In his book Fossil Future: Why Global Human Flourishing Requires More Oil, Coal, and Natural Gas – Not Less, Alex Epstein describes the failure of the media (which Epstein terms “our knowledge system”) to consider very significant aspects of any solution proposed to address “climate change”:

There are two major ways in which our knowledge system’s method of evaluation can go wrong—often catastrophically wrong—which we must be constantly vigilant for: (1) using an anti-human “standard of evaluation” and (2) failing to consider the full context. An evaluator’s “standard of evaluation” is the standard or metric by which they evaluate a given phenomenon or policy as good or bad. Standards of evaluation can be pro-human (for example, I use the standard of “advancing human flourishing”) but also anti-human (for example, the elevation of a particular race or class at the expense of the rest of humanity) … Whenever we are evaluating what to do about a product or technology, in order to consider the full context we need to carefully consider not only the negative side-effects but also the benefits … Prior to 2007, the year I started studying energy in depth, I didn’t think our knowledge system was ignoring the massive benefits of fossil fuels, because I didn’t think there were really any significant, let alone massive, benefits of fossil fuels. One reason is that I simply didn’t think much about the benefits of energy. I grew up in a liberal area (Chevy Chase, MD) and attended mainstream schools, so the value of energy was never a subject I was taught about—nor was it a subject that the media talked about. The second reason I didn’t think continuing fossil fuel use had significant benefits is that I considered different forms of energy—whether oil, solar, nuclear, or wind—as more or less interchangeable in their benefits. So rapidly eliminating fossil fuels didn’t seem like it involved any harm, because alternatives could do everything fossil fuels could do, at the same cost, just without the side-effects. But when I started studying energy, I learned three crucial, undeniable facts about the benefits of fossil fuels that hold true to this day—and yet are ignored by our knowledge system when it advocates for the rapid elimination of fossil fuels. These facts are: Fossil fuels are a uniquely cost-effective source of energy. Cost-effective energy is essential to human flourishing. Billions of people are suffering and dying for lack of cost-effective energy.

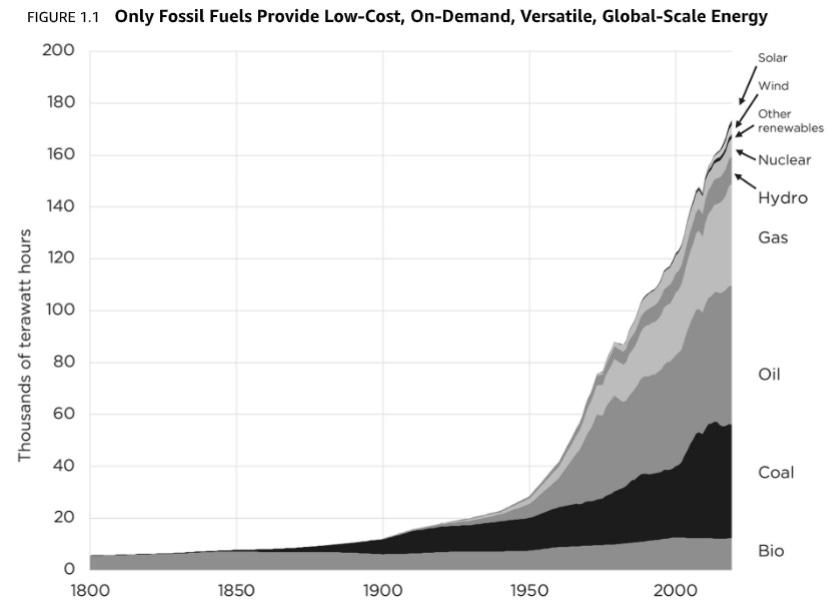

Fossil fuels remain so cost-effective that their use continues to dominate the world of current energy-users:

[A]lternatives such as solar and wind have been fiercely trying to compete with fossil fuels for over fifty years, and yet fossil fuels still provide 80 percent of the world’s energy—four times as much as every alternative combined—and are growing fast … Solar and wind are currently nowhere close to fossil fuels. They provide just 3 percent of the world’s energy, despite having been on the market for many decades and despite governments worldwide aggressively subsidizing or mandating them. And that 3 percent is almost exclusively for electricity, which is less than one fifth of the world’s energy use. Solar and wind energy make almost no contribution to many crucial areas of energy that are dominated by fossil fuels, such as heavy-duty transportation and many forms of “industrial process heat”—generating very high levels of heat for such processes as making plastics and cement.

