Mismeasuring Economic Inequality – Part 14

The benefits cliff as a disincentive to earn more income.

The way most government benefits program work, once you make a certain amount of money, you’re disqualified from various government benefits programs. This is inevitable if one wants to limit government benefits to those below a certain income. But just as inevitably, people will reach a point at which making more than a certain amount of income will actually decrease their disposable income because there are now so many government benefits provided.

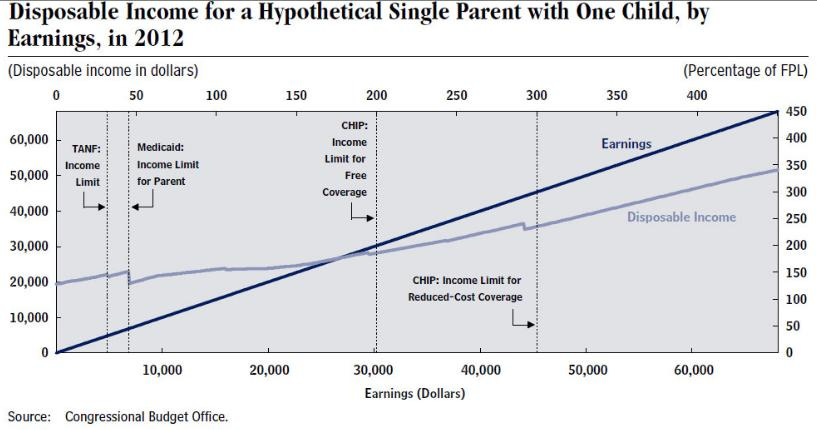

As the following two charts show, because government benefit payments generally stop once certain income thresholds are reached, one’s disposable income actually decreases once one makes more than a certain amount of money.

This creates a financial incentive for people to avoid making “too much money” so they can stay on government benefits programs. The chart below (from the Congressional Budget Office) shows much the same as the previous chart (that is, if earnings rise past a certain point, disposable income falls).

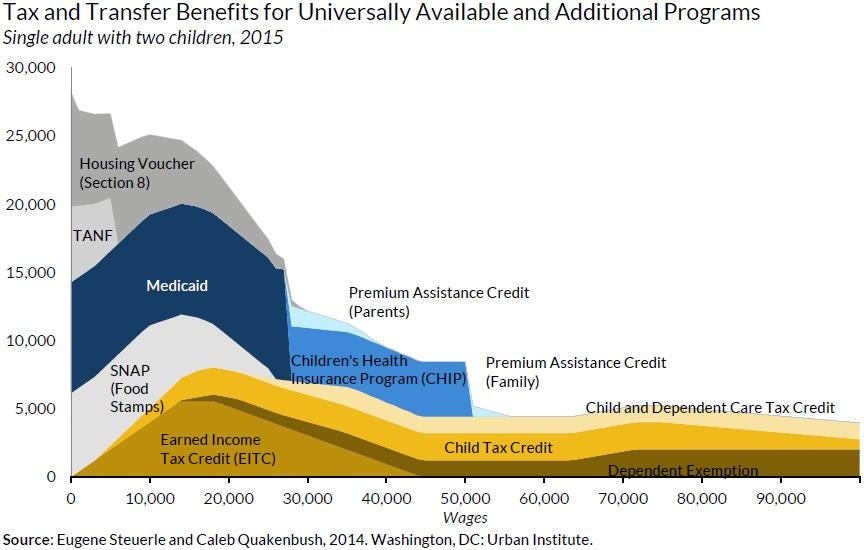

The following chart breaks down the components of the “benefit cliff” more clearly (showing which benefits one loses as one makes more income).

