Merit and Society – Part 2

When political ideology trumps merit.

Continuing this essay series on the role of merit in society, this essay will explore some past and present examples in which political ideology has come to trump merit.

As explored in a previous essay series, today, various so-called “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion” (DEI) programs are stifling scientific innovation by focusing hiring principles on race-based ideology instead of scientific merit. As a variety of scientists (including two Nobel laureates) write in their paper “In Defense of Merit in Science,” this modern movement against scientific merit recalls the experience of scientists in the old Soviet Union:

History demonstrates the dangers of replacing merit-based science with ideological control and social engineering. In the Soviet Union (USSR), the aberrations of Trofim Lysenko had catastrophic consequences for science and society. An agronomist and “people’s scientist” who came from the “superior” class of poor peasants, Lysenko rejected Mendelian genetics because of its supposed inconsistency with Marxist ideology. Dissent from Lysenko’s ideas was outlawed and his opponents were fired or prosecuted. Lysenko’s ideologically infused agricultural ideas were put into practice in the USSR and China, where, in both countries, they led to decreased crop yields and famine. Today, biology is again being subjugated to ideology -- medical schools deny the biological basis of sex, biology courses avoid teaching the heritability of traits, and so on. More examples of ideological subversion of science, relevant to physics and chemistry, were discussed in a recent viewpoint.

The “viewpoint” mentioned above is a letter by Anna I. Krylov that appeared in the Journal of Chemistry Letters in which she writes:

I came of age during a relatively mellow period of the Soviet rule, post-Stalin. Still, the ideology permeated all aspects of life, and survival required strict adherence to the party line and enthusiastic displays of ideologically proper behavior. Not joining a young communist organization (Komsomol) would be career suicide -- nonmembers were barred from higher education. Openly practicing religion could lead to more grim consequences, up to imprisonment. So could reading the wrong book (Orwell, Solzhenitsyn, etc.). Even a poetry book that was not on the state-approved list could get one in trouble. Science was not spared from this strict ideological control. Western influences were considered to be dangerous. Textbooks and scientific papers tirelessly emphasized the priority and pre-eminence of Russian and Soviet science. Entire disciplines were declared ideologically impure, reactionary, and hostile to the cause of working-class dominance and the World Revolution. Notable examples of “bourgeois pseudoscience” included genetics and cybernetics. Quantum mechanics and general relativity were also criticized for insufficient alignment with dialectic materialism. Most relevant to chemistry was the antiresonance campaign (1949−1951). The theory of resonating structures, which brought Linus Pauling the Nobel prize in 1954, was deemed to be bourgeois pseudoscience. Scientists who attempted to defend the merits of the theory and its utility for understanding chemical structures were accused of “cosmopolitism” (Western sympathy) and servility to Western bourgeois science. Some lost jobs. Two high-profile supporters of resonance theory, Syrkin and Dyatkina, were eventually forced to confess their ideological sins and to publicly denounce resonance. Meanwhile, other members of the community took this political purge as an opportunity to advance at the expense of others.8 As noted by many scholars, including Pauling himself, the grassroots antiresonance campaign was driven by people who were “displeased with the alignment of forces in their science”. This is a recurring motif in all political campaigns within science in Soviet Russia, Nazi Germany, and McCarthy’s America -- those who are “on the right side” of the issue can jump a few rungs and take the place of those who were canceled.

That tragic history bears important lessons for today. As the scientist authors of “In Defense of Merit in Science” write:

To ensure that the best scientific ideas are put forth, merit must also be applied to evaluate research proposals and prospective students and faculty. Here, merit comprises the scientific claims contained in the research plans, the quality of the proposed methods, and the expertise and academic track records of the individuals involved. Scientific truths are universal and independent of the personal attributes of the scientist. Science knows no ethnicity, gender, or religion. Of course, by itself, universalism does not prevent the personal views of scientists, which are influenced by culture and society, from affecting the practice of science. Indeed, scientists have not always lived up to the ideals of fairness and impartiality in evaluating merit. In the past, scientific culture contributed to the exclusion of various groups from the scientific enterprise. For example, sexism limited women’s entry into science, and those who helped raise awareness of such issues have done science a service. However, the shortcomings of individuals or the community should not be confused with the science itself. Whether sexism prevented Cecilia Payne Gaposchkin from receiving credit for her conclusion that the Sun was made mostly of hydrogen is irrelevant to the fact that the Sun is made mostly of hydrogen. Although there are feminist critiques of how glaciologists have conducted themselves, there is no such thing as “feminist glaciology,” just as there is no “queer chemistry,” “Jewish physics,” “white mathematics,” “indigenous science,” or “feminist astronomy.” Glacial, physical, genetic, or prehistoric phenomena are independent of the positionality of the scientist. By prioritizing the truth value of scientific research, personal influences of individual scientists are minimized. Merit-based science is truly fair and inclusive. It provides a ladder of opportunity and a fair chance of success for those possessing the necessary skills or talents. Neither socioeconomic privilege nor elite education is necessary.

