Mismeasuring Economic Inequality – Part 11

The role of charitable organizations in providing benefits in America.

In this essay, we’ll look at the role of charitable organizations in providing benefits in America.

In their book The Myth of American Inequality: How Government Biases Policy Debate, Phil Gramm, Robert Ekelund, and John Early write, regarding government benefit beneficiaries:

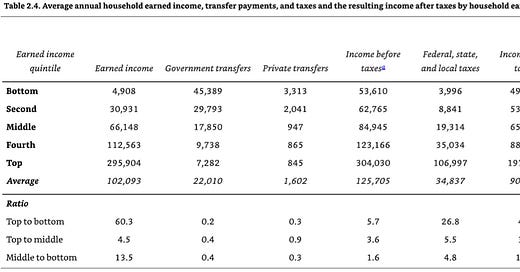

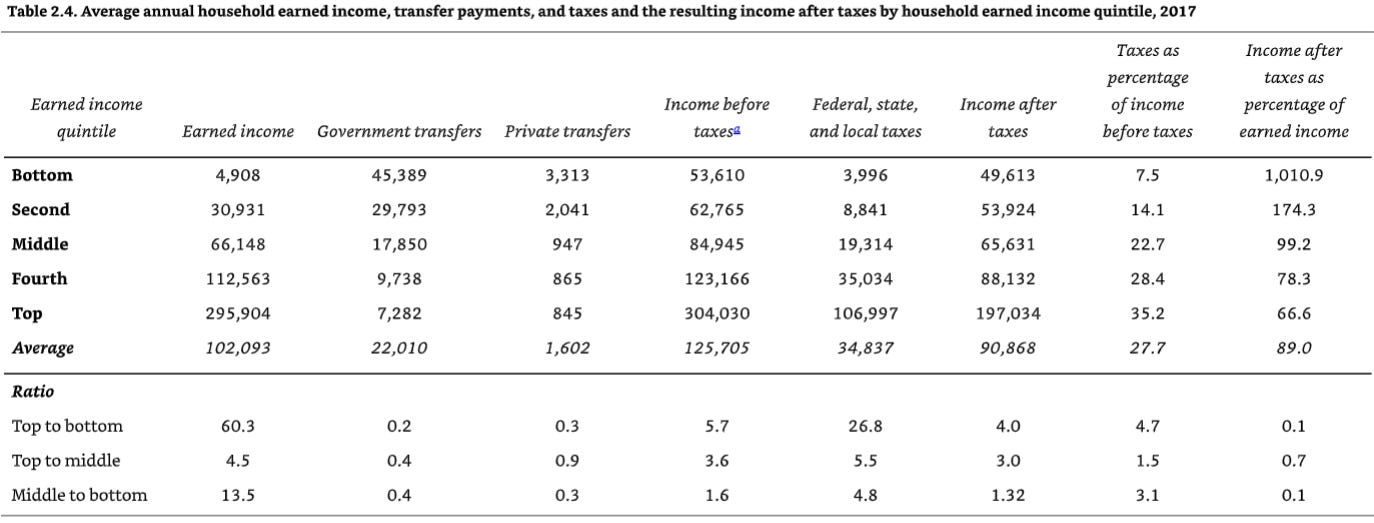

Some households received additional resources, such as help from charitable organizations, private educational assistance, child support from an absent parent, regular payments from family or friends, or alimony. Americans donated 1.44 percent of gross domestic product to charity, by far the highest rate for any nation. A little more than one-quarter of these charitable donations was directed to private households. Charitable assistance, family, and other sources for private transfers were relatively small, only about 7 percent as much as government transfers. Nevertheless, the bottom quintile received a meaningful average transfer of $3,313 per household from these sources (see Table 2.4).

After accounting for all income, non-cash welfare benefits like subsidized housing and Food Stamps, and also the large role played by charity in the America, the poorest 20% of Americans consume more goods and services than the national averages for all people in most affluent countries. This includes the majority of countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), including its European members. In other words, if the U.S. “poor” were a nation, it would be one of the world’s richest.

