This essay continues a series on voting patterns in the United States over the past several presidential elections.

Among younger people, by 2020 millennials appeared to have increasingly radical views regarding the wholesale replacement of American traditions, based on a failure to perceive historical complexities. As Professor Eric Kaufmann has written, regarding protests in America in 2020:

While 57 percent of Americans disagree with the protestors’ radical slogan, “defund the police,” an astounding 29 percent support it. This is so despite the deaths of a number of black people during the riots and the fact the riots have coincided with a steep rise in the number of black homicide deaths in inner-city neighbourhoods due to a “Ferguson Effect” of police reducing their presence in these areas … Once “harm”, “racism” and other concepts become unmoored from reality, more of the world is remade. Statues which were long ignored become offensive. Complex historical figures like Jefferson or Churchill, who embodied the prejudices of their time, or elites like Columbus or Ulysses Grant, whose achievements had both positive and negative effects, are viewed through a totalizing Maoist lens which collapses shades of grey into black and white. If a historic personage transgressed left-modernist sacred values, their positives instantly evaporate and activists myopically focus on their transgressions. Suddenly, an entire Orwellian world opens up: place names, history books, statues, buildings. When you’re equipped with the anti-racist hammer, everything begins to look like a nail. In this brave new world, it doesn’t matter whether a symbol like the Rhodes Scholarship has acquired a completely different meaning, or whether a statue has become a symbol of something completely different. All must be levelled to bring forth utopia. What has occurred across the West, especially in the English-speaking world, is a steady left-modernist march through the institutions. Beginning in the 1960s, former radicals entered universities and the media, capturing the meaning-producing machines of society. Once boomers became the establishment in the 1990s, the ethos of institutions started to shift. For good and ill, equality and diversity rose up the priority list. As these ideas filtered through Schools of Education and into the K-12 curriculum, older ideas of patriotism faded and the new critical theory perspective began to replace it. Sixty three percent of millennials (aged 22–37) now agree that “America is a racist country,” nearly half say it is “more racist than other countries” and 60 percent that it is a sexist country. Older generations are less radical, but 40–50 percent of boomers and Gen Xers agree with these statements, reflecting the long march of the New Left through American culture. In order to find out how willing liberal Americans are to jettison the country’s cultural identity, I decided, on May 7th, to ask what I thought were outlandish questions—almost to the point of inflicting a Sokal Squared-style hoax on survey respondents. The answers I received amazed me. I then repeated the exercise on June 15th, after the George Floyd killing and subsequent protests to see whether things had gotten even crazier. It turns out they have.

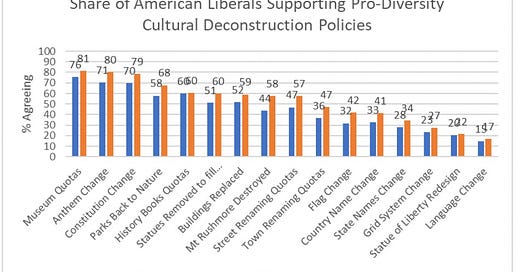

After the preface, “To what extent do you think that the following should be done to address structural barriers to race and gender equality in America,” I presented 16 statements that an amalgamated sample of 870 American respondents could agree or disagree with. The sample is not representative of the American population—I used the Amazon Mechanical Turk and Prolific Academic survey platforms that thousands of academics use. Respondents on these platforms lean young, liberal, and white. But as this is precisely the group I wished to study, this is not a major limitation. Indeed, I have removed conservatives and centrists to focus only on liberals. Liberals are defined as those who rate themselves as a one “very liberal” or two “liberal” on a five-point scale from “very liberal” to “very conservative.” The liberal sample, consisting of 414 people, was 86 percent white and 53 percent male. Forty percent of liberals identified as “very liberal” and the other 60 percent as just “liberal.” Responses ranged on a seven-point scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” I’ve simplified the seven categories into a binary agree-versus-disagree score. Those who scored a four—“neither agree nor disagree”—were dropped from the analysis, permitting me to gauge where the balance of committed opinion lies. Here is what I asked people to agree or disagree with:

