Continuing this essay series on happiness, primarily with reference to Wellbeing: Science and Policy, by Richard Layard and Jan-Emmanuel De Neve, and Blind Spot: The Global Rise of Unhappiness and How Leaders Missed It, by Jon Clifton, the head of the Gallup polling organization, this essay focuses on one of the five main element of wellbeing, namely income, and also on the pernicious effects of status-seeking on wellbeing.

As Layard and De Never write, as long as one is making enough income to avoid living in extreme poverty, income makes less difference for happiness than many people realize:

[I]ncome differences explain some 2% of the variance of life satisfaction within countries – much less than the 20% explained by mental health, physical health and human relationships … As between individuals, three central findings of wellbeing research are these: (1) In every country, richer people are on average happier than poorer people. (2) This difference is quite small and explains around 2% of the variance of wellbeing within the population. (3) The effect of additional income gets smaller, the richer you are … Extra income makes more difference to wellbeing at the bottom (left-hand) end of the scale than it does at the upper end of the scale. An extra $ of income produces a smaller and smaller amount of extra wellbeing the richer the person is. This old idea is now called “the diminishing marginal utility of income” … As Table 13.1 shows, the effects [of income on happiness] are not large. To take the US case, one additional point of log income, corresponding to nearly a tripling of income, will produce an extra 0.31 points of wellbeing (out of 10 points maximum).

… As Figure 13.3 shows, average happiness has not increased there since the 1950s, despite rapid economic growth that was widely shared at least till the 1970s.

However, Figure 13.3 does not prove that in the United States higher income did not improve wellbeing. It might have done so, with other factors offsetting this effect.

Things get very interesting when one begins to examine the loss of wellbeing people experience, not as a result of low income, but as a result of their own envy-driven dissatisfaction with the fact that other people might make more money than they do. As Layard and De Neve write:

There is abundant evidence (including experimental evidence) that people are less satisfied with a given income the higher the income level of other people … There is one obvious reason why national increases in income over time might produce lower changes in wellbeing than individual increases in income at one point in time. It is social comparisons. Suppose that each of us has a comparator group with whom we compare our incomes and that much of our concern about income is focused on our relative income rather than our absolute income. Then a person’s wellbeing depends positively on her wellbeing but negatively on the income of her comparators … So what is the evidence on the effect of comparator income? In the great majority of studies, it is negative and large … When an individual has a higher income, holding constant, she is happier. This is mainly because her relative income is higher. But when the whole society becomes richer, rises and relative incomes do not change. (Some people may go up in relative terms and others down but the average of relative income remains constant.) So at the level of society the only effect of economic growth is the weaker effect of absolute income … There is much other evidence that people care about relative income as well as absolute income. Some of it comes from neuroscience, led by Armin Falk of the University of Bonn. His team organised an experiment where participants had to undertake a task while undergoing a functional MRI measurement of brain activity in the brain’s reward centre, the ventral striatum. Those who successfully completed the task were given a financial reward, which was varied randomly. They were also told of the reward, if any, received by the person with whom they were paired. The findings were remarkable. The measure of activity in the ventral striatum increased by 0.92 units for every € 100 they themselves received and fell by 0.67 units for every € 100 their pair received. So, relative income had double the effect of absolute income … In another ingenious experiment, David Card (another winner of the Nobel Prize) and his colleagues examined the effect of knowing the incomes of your colleagues. It happened that the University of California, where he works, had recently put all faculty salaries online. But most people did not know about it. So Card informed a random selection of the faculty members that these data existed. He also measured the wellbeing of the treatment and control group before and after he did this. Those who learned about colleagues’ salaries became on average less satisfied. So relative income clearly matters … We reviewed a mass of evidence and concluded that, as a benchmark, a unit increase in log income raises wellbeing by 0.3 points (out of 10). The share of the within country variance in wellbeing explained by income inequality is 3% or less. So income is in no sense a proxy for wellbeing. Across countries, the effect of a unit change in log income per capita (other things equal) is also around 0.3 points of wellbeing. Over time, wellbeing has increased with income in some countries but not in others … From direct studies on individual data, it is clear that in most cases a rise in other people’s income reduces your own wellbeing.

