Mismeasuring Economic Inequality – Part 12

The perverse incentives not to work caused by an obscure government benefits system.

In previous essays in this series we explored how official government measures of economic inequality obscure the size and extent of the government’s benefits system. In this essay, we’ll examine how that large and extensive government benefits system incentivizes people not to work and to leave the labor force.

As Phil Gramm, Robert Ekelund, and John Early write in their book The Myth of American Inequality: How Government Biases Policy Debate:

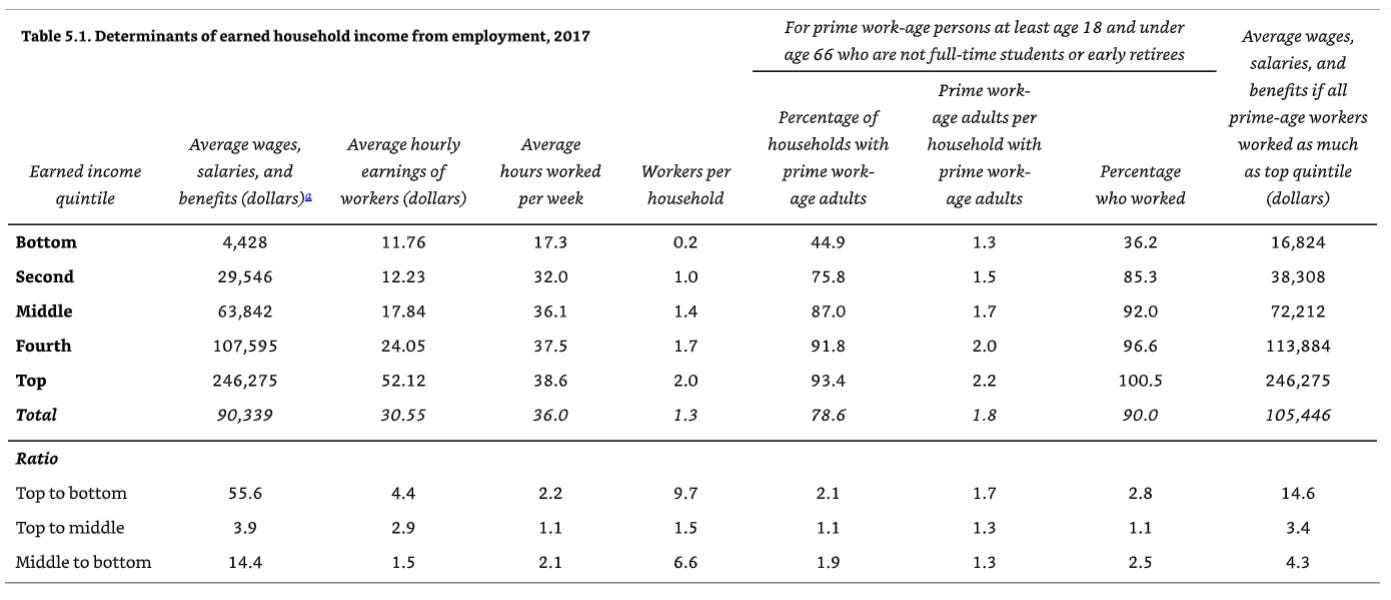

The average second- and middle-quintile households worked more and earned more than those in the bottom quintile, and yet, extraordinarily, the bottom 60 percent of American households all received essentially the same income when we count all transfer payments received and taxes paid and adjust that income for household size. This virtual equality of incomes after transfer payments and taxes in the lowest 60 percent of households is the result of two factors. First, inflation-adjusted transfer payments have exploded by 269 percent per bottom-quintile household since funding for the War on Poverty ramped up in 1967. Second, the tax burden has been reduced for low-income households and raised for higher-income households. Adjustments for household size make this income equality even more pronounced … Americans have tended to believe that people become rich because they work hard and are smart, but it is hard to see how a middle-income family with two adults both working would not resent the fact that other prime work-age people who are not working at all are just about as well off as they are … It is perfectly legitimate to debate how much income redistribution is appropriate in a free society. Those debates have a long and rich history, but it is much harder to argue that the top quintile of households gets too much and the bottom quintile gets too little when the top gets 4.0 times as much rather than the official Census measure of 16.7 times as much. When household income is adjusted for household size, it becomes even more difficult to claim that Americans suffer from “obscene” income inequality. In fact, a real question can be raised as to the fairness of current income redistribution policies that, after adjusting for household size, provide the average bottom-quintile household with about as many resources as the second and middle quintiles, even though prime work-age persons in the bottom quintile are less than half as likely to work and work only about half as many hours when they do work … Except for a very few individual outliers who have special needs that income redistribution cannot meet, America’s poverty program has virtually eliminated most poverty and raised most households to middle-income levels. But in another sense, the War on Poverty has been an abject failure because it has failed in President Lyndon Johnson’s second main objective: “to give people a chance … to allow them to develop and use their capacities.” The explosion in transfer payments to low-income Americans since 1967 has induced twice as many prime work-age adults among the poor to stop working and accept government subsidies, exchanging development and use of their capabilities for idleness … The driving forces producing the growth in earned-income inequality are the decoupling of low-income households from the workforce, the increase in educational attainment at higher levels, the dramatic rise in the value of that education, the increase in economic participation for women, and the rise of the super two-earner household … The most significant finding shown in Table 5.1 is that among prime work-age persons in the bottom quintile in 2017, only 36 percent were actually working, compared with more than 90 percent for households in the middle and higher quintiles.