As mentioned in the previous essay, objective standardized tests have allowed intellectually talented people from lower-status classes and racial and ethnic minorities to become noticed and advance, going back to China nearly two thousand years ago. The authors of “In Defense of Merit in Science” also write that:

Merit is a vehicle for upward mobility. Recruiting, developing, and promoting individuals based on their talent, skills, and achievements has enabled many who started life in disadvantaged conditions to realize their dreams and build better lives. Imperfections in a merit-based system are not grounds for dismantling or disrupting it. Changes to an effective system should occur only when the superiority of the alternative has been demonstrated. There is no evidence that CSJ [Critical Social Justice] produces better mathematics, physics, or chemistry, and it has already damaged medicine and psychiatry.

Indeed, the authors cite just some examples of how “social justice” theories are hurting scientific progress. They write:

The worst excesses of CSJ ideology are spreading to medicine, psychology, and global public health with worldwide implications. For example, in global public health, the ideology manifests in the Decolonize Global Health movement, which calls for dismantling global health, questions research-based knowledge, emphasizes intergroup and international antagonisms, and challenges universalism as an ideal for global health, humanitarian aid, and development assistance. As an illustration, The Lancet published a paper in 2020 titled “Adopting an Intersectionality Framework to Address Power and Equity in Medicine” -- a call to adopt CSJ ideology in medical education and practice. This is reminiscent of the ideological control of science and medicine in the USSR. In medicine, Marxist ideology manifested itself in “‘workerizing’ … [the] apparatus [of medical care]” (i.e., selecting future doctors from the working class, rather than the intelligentsia by means of class-based quotas) and prioritizing medical care for citizens based on class (the proletariat was to be given higher priority than the farm workers; the farm workers, higher priority than the intelligentsia; and so on). However, in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics), where education provides objectively assessable technical skills, attendance at a top university provides little advantage in students’ earnings potential. Measured 10 years postgraduation, a top-tier education provided no significant earnings advantage for science majors and at best a marginally significant one for engineering majors.

To that last point, economists studying the issue found the following:

Most studies examine college major and college selectivity separately, but we are interested in how the combination of college major and college selectivity are correlated with earnings. Why should the interaction of college selectivity and college major matter? With all the attention paid to the earnings premium associated with attendance at the most selective colleges, students who cannot afford to attend the most prestigious colleges and those who are unable to gain admittance may perceive themselves to be at a sizeable disadvantage in the labor market after graduation. However, just because average earnings across all students at more selective colleges are higher, it does not mean the average within all majors is higher. To help motivate this issue, consider a student who wants to be an engineer. The question of interest is, does it matter, in terms of say future earnings, whether the engineering student attends a top ranked college or a less selective college, or is it simply being an engineer that matters? If, on average, engineers from middle or bottom ranked colleges earn about the same as engineers from top ranked colleges, then the student may be better off choosing to attend the less selective, and less expensive, college. Graduates with more technical majors of business, engineering, and science have the highest earnings in each college selectivity type … These simple descriptive statistics suggest considerable variation in earnings according to both college selectivity and college major. That is, what you study may be as important as where you go. The statistically weakest earnings differences for a given major across college selectivity types is found for science majors where there are no statistically significant differences between any of the college selectivity groups. A somewhat similar pattern holds for engineering majors when comparing top selectivity to the other groups. There is only a marginally significant earnings difference between engineering graduates from top and middle selectivity colleges, but no significant difference between engineering majors from top and bottom selectivity colleges. Considering that the broad categories of science and engineering encompass all of the STEM fields, these results suggest that in these more technical fields it may be that the skills a student acquires in these fields are more important than the institution attended. For social science and education majors, there is a premium to attending a top selectivity college over either a middle or bottom selectivity college, with the top-bottom difference greater than the top-middle difference. However, there is no statistically significant difference between middle and bottom selectivity colleges in these fields. For humanities, there is a sizeable premium to attending a top over a bottom selectivity college, but not to attending a top over a middle selectivity college.

