Measurement (and Climate Change Predictions) – Part 4

The record of climate change models (and their spokespeople).

In her book Escape from Model Land: How Mathematical Models Can Lead Us Astray and What We Can Do About It, Erica Thompson describes the sheer number of the sort of computer calculations that have to go into models for them to be reasonably expected to yield even the most remotely accurate predictions about something as complex as the global climate:

Large and complex models may have many parameters that can be varied, and the complexity of doing so increases combinatorially. Taking a basic approach and varying each parameter with just a ‘high’, ‘low’ and ‘central’ value, with one parameter we need to do three model runs, with two parameters nine, with three parameters twenty-seven; by the time you have twenty parameters you would need 3,486,784,401 runs. For a model that takes one second to run, that’s 776 years of computation. If you have access to a supercomputer, you can run a lot in parallel and get an answer pretty quickly, but the linear advantages of parallel processing are quickly eaten up by varying a few extra parameters.

In his book Fossil Future: Why Global Human Flourishing Requires More Oil, Coal, and Natural Gas – Not Less, Alex Epstein writes:

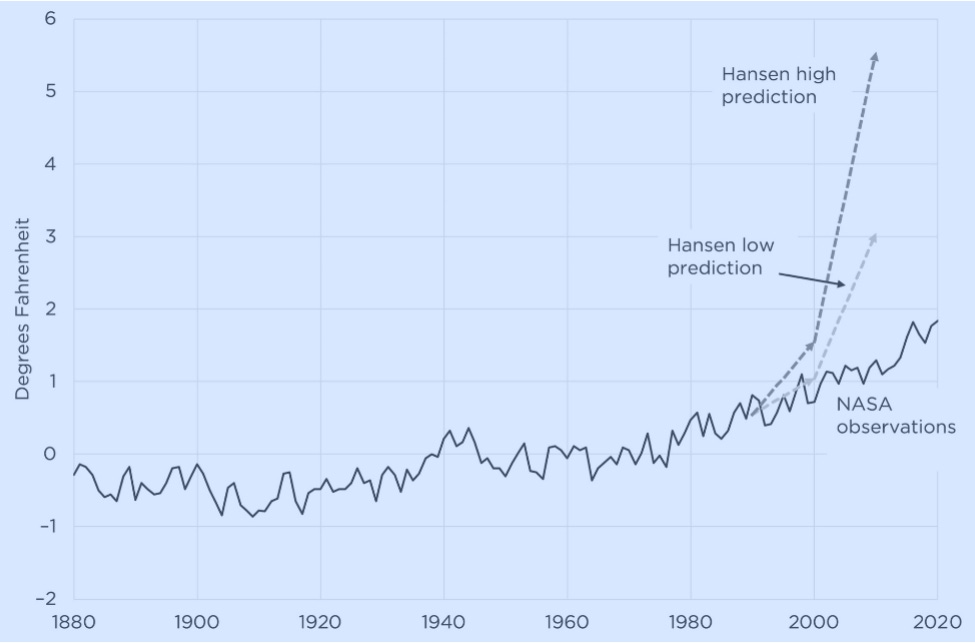

While it is hard to directly assess the validity of our knowledge system’s predictions about the future of climate, it is both far easier and highly informative to assess our knowledge system’s, including designated experts’, track record of climate prediction. The track record of an institution or person tells us a lot about how good their thinking methods are, especially how good their predictions are, and how much they deserve to be relied upon today … [A] study of our knowledge system’s track record on climate reveals that not only has it not been right about climate, it has been 180 degrees wrong … Take James Hansen, arguably the most influential designated expert on climate science. Here’s a 1986 New York Times story about a prediction by him: “Dr. James E. Hansen of the Goddard Space Flight Center’s Institute for Space Studies said research by his institute showed that because of the “greenhouse effect” that results when gases prevent heat from escaping the earth’s atmosphere, global temperatures would rise early in the next century … Average global temperatures would rise by one-half a degree to one degree Fahrenheit [0.28–0.56°C] from 1990 to 2000 if current trends are unchanged, according to Dr. Hansen’s findings. Dr. Hansen said the global temperature would rise by another 2 to 4 degrees [1.11–2.22°C] in the following decade.” Here’s a chart of Hansen’s public prediction versus reality, based on data from the NASA department he ran for decades. Hansen predicted a 0.5–1.0°F (0.28–0.56°C) change in the 1990s—and the reality was a 0.12°C change. That’s off by a factor of two to four. Hansen predicted a 1–2°C change in the 2000s, and the reality was 0.19°C—overstated by a factor of five to ten!