[T]he average hourly earnings of the top quintile are only 4.4 times larger than the average earnings of the bottom quintile. That gap in total employment income as compared to average hourly earnings resulted from the fact that only 45 percent of bottom-quintile households had a prime work-age person, and only 36 percent of the prime work-age persons in the bottom quintile actually worked … For the people who were employed in the top quintile, the average number of hours worked during a week was almost 39. But for the 36 percent of prime work-age persons in the bottom quintile who were employed, the average number of hours worked per week was only 17 … The most significant factor in the growth of earned-income inequality in the last fifty years has been the sharp drop in the proportion of prime work-age persons who worked in the bottom two quintiles. In 1967, 68 percent of prime work-age adults in the bottom quintile had jobs, but by 2017 that percentage had dropped by almost half to 36 percent … At the same time, the proportion of prime work-age persons working in the top three quintiles of households increased by 7 percent, largely from an increase in the employment of women. The huge drop in work effort among lower-income households between 1967 and 2017 cannot be explained by any reduced demand for labor or rise in unemployment. The overall unemployment rates in both 1967 and 2017 were almost identical, and both were among the lowest unemployment rates during the entire fifty-year period. Among individuals who did work in 2017, those in the bottom quintile, on average, put in far fewer hours than working individuals in the other quintiles—only 17.3 hours per week. That was up 4.6 hours from only 12.7 hours worked in 1967, but the other 80 percent of the population increased their average weekly hours of work by even more, 7.8 hours, working on average 36.0 hours per week. Clearly, one reason for the rise in earned-income inequality was that the proportion of prime work-age persons in lower-income households who were working declined, while the proportion working in higher-income households increased. Earned income inequality rose still more because the increase in hours worked by workers in higher-income households was two-thirds greater than the increase in lower-income households. Only one structural change can explain the major decoupling of prime work-age persons in low-income households from the world of work: the near quadrupling (in constant dollars) of government transfer payments to lower-income households. In 2017, transfer payments increased the average bottom-quintile household’s income after transfers and taxes to $49,613—only $4,908 of which was earned income. The average income after transfers and taxes for the bottom quintile was only 8 percent less than the average for the second quintile and 24 percent less than the average for the middle quintile. There has been only one significant attempt to reverse this fifty-year trend of reduced work and increasing dependency. The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-193), or simply the Welfare Reform of 1996, was a bipartisan effort by President Bill Clinton and a Republican Congress. It replaced the Aid to Families with Dependent Children transfer payments with the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. Both the old and the new programs served only households with children, about 90 percent of which were headed by a single mother. The welfare reform endeavored to wean these families off welfare and build their self-reliance by creating stronger requirements for work or training. It also set more stringent time limits on receiving aid. The 1996 reforms were successful. The number of families receiving payments declined by more than half. Much of the decline was the result of beneficiaries finding employment. As a result, employment among low-income single parents rose.18 Poverty for single-mother families declined and has continued to remain lower than it was before the reforms. Single-mother poverty also declined relative to poverty for other types of families and has remained lower ever since … The significant and quantifiable effects from the initial reform efforts were overwhelmed by subsequent expansion of other transfer payments … [T]he unemployment rate in 2017 was actually 18.5 percent lower than in 1996. Yet the proportion of the population receiving food stamps was 36.7 percent greater. Over the same period, the proportion of the prime work-age persons receiving Social Security Disability Insurance benefits increased by almost 50 percent. This increase in disability beneficiaries occurred when work-related accidents had fallen to an all-time low, medical advances had reduced the impact of many disabilities, and the Americans with Disabilities Act had forced employers to make the workplace more accommodating to those with disabilities … USDA rewarded and publicized state social service agencies for their success in overcoming the “mountain pride” of potential beneficiaries “who wished not to rely on others.” … In the fifty years after the funding for the War on Poverty ramped up in 1967, the bottom quintile’s share of the nation’s earned income fell by more than half. Incredibly, its share in 2017 was 40 percent below what it had been in 1947. The second quintile’s earned-income share fell by more than a third. These incredible drops in income share were largely the result of a massive decline in the proportion of people in the bottom quintile of households who worked and a smaller decline in the proportion in the second quintile who worked. Nevertheless, the standard of living among lower-income households improved substantially from massive government subsidies. Between 1967 and 2017, these subsidies raised the bottom quintile’s share of total income after transfers and taxes by more than a third and the second quintile’s share by 10 percent. Dependence on government subsidies increased dramatically. Low-income Americans became less likely to “develop and use their capacities” to earn a living, and measures of inequality for earned income rose … Despite government’s stated intention to avoid dependence, government policies have created more dependence and, in the process, dramatically increased the inequality of earned income … The average household with prime work-age adults in the bottom quintile earned $6,941, paid $3,512 in taxes, and received $45,377 in transfer payments, resulting in $49,488 of income after taxes. In an average household in the second quintile, more than twice as many of the prime work-age adults worked (80.8 percent versus 33.0 percent for the bottom quintile). And, on average, they worked almost twice as many hours per week (33.0 versus 18.5). As a result, they earned $31,811, or $24,870 more than the average bottom-quintile household. But because they earned so much more money, the average second-quintile household was not eligible for $18,972 in transfer payments that the average bottom-quintile household received and paid $4,212 more in taxes—mostly additional payroll taxes. So, after working more than four times as much, the average second-quintile household had only $1,686 more money for living than the average bottom-quintile household. From the additional income that they earned compared with the bottom quintile, the average second-quintile household got to keep only 7 cents of every additional dollar, an extremely small economic incentive to work more. The average middle-quintile household earned $59,512 more than the average for the bottom quintile but lost $32,444 in transfer payments and $14,524 more in taxes, keeping only 21 cents of every additional dollar earned.