Researchers have found that the Earned Income Tax Credit helps reduce negative effects of the marginal tax rates lower-income people face when removing themselves from welfare. Those researchers found the following:

We find that the EITC helps “pay for itself” through increases in tax revenue and decreases in government transfers in the following year. Average-treatment-effect estimates show that the EITC has a self-financing rate of 83 percent, so that each $1 of EITC spending has a net budgetary cost to government of $0.17.59 Instead of costing $73 billion, the 2017 EITC’s net cost was about $12 billion, costing taxpayers less than the school lunch and breakfast programs. If anything, the EITC’s net cost appears to be zero or even negative when longer-run and spillover effects are accounted for.61 We find that recent EITC expansions also continue to largely pay for themselves. Additional EITC expansions today—for adults with or without children—would likely continue to increase labor supply, decrease poverty, and improve the well-being of lower-income families at a cost much lower than the budgetary cost … Lower-income households deciding whether to join the labor force face high marginal and average tax rates, often over 50 percent and occasionally over 100 percent, when government transfers is accounted for. The EITC acts as a tax cut on these lower-income households, decreasing these high tax rates by up to 45 percentage points.

However, the combined effect of this dynamic nationwide leads to the following results. “One in four low-wage workers,” according to a study, “face lifetime marginal net tax rates above 70 percent, effectively locking them into poverty … The U.S. has a plethora of federal and state tax and benefit programs, each with its own work incentives and disincentives … [These polices were] adopted with apparently no regard to their collective impact.” Social Security, for example, “has 2,728 primary rules governing the receipt of its 12 benefits, plus tens of thousands of secondary rules.” A person who earns an extra dollar, they continue, might lose 22 cents from the earned-income tax credit, or forfeit thousands in Medicaid benefits, or face almost $800 in higher Medicare premiums, “and the list goes on.” The authors calculate that, with levies and transfers considered, the overall median one-year marginal net tax rate is 37.6%. The rate covering earnings over the estimated remaining lifetime is higher, 43.2%. This reflects the later double taxation of savings, such as after a capital gain. Also, making money one year can mean losing future aid from programs with asset limitations, including food stamps and Supplemental Security Income. For the richest 5%, the authors say the one-year median marginal net tax rate is 43.7%, while the lifetime median is 53%. It’s worse for many people at the bottom, where a quarter of the time the lifetime marginal net tax rate exceeds 70%. By earning an extra $1,000, “one in four of our poorest households, regardless of age, make between two and three times as much for the government than they make for themselves.” The study offers some extreme cases: an Oregonian mother of three who earns $37,000. Another $1,000 could make her ineligible to get Section 8 housing assistance, with a lifetime present value of $184,000. And after earning an additional $1,000, a New York couple with four children might forfeit $2,200 in cash benefits and food aid. But years down the road that lets them slide under Medicaid’s asset threshold, with lifetime benefits of $20,000.

As Angela Rachidi writes:

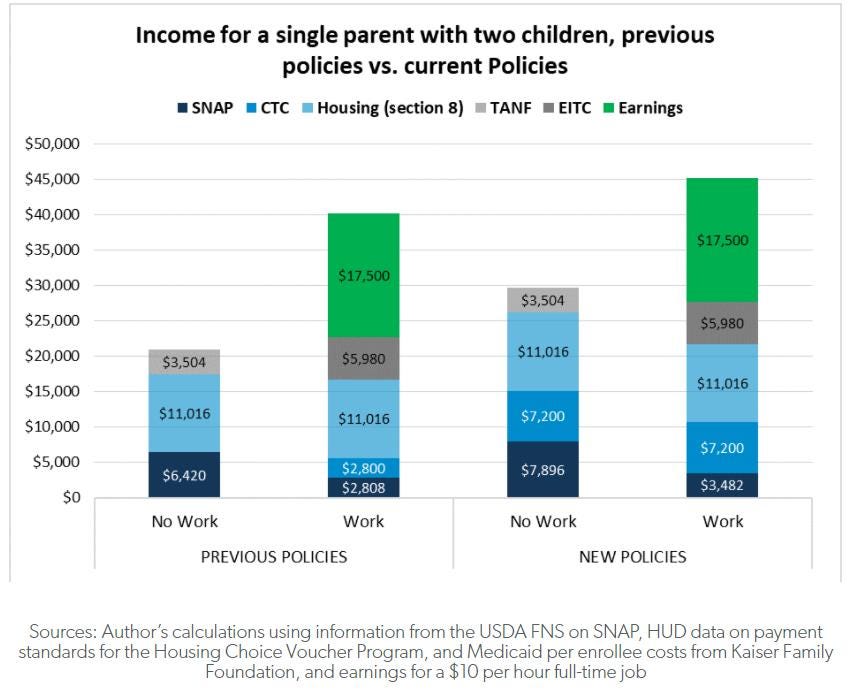

Work disincentives have been a long-standing problem in US safety net programs. However, current efforts by President Biden and the Democrats will only make matters worse. Under previous policies (before changes to SNAP and the CTC), a single mother with two children in Oklahoma City could increase her income by nearly $20,000 per year by working full-time at $10 per hour, which would be more than her earnings alone ($17,500) because of the EITC and CTC. If the Democrats fully implement their new policies, the same mother stands to gain only $15,562, less than her earnings because she loses SNAP benefits as her income increases. The new policies raise the effective marginal tax rate on earnings for low-income families and make employment less attractive, something AEI economists Alex Brill and Kyle Pomerleau acknowledged earlier this year.

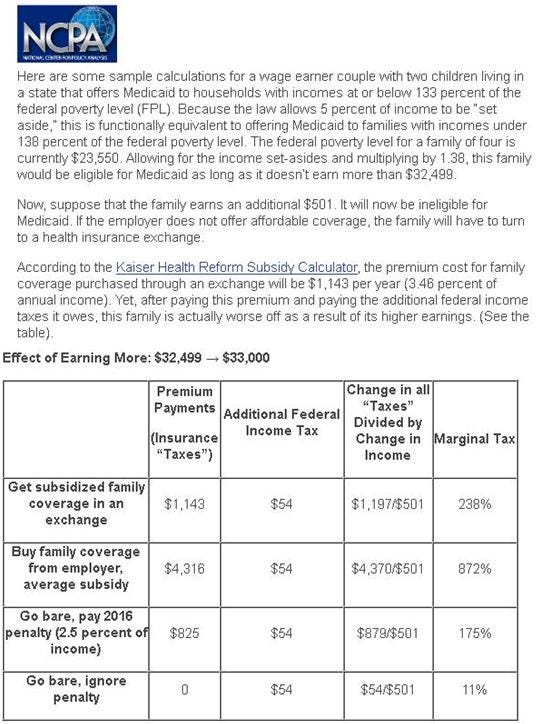

The same incentive is also created by the health insurance subsidies under the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) law.

One study that looked at the largest public health insurance disenrollment in U.S. history, which occurred in Tennessee in 2005, found that when people were taken off the public insurance rolls, they sought and obtained jobs so they could get health insurance coverage through their employer. The researchers predict that, because the Obamacare law significantly enlarges publicly subsidized health insurance coverage, almost a million people may leave the labor force to obtain it.

The Congressional Budget Office has estimated that the federal health care law will cut full-time employment by over two million people, concluding that “For some people, the availability of exchange subsidies under the ACA [Affordable Care Act] will reduce incentives to work both through a substitution effect and through an income effect. The former arises because subsidies decline with rising income (and increase as income falls), thus making work less attractive. As a result, some people will choose not to work or will work less -- thus substituting other activities for work. The income effect arises because subsidies increase available resources -- similar to giving people greater income -- thereby allowing some people to maintain the same standard of living while working less.” It has also stated “CBO estimates that the ACA will reduce the total number of hours worked, on net, by about 1.5 percent to 2.0 percent during the period from 2017 to 2024, almost entirely because workers will choose to supply less labor … For example, under the ACA, health insurance subsidies are provided to some people with low income and are phased out as their income rises; as a result, a portion of the added income from working more would be offset by a loss of some or all of the subsidies, which represents an implicit tax on earnings.”

One local news station examined the government programs that are available to a single mother of two making $19,000 a year in Pennsylvania and found that $81,589 in government assistance was available to her per year.

