Continuing this essay series on happiness, primarily with reference to Wellbeing: Science and Policy, by Richard Layard and Jan-Emmanuel De Neve, and Blind Spot: The Global Rise of Unhappiness and How Leaders Missed It, by Jon Clifton, the head of the Gallup polling organization, this essay focuses on one of the five main elements of wellbeing: family and children, friends and community.

As Clifton writes regarding the happiness children bring to parents:

In the summer of 2012, Neli Esipova, then a Gallup World Poll regional director, found herself in Kyrgyzstan. She and a Gallup interviewer were conducting interviews in Bishkek, the country’s capital. They approached a randomly selected house and knocked on the door. A woman answered. They asked the woman if she would participate in our survey. She agreed and invited them into her home. Reading from a handheld device, Neli’s colleague began the interview, “On a scale of zero to 10, where zero is the worst possible life and 10 is the best possible life, where do you think you stood five years ago?” The woman looked at the interviewer and said, “Two.” The interviewer moved on to the next question: “Now, please rate your life on a scale of zero to 10. Where do you stand today?” Again, the woman said, “Two.” Then the interviewer asked, “Where do you think you will stand in the next five years?” The woman paused, thought for a second, and said, “10.” This jump is surprising. The woman just said her life was awful. A rating of two is terrible anywhere. Why would her life be a 10 in five years? At the end of the interview, Neli looked at the woman and said, “You said your life was a two five years ago, a two today, yet a 10 in five years — what changed?” The woman signaled to her belly and said, “I’m pregnant. Soon I’ll be giving birth to my son.”

Indeed, purpose and meaning are connected to what researchers call eudaimonic well-being, which is distinct from, and sometimes inversely related to, happiness (hedonic well-being). Eudaimonic well-being constitutes a deeper, more durable state, while hedonic well-being is superficial and transient. Parents with children report higher levels of happiness, positive emotion, and meaning in life. As the researchers conclude:

[P]arents (and especially fathers) report relatively higher levels of happiness, positive emotion, and meaning in life than do nonparents … [P]arents as a group reported being happier and more satisfied, and thinking more frequently about meaning in life than did their counterparts without children … Notably, across all three studies, all parents reported higher levels of meaning than did nonparents. In short, our results dovetail with emerging evolutionary perspectives that depict parenting as a fundamental human need.

Princeton and Stony Brook scientists surveyed 1.8 million Americans and found that while “parents and non-parents have similar levels of life satisfactions,” parents often had more emotionally intense lives in that they expressed higher highs and more joy than non-parents. General surveys show the same thing.

Most Americans mention “family” or “children” when asked what makes life meaningful.

Other studies show that the most important part of human well-being is family.

Interestingly, in a broader context, as one philosopher has written, if happiness is a good thing -- in fact, most public policy is premised in some way on reducing unhappiness on net -- then more people who can experience happiness on net must be a good thing: “Most people live lives that are, on net, happy. For them to never exist, then, would be to deny them that happiness. And because I think we have a moral duty to maximize the amount of happiness in the world, that means that we all have an obligation to make the world as populated as can be.” In that sense, people who raise generally happy and productive children are performing perhaps the greatest public service.

As Brad Wilcox of the American Enterprise Institute explains:

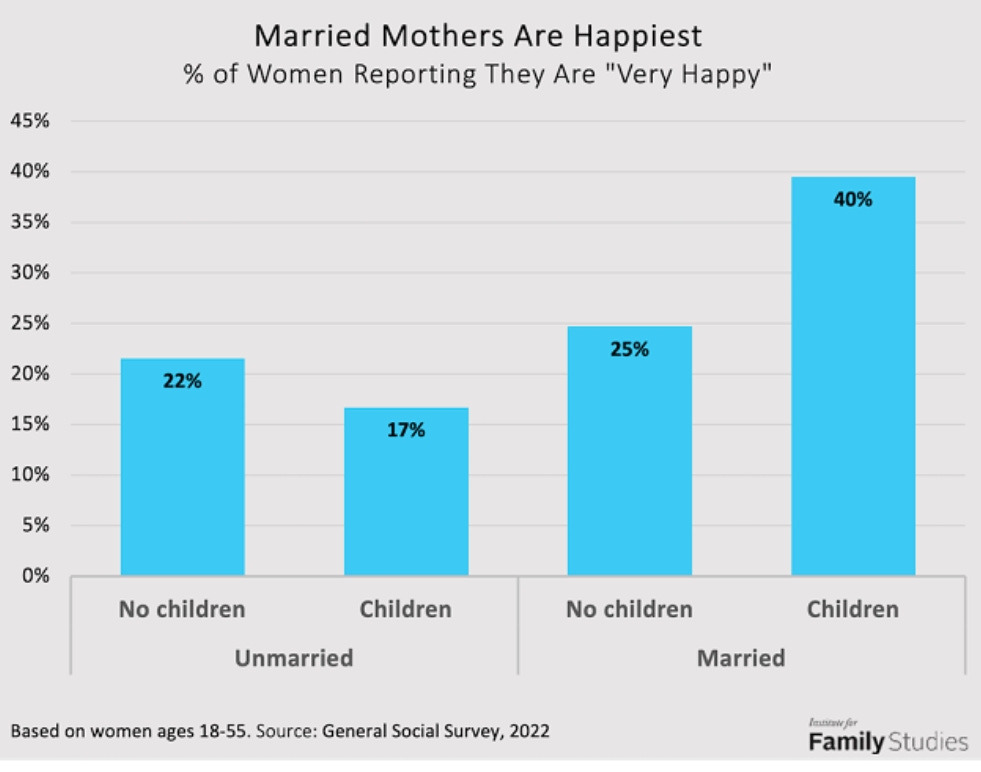

The 2022 edition of the General Social Survey (GSS)—the nation’s preeminent social barometer—reveals that marriage and family are strongly associated with happiness. The GSS shows that a combination of marriage and parenthood is linked to the biggest happiness dividends for women. Among married women with children between the ages of 18 and 55, 40% reported they are “very happy,” compared to 25% of married childless women, and just 22% of unmarried childless women.

Nevertheless, it is important to note that unmarried mothers are the least likely to be very happy: with just 17% of them indicating they are very happy. These results parallel findings from 2020 and 2021 during the pandemic that we reported last year in The Atlantic. In earlier surveys, we found that women who were married with children were generally the happiest and the least lonely. But what about men? Is the link between happiness, marriage, and parenthood similar for men? Indeed, the 2022 General Social Survey indicates that marriage is also linked to greater happiness for men ages 18-55. And here again, married fathers are happiest.

Specifically, 35% of married men ages 18-55 who have children report being “very happy,” followed by 30% of married men who do not have children. By contrast unmarried childless men, and especially unmarried fathers are the least happy—with less than 15% of these men saying they are “very happy.” In other words, married men (ages 18-55) in America are about twice as likely to be very happy, compared to their unmarried peers. These results parallel other recent research from the University of Chicago indicating that for both men and women, marriage is “the most important differentiator” of who is happy in America. Meanwhile, falling marriage rates are a chief reason why happiness has declined nationally, according to that same study. The research found an astounding 30-percentage-point happiness gap between married and unmarried Americans.

A 2025 anaylsis found a consistent historical happiness benefit associated with marriage:

Since 1972, the General Social Survey has periodically asked whether people are happy with Yes, Maybe or No type answers. Here I use a net "happiness" measure, which is percentage Yes less percentage No with Maybe treated as zero. Average happiness is around +20 on this scale for all respondents from 1972 to the last pre-pandemic survey (2018). However, there is a wide gap of around 30 points between married and unmarried respondents. This "marital premium" is this paper's subject. I describe how this premium varies across and within population groups. These include standard socio demographics (age, sex, race education, income) and more. I find little variety and thereby surface a notable regularity in US socio demography: there is a substantial marital premium for every group and subgroup I analyze, and this premium is usually close to the overall 30-point average. This holds not just for standard characteristics but also for those directly related to marriage like children and sex (and sex preference). I also find a "cohabitation premium", but it is much smaller (10 points) than the marital premium. The analysis is mainly visual, and there is inevitably some interesting variety across seventeen figures, such as a 5-point increase in recent years.

