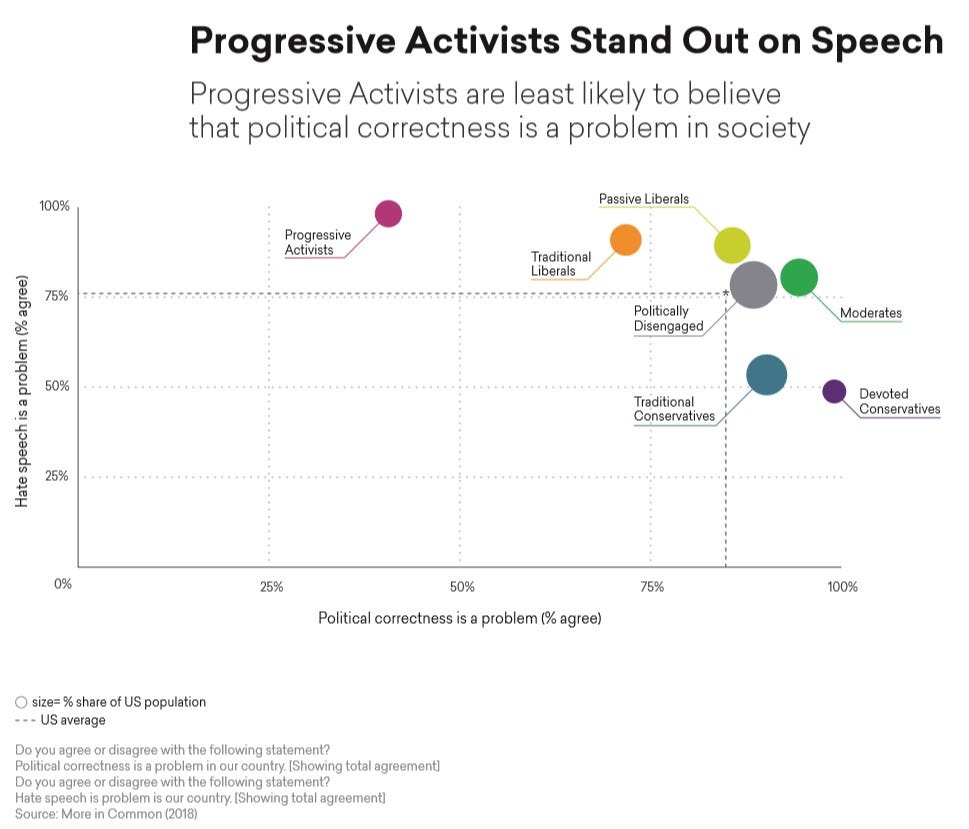

Progressive activists are also unique in that they are much less likely than all other political orientations to believe “political correctness” is a problem in society.

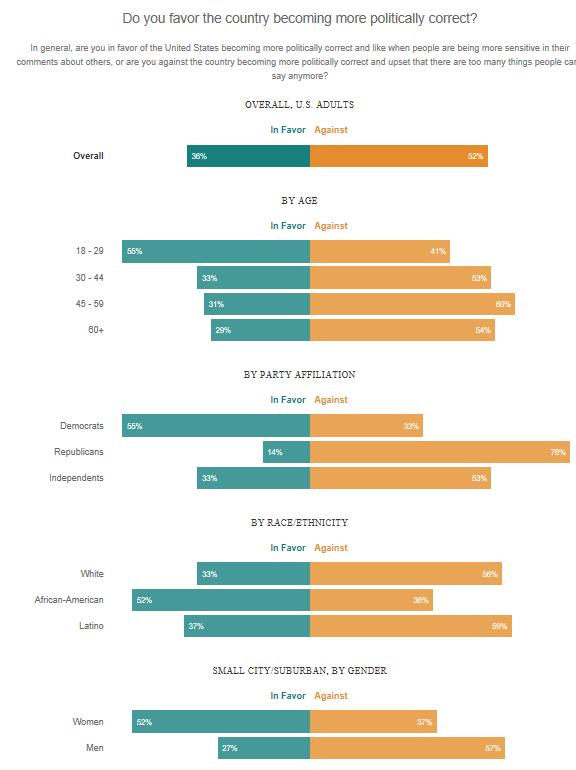

A 2018 National Public Radio survey shows majority opposition to “political correctness” generally, with varying opposition among surveyed subgroups.