FIGURE 2.1 James Hansen’s Public Prediction vs. Reality Sources: NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies; Philip Shabecoff, The New York Times

John Holdren, President Barack Obama’s top science adviser, had a particularly dire prediction, according to close collaborator Paul Ehrlich [wrote in his book The Machinery of Nature] in 1986: “As University of California physicist John Holdren has said, it is possible that carbon-dioxide climate-induced famines could kill as many as a billion people before the year 2020.”

Epstein then describes the extent to which dire climate predictions have been off the mark:

Given that our knowledge system is continually conveying that climate is getting more dangerous, when I first researched this issue, I knew that Holdren’s prediction was a wild overestimate -- but I figured it was still in the right direction. Climate deaths had to be increasing. But then I learned a fact that changed my perspective from that point on. Early on in my research on fossil fuels, I was fortunate enough to come across an international nonpartisan data set (the International Disaster Database) that keeps a record of disasters and their impacts, including climate-related disasters such as droughts, floods, storms, and extreme temperatures—all the things that are supposedly getting worse.

FIGURE 2.2 More Fossil Fuel Use, Plummeting Climate-Related Disaster Deaths Sources: Scripps Institution of Oceanography; EM-DAT; World Bank Data; Maddison Project Database.

Here’s what blew my mind: over the last century, as CO2 emissions have most rapidly increased, the climate disaster death rate fell by an incredible 98 percent. That means the average person is fifty times less likely to die of a climate-related cause than they were in the 1920s … [N]othing positive in climate conditions could possibly have happened that could explain our being fifty times safer from climate danger. The dramatic change has to be an improvement in our ability to protect ourselves from climate dangers such as extreme temperatures, drought, storms, floods, and wildfires.

And what allowed us to get so much better at protecting ourselves from an always-changing climate? Interestingly, it’s the very thing most climate policy experts seek to limit:

[F]ossil-fueled machine labor. We use fossil-fueled construction machines to build sturdy buildings. We use fossil-fueled heating machines to produce warmth when it’s cold and fossil-fueled cooling machines to produce cool air when it’s hot. We use fossil-fueled irrigation machines to alleviate drought. To put the relationship between fossil fuels and our safety from climate in a sentence: ultra-cost-effective fossil fuel energy powers the machines that produce unprecedented protection from climate … [T]he history of climate safety shows that fossil-fueled machine labor makes us far safer from climate—a phenomenon I call “climate mastery.” … And, as we’ll see, fossil-fueled machine labor makes possible other types of environmental mastery, such as transforming naturally dirty water into unnaturally clean water … While our knowledge system [the term Epstein uses to describe general media coverage of the issue] warned that the pollution side-effects of fossil fuel use would make water worse and worse, in fact, water quality has gotten far better around the world—thanks in large part to fossil fuels. While fossil fuels can certainly contaminate water, human ingenuity makes us better and better at producing more fossil fuel energy with less pollution … Thus predictions that water-pollution problems from fossil fuels would be worse and worse were just wrong. That said, the most significant way in which fossil fuels have contributed to improving water quality is not the decline in their own water pollution but rather their use in producing unprecedented amounts of clean water around the world … Expanded fossil fuel use has powered the construction and operation of water-pumping systems that can bring water from where it is to where it’s needed, and water-purification systems that can transform dirty water into drinkable water … Now let’s look at air quality. On the following page are measurements from the EPA of six major air pollutants. As fossil fuel use goes up, they go down. What happened? Ingenious human beings figured out ways to produce more fossil fuel with less pollution—that is, to reduce the side-effects of fossil fuels through environmental mastery.

FIGURE 2.5 U.S. Air Pollution Goes Down Despite Increasing Fossil Fuel Use Source: U.S. EPA.

One other respect in which fossil fuels have led to improved air quality is in replacing dirtier fuels, namely the wood and animal dung that dominate the poorest parts of the world. Because everyone needs energy for heating and cooking, and wood and dung, often burned indoors, are usually the sources people default to, the use of fossil fuels to replace wood and dung has improved air quality for hundreds of millions of people. Expanding fossil fuel use is a major reason why the World Bank statistic “access to clean fuels and technologies for cooking” increased from 49 percent of the world in 2000 to 59 percent in 2016. That’s some 750 million people who now breathe far cleaner air— yet another ignored benefit of fossil fuel use.

In the next series of essays, we’ll continue to explore how generally cited experts in the field of climate change have failed to consider a surprising number of other highly relevant issues when assessing solutions to any rising global temperatures.

Paul, I just increasingly love what you do. This is one of the best reads I have seen to fold people into understanding why the climate grift is so untenable...a difficult proposition against strong headwinds. I have distributed it widely...hope it gets you some more readers. And I cannot wait for the next installment. Great follow-on to the baseline set by the measurement articles. Many thanks.