A review of happiness surveys also finds that happiness was associated most significantly with people who were married, conservative, and in the higher income quintiles:

Marital status is and has been a very important marker for happiness. A glance at Figure 3 shows this: the married population is over 30 points happier than the unmarried, and that number has hardly changed since the 1970s. It is the same (not shown) for men and women … It is about the same whether the unmarried state is due to divorce, separation, death of spouse or never having married … No subsequent population categorization will yield so large a difference in happiness across so many people (around one third of the sample is unmarried). The trendlessness in either category in Figure 3 contrasts to the downturn in overall happiness since 2000. The connection between these trends comes from recent decline in marriage … The recent decline in the married share of adults can explain (statistically) most of the recent decline in overall happiness.

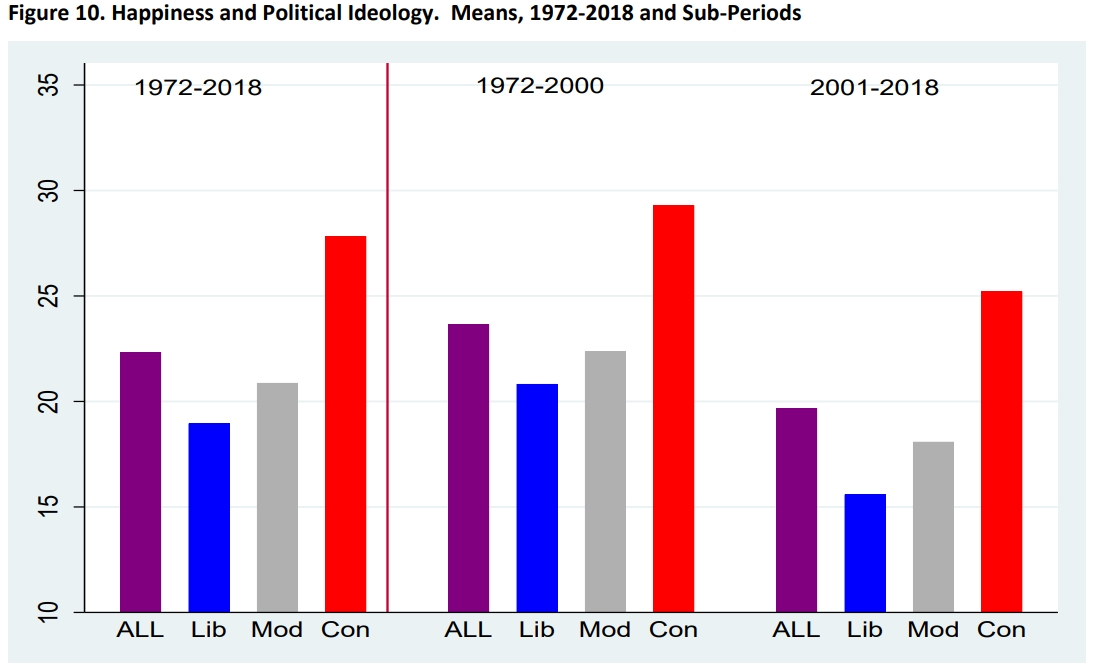

… Figure 10 has standard color coding – red for conservatives, liberals in blue and the whole sample in purple. Moderates are in gray. To capture any trends I show means for subperiods before and after 2000. The consistent pattern is increased happiness from left to right. Conservatives are around 9 points happier than liberals and 7 points happier than moderates overall and in each sub-period.

… In any snapshot of the population money matters a great deal. The middle of the richest half of the population is over 20 points happier than the middle of the bottom half. However, the Easterlin (1974) paradox lives on: the top income quintile is no happier today than in the 1970s in spite of substantial income growth.