The authors of “In Defense of Merit in Science” go on to analyze modern “recurring themes in these papers: … science is racist; and … merit-based policies should be replaced by identity-based policies”:

The American Chemical Society published an editorial signed by all senior editors alleging the existence of systemic racism in chemistry publishing. Among several action points, they pledged to include “diversity of journal contributors as an explicit measurement of Editor-in-Chief performance.” A Nature editorial in 2021 reaffirms this narrative: … “too often, conventional metrics -- citations, publication, profits -- reward those in positions of power, rather than helping to shift the balance of power.” Scientific positions, grants, and article acceptances should be awarded on the basis of their quality rather than treated as commodities to be distributed based on identity categories. The telos of science is the search for provisional truth and the production of knowledge, not the redistribution of rewards to achieve activists’ visions of equity or reparative justice. The American Psychological Association makes a lengthy apology to people of color for the association’s supposed role in “promoting, perpetuating, and failing to challenge racism, racial discrimination and human hierarchy in the U.S.” They promote a radical, nonevidence-based, untested psychotherapy that encourages patients to see their problems through a lens of power and race, a recommendation flagrantly abandoning known best practices, such as centering therapy on the concerns of the patient, rather than those of the therapist, and cognitive behavioral therapy. This is not science; it is ideology and, arguably, malpractice … Many scientific societies now encourage or require identity-based quotas for speakers and award recipients. NAS [the National Academy of Sciences] now penalizes its nominating committees if their nominations are insufficiently diverse. If one has any doubt that CSJ ideology is replacing merit-based science, this quote from McNutt (president of the NAS) and Castillo-Page (its Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer) is the smoking gun: “Not so long ago, the NAS might have naively argued that its membership could not reflect the diversity of the American public it serves until universities fixed the ‘leaky pipeline’ of too many women opting out of careers in scientific research almost before they begin, or until elementary and secondary schools started motivating more students of color to study STEMM disciplines and prepared them for success in college and beyond. But in 2021, it is simply not acceptable to wait for ‘bottom-up’ solutions.” This implies that membership in the Academy should reflect an aspirational dream of proportional representation, rather than the real demographics of the most meritorious scientists. The secretary of the NAS revealed how this will operate: “We assign slots [to different fields] based on the diversity of the lists of nominees that get forwarded” and “If they used [their slots] to pick a bunch of white guys from Harvard, they get penalized.” In some ways, this is trivial concerning the production of science. Membership in NAS is not science; it is an honor in recognition of contributions to science. In that sense, it is a reward to be distributed, not a scientific discovery or invention of any import. But if we continue to subjugate meritocracy to CSJ by failing to reward the best-performing individuals and recognize the most creative and influential work, we risk eroding scientific excellence. When NAS signals “this is the way we provide scientific rewards,” other scientific institutions will follow their lead. Race and gender-based selection for honors, conference presentations, and awards undermines the achievements of individuals from underrepresented groups by creating an impression that women and minorities cannot compete in an open marketplace of ideas and talent. It is also offensive to know that one's research was selected, not strictly for its merit, but at least partly due to one's ethnicity or gender. This is “the soft bigotry of low expectations” -- the creation of different standards based on the perceived or real historical oppression of some individuals. Some journal editorials have begun urging authors to preferentially cite “articles led by colleagues from different gender identities and geographical areas,” in the spirit of “citation justice.” Tools to implement “citation justice” already exist. The publisher Elsevier encourages authors to apply “citation justice” on a voluntary basis, while other publishers have implemented policies, such as mandatory DEI statements, to that end. The promoters of “citation justice” justify the practice by the assumption that differences in citation rates are due to racist or sexist biases in publishing. This, however, is an unsubstantiated claim … In hiring at many universities, faculty applicants are now required to write DEI statements. In recent faculty searches in the life sciences at UC Berkeley, threequarters of the candidates were eliminated solely on the basis on their DEI statements. Putting aside separate objections that the use of DEI statements to screen applicants constitutes a political litmus test and a form of (possibly illegal) compelled speech, by reducing the viable applicant pool, it likely undermines the quality of science. Thus, a brilliant mathematician (or physicist or cognitive scientist) may be filtered out by virtue of having expressed insufficient enthusiasm or familiarity with the particular version of DEI that the institution supports. DEI statements are often expected to embrace CSJ; statements that express support for the ideals of liberal social justice, such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream of a colorblind society, are rejected. As UC Berkeley’s sample rubric for evaluating diversity statements states, candidates who intend to treat “all students the same regardless of their background” will be given the lowest score. Admittedly, meritocracy is imperfect. The best and brightest do not always win. But the idea that meritocracy is nothing but a myth is demonstrably false, indeed absurd. Were it but a myth, college admissions and hiring could be conducted without regard to applicants’ qualifications, and students or employees could be selected at random.

The authors go on to elaborate on the need for merit-based science, and ways to restore its primacy:

The primacy of merit-based scientific truth claims raises the following question: How can we apply merit consistently and effectively? … Yet there are established good practices that have been honed and refined over decades. How, then, can the potential for bias be mitigated so that even subjective judgments have a laser-like focus on merit? We suggest that two questions are central to the evaluation of scientific merit (see Figure 2): (1) How important is the finding? (2) How strongly does the evidence presented indicate that the main claims are true?

