Happiness – Part 2

An introduction to happiness studies.

In the following essays in this series on happiness, we’ll focus on several main elements of happiness, namely physical and mental health, family and children, occupation and career, income and wealth, and friends, community, and culture, using two more science-oriented books: Wellbeing: Science and Policy, by Richard Layard and Jan-Emmanuel De Neve, and Blind Spot: The Global Rise of Unhappiness and How Leaders Missed It, by Jon Clifton, the head of the Gallup polling organization, among many other sources.

Layard and De Neve introduce the complex subject of wellbeing as follows:

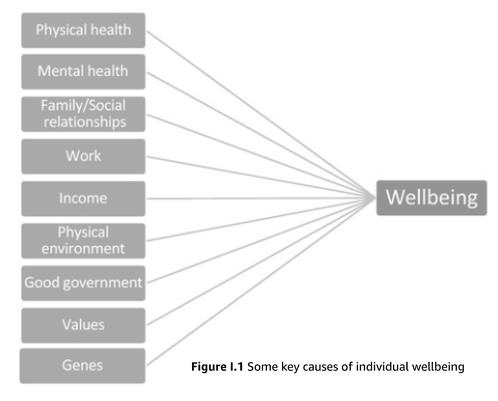

By wellbeing we mean how you feel about your life, how satisfied you are. Wellbeing, this book argues, is the overarching good and other goods (like health, family and friends, income and so on) are good because of how they contribute to our wellbeing. This idea is basic to the subject. It is illustrated in Figure I.1, which shows some of the more obvious causes of wellbeing. So the key to a happier society is to understand how these various factors affect our wellbeing and how they can be altered for the better. Fortunately we have a whole new science to help us do that – the science of wellbeing.

As Layard and De Neve write:

In the eighteenth-century Anglo-Scottish Enlightenment, the central concept was that we judge a society by the happiness of the people. But, unfortunately, there was at the time no method of measuring wellbeing. So income became the measure of a successful society, and GDP per head became the goal. But things are different now. We are now able to measure wellbeing, and policy-makers around the world are turning towards measures of success that go ‘beyond GDP’. This shift is really important because, as we shall see, income explains only a small fraction of the variance of wellbeing in any country.

This discussion reminded me of some passages in a book I read a while back in Zachary Karabell’s The Leading Indicators: A Short History of the Numbers That Rule Our World, in which he recounts an interesting speech Robert Kennedy made back in 1968:

New York senator Robert Kennedy, younger brother of a slain president, former attorney general, onetime Cold War crusader turned born-again reformer, called on Americans to rethink their metrics of success and demanded a new way to measure the collective good. In a campaign speech at the University of Kansas in March, the newly declared candidate for president was unsparing in his critique: “Yet the gross national product does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education, or the joy of their play. It does not include the beauty of our poetry or the strength of our marriages; the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials. It measures neither our wit nor our courage; neither our wisdom nor our learning; neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country. It measures everything, in short, except that which makes life worthwhile. And it tells us everything about America except why we are proud that we are Americans.”

In fact, there have been a few, quixotic, attempts to realize Robert Kennedy’s aspiration. For example, as Karabell writes, King Jigme Singye Wanchuck, the inheritor of the Dragon Throne of Bhutan:

There is no evidence that the young king was aware of Robert Kennedy’s searing 1968 critique of gross national product. He would have been barely twelve years old when Kennedy delivered that speech in Kansas. But somehow, one of the first decisions made by this new king of Bhutan was to replace GNP with something else: happiness. From then on, the goal for Bhutan was not material prosperity but collective well-being. Bhutan, the king believed, would be a successful society only if most of its people deemed themselves happy … The first recorded legal code of Bhutan dates from the eighteenth century. Formulated by a ruler who was also a Buddhist Rinpoche, or high-ranking monk, the code stated, “If the government cannot create happiness for its people, there is no purpose for the government to exist.” It was one thing for the king to pronounce that Bhutan would use a different measuring stick; it was another thing to create the measures. That process is still not complete … Stemming from centuries of Buddhist teachings and an isolated culture steeped in that legacy, the methodology of the gross national happiness index bears more resemblance to New Age teachings than it does to the statistical mantras of the Bureau of Economic Analysis … While every country in the world except for Bhutan now uses GDP as the primary proxy for economic success [,] Bhutan was the first—and, to date, the only—sovereign nation that has rejected the core metric of modern economies.