1. Rebalance the history taught in schools until its voices and subjects reflect the demographics of the population and heritage of Native people and citizens of color

2. Move, after public consultation, to a new American anthem that better reflects our diversity as a people

3. Rename our cities and towns until they match the demographics of the population

4. Rebalance the art shown in museums across the country until an analysis of content shows that it reflects the demography of the population and perspective of Native people and citizens of color

5. Move, after an open public process, to a new name for our country that better reflects the contributions of Native Americans and our diversity as a people

6. Rename our states until they better reflect the heritage of Native people and citizens of color

7. Gradually replace many older public buildings with new structures that don’t perpetuate a Eurocentric order, until a more representative public space is achieved

8. Respectfully remove the monument to four white male presidents at Mount Rushmore, as they presided over the conquest of Native people and repression of women and minorities

9. Allow our public parks to return to their natural state, before a European sense of order was imposed upon them

10. Move, after public consultation, to a new American flag that better reflects our diversity as a people

11. Consider adopting a new national language, that will be forged from the immigrant and Native linguistic diversity of this country’s past

12. Remove existing statues of white men from public spaces until the stock of statues matches the demographics of the population

13. Gently remodel the statue of liberty to make it better reflect the diversity of America

14. Rename our streets and neighbourhoods until they match the demographics of the population

15. Move, after public consultation, to a new American constitution that better reflects our diversity as a people

16. Begin changing the layout of our cities, towns, and highways, moving away from the grid system to follow the more natural trails originally used by Native people

Every one of these proposals represents a radical blow to American cultural nationhood. Yet figure 1 shows that six of them carry the support of more than 50 percent of committed liberals—that is, all liberals who did not answer “neither agree nor disagree” to a statement. Eight are backed by a majority of the 40 percent of liberals who identify as “very liberal.” Some 80 percent of those who have made up their mind would replace the national anthem and constitution. With the shifts in opinion we have seen in the past decade, and in the aftermath of the Black Lives Matter protests, the views of these leftists are a good bellwether of where things are headed …