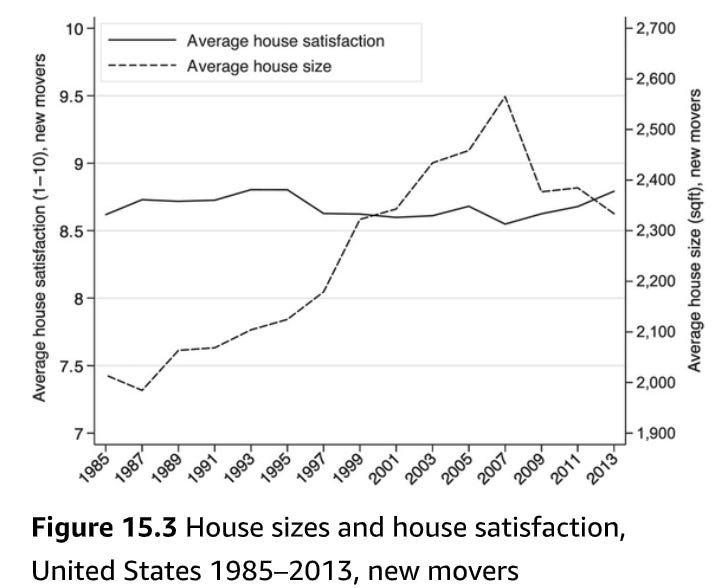

House-envy is also a factor. As Layard and De Neve write:

In the United States, people in larger houses are more satisfied with their house. And over time houses have become bigger – since 1945 they have doubled in size. Yet, despite this, people are no more satisfied with their houses than they were in the 1980s when measurement began (see Figure 15.3).

In a study of single-family houses in US suburbs, a 1% rise in the size of your house increased your satisfaction with your home by 0.08%. But at the same time, a 1% rise in the size of other houses in your area decreased your satisfaction with your home by 0.07% … Clearly Karl Marx was on to something when he wrote: “A house may be large or small: as long as the neighbouring houses are likewise small, it satisfies all social requirements for a residence. But let there arise next to the little house a palace, and the little house shrinks to a hut.” But doesn’t this whole analysis underestimate the importance of housing for our wellbeing? To investigate this issue, the British government used its regular English National Housing Survey to find out how far people’s life satisfaction depended on their housing, other things being equal. Surprisingly, the answer was: little. When life satisfaction was regressed on the standard control variables and housing variables were then introduced, the only really important new influence came from the finance of housing. If you were in arrears on your rent or mortgage, this reduced your life satisfaction by a big 0.60 points (out of 10). But no variables within the home had any significant influence (including overcrowding, damp, disrepair and poor heating).

Of course, what matters most for material wellbeing is simply avoiding subsistence poverty, not how one compares with others regarding income, or house size. So it’s no surprise that people who make fewer income comparisons are happier. As Layard and De Never write, “Another important implication of social comparisons is for us as individuals. People who make fewer comparisons are on average happier. So we should train our tastes, as far as we can, to reduce [the comparisons we make].” Indeed, researchers at Dartmouth, Harvard, and UCLA, reviewing the research, found that unhappy people tend to make more social comparisons, indicating something is lacking inside them that causes them to seek validation in comparisons to others, which they tend to find makes them feel even less happy:

Unhappy people, not happy people, may be the ones who actually make spontaneous frequent social comparisons. In one study, happy and sad people had the opportunity to compare themselves to a better or worse peer. Sad people felt worse when paired with a better performer, and better when paired with a worse performer. Happy people had less affective vulnerability to the available social comparison information; they simply did not pay as much attention to how well others were doing. Similarly, [other researchers] found that unhappy people make more frequent social comparisons, and [still other researchers] found that mildly depressed people made more frequent social comparisons. [Others] found the tendency to seek social comparison information is correlated with low self-esteem, depression and neuroticism … People make social comparisons when they need both to reduce uncertainty about their abilities, performance, and other socially defined attributes, and when they need to rely on an external standard against which to judge themselves. The implication is that people who are uncertain of their self-worth, who do not have clear, internal standards, will engage in frequent social comparisons … People who tend to make spontaneous social comparisons, therefore, tend to be unhappy, more vulnerable to the affective consequences of such comparisons, and more likely to get caught in a cycle of constantly comparing themselves to others, being in a self-focused state, and consequently being unhappy.