In 2007, the President of France also explored the possibility of a standard for Gross National Happiness:

It is almost impossible to imagine a public figure in the Western world using this language. And yet, in the past few years, the underlying ideas have crept into the once-unassailable halls of Western culture and pushed themselves to the center. It’s as if there are two parallel tracks: one continues and deepens the work of Ethelbert Stewart and the twentieth-century children of Keynes and Kuznets, and seeks precise calculations of the components of an iPhone or the definition of employment; the other looks at society as a holistic mix of the spiritual, material, collective, and personal. The chairman of the Federal Reserve and government economists might never speak in such terms explicitly, and would likely react with a mixture of perplexity and derision if asked to revise current metrics along Bhutanese lines. Yet that is precisely what Nicolas Sarkozy did as president of France between 2007 and 2012. Sarkozy struck no one as a man of contemplation. If anything, he was described by friends and adversaries alike as a whirlwind of id determined to haul the French economy into the twenty-first century by making it more ruthless and competitive. Fair enough. Yet in his few years as president, he convened a high-level commission with the explicit mandate to rethink GDP as the measure of all measures and replace it with something akin to what that sixteen-year-old Bhutanese king had set in motion in 1972. “I hold a firm belief,” Sarkozy explained, “[that] we will not change our behavior unless we change the ways we measure our economic performance ... Our statistics and accounts reflect our aspirations, the values that we assign things. They are inseparable from our vision of the world and the economy ... Treating these as objective data, as if they are external to us, beyond question or dispute, is undoubtedly reassuring and comfortable, but it’s dangerous . . . That is how we begin to create a gulf of incomprehension between the expert certain in his knowledge and the citizen whose experience of life is completely out of synch with the story told by the data.” And in that spirit and with that conviction, in 2008 Sarkozy asked Nobel Prize–winning economists Joseph Stiglitz and Amartya Sen, along with French-born economist Jean-Paul Fitoussi, to chair a commission to revamp and potentially replace GDP … Many societies, the United States included, describe happiness as a core social value. The American Declaration of Independence famously defended the right of citizens to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” You might ask why even bother. If happiness, contentment, and well- being are all subjective states, then coming up with a number to represent them would seem a fool’s errand. If you create a 1 to 10 scale and ask people to state their happiness number, one person’s 6 could be another person’s 9. Traditional economists take as a given that people can lie to themselves and others about what they feel. But they cannot hide their economic actions, and actions don’t lie. That means you can measure actions and their real- world consequences with some degree of certainty, but not well- being. At some point in the past thirty years, however, scholars interested in human behavior and economics began to craft ways to measure and quantify subjective experiences. Very much in the spirit of George Katona, Daniel Kahneman (who would earn a Nobel Prize for his work in 2002), Edward Diener, Alan Krueger (who later became President Obama’s chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers), and William Nordhaus all began to investigate how best to come up with standardized measures of well-being. Given their training as economists and social scientists, they sought to match behavior and observations with numbers and formulas. They sought, in short, to create metrics for happiness that were equivalent to the statistics for inflation, employment, and GDP. They did so because they believed that GDP was both mismeasuring society and creating incentives that might not lead to a better world. Even a government uninterested in increasing the well-being of citizens would be troubled by the thought that economic indicators were hampering efforts to become stronger and more competitive in a competitive world. As Stiglitz, Sen, and Fitoussi explained in unveiling the results of the work commissioned by Sarkozy, “In an increasingly performance-oriented society, metrics matter. What we measure affects what we do. If we have the wrong metrics, we will strive for the wrong things. In the quest to increase GDP, we may end with a society in which the citizens are worse off.”

