In their book The Myth of American Inequality: How Government Biases Policy Debate, Phil Gramm, Robert Ekelund, and John Early point out that there is significant upward income mobility in America when measured by historical standards of well-being:

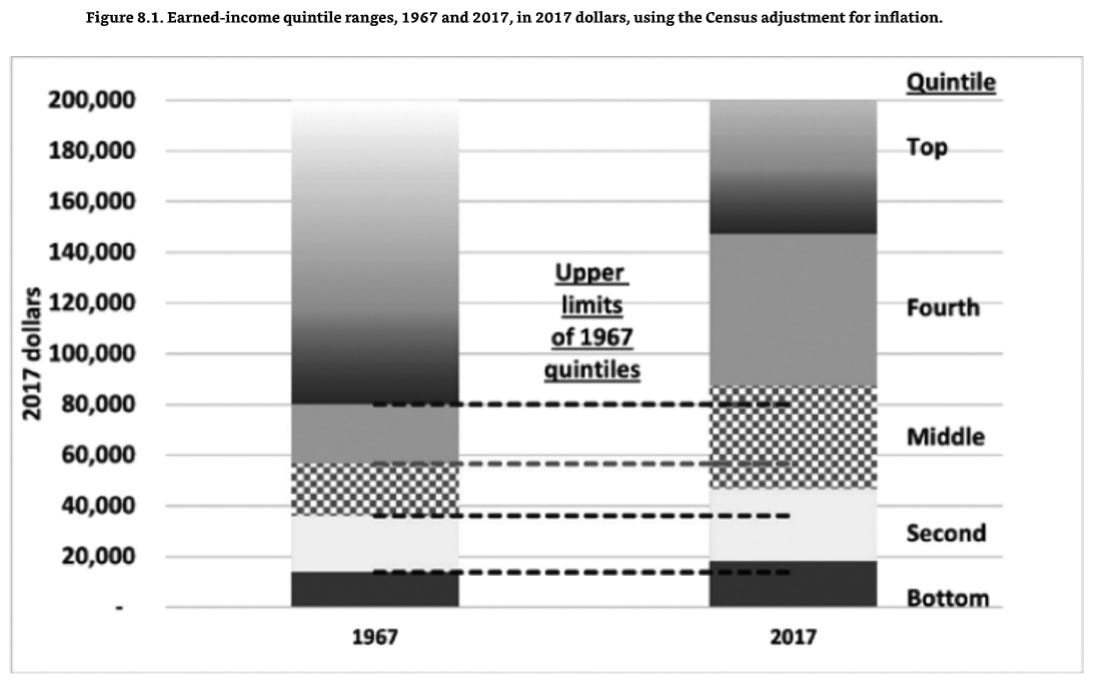

[T]his chart [Figure 8.1] shows that for 2017, in addition to the top quintile, the entire fourth quintile and about 18 percent of the middle quintile all earned real incomes that would have been in the top quintile 50 years earlier in 1967. This means that 44 percent of all households in 2017 had incomes that were earned only by the top quintile fifty years before. In 2017, 58 percent of the middle quintile had earnings that were in the fourth quintile in 1967. More than a third of second-quintile households in 2017 earned what middle-quintile households earned in 1967. Although 77 percent of the bottom quintile in 2017 still earned at the bottom-quintile rate for 1967, that still means that 23 percent of those formerly in the bottom quintile moved up to the second quintile, despite the fact that the proportion of prime work-age adults in the bottom quintile who chose not to work doubled between 1967 and 2017. That doubling of nonworking prime work-age adults accounts for most of those households that continued to be at the level of the 1967 bottom quintile.

With the exception of the prime work-age adults in the bottom quintile of earners who dropped out of the workforce, this is a story of extraordinary upward mobility driven by the efforts of American workers and the most prosperous economy in the history of the world … Absolute income mobility has produced rising real incomes for the vast majority of Americans over all extended periods of the nation’s history. Relative mobility measures how individuals’ incomes change compared to the income changes for others. Of course, as a relative measure, even people who benefit from significant increases in their earnings can fall to a lower rank, because other people increased their earnings by even more and moved ahead of them. For every person who rises in a relative measure like this, somebody else falls, even if both became substantially more prosperous.

As Angela Richidi has pointed out: “being poor year after year is uncommon in America, and a steady job almost always lifts households out of poverty. Persistent, or long-term poverty, is nearly nonexistent when someone in the household works steadily. This suggests that focusing exclusively on the ‘working poor’ as many politicians do, is misguided. Instead, policies aimed at getting more people to work consistently will better reduce poverty than perhaps anything else.”

