Mismeasuring Economic Inequality – Part 13

Contrasting the results of the COVID-19-related expansions of government benefits with the work requirements of the 1996 Welfare Reform Act.

Robert Doar and Matt Weidinger described in the Wall Street Journal the negative effects of the Biden Administration and congressional Democrats’ supported bill to remove work and education requirements for welfare in response to the COVID-19 pandemic as follows:

Universal basic income is about to arrive in America. Congressional Democrats’ $1.9 trillion stimulus bill provides for no-strings attached checks, limited only to parents of children under 18. This UBI for parents is billed as pandemic relief, but its real purpose is to put a stake in the heart of work-based welfare reform. Supporters blandly describe their plan as “Child Tax Credit improvements for 2021.” It would replace today’s annual child tax credit, which tops out at $2,000, with more-generous “child allowances,” payable monthly. Those allowances are federal payments of $3,600 (or $300 a month) for each child under 6 and $3,000 ($250 a month) for older children. The current credit increases with income from work; the new one would provide the same large payments to all. Under the guise of pandemic relief, the federal government would give a nonworking single parent with two preschool-age children and one in grade school $850 a month. This would come on top of other government benefits, including $680 a month in food stamps, amounting to $18,360 in combined annual income. That’s the equivalent, without accounting for taxes, of working 28 hours a week at $12.50 an hour. On top of that, the family would receive health insurance from Medicaid, and it may also receive housing and child-care assistance. Government benefits to nonworking households that are this generous are bound to reduce employment. The bill would provide the new benefit for only one year, but the Washington Post reports that “congressional Democrats and White House officials have said they would push for the policy to be made permanent later in the year.” Under current law, federal cash assistance to poor families flows through state social-services agencies, which require recipients to work, look for work, or at least engage in some activity designed to help them become employed. UBI for parents is designed to circumvent these requirements. If enacted it will more than double the government-provided cash assistance to households headed by single mothers, creating a perverse incentive for the unmarried poor to have more children. That would lead to more poverty, not less. Unlike existing benefits, UBI for parents also avoids efforts to seek and collect child-support payments from parents who don’t live with their kids. That’s unfortunate, because efforts to collect child support have led to increased income for families in need and greater emotional connection between absent dads and their children. If all this sounds vaguely familiar, it should. Sending monthly checks to nonworking parents was exactly how welfare used to work until 1996, when President Clinton signed the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act, for which Sen. Joe Biden voted. That law requires parents to work or train in exchange for welfare benefits and offered additional child care and other support to help them go to work.

One of the originators the child tax credit idea wrote the following in the Wall Street Journal in 2022:

Handing a family $3,000, $6,000 or even $9,000 in cash is certainly palliative, but does it truly improve long-term living standards? No. On the contrary, recent studies estimating the economic effects of the proposed expansion suggest that it would cause people to leave the workforce, reduce work effort, and lower capital investment, ultimately shrinking economic output. A recent study by economists at the University of Chicago determined that without any changes in behavior, expanding the credit would reduce child poverty by 34% and “deep” child poverty—families whose income is less than half the poverty level—by 39%. But those gains would come at a cost: the diminution of the workforce by 1.5 million people. Consequently, fewer working parents would diminish the child tax credit’s impact on reducing child poverty by more than a third, to 22% from the initial estimate of 34%. A new study by Congress’s Joint Committee on Taxation assesses both the budgetary and economic impact of expanding the child tax credit. First, JCT determined that it would be a budget-buster, reducing revenue by more than $1.3 trillion over the next decade … The child tax credit is a drain not only on the federal budget but on the nation’s economy. JCT’s economic models predict that over a decade the policy would reduce the labor supply by 0.2% and reduce the amount of capital by 0.4%. As a result of the reduced supply of labor and capital investment, gross domestic product would shrink by 0.2%.