Findings from three separate studies also link a person’s political ideology and their self-control performance, with conservatives demonstrating greater self-control than liberals. In each study, participants who identified as politically conservative consistently showed greater attention regulation and task persistence (hallmark indicators of self-control) and these effects were independent of participants’ gender, race, age, education or income.

And while people of a more conservative worldview exercise greater self-control, they also exhibit a greater propensity for risk-taking. An interesting interactive chart showing the political affiliations of various professions (based on political contribution patterns) can be found here, with riskier professions tending to be disproportionately composed of registered Republicans.

A 2018 American Institutional Confidence Poll, sponsored by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation and Georgetown University’s Baker Center for Leadership & Governance, measured trust in various institutions among Republicans and Democrats. It found the biggest partisan gaps are for the executive branch, religion, banks, major companies and local police (more liked by Republicans) versus universities, the press, organized labor, Google and Amazon (more liked by Democrats).

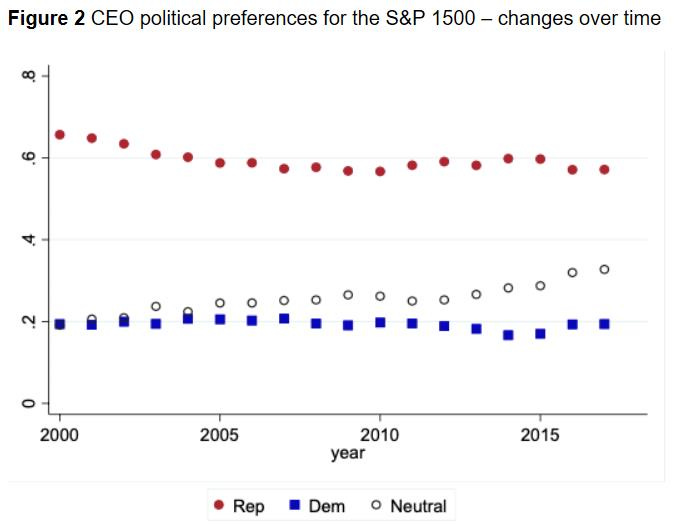

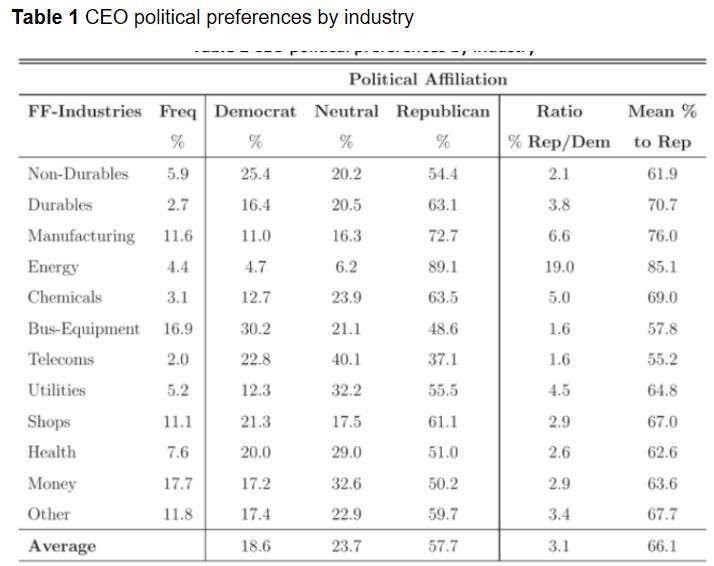