As Michael Strain summarized economic mobility in America:

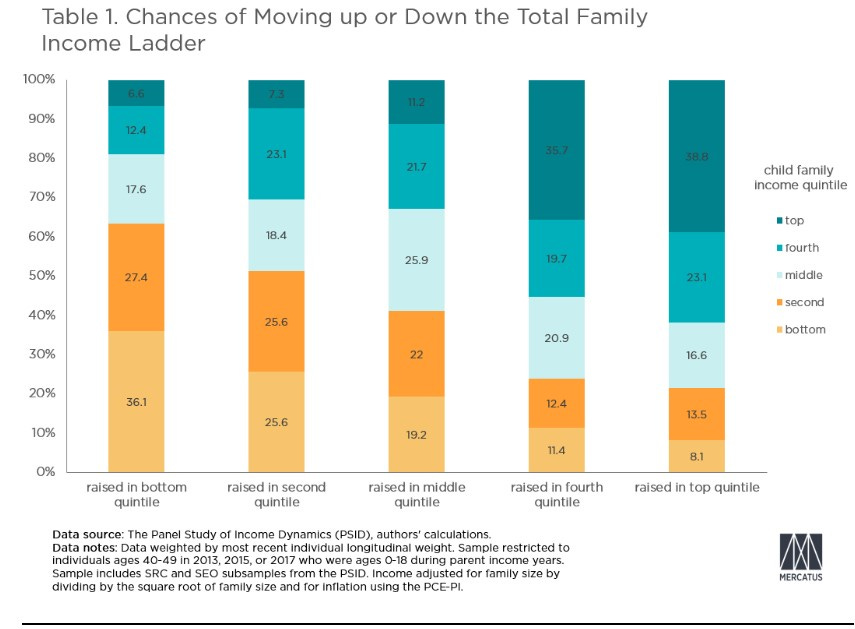

If you are born at the top, will you stay at the top as an adult? If you are born at the bottom, can you make it to the top when you become an adult? In other words: How “sticky” is income rank within the same family across generations? According to my data, about 36 percent of children raised in the bottom income quintile remain there as adults, and about 39 percent of children raised in the top quintile are themselves in the top quintile when they are in their 40s. What to make of these findings? On the one hand, arguing that one-third of children raised in the bottom remain there when they reach their prime earning years makes America seem like a rigid class society. On the other hand, arguing that two-thirds of children raised in the bottom escape that position as adults makes America seem quite upwardly mobile. The same issue presents itself with stickiness at the top. Of the children born into the top quintile, 39 percent stay there. That sounds sticky. But what if, instead, I characterized the data as saying that well over half of the children raised at the top do not remain at the top as adults?

Strain continues:

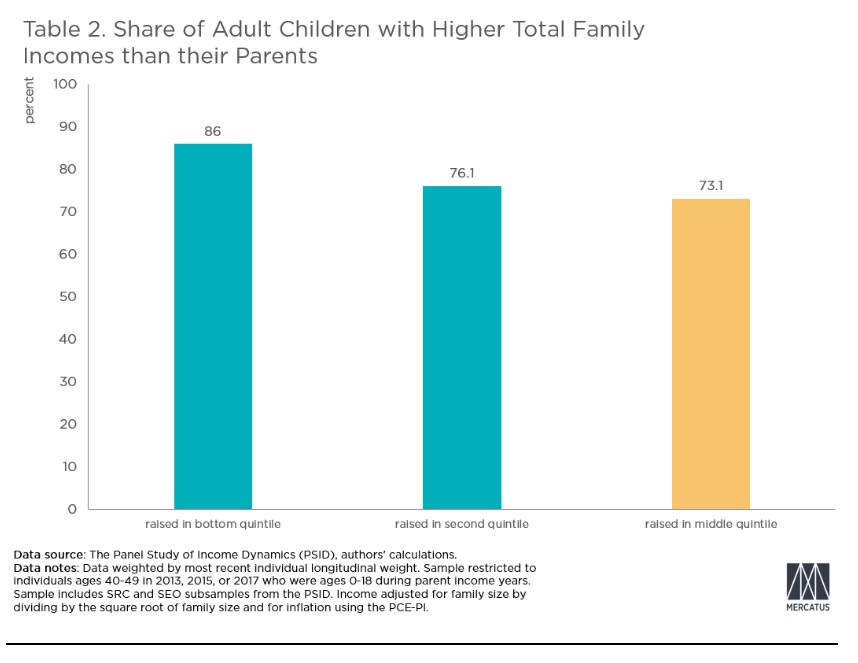

Using the same data and definitions as before, I computed absolute mobility statistics. As Chart 2 shows, I found that around 73 percent of Americans in their 40s have higher incomes than did their parents. Among children raised in the bottom quintile, 86 percent have gone on to enjoy higher incomes than their parents. In other words, 86 percent of today’s 40-somethings who were raised in the bottom quintile have higher incomes than their parents did when the parents were in their 40s. This is particularly important since upward mobility from the bottom of the income distribution is what we should care about most.

As the authors of The Myth of American Inequality point out, while disparities in economic measures remain across races, their magnitude drops substantially when more reasonably measured, and remaining disparities are largely influenced by rates of workforce participation:

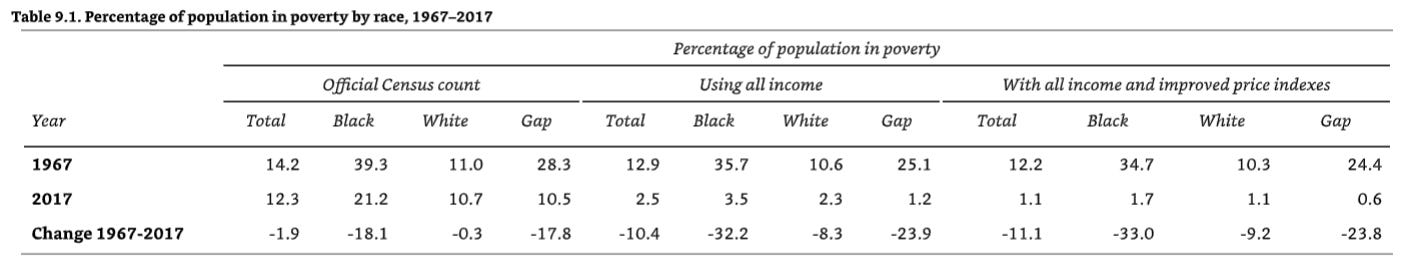

Counting all of the $1.9 trillion in transfer payments that have been omitted by Census dramatically reduces the poverty rate. Table 9.1 shows a comparison of the official poverty rates from the Census Bureau with rates using a complete accounting of all earning and transfer payments. The Black poverty rate falls to 3.5 percent, and the White poverty rate falls to 2.3 percent in 2017, leaving a gap of only 1.2 percent. Using more accurate price indexes as described in Chapter 6 to calculate poverty thresholds causes the Black and White household poverty rates to fall to only 1.7 percent and 1.1 percent, respectively, in 2017, virtually eliminating the gap in poverty based on race. Getting the data right makes a big difference.