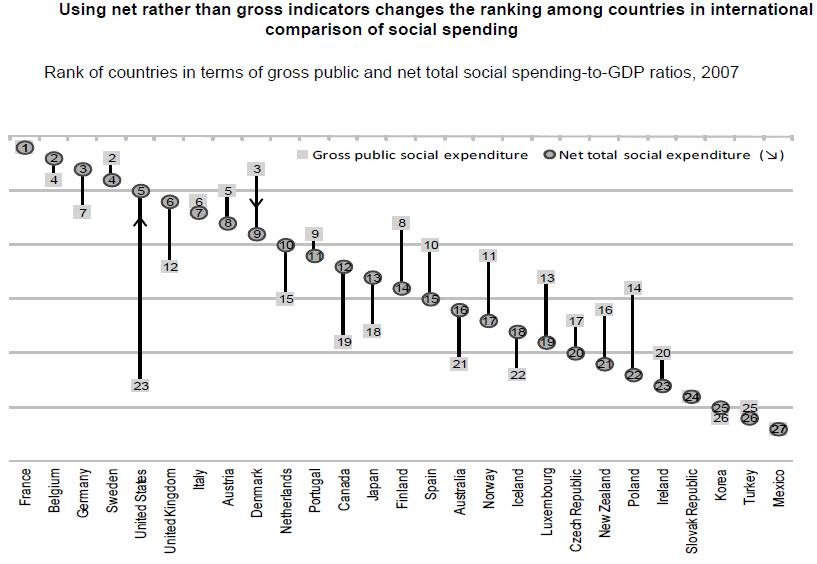

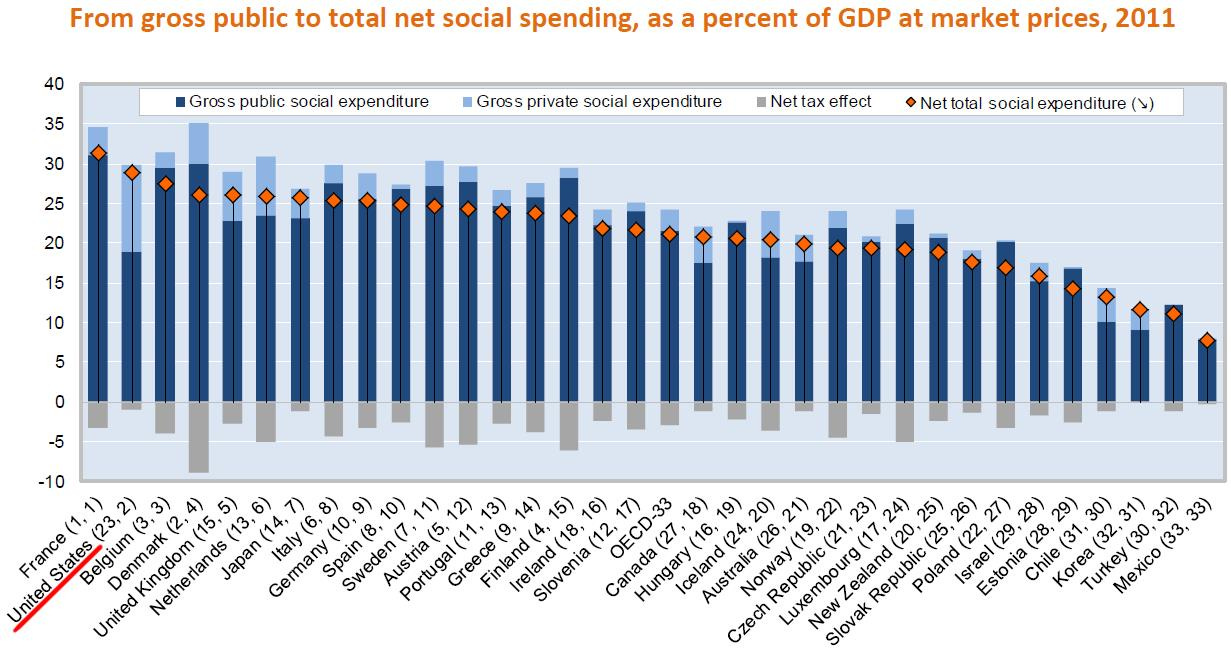

While the United States government may tax and spend a bit less on social welfare programs than other democracies, when you add in tax-based subsidy incentives and private social spending, the U.S. in 2007 ranked as the fifth highest social welfare spender in the world, just after Sweden.