Of course, aggregate national measures aside, as Layard and De Neve remind us, the aspect of happiness over which we have the most control is our own reactions to events:

[T]here is also a huge role for us as individuals: in determining how our experience of life affects our own feelings. It matters how we think. For our thoughts affect our feelings. The reverse is also true of course – our feelings affect our thoughts. But the way to break into this cycle is by managing our thoughts. The importance of ‘mind-training’ was stressed in many ancient forms of wisdom (such as Buddhism, Stoicism and many religious traditions). But in the West, its importance has been re-established in the last fifty years and proved by state-of-the-art randomised experiments … We influence our own wellbeing in two key ways: By our behaviour, we significantly influence the situations we experience and the behaviour of others towards us. By our thoughts, we influence how these experiences affect us – both through our attitudes and how we think about our life. From this analysis it is clear that our wellbeing does not only depend on our social environment. It also depends on what we bring to the table, in particular our behaviour, our thinking and our genes.

Regarding the influence of genes, over which we have less control, Layard and De Neve write:

An important part of who we are is determined by our genes. Evidence of their importance comes from two sources. The first are twin studies. These show that identical twins (who have the same genes) are much more similar to each other than non-identical twins are. For example, the correlation in wellbeing between identical twins is double what it is between non-identical twins. Any parent who has produced more than one child can see how children differ, even if they are brought up in exactly the same way. Our genes matter and now we are beginning to be able to track down which specific genes are important for wellbeing … The one part of our body that never changes is our genes. They were determined at the moment of our conception and, apart from mutations, we keep the same genes throughout our life. The same genes are present in the nucleus of nearly every cell in our body. It is the continuity in our genes that explains much of the continuity in our personality, our appearance and our behaviour over our life … To see that genes matter we have only to look at the following data on Norwegian middle-aged, same-sex twins (see Table 5.3). Some of the twins are identical: both come from the same egg. They therefore have the same genes and look more-or-less identical. The other sets of twins are non-identical: each twin comes from a separate egg. So half her genes are the same as her co-twin’s but half are different (just as is the case with any other pair of siblings). And what a difference that makes! As Table 5.3 shows, if the twins are identical, their life satisfaction is fairly similar (with a correlation across the 2 twins of 0.31). But if the twins are non-identical, their enjoyment of life is much less similar (with an across-twin correlation of only 0.15).

When studying wellbeing, a key source of evidence has been the Minnesota Twin Registry, which includes twins who were raised together and twins who were raised apart (as adoptees). The study showed that identical twins raised apart were much more similar in wellbeing (r = 0.48) than non-identical twins brought up by their biological parents (r = 0.23). This again underscores the importance of genetic factors … So the genes really matter. But so does the environment that we experience. In fact, the environment is generally more important. Even with the most heritable mental trait that we know of (bipolar disorder) only just over a half of the co-twins of bipolar people also have the condition. And for most conditions it is much less. Moreover, genes do not operate on their own, with the environment just adding further effects. Rather, the genes and the environment interact, with the genes influencing the effect that the environment has on us and vice versa. This we can see clearly in the following study of the impact of negative life events on a sample of twins in Virginia. Negative life events included the death of a loved one, divorce/separation and assault. And the issue was how frequently did those people who had a negative event experience a major depression in the subsequent month? Therefore, for each individual the study measured (i) what negative events they experienced, (ii) whether major depression followed within a month and (iii) the mental health and relatedness of the individual’s co-twin. As Table 5.4 shows, a person was more likely to experience a major depression if their co-twin was depressed (especially an identical twin who was). And they were less likely to be depressed if their co-twin was non-depressed (especially if it was an identical twin). This is a clear case where people have bad experiences but the effect depends also on how far their genes predispose them to depression.

Evidence of such interaction is ubiquitous. For example, in one study of adopted children anti-social behaviour was more common in adolescents if their adoptive parents were anti-social. But the effect was greater still when the biological parents were also anti-social … The conclusion is that there is no single gene for happiness, or even a small number of genes. Instead, thousands or more genes are involved, interacting in complicated ways with each other and with the environment. Taken together, these genes predispose people to more or less happy lives.