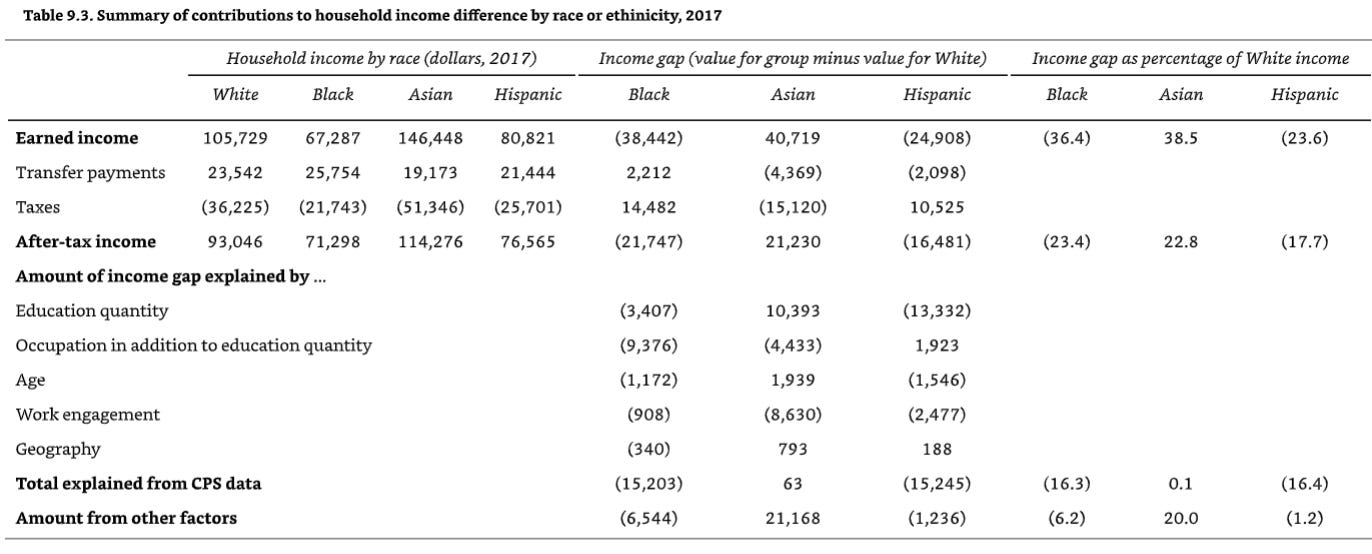

The poverty rate for Hispanics drops from 18.3 percent to only 1.7 percent, cutting the gap with the White rate from 7.6 percentage points to 0.6 percentage points. The proportion of prime work-age adults who were employed declined by more than 40 percent between 1967 and 2017 for both Black and White prime work-age adults in the bottom quintile and by about one-tenth that much for those in the second quintile. The proportion of White prime work-age adults working increased slightly in the middle and higher quintiles, while the proportion for Blacks decreased slightly. Although the decline in the number of prime work-age persons who were employed was the largest single cause of the overall earned-income disparity between the bottom quintile and other quintiles for the total population … Differences in occupational choices within an educational level, whether the reflection of personal preferences, differences in the quality of elementary and secondary education, or other factors, accounted for about 24 percent of the earned-income gap between Black and White adults … Age and geography also have contributed to the observed differences in earned income by race and ethnicity. In the Black population, individuals under the age of thirty-six constituted a 20 percent larger proportion of the prime work-age adults than in the White population. As a result, on average, White prime working-age adults in 2017 had 2.6 more years of job experience than the average Black adult. This added experience accounts for about 3 percent of the earned-income gap between the two races … Hispanic workers were even younger with more limited experience, which contributed about 6 percent to their earned-income gap with Whites … On average, Black households received $2,212 more in transfer payments than White households, and White households paid $14,482 more in taxes than Black households. As a result, the overall gap between Black and White household incomes after transfers and taxes was more than one-third smaller than the gap for earned income (23.4 percent versus 36.4 percent) … Table 9.3 also summarizes the contributions of factors identified in this chapter that explain some of the differences in household earned income among racial and ethnic groups using data in the Current Population Survey—the quantity of education received, occupational choices within an educational level, age, the choice of whether to work, and geographic location. These five factors are listed in the table along with their contributions to the income gap for each of the groups. In sum, these five factors account for more than two-thirds of the gap in income after transfers and taxes between Black and White households. They account for more than 90 percent of the gap between Hispanic and White households.

Negative gaps mean that the group being compared has lower average income than White households. Positive gaps mean it has higher income. The amount of income gap explained by each of the factors can be either negative or positive as well. A negative effect means that the listed factor caused the income of the group being compared to be lower relative to White households than it otherwise would have been. For example, education quantity caused Hispanic households’ income to be $13,332 lower than it would have been if Hispanic households had the same educational level as White households.

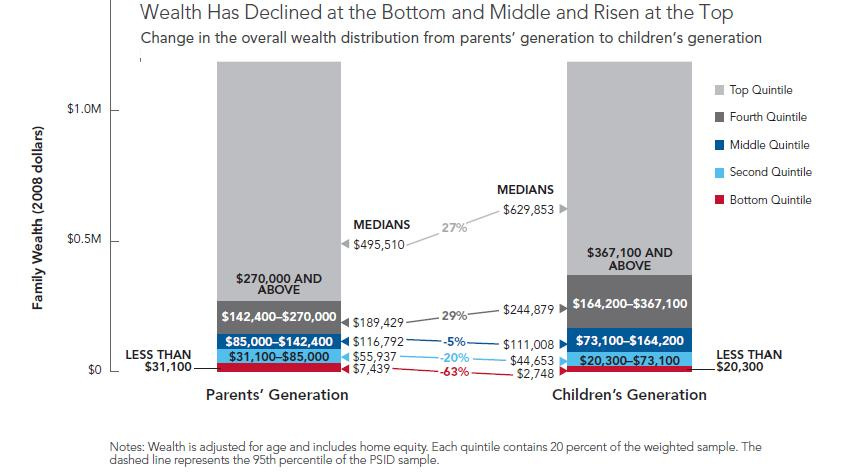

Researchers have found that intergenerational mobility declined sharply for cohorts born between 1942 and 1953 compared to those born between 1957 and 1964, and that the share of children whose income exceeds that of their parents fell by about 3 percentage points. Despite large increases in anti-poverty programs, people born into poor or middle income families have grown up in families with less wealth today, not more, perhaps because an increased reliance on government benefits programs has reduced the sort of home and business ownership that tends to increase wealth.