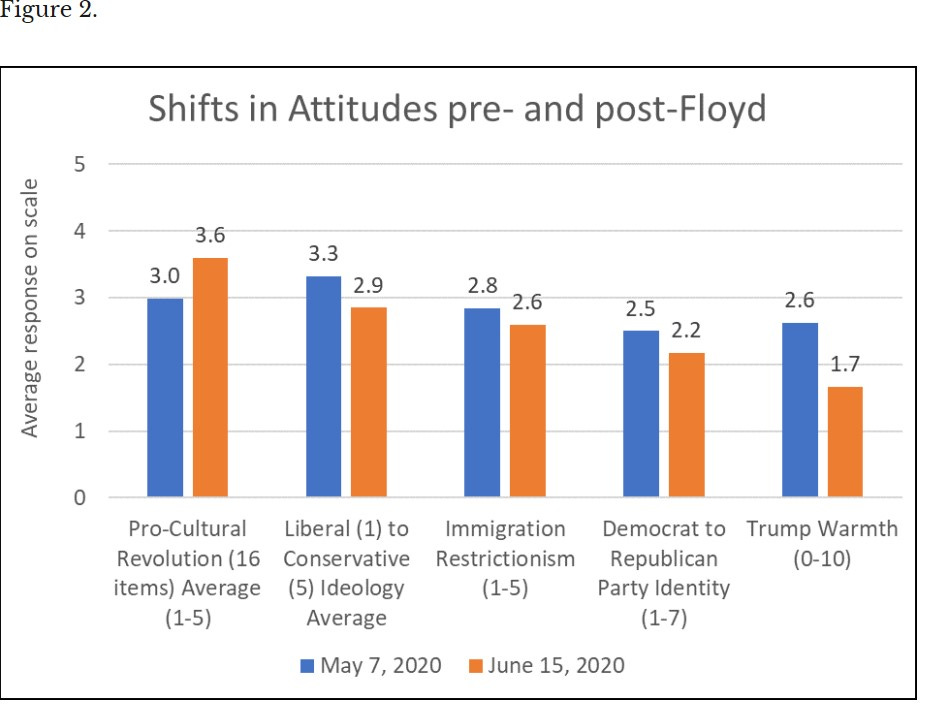

Black Lives Matter protests have stepped up the tempo, supplying oxygen to the cultural revolution. I just happened to run this survey a few weeks before the protests, so felt that it would be opportune to dip my thermometer into public opinion in the wake of them. Using the same survey platform to minimize differences and expand question range, and adding in conservatives, centrists and the undecided, produces the pattern in figure 2. Note that this time, 99 percent of respondents are white. As it shows, support for the 16 cultural revolution questions on a five-point “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” scale rose from an average of three to 3.6, equivalent to a shift between an average response of “neither agree nor disagree” to one leaning towards “agree.” Along the way, people after Floyd’s death were a half-point more liberal on a one-to-five scale, nearly a third of a point less Republican on a seven-point scale, a full point cooler toward Trump on a 0–10 scale and were more pro-immigration. All of these protest-driven changes are statistically significant. This reflects the drop in Trump’s popularity recorded more broadly in American polls in this period. Far from being a disaster for the Left, as in the past, the protests and rioting seem to have invigorated it. America may have stepped over the precipice toward cultural revolution.

In Orwell’s 1984, obliterating the past becomes the first task of the socialist regime: “Every record has been destroyed or falsified, every book rewritten, every picture has been repainted, every statue and street building has been renamed, every date has been altered. And the process is continuing day by day and minute by minute. History has stopped. Nothing exists except an endless present in which the Party is always right.” … The elevation of a principle like anti-racism into a sacred value which cannot be questioned by science means racism becomes impossible to measure, falsify, or bound. Psychologist Nick Haslam’s “concept creep” kicks in, the meaning of “racism,” “hate,” and “harm” expand out of all recognition, and suddenly everything and everyone becomes open to being smeared. Sacred totems like the proletariat or “Black and Indigenous People of Color,” and their demonic “other”—be this “bourgeois” or “white”—have no fixed meaning. As with “racist,” their definitions are fluid and political rather than based in the reality of measurable and statistically-unlikely clusters of values of variables, which is how scientists and ordinary people demarcate terms. George Orwell captured these puritan dynamics nicely, having witnessed factional socialist madness first-hand in Spain, and the bending of truth in Nazi Germany. In 1984, Orwell outlined the process whereby the meaning of words becomes political rather than scientific: “In the end the Party would announce that two and two made five, and you would have to believe it. It was inevitable that they should make that claim sooner or later: the logic of their position demanded it. Not merely the validity of experience, but the very existence of external reality, was tacitly denied by their philosophy. The heresy of heresies was common sense… If both the past and the external world exist only in the mind, and if the mind itself is controllable—what then?”

Eric Kaufman also pointed out that:

The share of white liberals who say racial prejudice is the main reason blacks cannot get ahead has jumped substantially since 2014. This has happened as liberal thought has changed its focus from class to identity issues since the 1960s … [T]he connection between race and racial ideology has weakened considerably: People of color are not the driving force behind most of today’s forms of racial liberalism. The Hidden Tribes study from the More in Common organization — which groups the American electorate on the basis of its views — helps identify the leading proponents of racial liberalism: Of the seven major voting blocs, the most racially liberal are the Progressive Activists, who form just 8 percent of the population. This group is over 80 percent white and only 3 percent African-American. Similarly, a Pew Research Center report finds that the ‘Solid Liberals’ group is overwhelmingly white, and that minority Democrats are more conservative … Yet Trump voters rate minorities relatively warmly. Racial ideology rather than race accounts for their differences with white Democrats: White Republicans reject affirmative action, the notion of white privilege and the idea that racial discrimination continues to hold minorities back. Minorities again rank in between on many of these measures. When it comes to ‘microaggression’ statements such as ‘America is a colorblind society’ or ‘You are so articulate,’ few blacks and Hispanics find these offensive while more liberal whites do.”