(Incidentally, on this topic, every once in a while, other people point out to me that they’ve made an expensive purchase of something or other, and I sometimes let slip that I don’t find the purchase particularly impressive and I wonder aloud if the purchase was really worth it. Some might cringe at such directness, but then again maybe more people should feel free to be honest about their rejection of status-seeking for fear it will offend status-seekers in their own social circle. And interestingly, researchers have found that “people significantly mis-predict [bad] consequences of honesty: focusing on honesty (but not kindness or communication-consciousness) is more pleasurable, meaningful, socially connecting, and does less relational harm than individuals expect … Our results suggest that individuals broadly misunderstand the consequences of increased honesty because they overestimate how negatively others will react to their honesty.”)

Clifton, the head of the Gallup polling organization, adds the following regarding income and happiness:

[A] great life is more than just money. After studying the 20% of people who report having a great life, Gallup finds they have five things in common: They are fulfilled by their work, have little financial stress, live in great communities, have good physical health, and have loved ones they can turn to for help … One of the first global datasets from Gallup led to one of the most influential papers in the discourse of income and wealth. This paper, written by Angus Deaton, … found that people in rich countries do rate their lives better than people in poor countries, which suggests that economic growth does cause people to see their lives better. His analysis revealed a high positive correlation with life evaluation and GDP per capita … [W]e had data on roughly 350,000 Americans each year. We asked people to rate their lives and to report how much they smiled and laughed a lot yesterday or whether they experienced a lot of stress, sadness, and anger. We also asked people how much money they make. Using Gallup’s income variable, [Daniel] Kahneman and Deaton found that the more money people make, the higher they rate their lives. In fact, there did not appear to be a satiation point. Meaning, money never stops affecting how well you see your life. You might think, “There it is — money does buy happiness.” That is true, but only if you believe that true “happiness” is defined by how you see your life. If you think happiness is how you live your life — how much you laugh and smile or how little anger you experience — then this study does not support the theory that money buys happiness.

So it may well be that many people become a bit happier the more money they make, but that could be because they happen to place greater emphasis on their comparative wealth compared to others, thereby gaining happiness -- but only as a result of their irrational personal emphasis on their comparative wealth status.

As Clifton continues:

When the authors looked at the relationship between income and reports of stress, anger, sadness, or enjoyment, they found a much weaker link. Beyond $75,000 of annual salary, income had almost no effect on how people lived their lives. Once your basic needs are met, money cannot buy laughter or a stress-free life … [Further,] [a]cademics at the University of Virginia and Purdue University [used] the same Gallup World Poll data [and] did a similar analysis but controlled for household size (an income of $95,000 may go further if you are single than if you have four kids). They also did not omit some of the highest incomes in the database. They found that income’s influence on life evaluation did satiate: Beyond $95,000 of annual income, people stop rating their lives better. If anything, incomes that are too high may cause people to see their lives worse in some parts of the world. Why would more money make people rate their lives worse? According to the authors: “Theoretically, it is presumably not the higher incomes themselves that drive reductions in [wellbeing], but the costs associated with them. High incomes are usually accompanied by high demands (time, workload, responsibility and so on) that might also limit opportunities for positive experiences (for example, leisure activities). Additional factors may play a role as well, such as an increase in materialistic values, additional material aspirations that may go unfulfilled, increased social comparisons or other life changes in reaction to greater income (for example, more children or living in more expensive neighborhoods). Importantly, the ill effects of the highest incomes may not just be present when one’s maximum income is finally reached, but could also occur in the process of its attainment.”