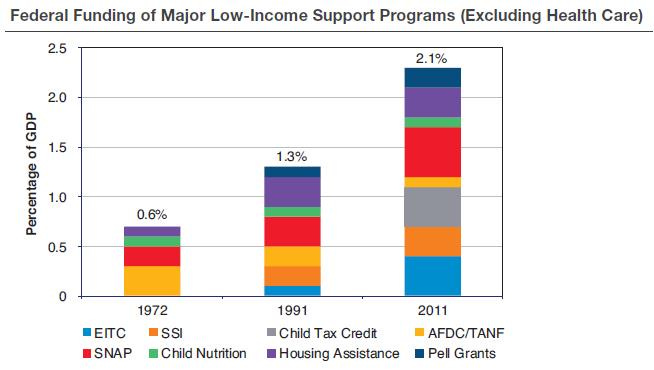

The following chart shows the growth in federal programs for those with low-incomes.

The percentage of tax filers participating in those programs has also grown significantly.

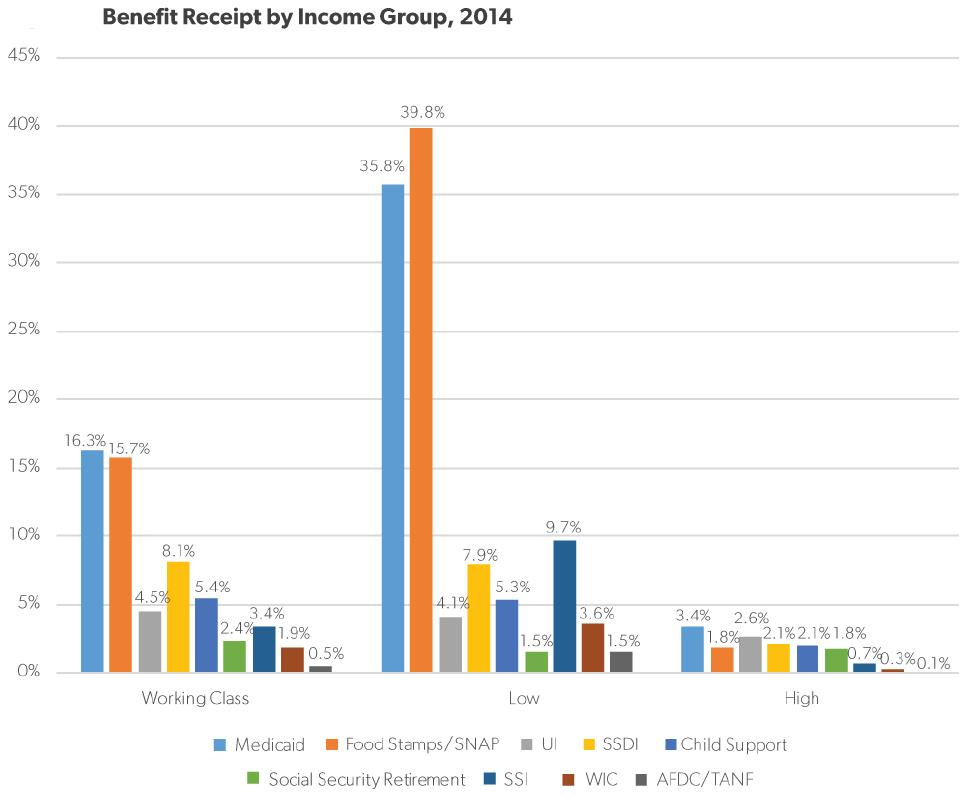

The following charts show participation in major low-income support programs by income group today and over time.