About half of what economic inequality exists today in America is a function of the decreased work engaged in by many of those in lower income quintiles, especially prime working-age people:

The most significant factor affecting earned-income inequality was the dramatic enlargement of the difference in the amount of work performed by members of households. The proportion of prime work-age persons in the bottom quintile who worked dropped by half. A smaller decline also occurred in the second quintile. In the middle and higher income quintiles, the change was in the opposite direction, with increases in the proportion of prime work-age people who worked … [T]he difference in the amount of work performed by households between 1967 and 2017 accounted for almost half of the total Gini coefficient increase of 26.6 percent.

As a report in the New York Times recently concluded, “Many men, in particular, have decided that low-wage work will not improve their lives, in part because deep changes in American society have made it easier for them to live without working. These changes include the availability of federal disability benefits; the decline of marriage, which means fewer men provide for children; and the rise of the Internet, which has reduced the isolation of unemployment.” Over time, people from poor families, especially those from single parent households, have come to have fewer prospects for upward mobility.

This was not the original intent of those who created the original welfare system. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, one of the principal founders of the modern welfare state, believed that a dependence on welfare destroyed the human spirit. He stated the following in his January 4, 1935, Annual Message to Congress: “The lessons of history, confirmed by the evidence immediately before me, show conclusively that continued dependence upon relief induces a spiritual and moral disintegration fundamentally destructive to the national fiber. To dole out relief in this way is to administer a narcotic, a subtle destroyer of the human spirit. It is inimical to the dictates of sound policy. It is in violation of the traditions of America. Work must be found for able-bodied but destitute workers. The Federal Government must and shall quit this business of relief.” In her biography of Frances Perkins, The Woman Behind the New Deal: The Life of Frances Perkins, FDR’s Secretary of Labor and His Moral Conscience, Kirstin Downey writes “By October [1935] the effort had expanded into an alphabet soup of relief agencies—the Federal Employment Relief Administration, or FERA; the Civil Works Administration or Program, known as CWA; and the Public Works Administration, or PWA. The programs contained relief features, but, because Roosevelt favored paid work rather than handouts, they involved creating jobs, so that people earned pay for accomplishing tasks. Roosevelt later explained that ‘to dole out relief… is to administer a narcotic, a subtle destroyer of the human spirit.’” And as another Franklin (Benjamin Franklin) wrote, “I am for doing good to the poor, but I differ in opinion of the means. I think the best way of doing good to the poor, is not making them easy in poverty, but leading or driving them out of it.” Contrary to popular belief, “From the earliest colonial days, local governments took responsibility for their poor. However, able-bodied men and women generally were not supported by the taxpayers unless they worked. They would sometimes be placed in group homes that provided them with food and shelter in exchange for labor. Only those who were too young, old, weak, or sick and who had no friends or family to help them were taken care of in idleness.”