Layard and De Neve also highlight some key findings on parenting and teachers, regarding the wellbeing-enhancing nature of certain aspects of the home and school environments:

[T]here are now a number of longitudinal studies, which follow the same person from the cradle into adult life, and most of our understanding of the impact of families and schooling comes from these surveys. In each of them, the wellbeing of the children is measured initially by questions to their parents and teachers and then (after about 10) to the children themselves as well. Here are some key findings. Every child needs unconditional love. The basic need is for a secure emotional tie to at least one specific person. This experience of “attachment” is the basis for an inner security that can last throughout life. A striking illustration of the importance of caring relationships comes from a tragic “natural experiment”. After the end of Communism, some Romanian orphans were randomly assigned to foster-care in Western families; the unlucky ones remained in the orphanage. On average, the children were 21 months old when they were assigned one way or the other, and they were assessed again at 4 ½ years of age. If they had been assigned for foster-care, the children’s mental and cognitive wellbeing at 4 ½ was over one half of a standard deviation higher than if they had stayed in the orphanage. And the younger the age at which the fostering began the better the outcome.

Regarding the act of parenting itself, Layard and De Neve emphasize the crucial role of firmness and discipline in any caring environment, including within the family and at school:

So the love of caregivers is essential. But so too is firmness – the ability to set boundaries. If combined with warmth, this is known as “authoritative” parenting, and it is the most widely recommended approach. In this approach, compliance with rules does not come from fear, but children learn to internalise the parent’s response and thereafter act to please their own “better selves”.

Regarding discipline at school, Layard and De Never describe the “Good Behavior Game” experiment that was conducted in schools in a deprived area of Baltimore:

In the treatment group, each first-year primary class is divided into three teams, and each team is scored according to the number of times a member of the team breaks a rule. If the team has fewer than five infringements, a reward goes to all members of the team. Children who played (or did not play) the game were followed up to ages 19–21, and those in the treatment group used fewer drugs, less alcohol and less tobacco, and fewer had anti-social personality disorder.

The relationship between the parents is also important:

So for a child the relationship to her parents is crucial. But so is the relationship between the parents themselves. At present, 50% of 16-year-olds are in separated families in the United States, and in Britain it is over 40%. How much does this matter? The literature on child development is large. However, most of the main findings can be illustrated from within one study, which makes the findings on different influences easier to compare. This is the famous ALSPAC survey of all the children born in or around Bristol, England in 1991/2. Table 9.1 shows how their parents affected the wellbeing of their children – and also their behaviour and their academic performance (all measured at age 16).

As the table shows, family conflict is bad for all three of these outcomes [wellbeing, behavior, and academics]. And, incidentally, for any given level of family conflict, a break-up of the family causes no additional damage, except to academic performance. But ongoing conflict between the parents after they break up increases the risk that the children will become depressed or aggressive. Closely related to family conflict is the mental health of the parents. In the Bristol study, the single most important family variable predicting a child’s wellbeing at 16 was the mental health of the mother. The father’s mental health also mattered but less so – probably because the mother is still, generally, the primary care giver.

Regarding schooling, Layard and De Neve write:

Some negative findings are fairly well established: Smaller class sizes have no well-established advantages, in terms of their impact on wellbeing (or on intellectual development). Larger schools have no well-established advantages in terms of wellbeing … In almost every country, school discipline is a problem, at least in some classrooms.

(The problem of lack of discipline in classrooms generally was explored in a previous essay.)

Regarding the role of trust in society and its effect on happiness, Layard and De Neve write:

We can also examine the effect of trust at the individual level. In one survey, people were asked whether they would expect a lost wallet containing $200 to be returned. Those who said “Very likely” were experiencing (other things equal) an extra one point of wellbeing (out of 10) compared with those who said “Very unlikely”.

As Clifton writes:

[H]ow much does an environment of trust affect how your life is going? The short answer is — a lot. According to the WHR [World Happiness Report], people who trust their neighbors and who trust strangers are far more likely to rate their lives better. Trust is even more influential than doubling your income and the net loss of being unemployed. Additionally, research finds that communities with high trust are more resilient during severe economic contractions and natural disasters.