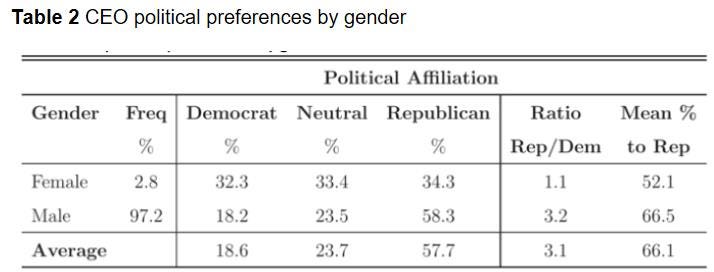

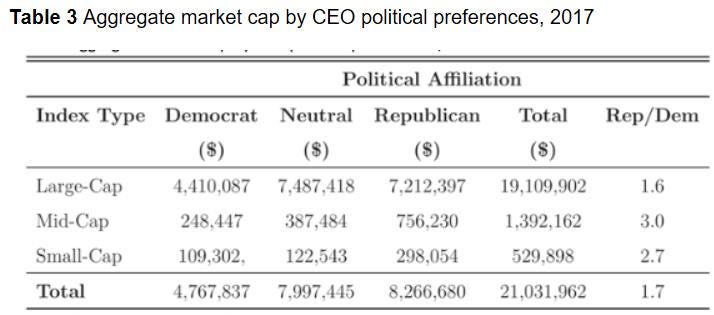

CEO’s, especially those working in manufacturing and energy, and small cap companies, generally prefer Republican candidates. Female CEO’s support Republicans as much as Democrats.

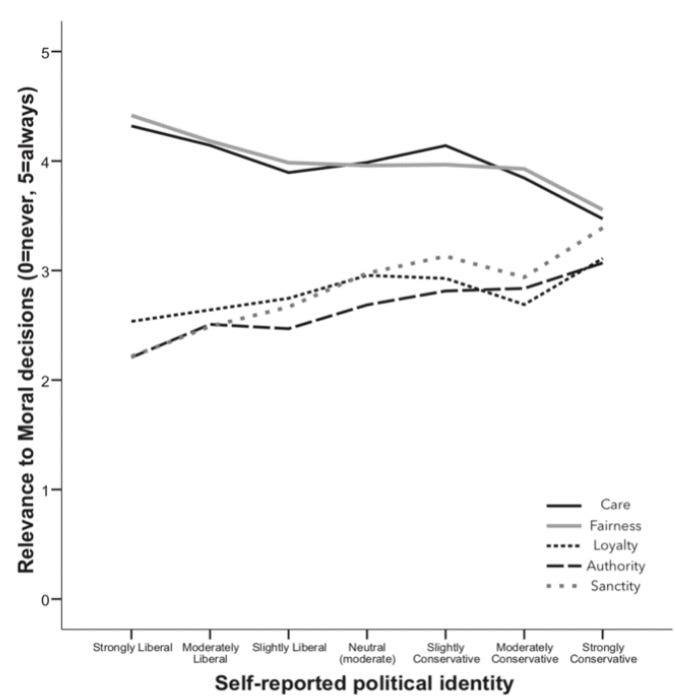

Psychology professor Jonathan Haidt and fellow researchers have surveyed the commonalities in moral sentiments as they have evolved over time among cultures worldwide and divided them into a handful of categories. Their research has shown that certain political perspectives -- particularly “conservatism” -- correlate better with all of these fundamental moral foundations by giving them closer to equal weight.

A large survey of Americans of different political orientations also shows that the views of liberals and especially progressive activists, unlike those of other political orientations, generally do not correlate with all aspects of these moral foundations.

Finally, other researchers found that “Democrats display more dislike towards Republicans than Republicans do towards Democrats. In the favorability measurement, for example, the coefficient for Democrats' dislike of Republicans (−.673) was nearly twice that of Republicans' dislike of Democrats (−.360).”

In the next essay in this series, we’ll explore ideological associations between marriage and fertility.