And in the presidential election of 2020, while Trump ultimately lost, according to the exit polls, Trump did even better in 2020 with every race and gender except white men.

As Musa al-Gharbi has explained:

Let’s start with gender: across racial and ethnic groups, women shifted towards Trump this cycle [2020]. In the last election, Trump won white women by a margin of 9 percentage points. This year, he won by 11 percentage points. In 2016, Democrats won Hispanic and Latina women by 44 percentage points; in 2020 they won by 39. Last cycle, Democrats won black women by 90 percentage points. This year, by 81 points. That is, in a year when a black woman was on a major party ticket for the first time in US history, the margin between Democrats and Republicans among black women shifted 9 percentage points in the other direction – towards Trump. Trump saw comparable gains with Black and Hispanic men as well. Overall, comparing 2016 and 2020, Trump gained 4 percentage points with African Americans, 3 percentage points with Hispanics and Latinos, and 5 percentage points with Asian Americans. The shifts described in Edison’s exit polls are verified by AP Votecast, which showed similar movement among black and Hispanicvoters this cycle. We can look at The American Election Eve Poll to gain some additional context on this movement. Let’s start with the Hispanic and Latino vote: comparing 2016 and 2020, the margins shifted 47 percentage points towards Trump (or, away from the Democrats) among those of South American ancestry. The margins also shifted 37 percentage points towards the Republican party among those whose families hail from Central America, 35 percentage points among Dominicans, 16 percentage points among Puerto Ricans, 15 percentage points among Mexican Americans and 9 percentage points among Cubans. Indeed, this latter group actually ended up favoring Trump over Biden outright. That is, while recognizing that these populations are not monolithic, and although Democrats won most of the Hispanic and Latino vote overall, nonetheless Hispanic and Latino voters shifted decisively towards Trump this cycle. Similar patterns hold among Asian Americans: Filipino, Korean, Chinese and Indian Americans alike seem to have drifted towards Trump. The trend was so dramatic among Vietnamese Americans that they, like Cubans, actually favored Trump outright. Among Asians, only Japanese Americans seem to have shifted towards the Democrats since 2016. That is, minorities and women (and minority women) – the very people who are supposed to be central to the Democratic coalition, and who have suffered most in the current pandemic and economic recession – seem to have shifted in Trump’s direction across the board. In fact, virtually the only racial or gender constellation the President did not gain with are the people that are often described as his core constituency: white men. In 2016, Trump won white men by a margin of 31 percentage points. In 2020, however, he won this constituency by 23 percentage points. Put another way, comparing 2016 to 2020, white men shifted 8 percentage points in Biden’s direction this year – helping flip the election towards the Democrats, despite Trump’s significant gains among minorities and women across the board.

Charles Blow of the Washington Post also pointed out that “the percentage of L.G.B.T. people voting for Trump doubled from 2016, moving from 14 percent to 28 percent. In Georgia the number was 33 percent.”

As the New York Times reported in April, 2021:

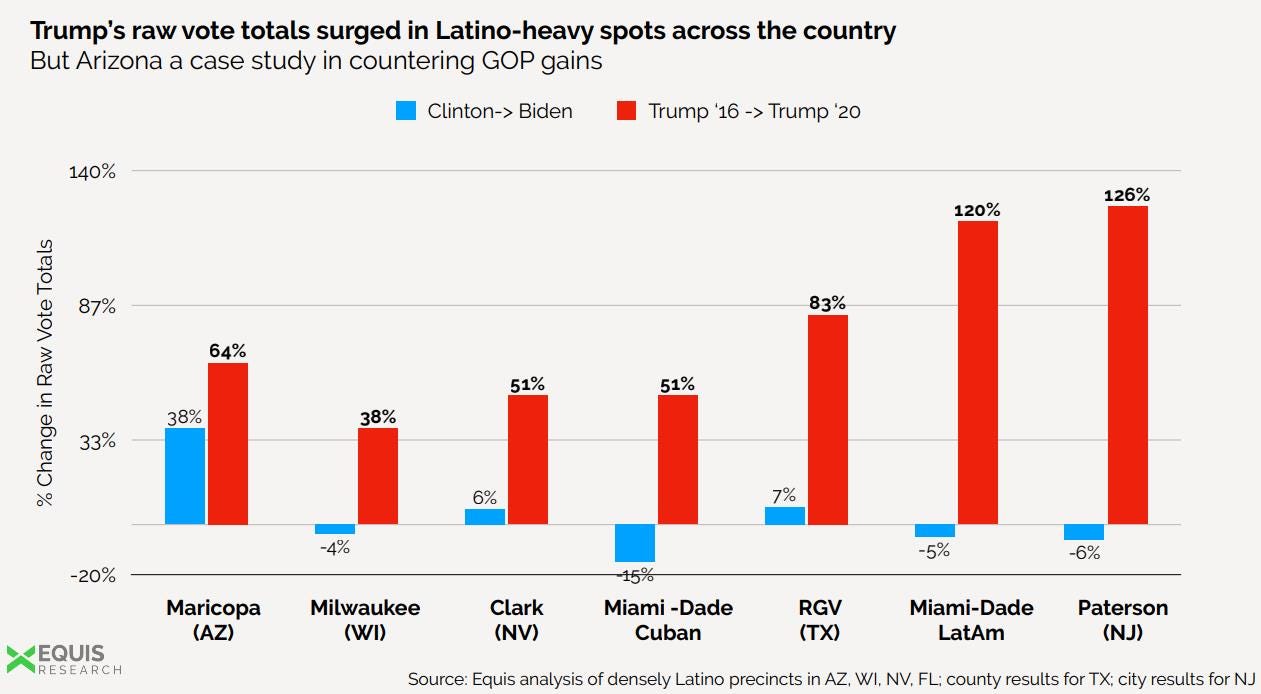

Even as Latino voters played a meaningful role in tipping the Senate and the presidency to the Democrats last year, former President Donald J. Trump succeeded in peeling away significant amounts of Latino support, and not just in conservative-leaning geographic areas, according to a post-mortem analysis of the election that was released on Friday. Conducted by the Democratically aligned research firm Equis Labs, the report found that certain demographics within the Latino electorate had proved increasingly willing to embrace Mr. Trump as the 2020 campaign went on, including conservative Latinas and those with a relatively low level of political engagement. Using data from Equis Labs’ polls in a number of swing states, as well as focus groups, the study found that within those groups, there was a shift toward Mr. Trump across the country, not solely in areas like Miami or the Rio Grande Valley of Texas, where the growth in Mr. Trump’s Latino support has been widely reported.

Michael Barone has described how much better Republicans performed in the 2020 federal elections compared to what pollsters predicted, indicating there are many voters who support Republicans but who are unwilling to risk arousing the mob-like negative reactions that could result were they to publicly express their opinions:

Republican pollster Patrick Ruffini’s chart comparing pre-election polling [“CCES”] and the Associated Press’s VoteCast polling [which is not based on in-person interviews] identifies white college graduates, women as well as men, as voting much more Republican than indicated in pre-election polling.

National Journal’s Josh Kraushaar showed how this produced systemically erroneous results in House races. Both public and partisan polls showed Democrats gaining seats. Instead, Republicans gained 6 to 13. As Kraushaar recounts, Democrats failed to capture the high-education districts they targeted and lost several such districts they had captured in 2018. House polls haven’t been so far off results since at least 1994.

