Continuing this essay series on happiness, primarily with reference to Wellbeing: Science and Policy, by Richard Layard and Jan-Emmanuel De Neve, and Blind Spot: The Global Rise of Unhappiness and How Leaders Missed It, by Jon Clifton, the head of the Gallup polling organization, this essay focuses on one of the five main elements of wellbeing: employment.

As explored in a previous essay, younger people, especially men, are dropping out of the labor force. Yet as Layard and De Neve write:

One of the most robust findings to emerge from wellbeing science is the profound cost of unemployment. Workers who lose their jobs suffer declines in life satisfaction comparable with the death of a spouse. In some cases, those affected fail to recover back to baseline levels of happiness years later, even after returning back to work. The wellbeing consequences of unemployment are about much more than lost wages. Work can provide us with a sense of meaning in life, a source of human connection, social status and routine. When we lose a job, we lose much more than a pay check. As a result, for policy-makers interested in promoting and supporting wellbeing, reducing unemployment ought be a top priority (and finding ways to do this without increasing inflation).

Modern fiscal policy, unfortunately, had tended to dramatically increase inflation. As the Wall Street Journal reports:

[I]n March 2021, Democrats stoked consumption even more with their $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan Act, even as states were lifting lockdowns and vaccines rolled out. The bill was largely composed of transfer payments, including $1,400 checks per person, $3,600 per child tax credits, an extra $300 a week in unemployment benefits, a 15% increase in food stamps, rental assistance and more. Such handouts discouraged unemployed Americans from returning to work since they could earn as much not working.

Layard and De Neve go on to address how important work is to wellbeing:

To begin answering this question, we can look at average differences in wellbeing between people according to their employment status. In Figure 11.1, these differences are plotted for six large countries using data from the Gallup World Poll. Here, we consider differences in life satisfaction between adults employed full-time, part-time, self-employed, underemployed, unemployed, and out of the labour force. In this case, “underemployed” means working part-time but wanting to work full-time, and “out of the labour force” means not having a job and not actively looking for one. This last category is mainly composed of homemakers, early retirees, students and those unable to work due to disability.

As Figure 11.1, shows, unemployed people are less happy on average than employed people in every country. The crude difference is over 1 point (out of 10) in the United States and the UK and rather less in poorer countries … For both men and women, unemployment substantially reduces life satisfaction on top of the effect through lost income. The negative effect of unemployment is roughly 30% larger for men than women, a trend generally reflected in the literature. Importantly, workers who remain unemployed for longer periods of time struggle to improve their happiness. Even after four years, men and women who lose their jobs are still as unhappy as when they first became unemployed … Broadly similar results have been found in Britain, the United States and Australia – as well as Russia, South Korea and Switzerland. The psychic effect of unemployment is large and there is little adaptation. Given the high degree of adaptation observed in response to many other life events, the lack of adaptation to losing a job is notable. In fact, when the passage of time is taken into account, the cumulative negative effect of long-term unemployment is greater than the long-term impact of becoming married, divorced, widowed or having children … Given this weight of evidence, the substantial negative impact of unemployment on wellbeing is widely regarded to be one of the largest and most robust findings to emerge from empirical happiness research.

Layard and De Neve ask:

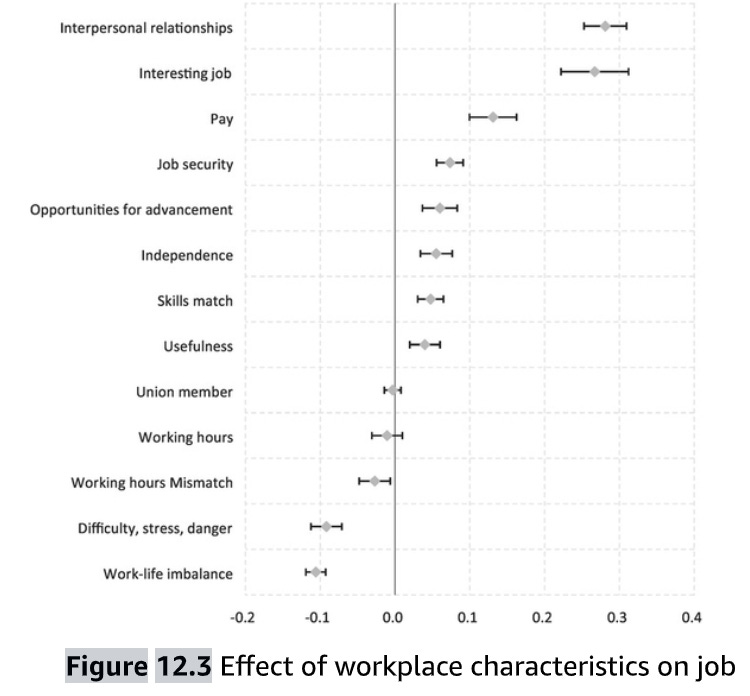

But why is unemployment so painful? One obvious answer might be the loss of income. But we have already taken this into account. And in fact we can easily compare the size of the non-pecuniary effects with those of the pecuniary effects. These comparisons have been done by a number of authors, all of whom found the non-pecuniary effects to be more than the pecuniary effects. For example, one widely cited analysis found them to be twice as large, and this is a typical estimate. So the costs of unemployment go far beyond the income loss … [M]odern theoretical understandings of employment continue to focus on three related channels through which work relates to wellbeing: (1) identity, (2) social network and (3) routine … At this point, readers may not be surprised to learn that the quality of social relationships at work is generally the most important single predictor of workplace wellbeing. In Figure 12.3, interpersonal relationships tops the list out of eleven drivers of job satisfaction. In Figure 12.3, the extent to which workers find their job interesting is the second most important predictor of job satisfaction.