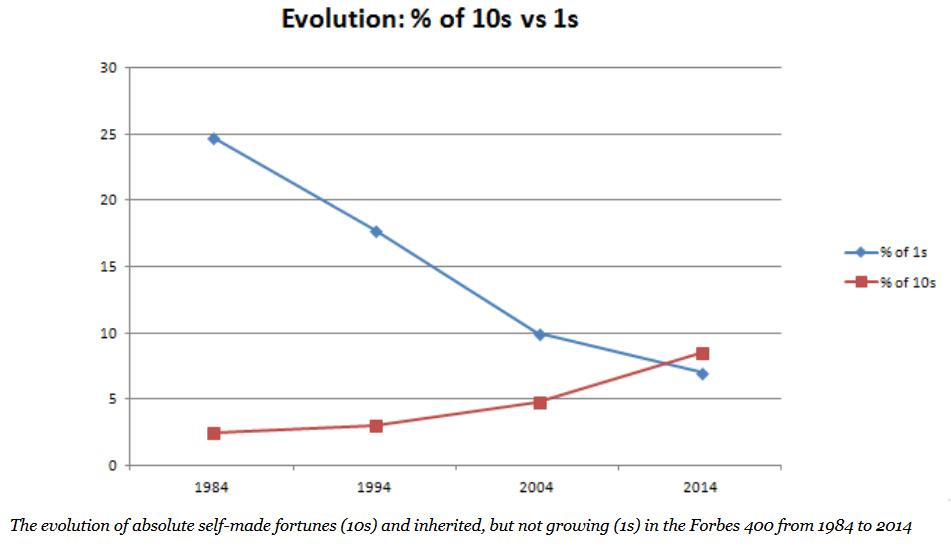

Over time, more and more of the wealth of the Fortune 400’s wealthiest people was self-made, rather than inherited. (The chart below shows the changes in how the Forbes 400 fortunes were made over the past three decades. The magazine gives each member a score on a scale from 1 (blue) to 10 (red), with “a 1 indicating the fortune was completely inherited, while a 10 was for a Horatio Alger-esque journey.”)

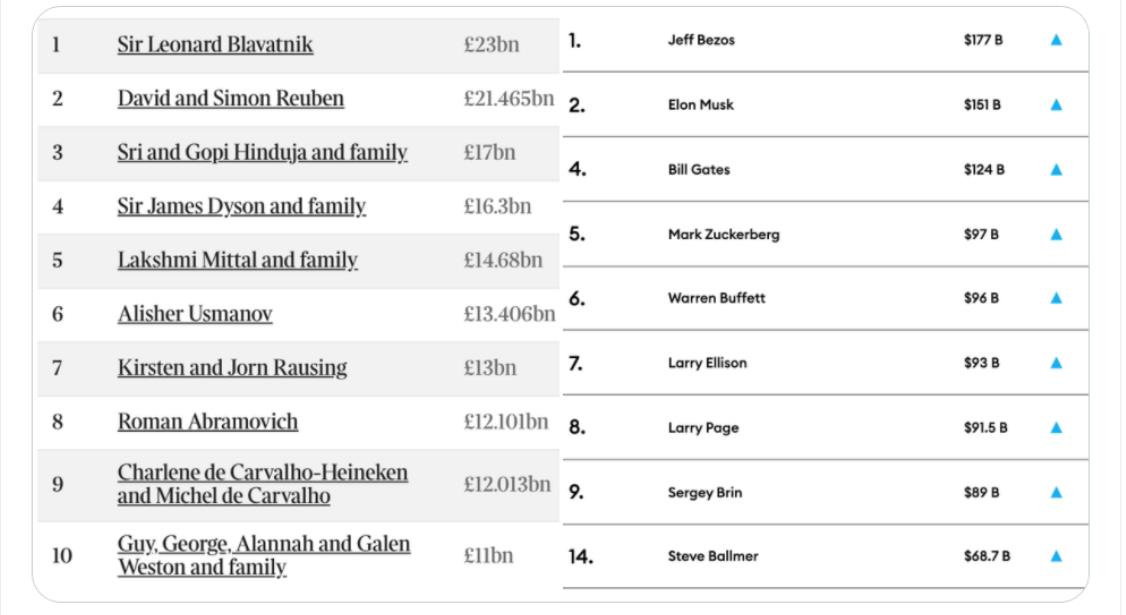

Reported in May, 2021, the 10 richest U.S. billionaires are almost all self-made tech entrepreneurs. The 10 billionaires in the United Kingdom are mostly oligarchs, property magnates and dynastic heirs.

