Physics and Pluralism Both Rely on Rejecting Essentialism

Separating the universe into separate categories is bad science, and separating people into separate categories is bad social science.

I was recently reading Douglas Murray’s book War on the West, which tracks the modern trajectory of identity politics through, among other things, the New York Times bestselling books White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo and How to Be An Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi.

As Murray writes of DiAngelo (quoting her work):

[I]t had been thought until the fairly recent past to be at the very least rude to condemn people for traits over which they had no say and claim that these traits were in fact without any merits at all. But DiAngelo enjoyed breaking that ethic too. “There are many positive approaches to antiracist work,” she wrote. “One of them is to try to develop a positive white identity ... However, a positive white identity is an impossible goal. White identity is inherently racist; white people do not exist outside the system of white supremacy.” … And then she went on … to list the things that all white people think, believe, and do—such as to claim that “Anti-blackness is foundational to our very identities as white people.” If DiAngelo knew that what she was doing was in some way bad, she didn’t seem to mind it. In fact, she happily admitted to it, writing, “I am breaking a cardinal rule of individualism—I am generalizing.”

And as he writes of Kendi (quoting his work):

Kendi is not opposed to racism. He is opposed to certain forms of racism: specifically white on black racism. Other racisms can be, in his own definitions, a positive force. For instance, in his writing on discrimination and inequity, he cannot avoid one particular conclusion beckoning to him: “The only remedy to racist discrimination is antiracist discrimination. The only remedy to past discrimination is present discrimination. The only remedy to present discrimination is future discrimination.”

DiAngelo and Kendi both focus exclusively on race to explain society with the same sort of religious zeal the old Catholic Church used when focusing on Aristotelianism as the exclusive explanation of our solar system. Aristotle posited a kind of essentialism in which all objects have a substance that make the thing what it is, and without which it would not be a unique kind of thing. In Aristotle’s view, the Earth was unique in that it was the center of the universe. Aristotle was a great thinker for his time, but he was wrong about the Earth, among many other things. (Despite generally being a pretty keen observer of his surroundings, he made many mistakes, perhaps most famously in stating men had more teeth than women, an inaccurate belief he could have disabused himself of by simply counting men’s and women’s teeth more carefully, if he counted them at all.)

DiAngelo and Kendi, too, err in supporting racial essentialism based on failures to gather available data that would provide necessary context. DiAngelo writes “Whites enact racism [by] [a]ttributing inequality between whites and people of color to [any] causes other than racism.” And Kendi has said “When I see racial disparities, I see racism.” Both attribute continued disparities solely to an essentially racist majority white society, ignoring many other explanations. Positing the false notion that disparities in outcomes among people grouped by race are explainable only by racism is a form of essentialism that should look as silly to us today as the church-imposed Aristotelianism of the past.

At about the same time I was reading Murray’s War on the West, I was also reading James Gleik’s book Genius, a wonderful biography of the great physicist Richard Feynman. In the book, Gleik describes the young Feynman’s attending the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair. The fair featured a Hall of Science, on one wall of which was inscribed a 151-word summary of the state of science to that time. The book doesn’t quote the summary, but I looked it up, and it read:

Pythagoras named the cosmos; Euclid shaped geometry ... Archimedes physics. Xenophanes gazing upon the Heavens saw them to be one. Copernicus placed central in that one, our shining sun. In the motions of physical bodies Galileo beheld law; thence Newton and the principle of universal gravitation. Democritus glimpsed the atomic theory of the structure of matter; Dalton established it. When in the nineteenth century Lamarck and Darwin formulated the great principle of organic evolution, the science of life was first seen as a cosmic progression of nature. For the saving of life through inoculation men give honor to Jenner and Pasteur. The century of progress saw Oersted and Faraday set forth, and Maxwell and Hertz advance the theory of electromagnetism. Through the labors of Becquerel, of the Curies and of Thomson, to our own day are revealed fragile atoms and electrons. Planck’s quantum and Einstein’s relativity theory open new epochs to science.

In that short summary, we can see how the path of science is toward explaining ever more and more different phenomena under ever-expanding theories, all of which explain one phenomenon or other, while, at the same time, accounting for the theories coming before as well. The search is for unifying theories. Math, once reserved for numeric accounting, became the universal language of physics and the movement of things, including planets, and was used to describe exactly how planets move and how things move around planets. Electricity and magnetism were seen as two separate things, until it was discovered they were both actually a force called electromagnetism, two sides of the same coin. Quantum theory and the chemistry of atoms and molecules describe how things combine and separate, and more successful ways of combining and separating is what propels things forward in evolutionary history. Over and over again, we see how science takes in all aspects of the universe as we know it and builds on its previous discoveries by finding ways to explain new phenomena without violating other well-founded physical principles.

The essence of science is to discover uniform rules that describe how, amidst a variety of different forces, the universe is still kept together. As one of the quotes (by science historian Francis Sidney Marvin) at the 1933 World’s Fair’s Hall of Science stated: “The essence of science is to discover identity in difference.” Similarly, it strikes me that the essence of any social science that seeks to discern how best pluralism might be fostered in free societies should include the search for principles tending to help societies stay together even when they’re composed of different people — that is, to also “discovery identity in difference.” Whatever DiAngelo and Kendi are practicing, it’s not a social science aimed at keeping societies together by promoting pluralism, but instead a form of identity essentialism that can only keep people apart in separate racial categories.

Galileo was put on trial by the Catholic Church for contradicting the Church’s false Aristotelian view that the Earth was the center of the universe. And of course, the Church’s promotion of a theory that posited one explanation for how one part of the universe worked that was fundamentally at odds with other explanations of how other parts of the universe worked was bad science. Still, I have no objection to Aristotle’s works being taught in schools, as long as his theories of essentialism are questioned and put into broader context.