As reported in the Wall Street Journal:

Over the last four years, white liberals have become a larger and larger share of the Democratic Party,” says Democratic polling maven David Shor in an interview with Eric Levitz of New York magazine. The events of 2020 inspired many conservative minorities to vote their values, and current events are yielding another opportunity to advance an agenda of ordered liberty. An Obama campaign veteran, Mr. Shor tells New York that more data on voter history and additional surveys provide a clearer picture of what happened in November than was available at the time. One thing that hasn’t changed, of course, is the need to be wary of the claims of pollsters, but Mr. Shor’s analysis is bound to be interesting to both major parties. Here’s how he sees the 2020 results: “Democrats gained somewhere between half a percent to one percent among non-college whites and roughly 7 percent among white college graduates (which is kind of crazy). Our support among African Americans declined by something like one to 2 percent. And then Hispanic support dropped by 8 to 9 percent. The jury is still out on Asian Americans. We’re waiting on data from California before we say anything. But there’s evidence that there was something like a 5 percent decline in Asian American support for Democrats . . . I don’t think a lot of people expected Donald Trump’s GOP to have a much more diverse support base than Mitt Romney’s did in 2012. But that’s what happened.” “One important thing to know about the decline in Hispanic support for Democrats is that it was pretty broad,” says Mr. Shor.

As reported at the time by Samuel Abrams:

Thanks to data from the new Los Angeles Times/Reality Check Insights poll, we have a better sense of Trump support, and his base was not just in rural, white America. It was also in cities and among non-whites, groups that were widely believed to be locks for the Biden. The views, values, and attitudes of these Americans should not be ignored, or else we risk continuing socio-political fracture and unstable governing coalitions. This new data makes it clear that our nation’s cities nor its small towns and rural regions are not politically monolithic. While just 14 percent of those in living in big cities voted for Trump, that figure climbs for every other spatial conurbation. Roughly a third of residents in small cities along with suburbs of big cities and small cities report voting for Trump, as did 47 percent of residents in rural areas and 46 percent in small towns. Moreover, rural areas were more participatory than big cities, with just 16 percent of rural respondents opting to stay home on Election Day, compared to 27 percent of big city dwellers (and 13 percent of their suburban counterparts). Overall, while cities are categorically more supportive of Biden, in suburbs of small cities, for instance, the numbers of Trump voters are within a handful of points of Biden voters (36 percent to 42 percent). This should not be dismissed as an insignificant. Support for Trump was strong among those who are more formally educated, despite the common rhetoric that they could not possibly support Trump. Americans with high school diplomas split: About a third opted to not vote, a third voted for Biden (33 percent), and another third Trump (35 percent). College graduates look different: only 5 percent sat out the election, 36 percent voted for Trump, and 55 percent chose for Joe Biden. Even here, Biden’s support is not above the 60 percent landslide threshold. The idea that non-Whites support Democrats instead of a racist Republican Party did not work out entirely. For Blacks, 71 percent voted for Biden and only 3 percent for Trump. But only 53 percent of Asian-Americans voted for Biden, with another third checking the box for Trump instead. Whites were split fairly evenly; about 40 percent voted for Trump and Biden respectively. As for those who identify as Hispanic, a quarter still supported and voted for Trump. Just 42 percent of Hispanic identifiers cast ballots for Biden — a plurality, but not an overwhelming majority whatsoever. Aside from Blacks, there was not universal support for Biden among non-Whites. Finally, it is often assumed that younger generations of Americans are overwhelmingly liberal, but that was not apparent in the reported vote data. Silents and Boomers spilt roughly half and half for Trump and Biden and a third of Gen Xers cast ballots for Trump, compared to 46 percent for Biden. Millennials and Gen Zers voted for Biden over Trump a bit more than 2 to 1. Surprisingly, almost a quarter (22 percent) of Millennials voted for Trump, which shows that his support was more widespread and deep than many may have realized. The 2020 exit polls were fraught with measurement issues and thus were hard to trust. With the new data, we now have a better sense of who voted for Trump. His appeal extended well beyond rural, older white America; Younger, suburban, and Hispanic groups supported Trump as well.