As Clifton adds in his book Blind Spot:

Genetics is another major factor. Research (including several studies of twins) finds that genetics plays a significant role in someone’s wellbeing. Studies estimate that 30% to 50% of someone’s emotional state was built in the day they were born. This is often called the happiness set point: No matter what happens to you in your life, you revert to your genetically determined set point. For example, let’s say you rate your life a 7 today; tomorrow, you move into a big new house. After the move, you rate your life a 10. The happiness set point theory suggests that the emotional bounce you got from moving into the new house will eventually wear off. In a year or two, your life rating will revert to a 7 (your set point) — your rating before moving into the new house. The same is true if something awful happens, such as getting into an accident. You were a 7 before the accident, but after the accident, you rate your life a 2. Despite the trauma, later in life you revert to a 7. However, more recent research finds that people often do not have a complete rebound from a traumatic experience — if something awful happens, you may still improve, but not to where you were originally. A theory similar to the happiness set point is the “hedonic treadmill,” which says that by nature, people are always running toward a better life, but no matter what happens, their happiness always remains in the same place.

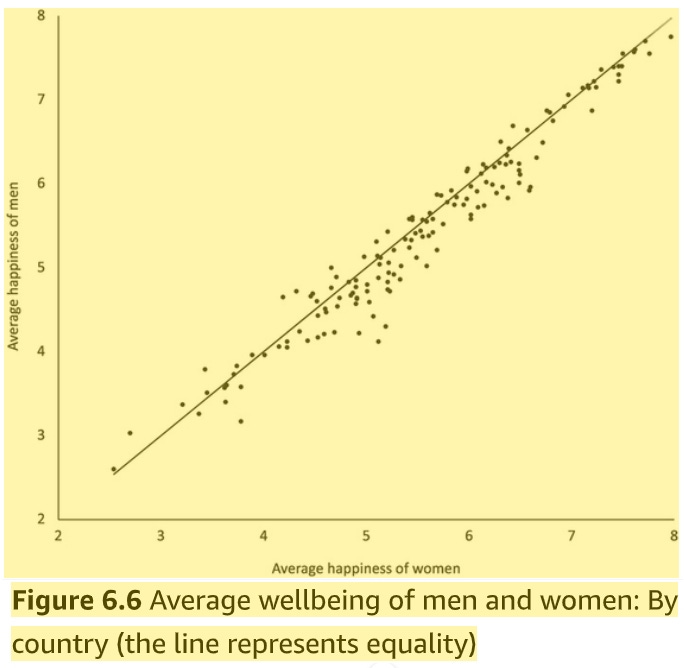

While genes have an impact on happiness, interestingly, there do not seem to be any significant sex differences in happiness worldwide. As Layard and De Neve write:

Remarkably, the distribution of wellbeing in the world is almost identical for men and women. Women are on average slightly happier than men but the difference is only 0.09 points (out of 10) – one fiftieth of the difference between the happiest and least happy country. Moreover, in almost every country the average wellbeing of men and women is nearly the same, even though wellbeing differs so hugely between countries (see Figure 6.6 [in which each dot represents a different country surveyed]).

And sadly, both men and women in the United States seem to have become less happy since the 1970’s:

In the United States since the 1970s, both men and women have become less happy, and this has been especially true of white women … In an analysis for Britain, Australia and the United States, mental health problems accounted for more of the misery than any other factor. In Britain and Australia, this was followed by physical illness, and in the United States by low income.

Clifton explores the rise of unhappiness in the United States over the past several decades. He writes:

Every year, Gallup interviews people in over 140 countries to ask them how their lives are going. The following conversation — translated into English — is an exchange between a Vietnamese interviewer and a female shoe factory worker in Ho Chi Minh City.

Interviewer: Did you feel well-rested yesterday?

Woman: No. I am working 12 hours a day at the factory, but I still don’t have enough money.

Interviewer: Were you treated with respect all day yesterday?

Woman: Don’t know. I will get into fights if I don’t finish my target.

Interviewer: Did you smile and laugh a lot all day yesterday?

Woman: [Silence] Interviewer: Sis, are you still there?

Woman: [Struggles to answer]

Interviewer: You can talk to me if you have anything to share.

Woman: [Crying] No one ever asks me whether I’m happy or not, whether I’m well or sick.

This worker is struggling. You can feel her unhappiness. But how many people in the world feel just like her? In other words, how much unhappiness is there in the world?

Clifton, too, discusses the nuances of trying to measure happiness among different people in different life circumstances:

[L]ook at two middle-aged Americans, one with young children and one without. How do they see life, and how do they experience life? Both rate their lives similarly, but they experience life differently. The person with young children experiences more positive and negative emotions. Meaning, the person with children is more likely to experience stress, sadness, and anger; they are also more likely to experience joy and laughter.