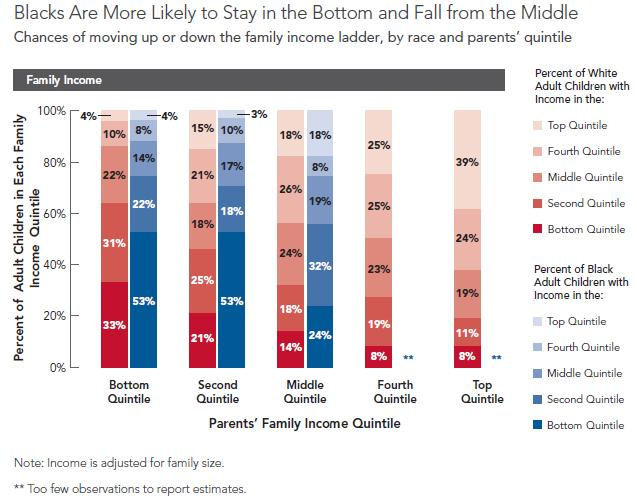

And despite the civil rights movement, and large increases in anti-poverty programs, the majority of black families have fallen into lower income quintiles than their parents’ families, such that 53 percent of blacks raised in a family in the second quintile of income have fallen to the bottom quintile, and 56 percent of blacks raised in a family in the middle quintile of income have fallen to the second or bottom quintiles.

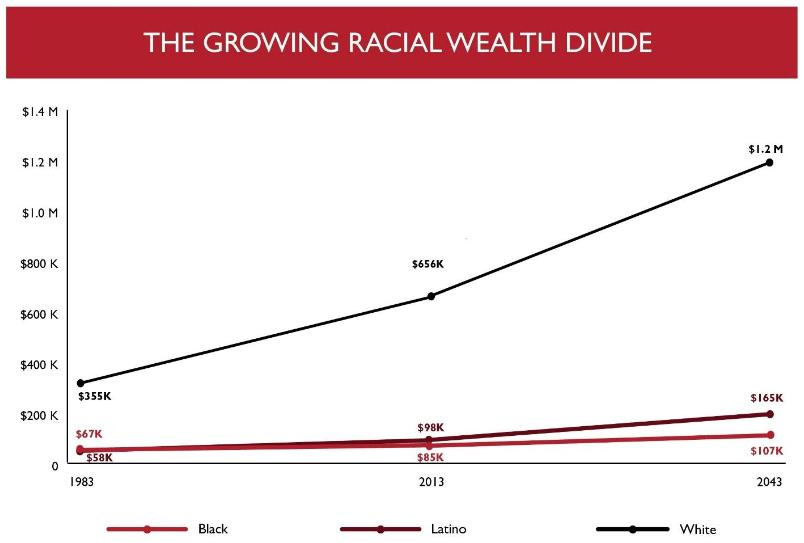

If current policies remain in place, we can expect the wealth divide between whites and other minorities to grow larger in time.

Incidentally, these disparities in the provision of federal welfare benefits raise uncomfortable questions about how they might interact with policies based on the false assumption that disparities in various outcomes are caused by racism, and not other things. As Matt Weidinger of the American Enterprise Institute writes:

[T]he new order [the White House Executive Order on “Further Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government”] leaves out a fundamental question. When it comes to welfare programs, what exactly does equity mean? For example, what will the Department of Agriculture’s new equity team make of the fact that non-Hispanic whites constituted 38.4 percent of all food stamp recipients in mid-2020, below that group’s share of the US population in poverty (42.8 percent) then? Or that 2.4 percent of food stamps recipients were Asian Americans, similarly below that group’s share of the US population in poverty (4.4 percent) that year? Would a more equitable social safety net provide more benefits to those groups—despite their having the lowest overall poverty rates of any racial or ethnic categories? Similarly, what will the Social Security Administration’s equity team make of the fact that two thirds of children receiving Supplemental Security Income benefits are boys? Would equity require equal numbers of girls to qualify? Once equity teams sort out who is being “disfavored,” they will have to determine what their vision of equity in benefit programs actually looks like. Would it require adding new recipients or removing current ones until their desired balance of “actual or perceived race, color, ethnicity, sex” and so on is achieved? The Executive Order doesn’t say, but unsurprisingly suggests that more benefit provision is the goal: agency equity action plans “shall include” a review of “potential barriers that underserved communities may face in accessing and benefitting from the agency’s policies, programs, and activities” along with “strategies, including new or revised policies and programs, to address the barriers.” Predictably, no mention is given to how much all this will cost taxpayers of all backgrounds.

As the famed French observer of American culture. Alexis de Tocqueville, wrote back in 1840, commenting on how the growth in government regulation threatened to result in trained helplessness:

Above this race of men stands an immense and tutelary power, which takes upon itself alone to secure their gratifications and to watch over their fate. That power is absolute, minute, regular, provident, and mild. It would be like the authority of a parent if, like that authority, its object was to prepare men for manhood; but it seeks, on the contrary, to keep them in perpetual childhood … For their happiness such a government willingly labors, but it chooses to be the sole agent and the only arbiter of that happiness; it provides for their security, foresees and supplies their necessities, facilitates their pleasures, manages their principal concerns, directs their industry, regulates the descent of property, and subdivides their inheritances: what remains, but to spare them all the care of thinking and all the trouble of living? Thus it every day renders the exercise of the free agency of man less useful and less frequent; it circumscribes the will within a narrower range and gradually robs a man of all the uses of himself. The principle of equality has prepared men for these things; it has predisposed men to endure them and often to look on them as benefits. After having thus successively taken each member of the community in its powerful grasp and fashioned him at will, the supreme power then extends its arm over the whole community. It covers the surface of society with a network of small complicated rules, minute and uniform, through which the most original minds and the most energetic characters cannot penetrate, to rise above the crowd. The will of man is not shattered, but softened, bent, and guided; men are seldom forced by it to act, but they are constantly restrained from acting. Such a power does not destroy, but it prevents existence; it does not tyrannize, but it compresses, enervates, extinguishes, and stupefies a people, till each nation is reduced to nothing better than a flock of timid and industrious animals, of which the government is the shepherd.

The incentive structures created by this dynamic operate on human being and their own human nature in ways that transcend race and other immutable traits. As Martin Luther King, Jr., observed, the key is to apply those rules that liberate the potential of all people to all people, regardless of race or other immutable traits: “When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” The psychological value of earned success has been notably described by Frederick Douglass, having escaped slavery. As described in Timothy Sandefur’s “Frederick Douglass: Self-Made Man”:

Knowing he could reap the rewards of his own toil “placed me in a state of independence,” [Douglass] wrote, and his first day of freely chosen labor seemed to him “the real starting point of something like a new existence … The fifth day after my arrival I put on the clothes of a common laborer, and went upon the wharves in search of work. On my way down Union street I saw a large pile of coal in front of the house of Rev. Ephraim Peabody, the Unitarian minister. I went to the kitchen-door and asked the privilege of bringing in and putting away this coal. ‘What will you charge?’ said the lady. ‘I will leave that to you, madam.’ ‘You may put it away,’ she said. I was not long in accomplishing the job, when the dear lady put into my hand two silver half-dollars. To understand the emotion which swelled my heart as I clasped this money, realizing that I had no master who could take it from me -- that it was mine -- that my hands were my own, and could earn more of the precious coin … I was not only a freeman but a free-working man, and no master Hugh stood ready at the end of the week to seize my hard earnings.’ … Thus, Douglass viewed economic freedom as more than an incentive: it was the source and symbol of personal liberation. He made this idea explicit in a later speech: “What is freedom? It is the right to choose one’s own employment.”