Although we should strive to disabuse ourselves of tendencies to status-seek and our desire to “keep up with the Joneses,” evolution appears to have left most of us with an unshakable yet irrational dislike of the fact that other people make more money or have more things than we do. As Robin Hanson and Kevin Simler write in their book The Elephant in the Brain: Hidden Motives in Everyday Life:

No matter how fast the economy grows, there remains a limited supply of sex and social status—and earning and spending money is still a good way to compete for it. The idea that we use purchases to flaunt our wealth is known as conspicuous consumption. It’s an accusation that we buy things not so much for purely personal enjoyment as for showing off or “keeping up with the Joneses.” This dynamic has been understood since at least 1899, when Thorstein Veblen published his landmark book The Theory of the Leisure Class. It remains, however, an underappreciated idea, and explains a lot more of our consumer behavior than most people realize … When you think about people two or three rungs above you on the social ladder, especially the nouveau riche, it’s easy to question the utility of their ostentatious purchases. Does anyone really need a 10,000-square-foot house, a $30,000 Patek Philippe watch, or a $500,000 Porsche Carrera GT? Of course not, but the same logic applies to much of your own “luxurious” lifestyle—it’s just harder for you to see. Consider taking the perspective of a mother of six from the slums of Kolkata. To her, your spending habits are just as flashy and grotesque as those of a Saudi prince are to you. Do you really need to spend $20(!!) at Olive Garden to have a team of chefs, servers, bussers, and dishwashers cater to your every whim? Twenty dollars may be more than the family in Kolkata spends on food in an entire week. Of course, it doesn’t feel, to you, like conspicuous consumption. But when a friend invites you out to dinner, it’s nice being able to say yes. (If you had to decline because you couldn’t afford to eat out, you might feel a twinge of shame.) And at the end of the meal, when you leave two uneaten breadsticks on the table, it doesn’t feel at all like conspicuous waste. You’re just thinking, “Why bother?” In fact, you might feel silly asking the waiter to pack them up for you, those two measly pieces of bread. One way or another, we’re all conspicuous consumers. But it’s a lot more than wealth and class that we’re trying to show off with our purchases … Consider why people buy environmentally friendly “green” products. Electric cars typically cost more than gas-powered ones. Disposable forks made from potatoes cost more than those made from plastic, and often bend and break more easily. Conventional wisdom holds that consumers buy green goods—rather than non-green substitutes that are cheaper, more functional, or more luxurious—in order to “help the environment.” But of course we should be skeptical that such purely altruistic motives are the whole story. In 2010, a team of psychologists led by Vladas Griskevicius undertook some experiments to tease out some of these ulterior motives. The researchers gave subjects a choice between two equivalently priced goods, one of them luxurious but non-green, the other green but less luxurious. For example, they gave subjects a choice between two car models, both $30,000 versions of the Honda Accord. The non-green model was a top-of-the-line car with a sporty V-six engine replete with leather seats, GPS navigation system, and all the luxury trimmings. The green model had none of the nice extras, but featured a more eco-friendly hybrid engine. Subjects were also given a choice between two household cleaners (high-powered vs. biodegradable) and two dishwashers (high-end vs. water-saving). Subjects in the control group, who were simply asked which product they’d rather buy, expressed a distinct preference for the luxurious (non-green) product. But subjects in the experimental group were asked for their choice only after being primed with a status-seeking motive. As a result, experimental subjects expressed significantly more interest in the green version of each product. In another experiment, Griskevicius and his team asked subjects to consider buying green or non-green products in two different shopping scenarios. One group was asked to imagine making the purchase online, in the privacy of their homes, while another group was asked to imagine making the purchase in public, out at a store. What they found is that, when subjects are primed with a status motive, they show a stronger preference for green products when shopping in public, and a weaker preference for green products when shopping online. Clearly their motive isn’t just to help the environment, but also to be seen as being helpful … The fact that we often discuss our purchases also explains how we’re able to use services and experiences, in addition to material goods, to advertise our desirable qualities. A trip to the Galápagos isn’t something we can tote around like a handbag, but by telling frequent stories about the trip, bringing home souvenirs, or posting photos to Facebook, we can achieve much of the same effect.