Clifton, the head of the Gallup polling organization, adds that:

Gallup finds that only 20% of all people are thriving at work, while 62% are indifferent and 18% are miserable. And the misery that those 18% of workers feel consumes a massive part of their lives. The average person spends at least 81,396 hours of their life at work. That is the equivalent of more than 9 years.4 The only thing we spend more time doing is sleeping (about 33 years). If people truly spend that much time working, it’s no surprise that how a person feels at work hugely affects their overall life. If you are thriving at work, you rate your overall life significantly higher compared with someone who is miserable at work. But thriving at work not only improves how you see your life, you also live a better life. Gallup finds that if you are engaged and thriving at work, you experience far less stress, sadness, anger, pain, and worry every day compared with someone who hates their job. Thriving at work even enhances how much joy, laughter, respect, and intellectual stimulation you experience … The average full-time worker spends 41.36 hours per week working, according to the Gallup World Poll. Assuming people work 48 weeks per year, that’s 1,985.28 hours per year working. Life expectancy is 73 and, according to the OECD, people retire at about 63. If people begin working at 22, then the average person works 41 years. Forty-one years of work at 1,985.28 hours per year is 81,396 total hours. This estimate is conservative and may even be low; another estimate finds that people work over 115,000 hours in a lifetime.

Reductions in happiness, especially among men who are dropping out of the labor force, may be explained in part because dependency denies people the self-esteem and other well-being that comes with productive work.

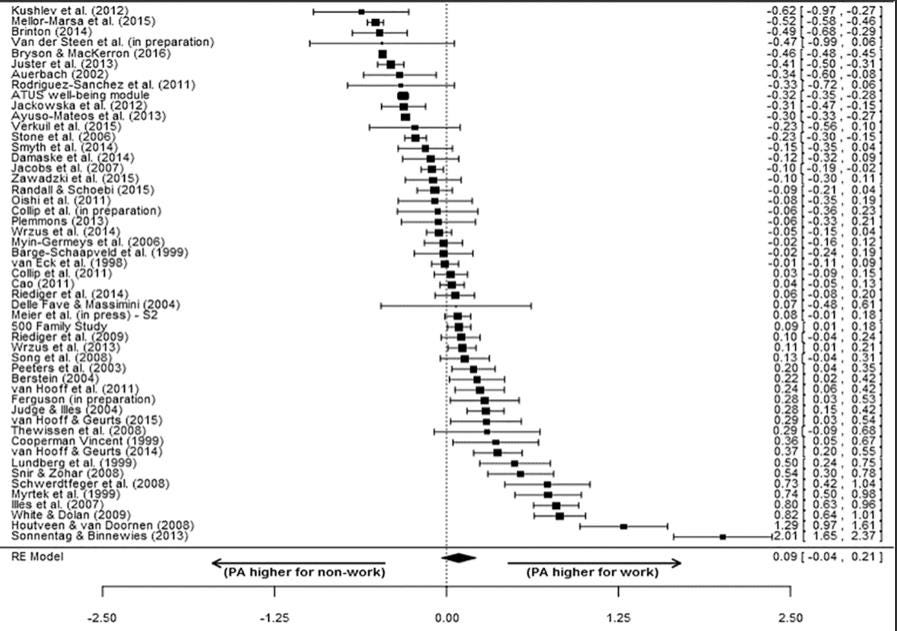

One meta-analysis found that research shows work is generally associated with positive affect when compared to non-work activities.

Regarding blue collar workers, as reported in the Wall Street Journal:

Conducted by the Harris Poll and commissioned by Express Employment Professionals, a staffing company, [a 2018] survey found that three of four blue-collar workers call their jobs “a good career path.” Four of five agree that “my job provides a good living to financially support my family.” Eighty-six percent say they are “satisfied” with their jobs, and 90% are “proud” of the work they do. It gets better. Seventy percent agree “the American Dream is alive for people like me,” and among those who are parents 88% agree with the statement that “my children will have a better future than I will.”

As Zachary Karabell writes in The Leading Indicators: A Short History of the Numbers That Rule Our World:

Jobs are particularly important because there is ample evidence—from surveys, at least—that increasing employment adds more to social contentment and stability than increasing income and output. That is true even for lower-paying jobs … [E]conomic policies that maximize employment serve collective happiness more than ones that maximize output … Happiness research has added a vital dimension to economics and led to a new set of statistics. Those have in no way supplanted the established indicators; happiness indices are still second-class citizens in statistics land.

Work’s relationship to a sense of broader meaning in life was recently explored by researchers who analyzed a historical dataset created during the 1930s when the FDR administration hired unemployed writers to record life stories of thousands of older Americans. In their paper “American Life Histories.” The stories include those from a broad cross-section of working America during the Great Depression. The researchers write:

Some of our findings demonstrate the veracity of folk wisdom – women care more about family and relationships than men. Others offer new insights: In addition to the importance of relationships and family, we find that the roles of work and of contributing to communities and society loom large. Men and women reminisce proudly about how they learned their trades, emphasizing their mastery of complex tasks. Such pride is by no means limited to the professionals in our dataset; they emphasize how their work allows them to leverage their skills like the librarian putting their love of learning to good use. Many respondents eagerly share their insights into mundane businesses, from the turpentine industry to bone-collecting after droughts. Work in these life narratives is not necessarily drudgery, reluctantly endured; in most cases, it is a source of pride, joy, social recognition, and standing in the community. In other words, many of the men and women in the American Life Histories corpus are homo faber (“man the maker” in Latin) – creatures that need to work, produce, and contribute to flourish.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll examine the effect income has on happiness, and the pernicious effects of status-consciousness.

Good work Paul. There is a human psychological need to work. Without it we grow psychologically unwell.