As the authors of The Myth of American Inequality write:

The current welfare system was created in the 1930s during the Great Depression. At the time President Franklin Roosevelt explicitly warned, “Work must be found for able-bodied but destitute workers. The Federal Government must and shall quit this business of relief.” When President Lyndon Johnson greatly expanded welfare with his Great Society programs in the mid-1960s, he likewise warned, “The War on Poverty is not a struggle simply to support people, to make them dependent on the generosity of others. It is an effort to allow them to develop and use their capacities.” All Americans have been poorly served by the failure of the government to live up to those pledges. In the bottom two income quintiles today, eighteen million prime work-age adults live in whole or in significant measure on government transfer payments. They have been induced to give up their opportunity to “develop and use their capacities,” as President Johnson promised. Today public assistance continues to grow faster than the earned income of taxpayers, with the average nonretired household in the bottom quintile receiving more than $41,000 in government transfer payments, while employers cannot find people willing to work in their eleven million vacant jobs … Most importantly, by providing transfer payments that allow nonworkers to live a middle-income lifestyle, public policy has induced millions of prime work-age persons to drop out of the labor market and, as a result, to lose access to the opportunities for economic advancement that are generated by the American economy … The bottom 20 percent of households with one or more prime work-age earners and no Social Security retirement benefits received on average more than $41,000 in government transfer payments, which enabled them to consume at middle-income levels. At these high subsidy levels, most beneficiaries have little or no incentive to take a job since they are receiving about as much for not working as they could earn working … Unfortunately, more Americans continue to drop out the labor force as transfer payments increase. We have all seen an additional significant decline in labor force participation produced by the explosion of transfer payments in response to the COVID shutdown. After transfer payments to households jumped 30 percent from the first quarter of 2019 to the third quarter of 2021,18 no one should have been surprised that over the same period 1.5 percent of the civilian labor force, or about 2.5 million people, simply dropped out of the labor force.

As Nicholas Eberstadt explains:

Although our nation has never been so rich, never have so many been living on so-called poverty benefits. Although health and longevity for young and middle-aged parents are vastly better than in earlier times, never have so many children been living as if orphaned, with just a mother, just a father, or sometimes just grandparents. Although our economy celebrated “full employment” on the eve of the pandemic, our work rate for prime-age American men mirrored levels from the tail end of the Great Depression. And although our national net worth has been soaring for decades, net worth for households in the bottom half was actually lower when the pandemic hit than when the Berlin Wall fell, 30 years earlier.

(The similar disincentives to work created by foreign aid programs are described in the excellent documentary Poverty, Inc.)

In the end, this official ignoring of income simply subsidizes non-work. As Watt Weidinger writes:

Never shy about lampooning government dysfunction, Ronald Reagan famously said that if you want more of something, subsidize it. But even the Gipper couldn’t have imagined today’s growing zeal to subsidize getting more people on government benefits, which undermines work and leaves too many on the sidelines of the economy. Welfare programs achieve that dubious distinction when they ignore the value of other government benefits in determining eligibility … The problem involves “income disregard” policies that ignore the value of government benefits in calculating eligibility for welfare programs meant to help low-income individuals and families. Ignoring such income makes benefit recipients appear artificially poorer than someone with the same income from work. That encourages benefit collection over work, and artificially expands safety net programs meant for those with low incomes. During the pandemic, temporary federal laws mandated welfare programs ignore a record $1.4 trillion in stimulus checks, expanded unemployment benefits, and enhanced child tax credit payments when assessing whether applicants were poor enough to qualify. That meant a household with two adults and two young children could collect more than $67,000 in pandemic benefits without a penny being counted in determining its eligibility for Medicaid. Two-thirds of that amount, or nearly $47,000, would have been similarly ignored when the family applied for food stamps. Instead of recognizing those significant benefits, income disregard policies could make them appear to have no income at all. The results were predictable: income disregards contributed to Medicaid and food stamp rolls soaring to record highs. Between February 2020 (the month before the pandemic struck) and a recent peak in April 2023, Medicaid caseloads soared from 64.1 million to 87.1 million, an increase of 36 percent. Similarly, food stamp caseloads rose from 36.9 million in February 2020 to a high of 42.8 million in January 2023. Caseloads have since declined as pandemic expansions expired. Income disregards were embedded in welfare programs long before the pandemic and remain there in its wake. In 2017, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) found major programs ignore multiple sources of benefit income. Then as now, Medicaid fails to count earned income tax credit (EITC) payments, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families welfare checks, food stamp benefits, and Supplemental Security Income payments. The GAO could have added refundable child tax credit (CTC) payments to that list. Those disregarded benefits collectively provided over $340 billion in support to families in FY 2022.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll contrast the results of the COVID-19-related expansions of government benefits with the work requirements of the 1996 Welfare Reform Act.