Differences of opinion may exist regarding both of these dimensions. However, the key is that focusing on the importance of the finding and the strength of evidence can limit bias. Astronomers may value the discovery of a new exoplanet more than material scientists value improvements in ceramic tensile strength, but this is normal science and can be threshed out among scientists. The identity or positionality of the authors is irrelevant … There is a large literature in the field of psychology on the role that demographic biases play in how we judge individuals. Such biases are real and a justified concern, but fighting them with opposite biases and undermining merit is counterproductive. Two of the most robust findings in the literature are: (1) people massively judge others on their merits when their merits are clear and salient; and (2) in such situations, stereotypes and implicit biases are minimized. Thus, a sharp focus on merit minimizes bias and maximizes the chances that those who best meet the relevant standards (for admissions, hiring, publication, or anything else) will be rewarded, thereby promoting inclusion. For example, standardized tests can help to fairly evaluate applicants from diverse backgrounds and -- if used properly -- increase diversity. A strict focus on merit, properly implemented, also reduces the influence of bias, department politics, nepotism, and favoritism, thus facilitating diversity, while maximizing scientific quality and the public’s confidence and trust in the academy and science. How do we begin the process of depoliticizing science and strengthening merit-based practices? We offer six concrete suggestions:

Insist that government funding for research be distributed solely on the basis of merit.

Ensure that academic departments and conferences select speakers based on scientific, rather than ideological, considerations.

Ensure that admissions, hiring, and promotion are meritbased and free from ideological tests.

Publish and retract scientific papers on the basis of scientific, not ideological, arguments or due to public pressure.

Require that universities enforce policies protecting academic freedom and freedom of expression, according to best practices promulgated by nonpartisan free speech and academic freedom organizations, such as the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression.

Insist that university departments and professional societies refrain from issuing statements on social and political issues not relevant to their functioning, as recommended in the University of Chicago’s Kalven Report.

As we were finalizing the manuscript for publication, the Office of Science and Technology Policy of the White House released a 14-page long vision statement outlining the priorities for the U.S. STEMM ecosystem. The word “merit” appears nowhere in the document. In February, 2023, The National Academy of Sciences released a report titled “Advancing Antiracism, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in STEMM Organizations: Beyond Broadening Participation.” The report describes merit as a nonobjective, “culturally construed” concept used to hide bias and perpetuate privilege, refers to objectivity and meritocracy in STEMM as myths, and calls for merit-based metrics of evaluation to be dismantled.

As Anna Krylov writes in the Journal of Chemistry Letters, the Soviet experience with ideologically-driven science has lessons for today:

Fast forward to 2021-- another century. The Cold War is a distant memory and the country shown on my birth certificate and school and university diplomas, the USSR, is no longer on the map. But I find myself experiencing its legacy some thousands of miles to the west, as if I am living in an Orwellian twilight zone. I witness ever-increasing attempts to subject science and education to ideological control and censorship. Just as in Soviet times, the censorship is being justified by the greater good. Whereas in 1950, the greater good was advancing the World Revolution (in the USSR; in the USA the greater good meant fighting Communism), in 2021 the greater good is “Social Justice” (the capitalization is important: “Social Justice” is a specific ideology, with goals that have little in common with what lower-case “social justice” means in plain English). As in the USSR, the censorship is enthusiastically imposed also from the bottom, by members of the scientific community, whose motives vary from naive idealism to cynical power-grabbing. There is no doubt that many famous scientists had views or engaged in behaviors that, by today’s standards, are not acceptable. Their scientific legacies are often mixed; for example, Fritz Haber is both the father of modern chemical warfare and the man whose development of nitrogen fixation is feeding the planet. Scientists are not saints. They are human beings born into places and times they did not choose. Just as their fellow human beings do, each finds his or her way though the circumstances of their lives, such as totalitarian regimes, world wars, and revolutions. Sometimes they made the right choices, sometimes they erred. The lessons of history are numerous and unambiguous. Despite vast natural and human resources, the USSR lost the Cold War, crumbled, and collapsed. Interestingly, even the leaders of the most repressive regimes were able to understand, to some extent, the weakness of totalitarian science. For example, in the midst of the Great Terror, Kapitsa and Ioffe were able to convince Stalin about the importance of physics to military and technological advantage, to the extent that he reversed some arrests; for example, Fock and Landau were set free (however, an estimated ∼10% of physicists perished during this time). In the late forties, after nuclear physicists explained that without relativity theory there will be no nuclear bomb, Stalin rolled back the planned campaign against physics and instructed Beria to give physicists some space; this led to significant advances and accomplishments by Soviet scientists in several domains. However, neither Stalin nor the subsequent Soviet leaders were able to let go of the controls completely. Government control over science turned out to be a grand failure, and the attempts to patch the widening gap between the West and the East by espionage did not help. Today Russia is hopelessly behind the West, in both technology and quality of life. The book Totalitarian Science and Technology provides many more examples of such failed experiments.

