Mission Statements

“If we could put a man on the moon …”

I was reading Daniel Coupland’s useful little book for teachers called Tried & True: A Primer on Sound Pedagogy, the first chapter of which is titled “Follow the School’s Mission.” Coupland writes:

If the mission [of the school] is not clearly labeled, you should be able to recognize it by its language. Mission statements [of schools] will include words related to knowing things (e.g., knowledge, understanding, and wisdom). They will often refer to the skills that students will acquire (e.g., “learning how to learn” or “a lifetime of learning”) … Ask yourself what the words mean and look up their formal definitions.

I was curious as to what our local public high school’s mission statement said, so I looked it up and found this (note that the term “Titans” refers here to students):

The first thing I noticed was that this mission statement did not contain any of the concepts mentioned by Coupland -- knowledge, understanding, and wisdom -- that are central to most other schools’ mission statements. Those concepts are also central to what we know about the science of learning, a topic ably explored by Daniel Willingham in his book Why Don't Students Like School?: A Cognitive Scientist Answers Questions About How the Mind Works and What It Means for the Classroom.

Willingham writes about the primary role background knowledge plays in the ability of students to remember things so they can learn even more:

This final effect of background knowledge – that having factual knowledge in long-term memory makes it easier to acquire still more factual knowledge – is worth contemplating for a moment. It means that the amount of information you retain depends on what you already have. So, if you have more than I do, you retain more than I do, which means you gain more than me. To make the idea concrete (but the numbers manageable), suppose you have ten thousand facts in your memory but I have only nine thousand. Let's say we each remember a percentage of new stuff, and that percentage is based on what's already in our memories. You remember 10% of the new facts you hear, but because I have less knowledge in long-term memory, I remember only 9% of new facts. Table 2.1 shows how many facts each of us has in long-term memory over the course of 10 months, assuming we're each exposed to five hundred new facts each month. By the end of 10 months, the gap between us has widened from 1000 facts to 1043 facts. Because people who have more in long-term memory learn more easily, the gap is only going to get wider. The only way I could catch up is to make sure I am exposed to more facts than you are. In a school context, I have some catching up to do, but it's very difficult because you are pulling away from me at an ever-increasing speed.

I have of course made up all of the numbers in the foregoing example, but we know that the basics are correct – the rich get richer.

Willingham adds that:

Knowledge is [even] more important, because it's a prerequisite for imagination, or at least for the sort of imagination that leads to problem solving, decision making, and creativity … [T]he cognitive processes that are most esteemed – logical thinking, problem solving, and the like – are intertwined with knowledge. It is certainly true that facts without the skills to use them are of little value. It is equally true that one cannot deploy thinking skills effectively without factual knowledge … [T]hinking well relies on knowledge. Knowledge allows you to bridge the gaps writers leave in prose and guides your interpretation when sentences are ambiguous. Knowledge is essential for chunking, the process that saves room in working memory, and so facilitates reasoning. Sometimes knowledge substitutes for reasoning, when you simply recall a previous problem solution, and other times, knowledge is required to deploy a thinking skill, as when a scientist judges that an experimental result is anomalous. Rather than thinking of knowledge as data that might be plugged into thinking processes, it's better to think of knowledge and thinking as intertwined … If factual knowledge makes cognitive processes work better, the obvious implication is that we must help children learn background knowledge.

Our local high school’s mission statement also fails to refer to concepts like perseverance or grit, skills schools have to teach if students are going to have much hope of thriving in the real world. Yet our local school board proposed prohibiting teachers from giving students a zero grade for work not turned in. That potential dumpster fire was ultimately squelched by a blanket of common sense was thrown over it. That common sense is also backed by science, which shows that actually doing the work is directly associated with success. As Willingham writes:

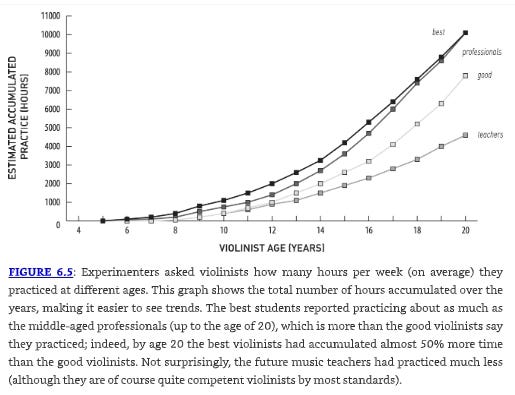

A number of researchers have tried to understand expertise by examining the lives of experts and comparing them to what we might call near-experts. For example, one group of researchers asked violin players to estimate the number of hours they had practiced the violin at different ages. Some of the subjects (professionals) were already associated with internationally known symphony orchestras. The others were music students in their early twenties. Some of the students (the best violinists) had been nominated by their professors as having the potential for careers as international soloists; others (the “good” violinists) were studying with the same goal, but their professors thought they had less potential. Subjects in the fourth group were studying to be music teachers, not professional performers. Figure 6.5 shows the average cumulative number of hours that each of the four groups of violinists practiced between the ages of 5 and 20. Even though the good violinists and the best violinists were all studying at the same music academy, there was a significant difference in the amount of practice since childhood reported by the two groups. Other research shows the importance of practice to a wide range of skills, from sports to games like chess and Scrabble.

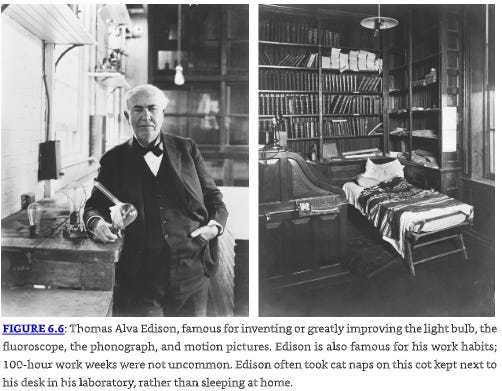

Other studies have taken a more detailed biographical approach. Over the last 50 years there have been a few instances in which a researcher has gained access to a good number (10 or more) of prominent scientists, who have agreed to be interviewed at length, take personality and intelligence tests, and so forth. The researcher has then looked for similarities in the backgrounds, interests, and abilities of these great men and women of science. The results of these studies are fairly consistent in one surprising finding. The great minds of science were not distinguished as being exceptionally brilliant, as measured by standard IQ tests; they were very smart, to be sure, but not the standouts that their stature in their fields might suggest. What was singular was their capacity for sustained work. Great scientists are almost always workaholics. Each of us knows his or her limit; at some point we need to stop working and watch a stupid television program, hop on Facebook, or something similar. Great scientists have incredible persistence, and their threshold for mental exhaustion is very high.

Angela Duckworth examined this quality not just in scientists, but in musicians, West Point cadets, spelling bee competitors, and others. Just as the most successful scientists are not necessarily those with the highest IQ, so too researchers had a hard time identifying characteristics of very successful people in other fields, other than “they've put more work into it than others.” Duckworth identified two essential personality components – persistence and passion for a long-term goal – and called the combination “grit.”

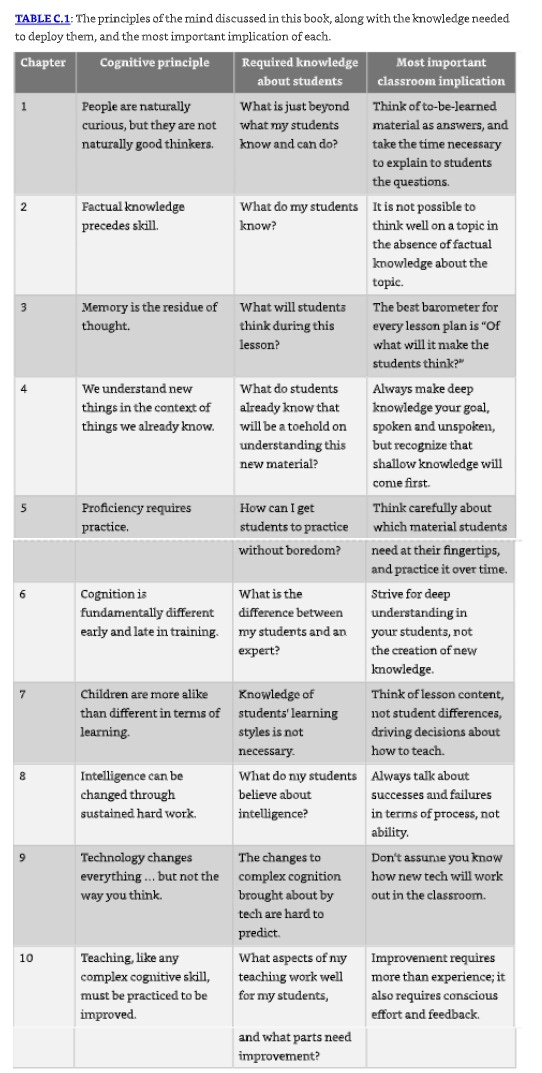

Reprinted here is Willingham’s useful chart summarizing these and several other fundamental conclusions of the science of learning:

If our local high school’s mission statement were to incorporate the science of learning, it would read something like: “Our mission is to foster academic excellence by instilling students with the background knowledge necessary for continued learning, encouraging critical thinking through use of the Socratic method, and developing the personal responsibility and the grit necessary to see projects through.”