Frederick Douglass also said in a speech in 1865, “Everybody has asked the question, and they learned to ask it early of the abolitionists, ‘What shall we do with the Negro?’ I have had but one answer from the beginning. Do nothing with us! Your doing with us has already played the mischief with us. Do nothing with us! If the apples will not remain on the tree of their own strength, if they are wormeaten at the core, if they are early ripe and disposed to fall, let them fall! I am not for tying or fastening them on the tree in any way, except by nature’s plan, and if they will not stay there, let them fall. And if the Negro cannot stand on his own legs, let him fall also. All I ask is, give him a chance to stand on his own legs!” Douglass said of newly freed black slaves, “What they needed was more liberty to earn a living and keep the fruits of their labor, not paternalism, control, and oversight by a government dominated by whites.” Although Douglass rarely addressed socialism explicitly, in the words of his first biographer, Frederic May Holland, whose 1891 book was prepared with Douglass’s active involvement, “The present views of Mr. Douglass” were that while “our existing system of free labor in keen competition has many defects,” it had “succeeded much better than any other, not only in increasing the general wealth, to the benefit of even the poorest, but in developing individual energy, intelligence, industry, economy, foresight, perseverance, and self-control,” and that capitalism was simply “the only system of labor which a lover of liberty can favor consistently.” Douglass wrote that “My cause, first, midst, last, and always, was and is that of the black man; not because he is black, but because he is a man.” As Timothy Sandefur has written, “Pride in one’s own race was in his eyes no less ‘ridiculous’ than hatred of other races. The values he emphasized were good for the individual, and his hope was that Americans would learn to focus on the quality of each man and woman specifically, rather than on skin color, and thereby make racism obsolete … Douglass believed the nation’s heart was the principle of equality articulated in the Declaration of Independence, and that to assert the contrary was to concede the claims of white supremacists.”

In 1930, a group of Southern writers extolled the alleged virtues of the Old South, with its rejection of industrialization and commercialization, in a collection of essays entitled “I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition,” which stated in its introduction: “All the articles [herein] bear in the same sense upon the book's title-subject: all tend to support a Southern way of life against what may be called the American or prevailing way; and all as much as agree that the best terms in which to represent the distinction are contained in the phrase, Agrarian versus Industrial ... [A]n agrarian regime will be secured readily enough where the superfluous industries are not allowed to rise against it. The theory of agrarianism is that the culture of the soil is the best and most sensitive of vocations, and that therefore it should have the economic preference and enlist the maximum number of workers.” Contrary to this, Booker T. Washington, a former slave who became the first head of the Tuskegee Institute, embraced the Industrial Revolution and the Puritan work ethic, stating in an 1895 address to the International Exposition in Atlanta:

[T]he opportunity here afforded will awaken among us a new era of industrial progress. Ignorant and inexperienced, it is not strange that in the first years of our new life we began at the top instead of at the bottom; that a seat in Congress or the state legislature was more sought than real estate or industrial skill; that the political convention or stump speaking had more attractions than starting a daily farm or truck garden … To those of my race who depend on bettering their condition in a foreign land or who underestimate the importance of cultivating friendly relations with the Southern white man, who is their next door neighbor, I would say: “Cast down your bucket where you are”-cast it down in making friends in every manly way of the people of all races by whom we are surrounded. Cast it down in agriculture, mechanics, in commerce, in domestic service, and in the professions. And in this connection it is well to bear in mind that whatever other sins the South may be called to bear, when it comes to business, pure and simple, it is in the South that the Negro is given a man’s chance in the commercial world, and in nothing is this Exposition more eloquent than in emphasizing this chance. Our greatest danger is that in the great leap from slavery to freedom we may overlook the fact that the masses of us are to live by the productions of our hands, and fail to keep in mind that we shall prosper in proportion as we learn to dignify and glorify common labour, and put brains and skill into the common occupations of life; shall prosper in proportion as we learn to draw the line between the superficial and the substantial, the ornamental gewgaws of life and the useful. No race can prosper till it learns that there is as much dignity in tilling a field as in writing a poem. It is at the bottom of life we must begin, and not at the top. Nor should we permit our grievances to overshadow our opportunities … There is no defense or security for any of us except in the highest intelligence and development of all. If anywhere there are efforts tending to curtail the fullest growth of the Negro, let these efforts be turned into stimulating, encouraging. and making him the most useful and intelligent citizen. Effort or means so invested will pay a thousand per cent interest. These efforts will be twice blessed--”blessing him that gives and him that takes.” … Nearly sixteen millions of hands will aid you in pulling the load upward. or they will pull against you the load downward. We shall constitute one-third and more of the ignorance and crime of the South, or one-third its intelligence and progress; we shall contribute one-third to the business and industrial prosperity of the South, or we shall prove a veritable body of death. stagnating, depressing, retarding every effort to advance the body politic.

Booker T. Washington also explained that the best way to dispel self-doubt as a minority is through objective performance:

In the next essay in this series, we’ll continue to look at income mobility in relation to race.