Yet the Democratic Party in America has, as Ruy Texiera writes, “a merit problem”:

The Democrats have a merit problem. The traditional Democratic theory of the case ran like this: discrimination should be opposed and dismantled and resources provided to the disadvantaged so that everyone can fairly compete and achieve. Rewards -- job opportunities, promotions, commissions, appointments, publications, school slots, and much else -- would then be allocated on the basis of which person or persons deserved these rewards on the basis of merit. Those who were meritorious would be rewarded; those who weren’t would not be. But Democrats have lost interest in the last part of their case, which undermines their whole theory. Merit and objective measures of achievement are now viewed with suspicion as the outcomes of a hopelessly corrupt system, so rewards should instead be allocated on the basis of various criteria allegedly related to “social justice.” Instead of dismantling discrimination and providing assistance so that more people have the opportunity to acquire merit, the real solution is to worry less about merit and more about equal outcomes—“equity” in parlance of our times. Arguments can be made in defense of the anti-merit approach. You can’t swing a dead cat on most university campuses without hitting some academic who will give you 10,000 words on why this is actually a great idea. In my view, these arguments are universally specious but what shouldn’t be debatable is that ordinary people—ordinary voters—don’t buy the idea. They believe in the idea of merit and they believe in their ability to acquire merit and attendant rewards if given the opportunity to do so. To believe otherwise is insulting to them and contravenes their common sense about the central role of merit in fair decisions. As George Orwell put it: “One has to belong to the intelligentsia to believe things like that: no ordinary man could be such a fool.” Democrats are very shaky indeed on the idea of merit today but that wobbliness goes back quite a way to the origins of affirmative action as a tool for allocating jobs and school admissions. As it evolved in practice, affirmative action became bound up with preferences based on race (later also on gender) that were used to override allocations based on conventional measures of merit. While these practices have been with us for a long time, they have never been popular. Voters have been stubbornly resistant to the idea that it’s fair to allocate sought-over slots on the basis of race rather than merit … In typical polling from Pew in 2022, just 7 percent of the public thought high school grades should not be a factor in college admissions and a mere 14 percent thought standardized test scores should not be a factor. But an overwhelming 74 percent thought that race or ethnicity should not be a factor in college admissions. This pattern applied to all racial groups. Among blacks, 59 percent said race should not be a factor in college admissions compared to 11 percent who said high school grades should not be a factor and 21 percent who said the same about standardized tests. Hispanics and Asians were even more adamant in downgrading the use of race in admissions. The public’s view is perhaps best summed up in this time series question from Gallup: “Which comes closer to your view about evaluating students for admission into a college or university—applicants should be admitted solely on the basis of merit, even if that results in few minority students being admitted (or) an applicant’s racial and ethnic background should be considered to help promote diversity on college campuses, even if that means admitting some minority students who otherwise would not be admitted?” The most recent result is quite typical: 70 percent favored the merit-only approach and just 26 percent endorsed the need to admit less-qualified students on the basis of race. The public, whether Democrats are willing to admit it or not, are basically meritocrats when it comes to college admissions … None of this should come as a surprise to those who are attuned to real-world political trends, as opposed to media treatment of racial issues. In the very blue state of California in 2020, Democratic leaders put an initiative on the ballot, Proposition 16, that would have repealed the state’s ban on using affirmative action in school admissions and government contracting and employment decisions. The measure, endorsed by Governor Gavin Newsom and vice presidential candidate Kamala Harris, was widely seen as allowing schools to adjust merit-based admission policies to admit more blacks and Hispanics and fewer Asian-Americans in order to make black and Hispanic enrollment proportional to their share in the population. It was entirely consistent with Democrats’ increasing disenchantment with meritocratic criteria. But in spite of its prominent endorsements and generous funding, the measure failed by 57 to 43 percent, with working-class voters, Hispanics, Asians, whites, moderates and independents all in opposition. The people had spoken but Democrats were not inclined to listen. Instead, the last several years have seen an intensification of the drive to disregard meritocratic criteria in favor of identity-based characteristics. It has spread to countless workplaces and institutions and to an ever-wider variety of decisions within them. It is more or less the official orientation of the Biden administration. To insist on the centrality of merit, despite this being the dominant view among ordinary voters, is to invite accusations of racism in Democratic circles. And once merit is disregarded in one area, it becomes easy to disregard it in others. Most perniciously, it invades the realm of ideas. Where once it would have been unthinkable to screen candidates for faculty positions—in everything from economics to theoretical physics—on whether and how much they adhere to a particular ideological project on promoting “diversity,” it is now commonplace.