As described in the Wall Street Journal in December, 2022:

For the past two years, the Administration has repeatedly extended the national public-health emergency for no ostensible purpose other than to expand the welfare rolls. President Biden in September declared the pandemic over, but the Health and Human Services Department says it plans to extend the emergency until at least mid-April. The Families First Coronavirus Response Act of 2020 increased federal Medicaid funding to states on the condition that they don’t kick ineligible beneficiaries off their rolls as long as a public-health emergency is in effect. The law also increased food-stamp benefits and waived work requirements for able-bodied, working-age adults during the emergency. Since February 2020, Medicaid enrollment has ballooned by 23 million to an all-time high of 97 million. By comparison, Medicaid grew by 14 million between 2013, just before the ObamaCare expansion took effect, and the start of the pandemic. About 21 million Medicaid recipients don’t currently meet eligibility requirements, according to the Foundation for Government Accountability … The same is true for food stamps whose rolls have swelled by nearly five million nationwide, or about 13%, during the pandemic owing chiefly to the emergency suspension of work requirements, even as unemployment has reached pre-pandemic levels. Anyone who wants a job can get one, but expanded transfer payments have reduced the incentive to look.

Further, as Angela Rachidi reports:

Most Americans have never heard of the Thrifty Food Plan, but President Joe Biden’s US Department of Agriculture (USDA) used a routine re-evaluation of it to bypass Congress and increase government spending on a key safety net program. The Congressional Budget Office estimated the cost at $200 billion over the next 10 years, adding to an already overstretched federal budget. Now, the Government Accountability Office (GAO)—Congress’s nonpartisan watchdog—has confirmed in two reports that the USDA acted improperly.

The approach of massively increasing government benefits during the COVID-19 pandemic led to fraud of historic proportions. As reported in the Wall Street Journal:

The Labor Department’s Inspector General has updated its estimates of fraud in pandemic-era unemployment benefits, and it’s hard to know what’s worse: the shoddy systems that allowed crooks to bilk taxpayers, or the Biden Administration’s refusal to do anything about it. The IG first alerted Labor to the scope of the problem with reports in February and June last year, identifying $16 billion in potentially fraudulent payouts to large and small operators of unemployment scams. A new IG memo last week identifies $30 billion more in fraudulent payments—for a total of $45.6 billion … The IG blames the growing numbers on the Labor Department’s Employment and Training Administration (ETA), which is responsible for unemployment benefits. The memo says the IG in February 2021 identified high-risk areas and recommended ETA work with state agencies to develop fraud controls, as well as coax Congress to pass legislation requiring state agencies to cross-match high-risk areas. Yet 19 months later, the memo reports, “ETA has not taken sufficient action” which “significantly increases the risk of even more [unemployment] payments to ineligible claimants.”

As Matt Weidinger writes:

A scathing report released by the California State Auditor on August 24 finds that the state’s Economic Development Department (EDD) continues to mismanage the unemployment insurance (UI) program, resulting in “a substantial risk of serious detriment to the State and its residents.” The California Labor and Workforce Development Agency, which oversees EDD, was formerly led by Julie Su, whom President Biden has nominated to be the US Secretary of Labor. In addition to UI, EDD administered over $130 billion in federal unemployment benefits during the pandemic. In January 2021, Su admitted that 10 percent of unemployment benefits EDD had administered to that point during the pandemic were fraudulent, while another 17 percent were potentially fraudulent.

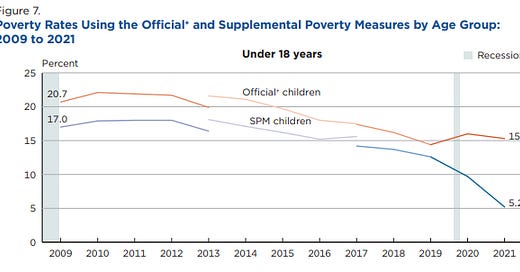

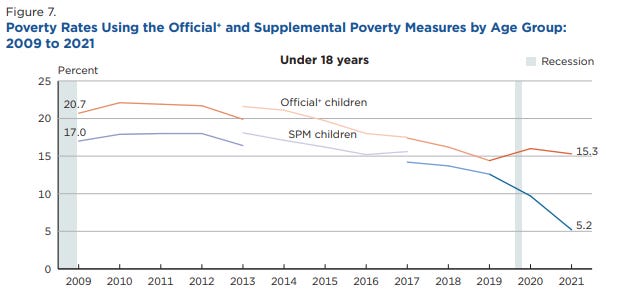

The cavalier COVID-era approach to federal benefits is the polar opposite of the work requirements approach of the federal welfare reforms enacted in 1996. As Angela Rachidi reports, welfare reform and work requirements reduced child poverty:

[L]ong-term declines in child poverty were mostly driven by increased employment among low-income families largely due to conservative-led policy changes in the 1990s—underscoring the importance of a safety net that supports work, rather than discourages it.