Instead, our local high school’s mission statement contains none of these concepts that are the heart of what we know about the science of learning. Besides having a misplaced comma after “civically engaged,” the school’s mission statement contains lots of politically activist buzzwords like equity, anti-racism, and “restorative framework,” the false premises of which have been explored in some detail in previous essays. But at root, proponents of “anti-racism,” as popularized by the now largely discredited author Ibram X Kendi, make the false assumption that, as Kendi says “When I see racial disparities, I see racism.” Of course, there are many explanations for disparities among people grouped by race that have nothing to do with racism. As Robert Pondiscio writes:

A recent report from the University of Virginia—Good Fathers, Flourishing Kids—confirms what many of us know instinctively but rarely see, or avoid altogether, in education debates: The presence and engagement of a child’s father has a powerful effect on their academic and emotional well-being. It’s the kind of data that should stop us in our tracks—and redirect our attention away from educational fads and toward the foundational structures that shape student success long before a child ever sets foot in a classroom. The research … co-authored by a diverse team … finds that children in Virginia with actively involved fathers are more likely to earn good grades, less likely to have behavior problems in school, and dramatically less likely to suffer from depression. Specifically, children with disengaged fathers are 68% less likely to get mostly good grades and nearly four times more likely to be diagnosed with depression. These are not trivial effects. They are seismic. Most striking is the report’s finding that there is no meaningful difference in school grades among demographically diverse children raised in intact families. Black and white students living with their fathers get mostly A’s at roughly equal rates—more than 85%—and are equally unlikely to experience school behavior problems. The achievement gap, in other words, appears to be less about race and more about the structure and stability of the family.

Now, I doubt any teachers at the school had much if anything to do with the wording of the school’s mission statement. Rather, it reads like it was written by school administrators steeped in the far-left ideologies common in education schools, as if to say “Our mission is to allow detached administrators to express their self-importance though virtue-signaling aimed at the political tribe that secures their funding.”

Ultimately, I doubt this particular mission statement drives anything other than the virtue-signaling egos of the school’s administrators. In my experience, the large majority of teachers simply want to teach, and follow the best practices that will allow their students to learn. As a result, our local high school’s mission statement says much more about the bureaucrats who hover over the school than it does about those inside them. (Indeed, our local system’s administrators occupy a wholly separate building unconnected to any building where teaching occurs. Teachers derisively refer to the building as “Central.”)

But if a school is going to have a mission statement at all, it should at least follow the basic principles set down by Peter Drucker, who first popularized the mission statement in his book The Practice of Management, in 1954, in which he states that defining an organization's purpose is a central task of management because it sets the direction, coherence, and justification for everything the organization does, creating a shared sense of purpose to motivate employees, help them understand their role, and foster unity across departments. But instead of setting a direction, our local high school’s mission statement triggers an eye roll.

That mission statement seems so far afield from the realm of education that it brings to mind the metaphor of the “self-licking ice cream cone,” which refers to a situation in which an organization loses sight of its proper mission to serve others and becomes single-mindedly focused on perpetuating the norms of its own bureaucracy. S. Pete Worden, former Deputy of Technology at the Defense Department, was one of the first to popularize the phrase back in 1992.

Worden understood that, over time, organizations move away from their original missions and come to exist solely to preserve themselves, such that the organization operates in ways it imagines will ensure next year’s budgets and bonuses.

Like the NASA programs that lost sight of their mission to create innovative designs in favor of designing their programs to maximize their funding, our local public school system has a habit of falling for administrator-driven programs without asking tough questions. One example is the craze of “social and emotional learning” routines that teachers and students find useless and ineffective. Another is the “restorative practices” program, which relaxes school discipline in favor of coddling disruptive students by inviting them to “talk through” their issues instead of removing them from the classroom so all the other students can learn.

Imagine you’re a teacher faced with a disruptive student who defies repeated attempts to get them to correct their behavior so all the other students can learn. Instead of sending the student to the principal’s office, under the “restorative practices” program imposed by administrators you’d have to somehow work through the steps in this flowchart (it’s sadly real):

It makes one wonder, “If we could put a man on the moon, why can’t we solve the problem of removing disruptive students from the classroom?”