As Hanson and Simler point out:

Now, as consumers, we’re aware of many of these signals. We know how to judge people by their purchases, and we’re mostly aware of the impressions our own purchases make on others. But we’re significantly less aware of the extent to which our purchasing decisions are driven by these signaling motives. To get a better sense for just how much of our consumption is driven by signaling motives (i.e., conspicuous consumption), let’s try to imagine a world where consumption is entirely inconspicuous. Suppose a powerful alien visits Earth and decides to toy with us for its amusement. The alien wields a device capable of reprogramming our entire species. With the push of a little red button, a shock wave will blast across the planet, transfiguring every human in its wake. It will transform not only our brains, but also our genes, so that the change will persist across generations. The particular change the alien has in mind for our species is peculiar … The alien is going to render us oblivious to each other’s possessions. Everything else about our psychology will remain the same, and specifically, we’ll still be able to enjoy our own possessions. But after getting blasted, we’ll cease being able to form meaningful impressions about other people’s things—their clothes, cars, houses, tech gadgets, or anything else. It’s not that these objects will become literally invisible to us. We’ll still be able to perceive and interact with them. We’ll just, somehow, no longer care. In particular, we won’t be able to judge anyone by their possessions, nor will anyone be able to judge us. No one will comment on our clothes anymore or notice if we stop washing our cars. It will render all our purchases completely inconspicuous. And, for what it’s worth, we’ll be completely aware of these changes; we will fully understand the effect the alien had on our species. Let’s call this Obliviation … Here’s the big question: How does Obliviation change our behavior as consumers? First of all, it’s unlikely to change much overnight. We all have entrenched habits that we developed long before the alien’s intervention, many of which will stick with us for a long time, even if they no longer make sense. But after a few years, and certainly after a generation or two, life will look very different. One important consequence is that whole categories of products will disappear as the demand for them slowly evaporates. In Spent, Geoffrey Miller distinguishes between products we buy for personal use, like scissors, brooms, and pillows, and products we buy for showing off, like jewelry and branded apparel (see Table 1). In an Obliviated world, clearly there’s no use for anything in the “showing off” category.