As Clifton explains, another nuance of trying to measure happiness involves different cultural understandings of the words used in survey questions. For example:

You can ask anything you want and get a response, but it does not mean you are measuring the same thing in every country. Another example is the word “risk.” As part of the Lloyd’s Register Foundation World Risk Poll, we asked, “When you hear the word ‘risk,’ do you think more about opportunity or danger?” Globally, 60% think danger, and 21% think opportunity (8% say both and 11% say neither, don’t know, or refused to answer). But then look at the results by the language the survey was administered in. If you ask native Spanish speakers about risk (riesgo), 85% hear the word and think danger (12% think opportunity). If you ask someone whose native language is English, 67% who hear the word think danger, and 27% think opportunity. The differences in perceived risk may not even be a linguistic issue — they might be more of a cultural influence.

Clifton points out that humans also have certain psychological tendencies that tilt their perceptions of their own happiness:

People are loss averse. Or, as Los Angeles Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully used to say, “Losing feels worse than winning feels good.” This is how loss aversion works: If you lose $20 and find $20 in the same day, economically, you are whole. But emotionally, you are not. Losing $20 causes pain that finding $20 does not make up for. Loss aversion affects entire countries the same way it affects individuals. Oxford economist Jan-Emmanuel De Neve and his colleagues looked at how life evaluation fluctuates based on economic expansions and contractions. An economic contraction causes life ratings to drop far more than an economic boom causes life ratings to increase. According to the authors, “… life satisfaction of individuals is between two and eight times more sensitive to negative growth as compared to positive economic growth. People do not psychologically benefit from expansions nearly as much as they suffer from recessions.” Their recommendation? Policymakers should do everything they can to create slow, consistent growth.

Although measuring happiness is difficult, in the end surveys on happiness are meaningful, if only because people know themselves best. As Clifton writes:

On a fall day in 2009, my morning started in a conference room in a midtown Manhattan office. You could see the famous Radio City Music Hall sign from the 23rd-floor window. I was there to meet with a foundation Gallup was working with to study hunger in Africa. The foundation had retained a university professor to advise us on the study, and he was there as well. Everything went as planned and nothing about the meeting was particularly noteworthy, except for one thing — an exchange between the professor and me. For months, I had encouraged the foundation to include questions about wellbeing in their hunger survey. I brought it up again in this meeting, hoping they would finally use these items. The professor — who had never liked the idea — reiterated that they did not want to ask wellbeing questions in the survey. I still could not figure out why, so I asked him. He didn’t think twice about the question and replied, “We want to make sure that Africans don’t say they are happier than they really are.” There it was. The professor was concerned that Africans could not accurately describe how their lives are going. Except Africans — and all people — do know how their lives are going. And they can accurately describe their lives to anyone who asks them. This is why we use surveys to measure wellbeing — to understand how people’s lives are going, we need to hear from people themselves.

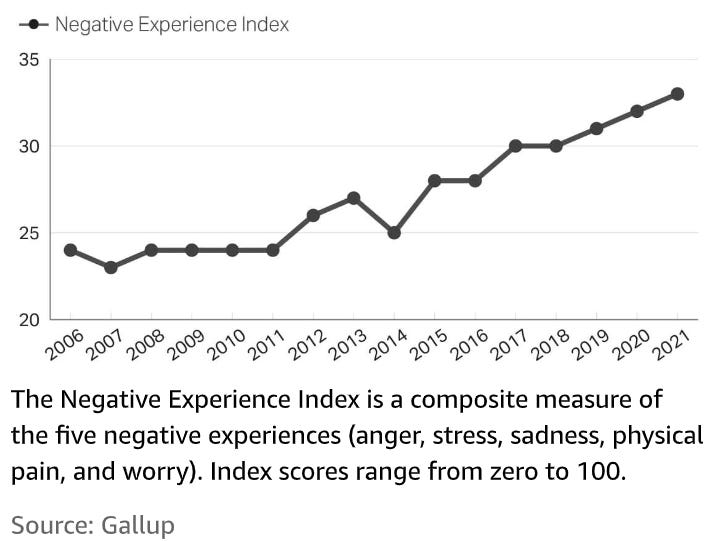

And Gallup’s worldwide polling indicates a general trend in the direction of unhappiness:

All five negative emotions have increased since we began tracking them. And Gallup’s Negative Experience Index is up 10 points since 2007, with most of the increase taking place since 2014. Between 2019 and 2021, only 17 out of 146 countries were home to a majority of people who were thriving, according to their own life evaluations. During that same time period, only two countries had a majority of people who were suffering: Afghanistan and Lebanon. The 2021 measurement alone was the highest suffering rate Gallup has ever seen in the history of our database. (Ninety-four percent of Afghans were suffering at the time of the survey, which took place from August to September and coincided with the U.S. troop withdrawal.)

Clifton describes the five elements that contribute to a thriving life, elements that will help organize future essays in this series:

While there are many different things that contribute to a great life, Gallup finds that there are five aspects all people have in common: their work, finances, physical health, communities, and relationships with family and friends. If you are excelling in each of these elements of wellbeing, it is highly unusual for you not to be thriving in life … Wellbeing research by other organizations has produced similar results. A 2021 study by the Pew Research Center spanning 17 countries found that the top answers people gave when asked what makes life meaningful were: family and children, occupation and career, material wellbeing (wealth), friends and community, and physical and mental health … Pablo Diego-Rosell, my colleague in Spain, looked at how much the five elements of wellbeing predict a great life. He found that they predict at least 50% of a great life globally.

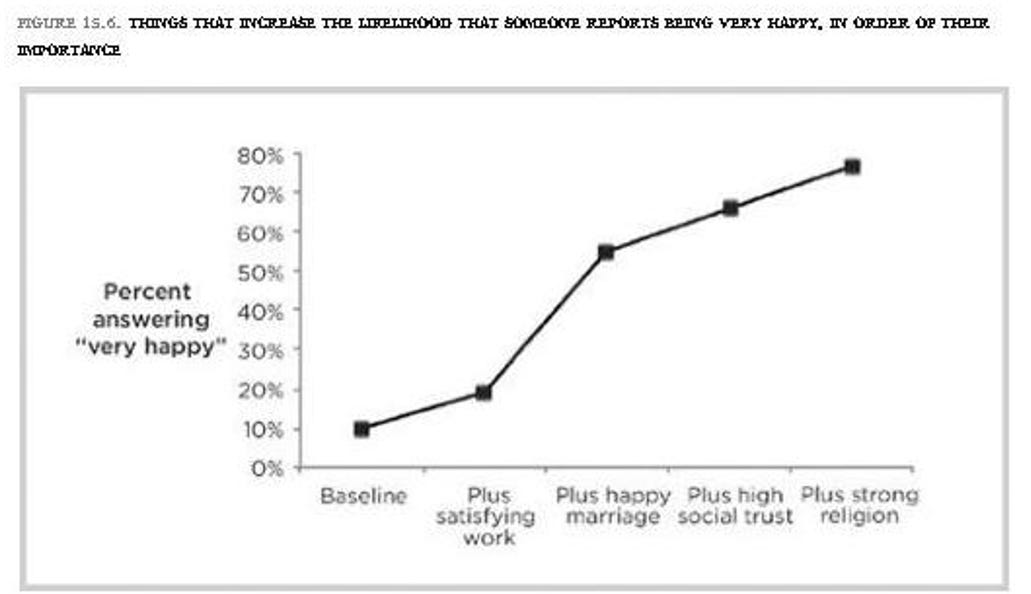

Charles Murray also finds much the same, noting in his book Coming Apart that people are much more likely to report that their life is “very happy” when they report having a satisfying job, a happy marriage, high trust in others, and strong religious involvement:

At baseline—unmarried, dissatisfied with one’s work, professing no religion, and with very low social trust—the probability that a white person aged 30–49 responded “very happy” to the question about his life in general was only 10 percent. Having either a very satisfying job or a very happy marriage raised that percentage by almost equal amounts, to about 19 percent, with the effect of a very satisfying job being fractionally greater. Then came the big interaction effect: having a very satisfying job and a very happy marriage jumped the probability to 55 percent. Having high social trust pushed the percentage to 69 percent, and adding strong religious involvement raised the probability to 76 percent.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll examine the effect of physical and mental health on happiness.