And speaking of putting a man on the moon, it’s worth reminding ourselves how well our nation performed in accomplishing that mission, which was set out in statutory text in Section 102(c) of the National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958:

The aeronautical and space activities of the United States shall be conducted so as to contribute materially to one or more of the following objectives: (1) The expansion of human knowledge of phenomena in the atmosphere and space; (2) The improvement of the usefulness, performance, speed, safety, and efficiency of aeronautical and space vehicles; (3) The development and operation of vehicles capable of carrying instruments, equipment, supplies, and living organisms through space; (4) The establishment of long-range studies of the potential benefits to be gained from, the opportunities for, and the problems involved in the utilization of aeronautical and space activities for peaceful and scientific purposes; (5) The preservation of the role of the United States as a leader in aeronautical and space science and technology and in the application thereof to the conduct of peaceful activities within and outside the atmosphere; (6) The making available to agencies directly concerned with national defense of discoveries that have military value or significance, and the furnishing by such agencies, to the civilian agency established to direct and control nonmilitary aeronautical and space activities, of information as to discoveries which have value or significance to that agency; (7) Cooperation by the United States with other nations and groups of nations in work done pursuant to this Act and in the peaceful application of the results thereof; (8) The most effective utilization of the scientific and engineering resources of the United States, with close cooperation among all interested agencies of the United States in order to avoid unnecessary duplication of effort, facilities, and equipment.

This plain and direct statement of intent led to following, as described by Charles Fishman in his excellent book One Giant Leap: The Impossible Mission That Flew Us to the Moon:

[W]hen President John Kennedy declared in 1961 that the United States would go to the Moon, he was committing the nation to do something we couldn’t do. We didn’t have the tools, the equipment—we didn’t have the rockets or the launchpads, the spacesuits or the computers or the zero-gravity food—to go to the Moon. And it isn’t just that we didn’t have what we would need; we didn’t even know what we would need. We didn’t have a list; no one in the world had a list. Indeed, our unpreparedness for the task goes a level deeper: we didn’t even know how to fly to the Moon. We didn’t know what course to fly to get there from here. And, as the small example of lunar dirt shows, we didn’t know what we would find when we got there. Physicians worried that people wouldn’t be able to think in zero gravity. Mathematicians worried that we wouldn’t be able to work out the math to rendezvous two spacecraft in orbit—to bring them together in space, docking them in flight both perfectly and safely. And that serious planetary scientist from Cornell worried that the lunar module would land on the Moon and sink up to its landing struts in powdery lunar dirt, trapping the space travelers. Every one of those challenges was tackled and mastered between May 1961 and July 1969. The astronauts, the nation, flew to the Moon because hundreds of thousands of scientists and engineers, managers and factory workers unraveled a series of puzzles, a series of mysteries, often without knowing whether the puzzle had a good solution. In retrospect, the results are both bold and bemusing. The Apollo spacecraft ended up with what was, for its time, the smallest, fastest, and most nimble and most reliable computer in a single package anywhere in the world. That computer navigated through space and helped the astronauts operate the ship. But the astronauts also traveled to the Moon with paper star charts so they could use a sextant to take star sightings—like the explorers of the 1700s from the deck of a ship—and cross-check their computer’s navigation. The guts of the computer were stitched together by women using wire instead of thread. In fact, an arresting amount of work across Apollo was done by hand: the heat shield was applied to the spaceship by hand with a fancy caulking gun; the parachutes were sewn by hand, and also folded by hand. The only three staff members in the country who were trained and licensed to fold and pack the Apollo parachutes were considered so indispensable that NASA officials forbade them to ever ride in the same car, to avoid their all being injured in a single accident … Apollo also accomplished [the] mission which John F. Kennedy first set for it: it powered America into the leading role in space. It took most of the decade, in fact, but it turned out that democratic capitalism could not be overmatched, even in space … it was not, in fact, simply two nations racing for the Moon. The Soviets had made it “a test of the system,” as Kennedy put it. Which system had the resources and the skill and the grit to get to the Moon— communism or democracy? The landing of the Eagle on the Moon, the moments when Armstrong and Aldrin stepped off the ladder onto the gray lunar ground— those represented a soaring accomplishment of human ingenuity. The moment when they unfurled the American flag, for all the complexity of America’s role in the world, that underscored that it was also an achievement of human freedom. The American flag meant something very different from the Soviet flag. Instead of the triumph of tyranny, it was just the opposite: going to the Moon is forever the symbol of what freedom can accomplish, of how far human aspiration can take you.