By 2014, the U.S. ranked second in total social welfare spending.

At the same time, large government benefits programs crowd out private charitable giving generally. As the federal government takes more of what people earn and claims more responsibility for more people’s well-being, religious people, along with all other people, have less to spend on private charities.

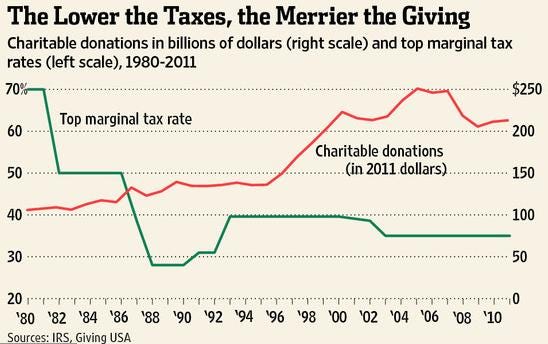

Higher tax rates also result in less charitable giving.

Researchers found that the philosophy of individualism (the habit of being self-reliant) is associated with both greater well-being and greater altruism. As one of the researchers described the results in the New York Times:

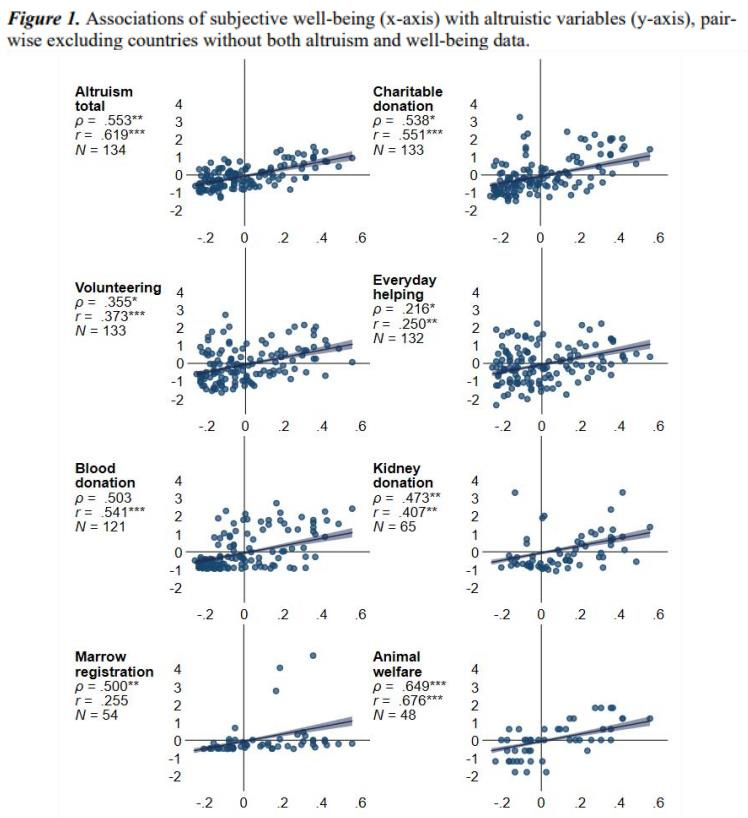

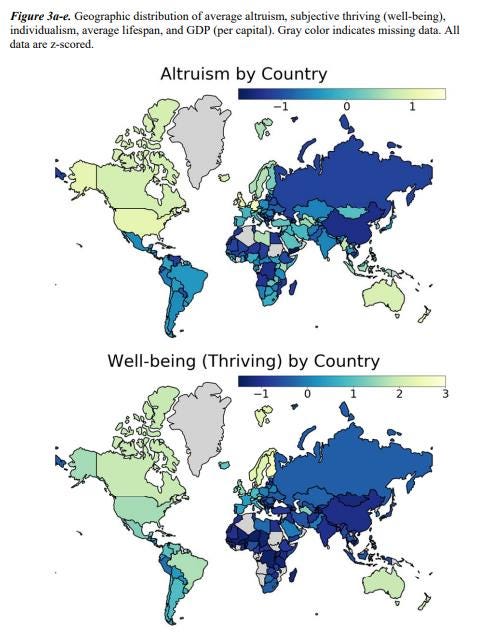

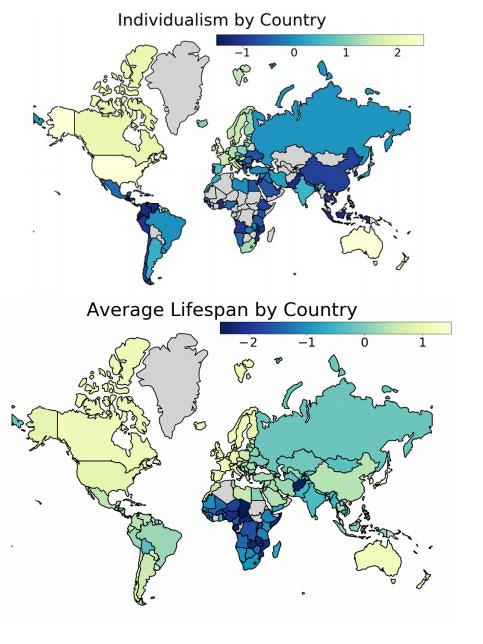

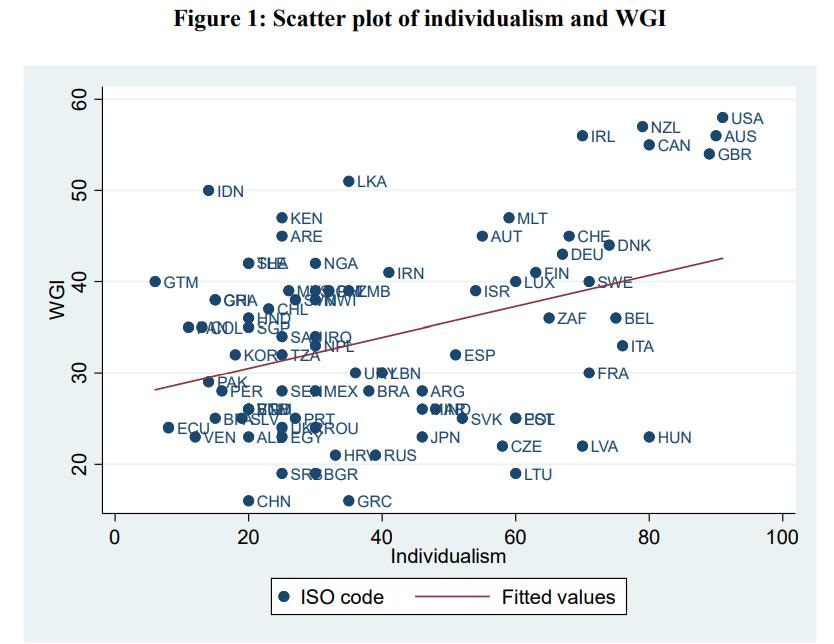

The United States is notable for its individualism. The results of several large surveys assessing the values held by the people of various nations consistently rank the United States as the world’s most individualist country. Individualism, as defined by behavioral scientists, means valuing autonomy, self-expression and the pursuit of personal goals rather than prioritizing the interests of the group … But new research suggests the opposite: When comparing countries, my colleagues and I found that greater levels of individualism were linked to more generosity — not less … For our research, we gathered data from 152 countries concerning seven distinct forms of altruism and generosity. The seven forms included three responses to survey questions administered by Gallup about giving money to charity, volunteering and helping strangers, and four pieces of objective data: per capita donations of