And as Layard and De Neve explain, religiosity is also associated with wellbeing (as was also explored in a previous essay):

But what of the specific effect of religion? … [A]llowing for other factors, people in more religious US states are on average more satisfied with life. And so are more religious people … [M]eta-analysis concludes that greater religiosity is mildly associated with fewer depressive symptoms and 75% of studies find at least some positive effect of religion on wellbeing … [R]eligion can reduce the wellbeing consequences of stressful events, via its stress-buffering role. There is some longitudinal evidence suggesting that it is the friendship and social support that result from religious attendance that do most to enhance wellbeing.

Geography is important to happiness as well. People living in rural area are also generally happier than people living in urban areas.

Researchers who studied the incidence of “psychopathy” in the U.S. -- defined in terms of “low extraversion, very low agreeableness and conscientiousness, very high neuroticism, and moderately high openness” – found that:

Areas of the United States that are measured to be most psychopathic are those in the Northeast and other similarly populated regions. The least psychopathic are predominantly rural areas. The District of Columbia is measured to be far more psychopathic than any individual state in the country, a fact that can be readily explained either by its very high population density or by the type of person who may be drawn to a literal seat of power.

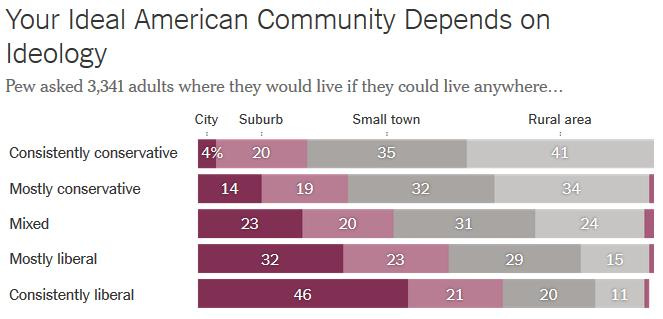

Dovetailing with a previous essay noting the greater general happiness among those who are ideologically conservative, conservatives much prefer to live in small towns and rural areas, whereas liberals much prefer to live in big cities.

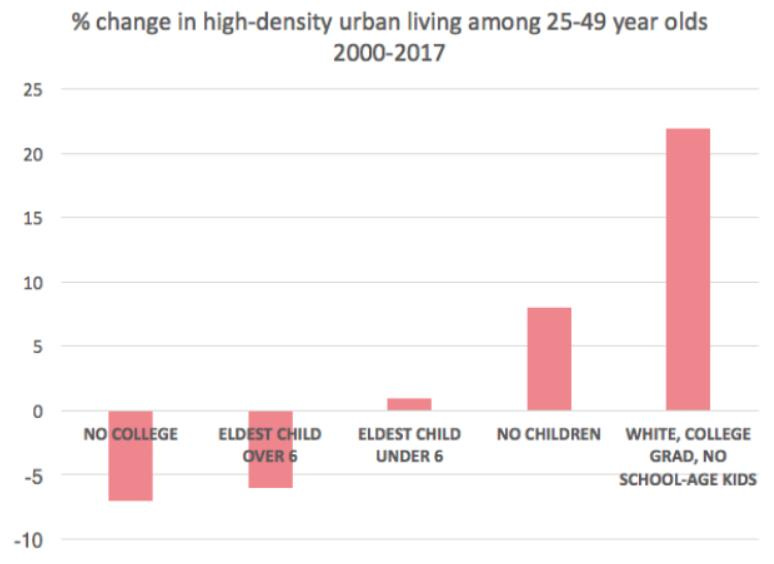

Also dovetailing with the previous essay describing how people with children tend to be happier than those without, as has been reported: “In high-density cities like San Francisco, Seattle, and Washington, D.C., no group is growing faster than rich college-educated whites without children, according to Census analysis by the economist Jed Kolko. By contrast, families with children older than 6 are in outright decline in these places. In the biggest picture, it turns out that America’s urban rebirth is missing a key element: births.”

In the next essay in this series, we’ll explore how employment affects happiness and wellbeing.