Still, those with college degrees generally tend to vote Democrat, as they did in 2020. But as Musa al-Gharbi describes, college degrees are also associated with greater political partisanship and the tendency to perceive things through partisan lenses:

Those who are highly-educated tend to be more politically partisan than most. They are also significantly more likely to conform their evaluations of historical or present circumstances to fit the messaging of party elites. As compared to the general public, cognitively sophisticated voters are much more likely to form their position on issues, or even change their position on issues, based on partisan cues of what they are ‘supposed’ to think in virtue of their identity as Democrats, Republicans, etc. Consequently, people tend to grow more politically polarized as their scientific literacy, numeracy or reflectiveness increases – and evoking scientific studies or statistics in the context of socio-political arguments tends to polarize people even further. By virtue of their tendencies toward political hobbyism, highly-educated people tend to follow political horse-races much more closely than the general public, and are often much better-versed with respect to contemporary political gossip, drama or scandals. Yet they tend to be little more informed than most with regards to more substantive facts – often lacking even rudimentary knowledge about civic institutions and processes. In fact, highly-educated people tend to be less self-aware of their own socio-political preferences than most – typically describing themselves as more left-wing than they actually seem to be. They also tend to be significantly worse at gauging others’ political beliefs, often assuming other people are much more extreme or dogmatic than they actually seem to be. This is perhaps because, compared to the general public, highly-educated or intelligent people tend to be more ideological in their thinking, more ideologically rigid, and more extreme in their ideological leanings. Highly-educated and intelligent people are more likely to grow obsessed with some moral or political cause. They are more likely to overreact to small shocks, challenges or slights. While they are less likely to be prejudiced against others on the basis of things like race, they tend to be far more prejudiced than most against those who seem to think differently than they do, and often look down on those with less education.

As Michael Barone has described, immigrants in the United States trended toward support for President Trump in the 2020 presidential election:

Such behavior was the subject of the New York Times’s graphic team’s report headlined “Immigrant Neighborhoods Shifted Red as the Country Chose Blue.” Readers scrolling down through the story encounter maps of metropolitan Chicago, Miami, Orlando, Houston, San Antonio, Philadelphia, New York, Los Angeles, San Jose, and Phoenix, plus the Rio Grande Valley, with Latino and Asian neighborhoods clearly marked. Red arrows show election precincts’ increases in President Trump’s percentage for 2020 over 2016, with blue arrows sometimes showing increased Democratic margins in areas with mostly affluent white voters. The story highlights the big Trump increases among Miami area Cuban Americans — a trend so large, and so pivotal in giving Trump Florida’s 29 electoral votes, that it was noticed on election night. But what was considered an exception then turns out to have been a particularly vivid example of the rule. Trump still didn’t carry most heavily Hispanic areas. But he got big percentage increases in almost all of them, from Los Angeles and the Rio Grande Valley to Upper Manhattan and the Bronx. And, though this was not noticed at all right after the election, Trump also made gains among Asians — Vietnamese in Orange County, California, Chinese Americans in Silicon Valley and Brooklyn, South Asians and Arabs in Chicago’s northern suburbs.

As the Wall Street Journal reported, candidate Trump in 2020 “suffered his greatest erosion with white voters, particularly white men …” according to the [Tony] Fabrizio analysis. This offset his double digit gains with Hispanics while he performed about as well with blacks as he did in 2016. The former President also … “suffered with white college educated voters across the board.”