Texiera mentions the paper “In Defense of Merit in Science” discussed previously in astonishment:

Where once it would have been unthinkable to judge a scientific project or analysis on anything other than its intrinsic merits and truth value, that too is now commonplace. Indeed, a recent paper, “In Defense of Merit in Science” by 29 distinguished co-authors, including two Nobel laureates, literally could not get published by a mainstream journal because the paper was “hurtful” and because the concept of merit “has been widely and legitimately attacked as hollow”. It’s amazing that such a paper even needed to be written and truly shocking that it could not get published. But that is the reality of how far the downgrading of merit has spread in our society, with Democrats’ acquiescence. In fact, at the most fundamental level, it is now undermining the very basis of argumentation itself, which traditionally and correctly held that an argument was to be adjudicated on the basis of merit -- the logic and evidence behind it -- rather than the identity or political agenda of the person making the argument.

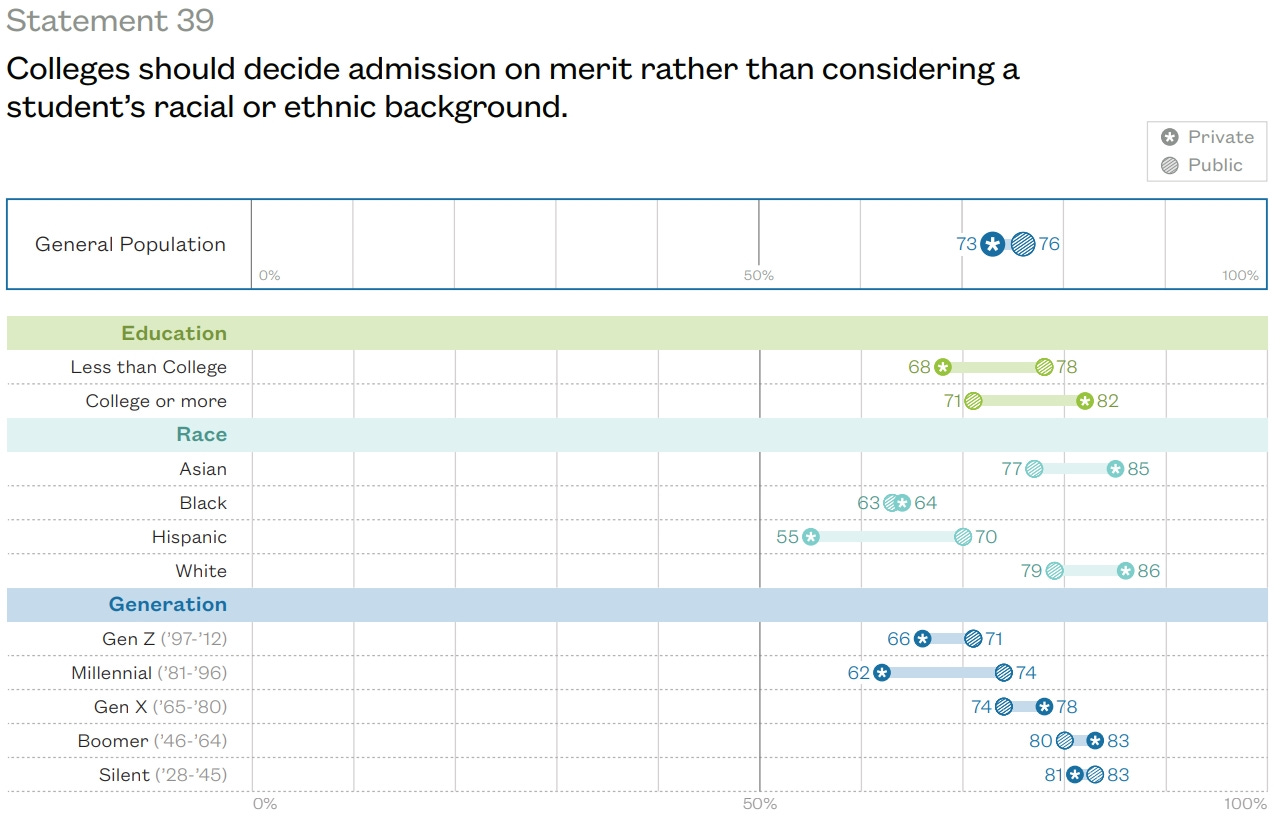

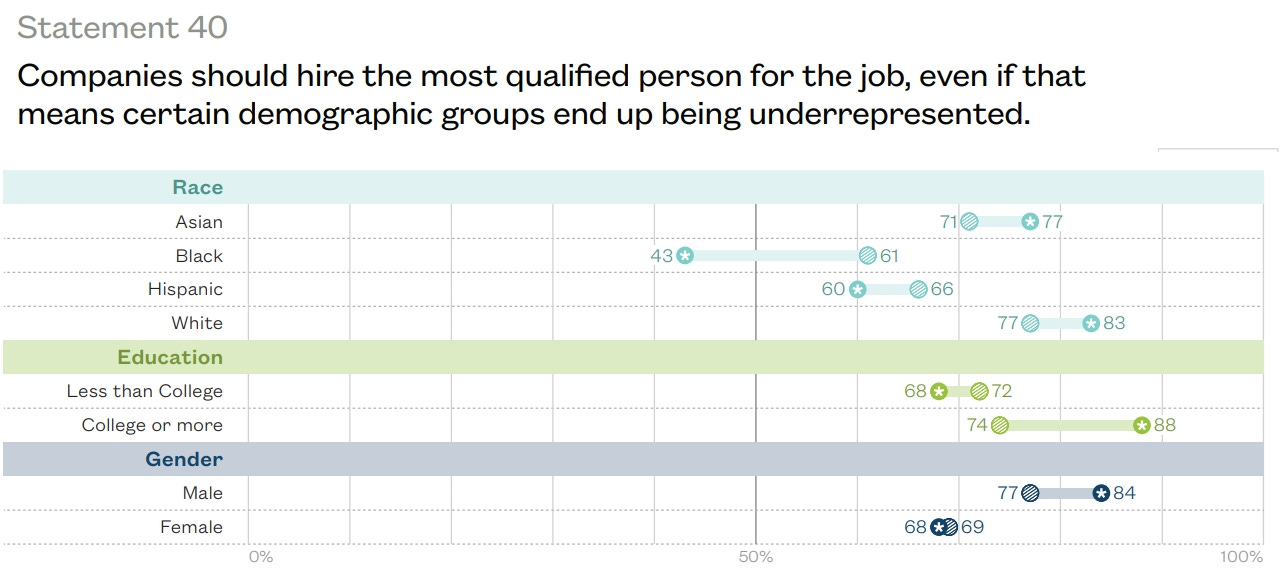

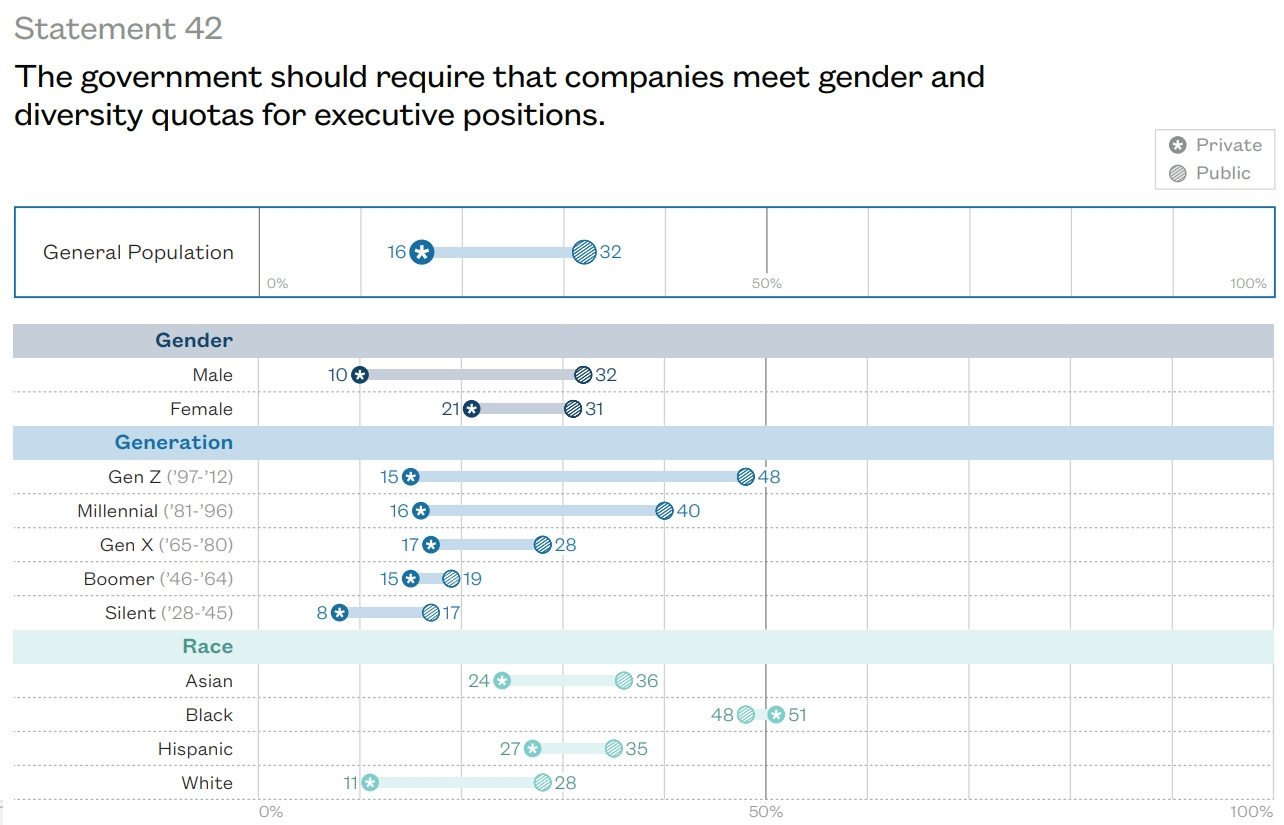

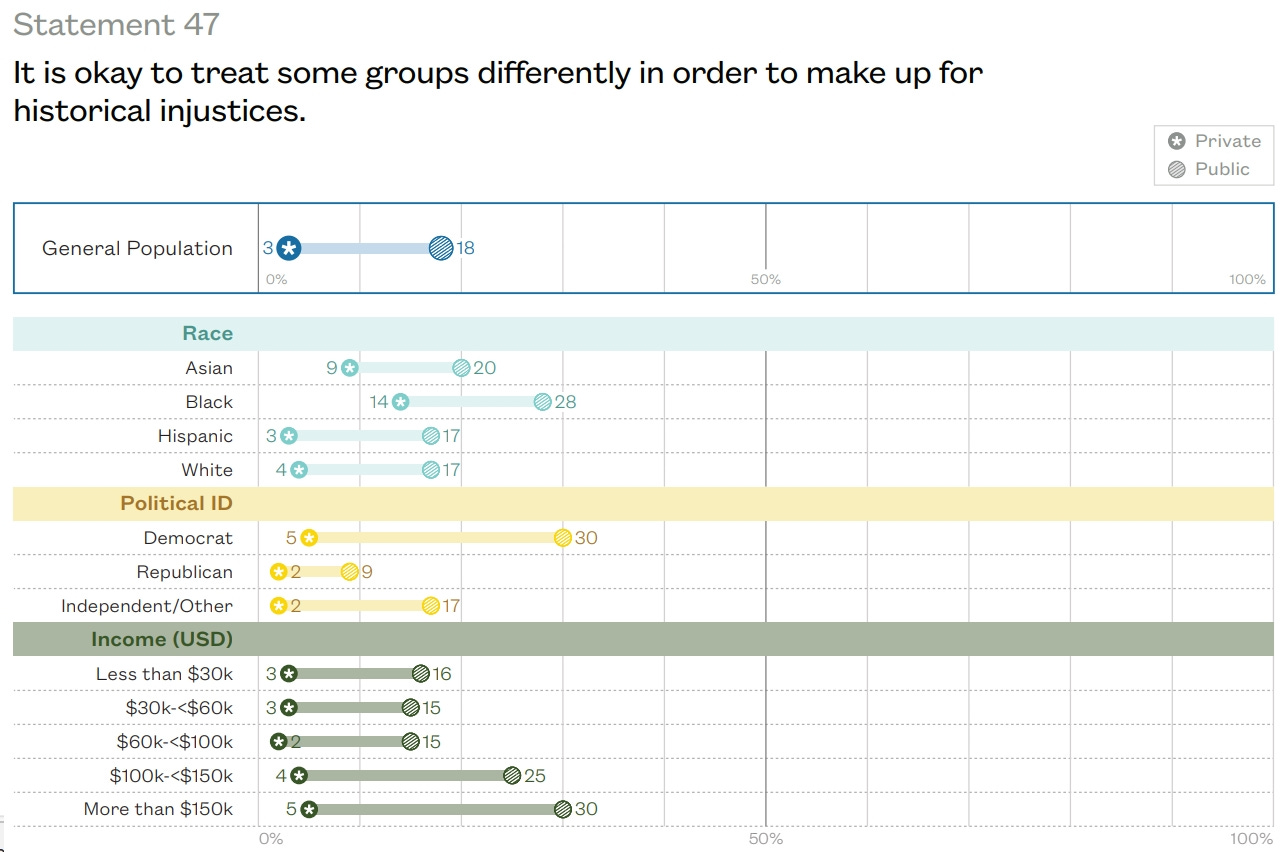

Texiera writes that “Voters know their own views about the value of importance of merit and high achievement. What they may not realize is how far Democrats have strayed from the views of ordinary voters. That cannot stay hidden forever.” Indeed, a 2024 Social Pressure Index (SPI) report – an opinion research study that reveals Americans’ true opinions about sensitive topics from a nationally representative sample of American adults, including more than 19,000 completed responses -- was conducted by the think tank Populace. The purpose of the survey is to estimate the gap between Americans’ privately held beliefs and their publicly stated opinions. It found the following high support for applying merit in the following survey questions and answers:

That concludes this essay series on merit and society.