The following is a great illustration of the “all hands on deck” vibe of the time:

For the first Moon walk ever, Sonny Reihm was inside NASA’s Mission Control building, watching every move on the big screen. Reihm was a supervisor for the most important Moon technology after the lunar module itself: the spacesuits, the helmets, the Moon walk boots. And as Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin got comfortable bouncing around on the Moon and got to work, Reihm got more and more uncomfortable. The spacesuits themselves were fine. They were the work of Playtex, the folks who brought America the “Cross Your Heart Bra” in the mid-1960s. Playtex had sold the skill of its industrial division to NASA in part with the cheeky observation that the company had a lot of expertise developing clothing that had to be flexible and also form-fitting … Reihm should have been having the most glorious moment of his career. He had joined the industrial division of Playtex, ILC Dover, in 1960 at age twenty-two, and by the time of the Moon landing, before he turned thirty, he had become the Apollo project manager. His team’s blazing white suits were taking men on their first walk on another world. They were a triumph of technology and imagination, not to mention politics and persistence. The spacesuits were completely self-contained spacecraft, with room for just one. They had been tested and tweaked and custom-tailored. But what happened on Earth really didn’t matter, did it—that’s what Reihm was thinking. There was only one test that mattered, and Aldrin was conducting it right there, right now, in full view of the whole world, on the airless Moon, with unabashed enthusiasm. If Aldrin should trip and land hard on a Moon rock, well, a tear in the suit wouldn’t be a seamstress’s problem. It would be a disaster. The suit would deflate instantly, catastrophically, and the astronaut would die, on TV, in front of the world. That’s what Reihm was thinking about … Reihm knew, of course, that the astronauts were just out there “euphorically enjoying what they were doing.” If the world was excited about the Moon landing, imagine being the two guys who got to do it. In fact, according to the flight plan, right after the landing, Armstrong and Aldrin were scheduled for a five-hour nap. They told Mission Control they wanted to ditch the nap, suit up, and get outside. They hadn’t flown all the way to the Moon in order to sleep. And there really wasn’t anything to worry about. There was nothing delicate about the spacesuits. Just the opposite. They were marvels: 21 layers of nested fabric, strong enough to stop a micrometeorite, but still flexible enough for Aldrin’s kangaroo hops and quick cuts. Aldrin and Armstrong moved across the Moon with enviable light-footedness … Reihm’s anxiety, in fact, is a kind of time machine. We know how the story ended: every Moon mission was a success. Even Apollo 13, which was a catastrophe, was a triumph. Every spacesuit worked perfectly. Astronauts did trip and fall—they skipped, bunny-hopped, skidded to their knees, did pushups to stand upright, jumped too high, and fell over backward. As crews got more experience and more confidence, they would trot at high speed across the Moon’s surface—carefree—in that distinctive one-sixth-gravity locomotion. Once we got to the Moon, nothing much went wrong, not with the spacesuits or anything else.

The fantastic accomplishments of the moon mission occurred so long ago, but the phrase “If we can put a man on the Moon … ” still resonates. As Fishman writes:

We still use the phrase in 2018 for the same reason we did in 1968: going to the Moon remains one of the most amazing things ever accomplished … Seventy percent of Americans today weren’t born, or were younger than five, when we first went to the Moon—which is to say, for 70 percent of Americans, the Moon landings are something to find on YouTube or in books. By the end of 2018, eight of the twelve men who walked on the Moon had died. Most of those who led the effort have died, as have most of the hundreds of thousands of Americans who worked to make it possible. But the appeal of the accomplishment—which 50 years later is often separated from both the politics that inspired it and what it cost—retains powerful allure.