As Kevin Kosar summarized the results for Republicans generally following the 2020 federal elections:

[A] closer look reveals many positives for the GOP. They actually gained seats in the House and turned back the much predicted blue wave. In the Senate, they had to defend 21 seats — and lost only three of them. And their president barely lost, despite historically high negative ratings. Had around 81,000 votes gone the other way in a few key states, he would have earned a second term. Biden’s seven-million popular vote margin also looks less impressive if one remembers that three-quarters of that margin came from California. The GOP should also take heart at who voted for them. Professor Andrew Busch of Claremont McKenna College points out “Trump gained four percentage points among blacks (to 12%), four among Latinos (to 32%), and seven among Asians (to 34%).” One exit poll found nearly one in five Black men voted for Trump. In Florida, which so many pollsters had all but given to Joe Biden, Trump triumphed thanks to Latino votes. At the state level, Republicans also did well. They won eight of 11 races for governor and currently occupy 27 of 50 gubernatorial mansions. Republicans also have majorities in 29 of the 50state senates and half the lower chambers. And Republicans achieved all this despite the nation suffering from a pandemic and economic tumults, as well as running with President Trump’s high disapproval ratings.

Richard Alba has pointed out in his book The Great Demographic Illusion that people born of mixed parentage are classified as “minority” when in fact they may not identify with any particular worldview connected to their minority parentage.

And in 2024, these trends continued, with Republicans gaining ground among some minority groups, especially among Hispanics, and from people in rural and suburban areas. Here is a map from the Washington Post showing the shift toward Trump in 2024 in rural and other areas.

Interestingly, the progressive emphasis on the false notion of “systemic racism” in America today was largely rejected by Hispanics. As Ruy Texiera has written:

Take the issue of “structural racism.” In June 2022, the polling firm Echelon Insights released a survey in which respondents were asked to endorse one of two statements: “Racism is built into our society, including into its policies and institutions” or “Racism comes from individuals who hold racist views, not from our society and institutions.” Among participants identified as “strong progressives,” 94% chose the first statement; Hispanics preferred the second statement by a margin of 58% to 36%.

As the Wall Street Journal points out, “Mr. Trump this year won 45% of Hispanics, 38% of Asians, 54% of Hispanic men, and 20% of black men. In 2016 he drew 28% of Hispanics, 27% of Asians, 32% of Hispanic men and 13% of black men. (See the nearby chart.)”

And this graph from the Financial Times shows the shifts in more detail:

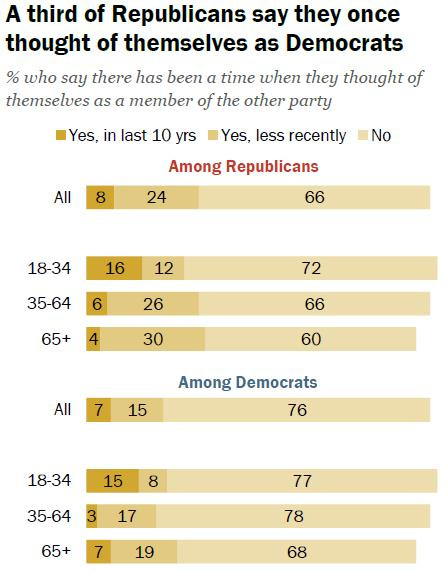

Regarding ideological trends with age generally, as people grow older and have more experience with life, they have a greater tendency to switch party affiliations from Democrat to Republican rather than the other way around.

Republicans are also less likely to have “grown up” in their party.

Researchers have found that in America younger people are more liberal, but gradually become more conservative as they grow older:

The average of this measure (Libcon) generally increases with age both within every 5-year sub-period and among all available cohorts; the shape of these gradients varies considerably across these sub-periods. However, the longer run central tendency is a very well defined concave gradient that rises over the whole life course. The period and cohort versions of this gradient essentially overlap. The change in mean Libcon from early adulthood (25) to old age (80) is substantial (over. 20 on the -1, 1 scale), and around half of this occurs after age 45 … The notion … that millennial youth are much more liberal than their predecessors should be regarded skeptically. And, unless the future is much different than the past, many of these youth will drift right as they age.

We’ll be on vacation until December 2, but in the next essay in this series, we’ll explore how certain mindsets correlate with partisanship.