The long-term trend is visible in another study published … through Child Trends using a slightly different version of the Census Bureau’s supplemental poverty measure where the threshold adjusts for inflation rather than expenditures. The Child Trends report showed a child poverty decline of 59 percent from 1993 to 2019 reaching an all-time low of 11.4 percent before pandemic-related aid.

The child poverty trends documented by these recent reports are a policy success, but not for the reasons hitting the headlines. Opinion writers in the Washington Post concluded that the child poverty trends “undercut conservative arguments that such government help must be accompanied with work requirements,” but only after they also argued that, “much of the credit [for the poverty decline] goes to the earned income tax credit and the child tax credit.” What the authors fail to acknowledge, however, is that the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and child tax credit have always had a work requirement, except for a temporary six-month expansion to the child tax credit in 2021. Much of the reason why these programs have been so effective at lifting children out of poverty is because they have encouraged many low-income parents to work. Commentators mislead the public when they suggest that the child poverty declines are due to expansions in government benefits alone and that conservative policies played no role. Conservative-led welfare reform in 1996 replaced a no-strings-attached cash welfare system with a system that conditioned assistance on work. Combined with expansions to the EITC in 1993, welfare reform led to dramatic increases in labor force participation among single mothers, which translated into increased income and lower poverty.

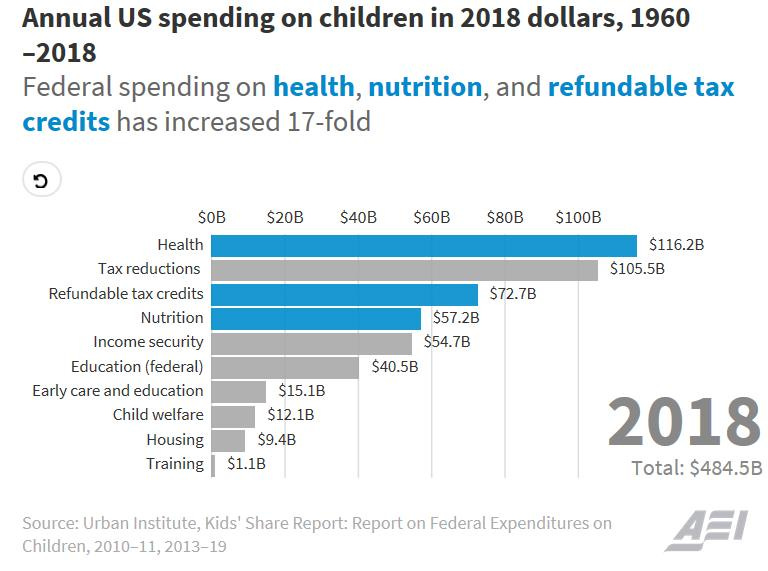

In any case, federal expenditures on low-income children have increased dramatically in recent decades. These spending increases have especially targeted three areas of support -- health, refundable tax credits, and nutrition support -- through means-tested programs. Federal spending on health, nutrition, and refundable tax credits for low-income children was almost nonexistent in 1960, but has since increased 17-fold, surpassing all other categories by 2018, with the exception of tax reductions stemming from the dependent deduction.

Children are now consuming much more as a result of these spending increases.

And the poverty gap between children of different races in the US has decreased substantially in recent years, as research has shown since as early as 2016.

Data from the Columbia Poverty Center reveal that the poverty gap between Black and White children decreased by 22.1 percentage points (58.1 percent) between 1970 and 2016.

Between white and Hispanic children, the poverty gap decreased by 16.2 percentage points (50.9 percent) during the same time period.