Epstein points out the often overlooked versatility of fossil fuels in energy delivery:

Why are fossil fuels so dominant and growing fast? Because they are a uniquely cost-effective source of energy—meaning they can provide the most valuable (“effective”) types of energy for the lowest cost for the most people. The cost-effectiveness of energy has four dimensions: Affordability: How much money does it cost relative to how much money people have? Reliability: To what extent can it be produced “on demand”—when needed, in as large a quantity as needed? Versatility: How wide a variety of machines can it power? Scalability: How many people can it produce energy for and in how many places? Fossil fuels alone provide what I call ultra-cost-effective energy, energy that nails all four criteria of cost-effectiveness. Fossil fuel energy is (1) low cost, (2) on-demand, (3) incredibly versatile, and (4) on a scale of billions of people in thousands of places. No other source of energy comes close. The basic reason … is that fossil fuels have remarkable natural attributes—they are naturally stored, naturally concentrated, naturally abundant energy—that energy producers have spent generations figuring out how to harness cost-effectively.

China’s recent economic growth is fueled largely by fossil fuels:

The unique cost-effectiveness of fossil fuels is reflected in the actions and plans of China, the nation arguably most concerned with cost-effective energy.

FIGURE 1.1 Only Fossil Fuels Provide Low-Cost, On-Demand, Versatile, Global-Scale Energy Source: Our World in Data; Vaclav Smil (2017); BP Statistical Review of World Energy.

While in the U.S. we are told that China is “eating our lunch” with solar and wind, the reality is that China’s energy production is 85 percent fossil-fueled. China is “eating our lunch” not in using solar and wind but in using fossil fuels—including electricity that is 64 percent coal—to produce the energy its growing economy requires … As of July 2021, China had 260 gigawatts’ worth of coal plants in development—enough to generate over three times the amount of electricity Texas uses in a year—with each coal plant designed to last forty-plus years.