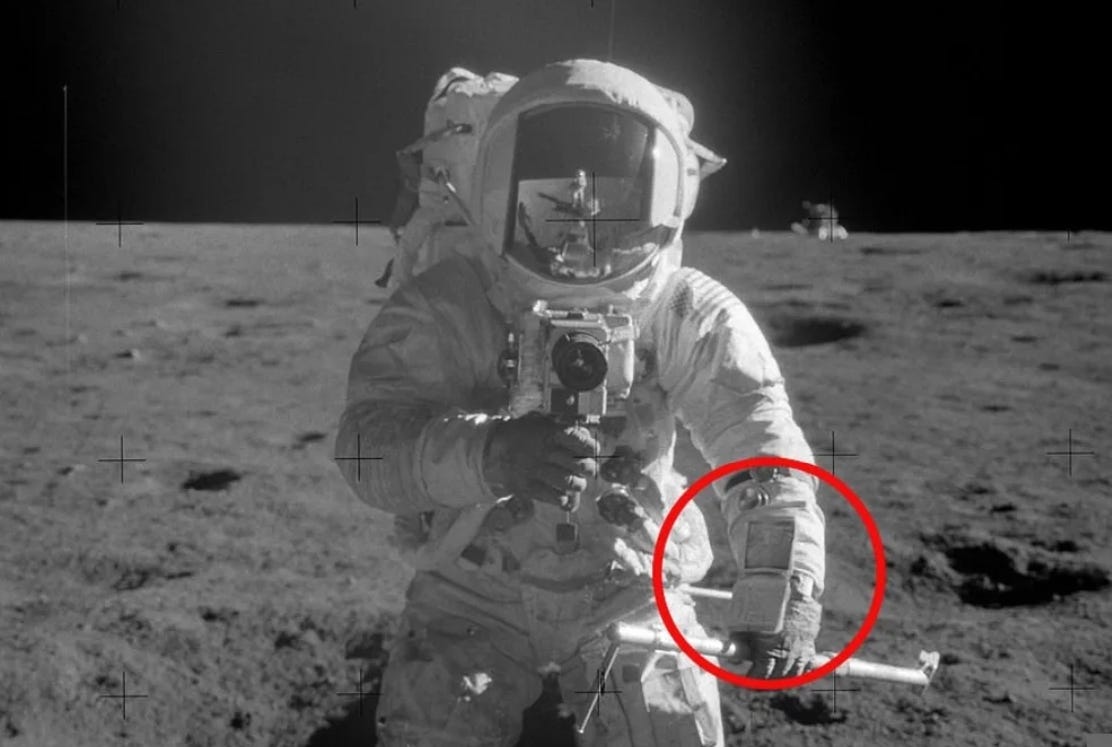

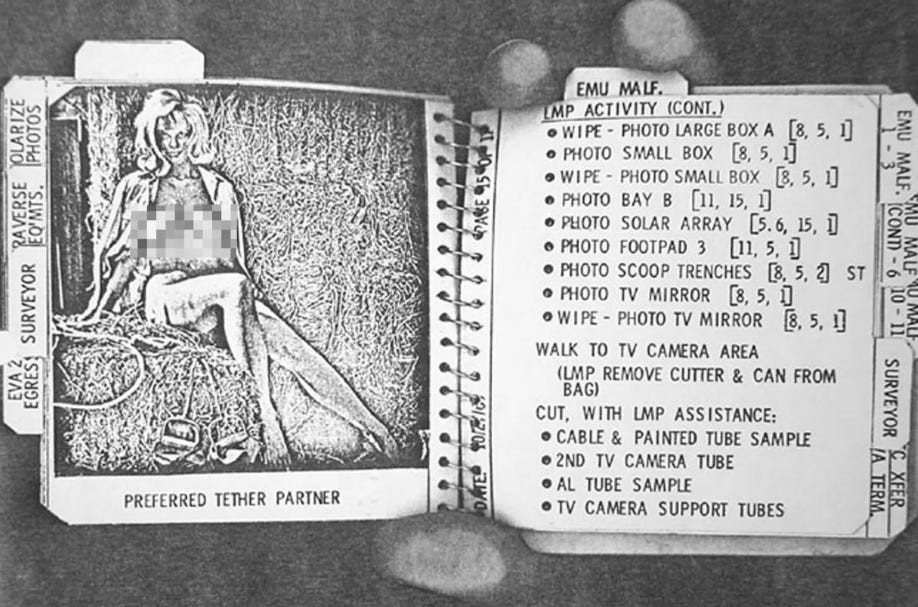

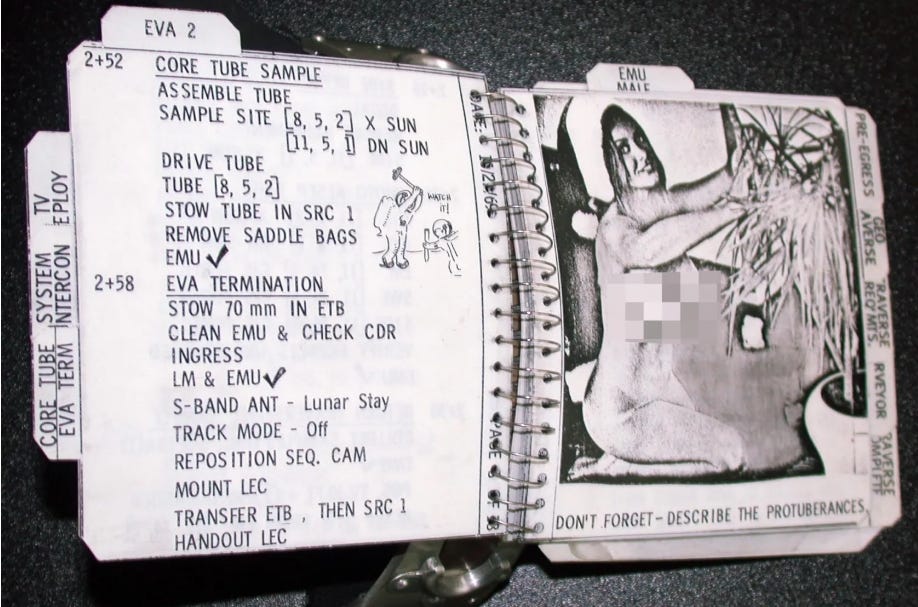

And on the Apollo 12 mission they had fun doing it, too, even if the fun was politically incorrect:

The [moon mission] checklists were typical NASA technical documents: cryptic acronyms, brief instructions, the occasional diagram. But on about half the pages someone has sketched lighthearted cartoons of astronauts going about their tasks on the Moon— setting up a radio antenna, using a hammer to pound the flagpole into the lunar surface, photographing each other. For Conrad and Bean, the cuff checklists contained a cheekier surprise. Each one has pictures of two Playboy playmates, the photos taken directly from the magazine, photocopied down in size, put on the special paper, laminated, and secretly bound into the checklists after they had been reviewed by the astronauts. Bean was apparently the first to find one of the playmates in his checklist; she’s about nine pages in, smiling and wearing a Santa hat and nothing else, the caption supplied by Bean’s NASA colleagues: “Don’t forget— describe the protuberances.” “It was about two and a half hours into the extravehicular activity,” said Bean. “I flipped the page over and there she was. I hopped over to where Pete was and showed him mine, and he showed me his.” There’s not a whisper of the discovery on the radio exchanges between Apollo 12 and Mission Control. “We didn’t say anything on the air,” Bean said. “We thought some people back on Earth might become upset if they found out we had Playboy playmates in our checklists. They would have said, ‘This is where our tax money is going?’ ” But the astronauts appreciated the prank. “We giggled and laughed so much,” said Conrad, “that people accused us of being drunk or having ‘space rapture.’” Word about the Playboy playmates reaching the Moon apparently never reached reporters, during Apollo 12’ s flight or after. The first story about it appeared in Playboy itself, in December 1994, on the 25th anniversary of the flight. But there is inadvertent photographic evidence of the prank right from the surface of the Moon. One of the classic photos from Apollo 12 is a close-up portrait of Commander Pete Conrad, in his spacesuit, facing the camera and holding another camera. The lunar module is visible in the distance over his left shoulder. Alan Bean, taking the picture, is reflected in the visor of Conrad’s spacesuit helmet. And on Conrad’s left arm his cuff checklist is open, and it just happens to be open to the page where a playmate is reclining on a hay bale (caption: “preferred tether partner”). In the photo, the image is too grainy to make out if you don’t know it’s there, but if you zoom in on the photo, you can just make her out. Conrad had that photo framed in his home but didn’t notice for years that on his wrist was Reagan Wilson, October 1967 Playmate of the Month. A Playboy playmate not only flew to the Moon; she was photographed there.

Government bureaucracy didn’t stop pictures of Playmates from going to the moon, but even President John F. Kennedy had feared bureaucracies and labor unions would gum up the moon missions. As Fishman writes:

Kennedy worried that bureaucracy or labor issues would somehow hobble an effort that wasn’t even under way yet. Without realizing it, he imagined the culture that NASA would go on to create, a culture that owed much to Kennedy’s call itself—something those who worked on Apollo also mention. Kennedy said in that first speech, “Every scientist, every engineer, every serviceman, every technician, contractor and civil servant [must] give his personal pledge that this nation will move forward, with the full speed of freedom in the exciting adventure of space.”