Regarding the 1996 federal welfare reforms that conditioned benefits on work requirements, researchers at the CATO Institute also found that the work requirements in federal welfare benefits significantly increased employment and decreased poverty:

Our research is the first to use comprehensive income data to examine changes in poverty over time in the United States. By “comprehensive,” we mean survey data linked to an extensive set of administrative tax and program records, such as those of the Comprehensive Income Dataset (CID) project. Using the CID allowed us to correct for measurement error in survey‐reported income while continuing to use the family unit identified using surveys as the group sharing that income. We focused on individuals in single‐parent families in 1995 and 2016, providing a two‐decade‐plus assessment of the change in poverty for this policy‐relevant subpopulation. Single parents were greatly affected by welfare reform policies in the 1990s that imposed work requirements in the main cash welfare program and rewarded work through refundable tax credits. Single parents are also targeted by many current and proposed policies, including a 2021 proposal to replace the existing child tax credit with a child allowance for all low‐ and middle‐income families regardless of earnings. We find that single‐parent‐family poverty, after accounting for taxes and nonmedical in‐kind transfers, declined by 62 percent between 1995 and 2016 using the CID.

The 1996 federal welfare reforms also appear to have increased happiness among the beneficiaries of its work requirements. As reported in a study by the American Enterprise Institute:

We investigate how material well-being has changed over time for single mother headed families—the primary group affected by welfare reform and other policy changes of the 1990s. We focus on consumption as well as other indicators including components of consumption, measures of housing quality, and health insurance coverage. The results provide strong evidence that the material circumstances of single mothers improved in the decades following welfare reform. The consumption of the most disadvantaged single mother headed families—those with low consumption or low education—rose noticeably over time and at a faster rate than for those in comparison groups.

The National Evaluation of Welfare to Work Strategies studied 11 different programs across the country that randomly assigned people to a program group that included a work requirement along with services or to a control group that had no requirement and no services. The researchers found that “Nearly all 11 programs increased how much people worked and how much they earned, relative to control group levels, but the four employment focused programs generally produced larger five-year gains in employment and earnings than did most of the seven education-focused programs.”

And as Angela Rachidi reports, “A new working paper by Jason Falk at the Congressional Budget Office provides evidence that work requirements remain effective at offsetting work disincentives in TANF, suggesting that they continue to be a relevant and useful policy tool. Falk studied changes to Alabama’s TANF policy that extended the work requirement to parents of children age 6 to 11 months, which previously had covered only parents of children 12 months or older. Falk found that the work requirement increased employment by a substantial 11 percentage points (29 percent) among mothers receiving TANF, mainly because they sought and found work earlier than mothers did prior to the change. He also found other positive effects, including overall reductions in TANF receipt (because the work requirement hastened TANF exists) and net increases in income (on average) based on projected employment and earnings. Specifically, Falk wrote: “I find that Alabama’s work requirement increases the employment rate by about 12 percentage points over the first year after families enter the program, which elevates average income by boosting earnings and tax credits.”

Finally, as Matt Weidinger writes, today, debates regarding reductions in welfare benefits that would accompany proposals for work requirements rarely mention previous surges in welfare benefit dispensation:

While the debate often focused on comparatively modest reductions in benefit receipt, it totally ignored significant and ongoing real increases in welfare benefit collection. Those real increases far exceed projected benefit reductions resulting from work requirement proposals, both now and in the years ahead. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that the House work requirements would have resulted in 275,000 fewer ABAWDs collecting food stamps each month and some 600,000 fewer receiving Medicaid over the next decade. Meanwhile, other CBO data—specifically its baseline projections for the number of current and expected future benefit recipients—show that both food stamp and Medicaid caseloads have recently grown many times faster than those would-be reductions. Before the pandemic started in March 2020, CBO projected that by the current fiscal year 2023 an average of 33.4 million individuals would collect food stamps each month. Yet in its latest projections issued last month, CBO now expects an average of 42.3 million to receive food stamps this year—an increase of almost 9 million compared with its 2020 estimate. That difference is more than the entire population of New York City. Similarly, before the pandemic CBO projected there would be an average of 74 million Medicaid recipients by this fiscal year. Meanwhile, last month CBO estimated an average of 94 million would receive Medicaid this year. That 20 million difference is more than the combined population of America’s five largest cities (New York, LA, Chicago, Houston, and Phoenix). Huge increases in benefit receipt are expected to long outlive the pandemic. Consider benefit receipt at the start of the next decade. CBO today projects that in fiscal year 2030 there will be 37.5 million food stamp recipients, or almost 7 million more than its pre-pandemic estimate of 30.7 million recipients for that year. It’s the same story with Medicaid. CBO today expects there will be 81 million Medicaid recipients in 2030—or 4 million more than the 77 million it forecast for that year before the pandemic struck.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll look at the “benefits cliff” as a disincentive to earn more income.