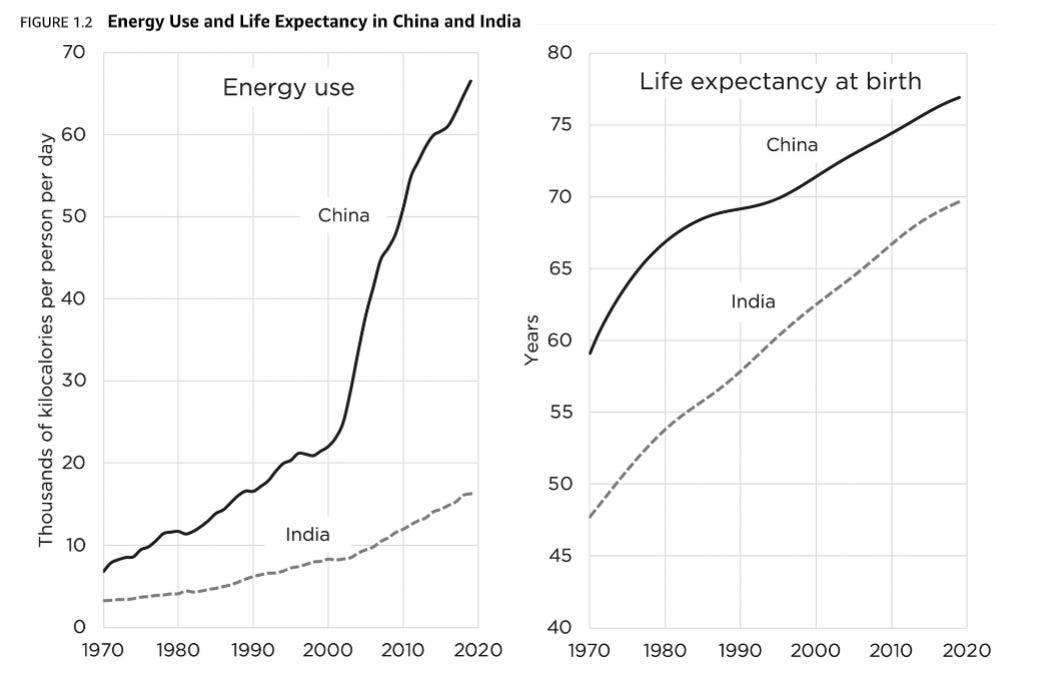

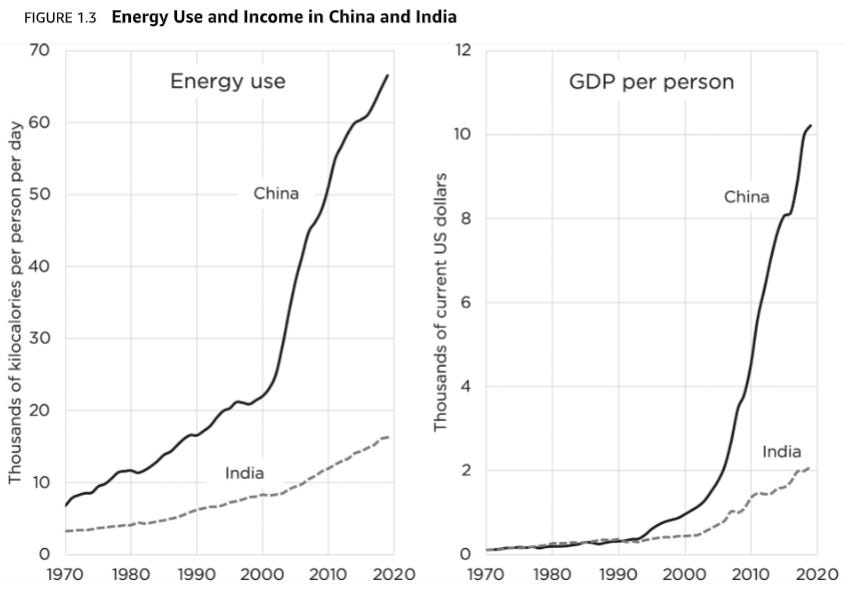

And the benefits of fossil fuel use in China and India include increases in income and life expectancy:

In physics, we learn that “energy” is “the capacity to do work.” When we’re talking about the kind of energy that fossil fuels provide, we’re talking specifically about machine energy—the capacity of machines to do work. I find it clarifying to think of energy as “machine food” or “machine calories.” … [I]n the U.S., the average person uses about seventy-five times more “machine calories” than food calories—which means we have, in effect, seventy-five “machine laborers” producing value for us 24/7. Today’s enormous use of machine labor is only possible because today’s machine food—energy—is so cost-effective … [T]he massive benefits of cost-effective energy in general, and ultra-cost-effective fossil fuel energy in particular, are almost never discussed—while the negative side-effects are always discussed … China and India have been responsible for a great deal of the world’s increasing fossil fuel use over the past several decades. In both countries, both coal and oil use increased by at least a factor of five, producing the vast majority of their energy. While accounts of these countries’ fossil fuel use tend to focus on the negative side-effects, such as air pollution, there have been massive life-extending and life-enhancing benefits. Consider the following graphs showing energy use in China and India correlating with major increases in life expectancy and income.

Not only in China and India but worldwide, hundreds of millions of individuals in industrializing countries have used fossil-fueled machine labor to be productive enough to enjoy their first light bulb, their first refrigerator, their first decent-paying job, their first year with clean drinking water or a full stomach. And yet our knowledge system’s evaluations of China’s and India’s energy use are almost exclusively focused on the negative side-effects of coal and oil, while the role of coal and oil in radically extending lives and increasing opportunity for literally billions of people is ignored.