But most products offer a mix of personal value and signaling value. A car, for example, is simultaneously a means of transport and, in many cases, a coveted status symbol. (Witness the wide eyes and fawning coos of friends and family whenever you buy a new car, even a relatively modest one.) After Obliviation, then, we’ll continue to buy cars for transportation, but we’ll base our decisions entirely on functionality, reliability, comfort, and (low) price. Hummers, which are expensive and comically impractical, will lose almost all of their appeal. Lexuses, BMWs, and other higher-end cars may continue to be valued for their quality, but consumers today also pay a premium for the luxury brand—a premium that would soon disappear. Clothes are another product category that’s part function, part fashion. In an Obliviated world, the fashion component will lose all its value. What remains is likely to be the merest fraction of the bewildering variety of clothing items available today. Think about what you wear when you’re home alone—not tight jeans or delicate silk shirts, but comfortable, inexpensive items like T-shirts, sweatpants, and slippers. Today it’s considered inappropriate to wear sweatpants to a dinner party or around the office. But in an Obliviated world, where no one is even capable of noticing, why not? … Housing would also change substantially after Obliviation. Today we’re keenly aware that our homes make impressions on visiting friends and family. So as we shop around for a new house or apartment, we wonder silently to ourselves, “What will my friends think of this place? Is it nice enough? Is it in the right kind of neighborhood?” Similarly, when we buy new rugs, paintings, or furniture, we often do so hoping they’ll be admired … [I]n an Obliviated world, spared from having to worry about what others think, we’ll certainly do many things differently. At the margin, we’ll choose to live in smaller, cheaper homes that require less upkeep. We’ll clean them less, decorate them less, and furnish them more comfortably and cheaply. Living rooms—which are often decorated lavishly with guests in mind, then used only sparingly—will eventually disappear or get repurposed. We’ll also keep smaller yards, landscaped for functionality and ease of maintenance. Many yards, even front yards, will simply be left to the birds … [C]entralized warehouse-stores like Costco Wholesale and IKEA can offer deep discounts on their standardized wares by unlocking economies of scale and centralized distribution. If we weren’t such conspicuous consumers, choosing fashions to carefully match our social and self-images, we could enjoy these same economies of scale for many more of our purchases … Consider the lobster—as David Foster Wallace invites us to do in an essay of the same name. “Up until sometime in the 1800s,” writes Wallace, lobster was literally low-class food, eaten only by the poor and institutionalized. Even in the harsh penal environment of early America, some colonies had laws against feeding lobsters to inmates more than once a week because it was thought to be cruel and unusual, like making people eat rats. One reason for their low status was how plentiful lobsters were in old New England. “Unbelievable abundance” is how one source describes the situation. Today, of course, lobster is far less plentiful and much more expensive, and now it’s considered a delicacy, “only a step or two down from caviar.” A similar aesthetic shift occurred with skin color in Europe. When most people worked outdoors, suntanned skin was disdained as the mark of a low-status laborer. Light skin, in contrast, was prized as a mark of wealth; only the rich could afford to protect their skin by remaining indoors or else carrying parasols. Later, when jobs migrated to factories and offices, lighter skin became common and vulgar, and only the wealthy could afford to lay around soaking in the sun. Now, lobster and suntans may not be “art,” exactly, but we nevertheless experience them aesthetically, and they illustrate how profoundly our tastes can change in response to changes in extrinsic factors. Here, things that were once cheap and easy became precious and difficult, and therefore more valued … Prior to the Industrial Revolution, when most items were made by hand, consumers unequivocally valued technical perfection in their art objects. Paintings and sculptures, for example, were prized for their realism, that is, how accurately they depicted their subject matter. Realism did two things for the viewer: it provided a rare and enjoyable sensory experience (intrinsic properties), and it demonstrated the artist’s virtuosity (extrinsic properties). There was no conflict between these two agendas. This was true across a variety of art forms and (especially) crafts. Symmetry, smooth lines and surfaces, the perfect repetition of geometrical forms—these were the marks of a skilled artisan, and they were valued as such. Then, starting in the mid-18th century, the Industrial Revolution ushered in a new suite of manufacturing techniques. Objects that had previously been made only by hand—a process intensive in both labor and skill—could now be made with the help of machines. This gave artists and artisans unprecedented control over the manufacturing process. Walter Benjamin, a German cultural critic writing in the 1920s and 1930s, called this the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, and it led to an upheaval in aesthetic sensibilities. No longer was intrinsic perfection prized for its own sake. A vase, for example, could now be made smoother and more symmetric than ever before—but that very perfection became the mark of cheap, mass-produced goods. In response, those consumers who could afford handmade goods learned to prefer them, not only in spite of, but because of their imperfections.

As Robin Hanson writes, we also (sadly) often just rely on the status of others rather than evaluating them on the merits.

[W]e rely on status to select, incentivize, and monitor important professionals like teachers, doctors, and lawyers. Instead of allocating them based on measures of on-the-job performance, or giving them incentives to perform well, we more just trust that their status makes them behave well. Famous “halo effects” make us trust them far outside their areas of expertise. Instead of wanting them to be trained by practicing the job they will do, we don’t mind them just competing to impress other high status folks in whatever ways those folks choose.

That concludes this essay series on the science of happiness.

In the next essay series, I’ll take the opportunity to survey many of the topics we’ve previously explored on the Big Picture, and connect some of them together, in an effort to present the Big Picture we face as a nation today.