I also have no objection to the works of DiAngelo and Kendi being taught in schools — as long as they’re put in context as well and taught as part of lessons exploring the problems posed to pluralist societies by racially essentialist views, be they the racial essentialism of DiAngelo, Kendi, or the Ku Klux Klan.

And as Coleman Hughes points out, Bayard Rustin, a key ally of Martin Luther King, wrote:

In the past few years, I have seen all too many blacks fall into the trap of calling any white person who disagrees with them a racist. I have always considered this practice unethical as well as a sign of deep insecurity … It follows from this introduction of ad hominem attacks into political discourse that a white person cannot talk about problems affecting blacks and vice versa, Pittsburghers cannot talk about problems affecting New Yorkers and vice versa, and on and on ad infinitum. People who engage in such attacks may want a just society, but they will build no more than a tower of Babel.

Indeed, the path of identity politics leads not to truth, but to ad hominem attacks.

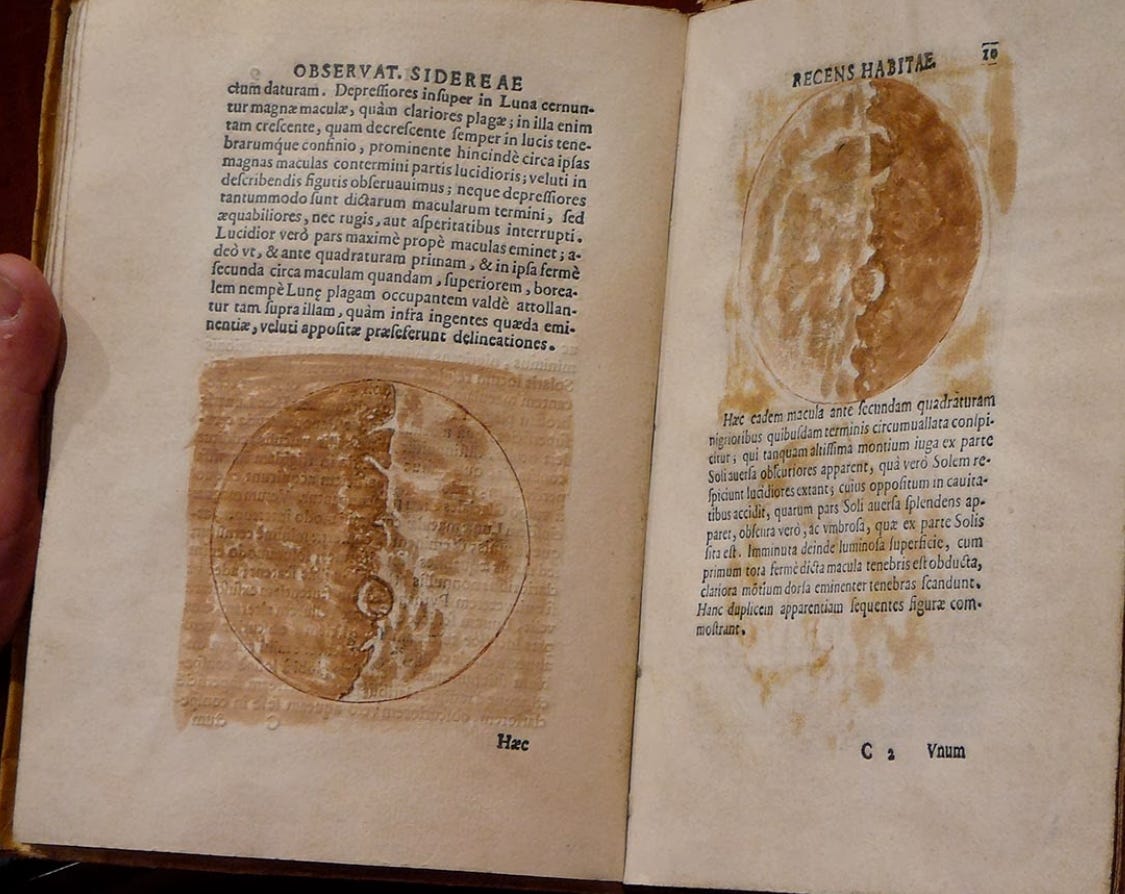

As Edward Tufte writes in Beautiful Evidence, “Galileo also published Siderius Nuncius, which presents 5 engraved images of the moon … the first astronomical pictures ever printed. A major scientific finding is that the moon:

[is] not smooth, even, and perfectly spherical, as the great crowd of philosophers have believed about this and other heavenly bodies, but, on the contrary, [is] uneven, rough, and crowded with depressions and bulges. And it is like the face of the Earth itself, which is marked here which is marked here and there with chains of mountains and depths of valleys.

Tufte continues, “In 1610 the discovery of such irregularities was significant because Aristotle had claimed that all celestial bodies were perfect, smooth, and without blemish (unlike the wretched Earth). This evidence-free fancy had become religious doctrine before being demolished by 10 pages of visual observations reported in Siderius Nuncius.”

In the same way, much public policy relates to multiple underlying issues that aren’t amenable to solutions based on optimistically superficial slogans painted in black-and-white, but rather appropriately addressed only by thorough assessments of all the gradations under and around various social problems.

Where would the Kendis and DiAngelos be without "post hoc, ergo propter hoc"?

Kendi & DiAngelo are just vile racists. It's very hard to devote any time to thinking about or discussing them.