The benefits of fossil fuels are largely ignored in analyses of climate policies, yet China and India’s experience with fossil fuels also highlights what so much of the rest of the world is lacking. As Epstein explains:

Here’s a scary fact that we almost never hear: Over 3 billion people use almost no energy, including electricity. I call these people members of the “unempowered world.” As energy expert Robert Bryce has observed, the average person in the unempowered world uses less electricity than a typical American refrigerator. And almost 800 million people in the unempowered world are classified by the International Energy Agency (IEA) as having no access to electricity— which, as we saw with the babies in The Gambia who died from the lack of an ultrasound machine or an incubator, is an early death sentence. And 2.4 billion people, mostly part of the unempowered world, use primarily wood and animal dung to cook and to heat their homes. A knowledge system rationally evaluating policy options would not discuss the idea of restricting, let alone eliminating, fossil fuel use without stressing that (1) fossil fuels are currently a uniquely cost-effective source of energy, (2) cost-effective energy is essential to human flourishing, and (3) billions of people are suffering and dying for lack of cost-effective energy. The fact that our knowledge system routinely calls for fossil fuel elimination while ignoring all three of these undeniable benefits suggests that this is one of those times in history where the knowledge system’s “expert” evaluation involves an egregiously irrational method of evaluation—in this case, calling for the elimination of something while ignoring its massive, life-or-death benefits.

To illustrate further, Vaclav Smil writes in his book How the World Really Works: The Science Behind How We Got Here and Where We're Going:

[I]n 2020 the average annual per capita energy supply of about 40 percent of the world’s population (3.1 billion people, which includes nearly all people in sub-Saharan Africa) was no higher than the rate achieved in both Germany and France in 1860! In order to approach the threshold of a dignified standard of living, those 3.1 billion people will need at least to double—but preferably triple—their per capita energy use, and in doing so multiply their electricity supply, boost their food production, and build essential urban, industrial, and transportation infrastructures.

And while the benefits of fossil fuel use are widely ignored, so, too, are sources of energy that don’t emit carbon dioxide. As Epstein writes:

[O]ur knowledge system doesn’t just support the elimination of fossil fuels while ignoring their benefits; it does the same for other vital forms of energy that don’t emit CO2 … [O]ur knowledge system, including our designated experts, regularly supports the elimination of the two most cost-effective, non-CO2-emitting alternatives to fossil fuels—alternatives you would expect anyone concerned about CO2 to eagerly champion: nuclear energy and hydroelectric energy … Nuclear energy … has demonstrated by far the most potential as an alternative to fossil fuels. Like fossil fuels, it harnesses a naturally stored, concentrated, and abundant form of energy. It has a track record of producing relatively low-cost, extremely reliable electricity around the world. It has even shown promising applications for industrial-process heat and heavy-duty transportation (it already powers aircraft carriers, submarines, and giant icebreakers). Nuclear energy emits no CO2 and … has by far the best safety track record of any form of energy. Yet despite the claim that CO2 emissions are the world’s biggest problem, and nuclear energy’s demonstrated ability to lower them, much of our knowledge system and many of our leading designated experts … have fought vehemently to eliminate nuclear energy … Opposition to nuclear energy has been so successful at imposing onerous regulations, project delays, and lawsuits that nuclear energy is declining in the U.S. and threatens to decline around the world.

As Epstein summarizes:

A knowledge system that advocates eliminating cost-effective sources of energy by focusing exclusively on their side-effects while ignoring their benefits is a broken knowledge system, even if it is right about their side-effects. Just as a knowledge system that advocates for the elimination of vaccines and antibiotics on the basis of their side-effects, while ignoring the profound benefits of inoculating and curing disease, is a broken knowledge system for evaluating vaccines and antibiotics—even if it gets the side-effects right.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll continue to examine Epstein’s case for a “Fossil Future.”