blood, bone marrow and organs, and the humane treatment of nonhuman animals (as gauged by the Animal Protection Index). We found that countries that scored highly on one form of altruism tended to score highly on the others, too, suggesting that broad cultural factors were at play. When we looked for factors that were associated with altruism across nations, two in particular stood out: various measures of “flourishing” (including subjectively reported well-being and objective metrics of prosperity, literacy and longevity) and individualism. The fact that countries in which people are flourishing are also those in which people engage in greater altruism is in keeping with earlier research showing that people who report high levels of personal well-being tend to engage in more positive, generous social behaviors. That individualism was closely associated with altruism was more surprising. But even after statistically controlling for wealth, health, education and other variables, we found that in more individualist countries like the Netherlands, Bhutan and the United States, people were more altruistic across our seven indicators than were people in more collectivist cultures — even wealthy ones — like Ukraine, Croatia and China. On average, people in more individualist countries donate more money, more blood, more bone marrow and more organs. They more often help others in need and treat nonhuman animals more humanely. If individualism were equivalent to selfishness, none of this would make sense.

Other researchers from five different universities found that “Our empirical results, which hold with three different measures of individualism, show that individualism is indeed associated with higher levels of charitable giving.”

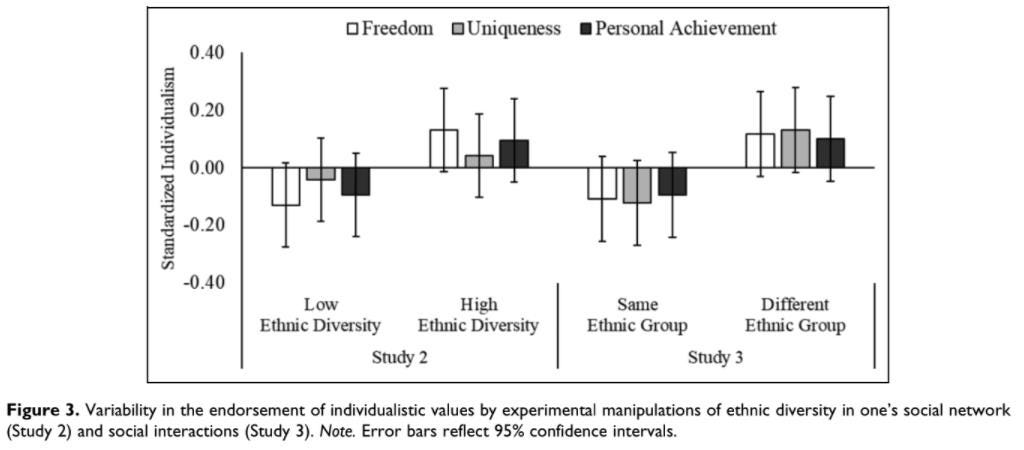

Researchers have found that greater racial and ethnic diversity within one’s social network tends to increase one’s adherence to the values of individualism, including individual autonomy and a greater preference for uniqueness, indicating that as America becomes more racially and ethnically diverse, its people will come to value individualism more, and loyalty to their racially and ethnically-defined in-group less, as interethnic contact involves weakened in-group boundaries. As the researchers reported:

In three studies, across different levels of measurement and analysis, we find converging evidence that ethnic diversity accompanies individualistic relational structures and increases the endorsement of individualistic values. Historical rates of ethnic diversity across different U.S. regions reveal this association (Study 1), as do individual-level reports of interethnic contact (Studies 2 and 3). The results of the forecasting model in Study 1 suggest that the trend toward increasing individualism will likely continue over the next several decades, assuming continuing growth in ethnic diversity … That is, future increases in ethnic diversity will likely be accompanied by an increasing societal emphasis on individualistic dimensions—for example, individual autonomy and a greater preference for uniqueness.

(Of course, the danger is that this tendency will be reversed if race-focused thinking that inculcates tribalism comes to hold sway.)

In the next essay in this series, we’ll examine the perverse incentives not to work caused by obscuring the extent of the government’s benefits system.

Wow, wow, wow, wow, wow. Howcum no one knows this stuff? The charts/graphs are overwhelmingly compelling. Many thanks once again.