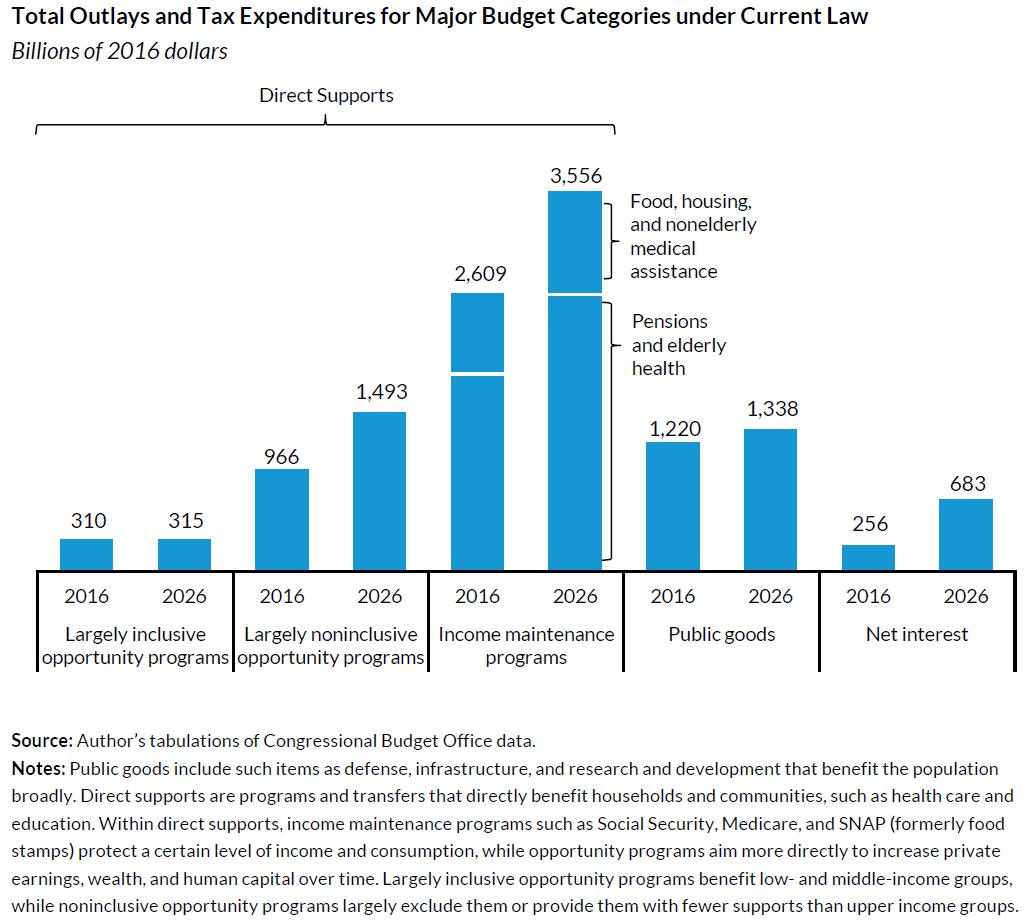

As Eugene Steuerle has pointed out, “the few [federal] programs that attempt to promote opportunity, such as work incentives and education, are scheduled to decline in the future and take a smaller share of available federal government resources,” whereas “[i]ncome maintenance programs, driven chiefly by health care and retiree benefits, [will] dominate the budget,” and “many [of such programs] have embedded in them negative work incentives through sometimes steep, sometimes modest, means testing or through signaling households to drop out of the labor force in what might easily be considered late-middle age as measured by remaining life expectancy and good health.”

Researchers investigated the long-term effect of cash assistance for beneficiaries and their children by following up, after four decades, with participants in the Seattle-Denver Income Maintenance Experiment. Treated families in this randomized experiment received thousands of dollars per year in extra government benefits for three or five years in the 1970’s. The researchers found evidence of significant effects on adults decades after the experiment ended. On average, treatment decreased the probability that participants work in a given year by 3.3 percentage points, and decreased average annual earnings by $1,800. Treated adults were also 6.3 percentage points (20% of the mean) more likely to apply for disability benefits (either SSDI or SSI). These effects for adults are large relative to the cash assistance received: for every $1 in additional government transfers, the researchers found that individuals earn discounted lifetime earnings that are $4.50 lower.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll conclude with more data on the large size and scope of government benefits programs, which discourage work.