And just like tribal progressive politics can hamstring sound educational policy, it threatened to derail the moon missions – but NASA, at the time, resisted. Many people don’t remember, but large-scale political protests went alongside the moon missions. As Fishman recounts:

The day before the launch of Apollo 11, NASA administrator Thomas Paine met with the protesters at Cape Kennedy who were led by the Reverend Ralph Abernathy. As Paine recounted the meeting, Abernathy told him that one-fifth of Americans lacked adequate food, shelter, clothing, and medical care. “The money for the space program, [Abernathy] stated, should be spent to feed the hungry, clothe the naked, tend the sick, and house the shelterless.” Paine told the protesters, “If we could solve the problems of poverty in the United States by not pushing the button to launch men to the Moon tomorrow then we would not push that button.” It was a common critique in the 1960s, and it still is today: that somehow, by devoting time, money, and energy to space travel, we must of necessity neglect other things. If we go to space, we can’t have good schools or accessible health care or clean water or a strong spirit of community. It’s like saying art museums cause poverty.

Of course, there are always opportunity costs in the sense that every dollar spent on one thing can’t be spent on another. But innovation-based missions are usually more worthy of government funding than overly-generous programs that perpetuate dependence. One of the most memorable speeches describing the original moon missions’ collective instilling of “grit” among Americans is President John F. Kennedy’s speech of November 21, 1963, in which he said:

Frank O’Connor, the Irish writer, tells in one of his books how, as a boy, he and his friends would make their way across the countryside, and when they came to an orchard wall that seemed too high and too doubtful to try, and too difficult to permit their voyage to continue, they took off their hats and tossed them over the wall— and then they had no choice but to follow them. This nation has tossed its cap over the wall of space, and we have no choice but to follow it.

Fishman describes how a NASA administrator explained the importance of the moon mission to the leader of the protesters:

In that meeting between the anti- poverty protesters, led by Reverend Abernathy, and NASA administrator Paine the day before the launch of Apollo 11, Paine went on to tell Abernathy and the group that “the great technological advances of NASA were child’s play compared to the tremendously difficult human problems with which he and his people were concerned. I said that [Abernathy] should regard the space program, however, as an encouraging demonstration of what the American people could accomplish when they had vision, leadership and adequate resources of competent people and money to overcome obstacles. I said I hoped that he would hitch his wagons to our rocket, using the space program as a spur to the nation to tackle problems boldly in other areas.” Paine’s detailed recollection comes from a memo he wrote for his files two days later, as Apollo 11 raced for the Moon, a memo tracked down by the historian Roger Launius. At the end of the meeting that afternoon, Paine asked Abernathy and his fellow protesters to include the Apollo 11 astronauts in their prayers when they held a prayer service later in the day. Abernathy, wrote Paine, “responded with emotion that they would certainly pray for the safety and success of the astronauts, and that as Americans they were as proud of our space achievements as anybody in the country.”

As Fishman writes:

The problems of inadequate schools, of poverty, of hunger, of health care, aren’t susceptible to a “Moon race” fix because they are part of the whole social, cultural, and economic system in which we live. Even students attending the very same school have very different experiences, because they are different children with different teachers … [T]he leap to the Moon is not the perfect model for solving the problems of poverty or any of the other problems of American society on Earth. But it does contain a wider truth: with inspired leadership, with resources, and, most important, with clarity of purpose, with an explanation of the need, Americans will solve the hardest problems they are asked to tackle. But we have to be asked … The hard part is the human part: motivation, giving people a role and a goal.

Fishman is optimistic for America going forward:

What has become of the America that planted a flag on the Moon? We used to do things like that. Why don’t we anymore? That spirit of America is just fine. It’s alive and well. In the halo after Apollo, it created Microsoft and Intel, Apple and Google. Have you noticed that all of human knowledge is accessible from a device that fits in your hand? Did not creating that world—the world we have so quickly come to take for granted—require spirit and determination, vision and daring? Of course it did. It didn’t always require physical courage, but it required intellectual courage and relentless determination and boldness of imagination. Americans created the internet. Americans decoded the genome. American spaceships leap the solar system to unlock the mysteries of Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and all kinds of quirky asteroids and comets and moons.

The mission statements of the companies Fishman mentions focus directly on the proper goals of their respective organizations:

Microsoft: “Microsoft’s mission is to empower every person and every organization on the planet to achieve more.”

Intel: “We create world-changing technology that improves the life of every person on the planet … Our customers’ success is our obsession. We promise to deliver the technology leadership and reliable, top-quality products they need and expect.”

Apple (under Steve Jobs): “To make a contribution to the world by making tools for the mind that advance humankind.”

Google: “Our mission is to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.”

Those mission statements — which directly address the purpose of their enterprises — are a far cry from the off-point platitudes of the mission statement of our local high school.

Which got me thinking more broadly, “What’s a good mission statement for living life?” A good place to start is with the Golden Rule, an interesting history of which by Jeffrey Wattles will be the subject of my next essay.

Paul, Great piece. Learned a lot, as always. Merry Christmas!