Continuing this essay series on Milton Friedman’s classic book, Free to Choose, this essay focuses on his discussion of the dangers posed to personal freedom in America today by the growth of government over the last century.

Friedman describes the historical origins of what came to be called the “New Deal”:

The presidential election of 1932 was a political watershed for the United States. Franklin Delano Roosevelt [the newly elected Democratic president] devised measures to be taken after his inauguration that grew into the “New Deal” FDR had pledged to the American people in accepting the Democratic nomination for President. The election was also a watershed in a more important sense; it marked a major change in both the public’s perception of the role of government and the actual role assigned to government. One simple set of statistics suggests the magnitude of the change. From the founding of the Republic to 1929, spending by governments at all levels, federal, state, and local, never exceeded 12 percent of the national income except in time of major war, and two-thirds of that was state and local spending. Federal spending typically amounted to 3 percent or less of the national income. Since 1933 government spending has never been less than 20 percent of national income and is now over 40 percent, and two-thirds of that is spending by the federal government … [H]e immediately launched a frenetic program of legislative measures—the “hundred days” of a special congressional session. World War II interrupted the New Deal, while at the same time strengthening greatly its foundations. The war brought massive government budgets and unprecedented control by government over the details of economic life: fixing of prices and wages by edict, rationing of consumer goods, prohibition of the production of some civilian goods, allocation of raw materials and finished products, control of imports and exports.

The increase in the size of government occurred in America not as a result of wholesale central planning, but as a result of ever-expanding welfare benefits:

Government has expanded greatly. However, that expansion has not taken the form of detailed central economic planning accompanied by ever widening nationalization of industry, finance, and commerce, as so many of us feared it would. Experience put an end to detailed economic planning, partly because it was not successful in achieving the announced objectives, but also because it conflicted with freedom. The failure of planning and nationalization has not eliminated pressure for an ever bigger government. It has simply altered its direction. The expansion of government now takes the form of welfare programs and of regulatory activities … In the welfare area the change of direction has led to an explosion in recent decades, especially after President Lyndon Johnson declared a “War on Poverty” in 1964. New Deal programs of Social Security, unemployment insurance, and direct relief were all expanded to cover new groups; payments were increased; and Medicare, Medicaid, food stamps, and numerous other programs were added. Public housing and urban renewal programs were enlarged. By now there are literally hundreds of government welfare and income transfer programs. The Department of Health, Education and Welfare, established in 1953 to consolidate the scattered welfare programs, began with a budget of $ 2 billion, less than 5 percent of expenditures on national defense. Twenty- five years later, in 1978, its budget was $ 160 billion, one and a half times as much as total spending on the army, the navy, and the air force. It had the third largest budget in the world, exceeded only by the entire budget of the U.S. government and of the Soviet Union. The department supervised a huge empire, penetrating every corner of the nation. More than one out of every 100 persons employed in this country worked in the HEW empire, either directly for the department or in programs for which HEW had responsibility but which were administered by state or local government units. All of us were affected by its activities. (In late 1979, HEW was subdivided by the creation of a separate Department of Education.) No one can dispute two superficially contradictory phenomena: widespread dissatisfaction with the results of this explosion in welfare activities; continued pressure for further expansion. The objectives have all been noble; the results, disappointing. Public housing and urban renewal programs have subtracted from rather than added to the housing available to the poor. Public assistance rolls mount despite growing employment. By general agreement, the welfare program is a “mess” saturated with fraud and corruption. As government has paid a larger share of the nation’s medical bills, both patients and physicians complain of rocketing costs and of the increasing impersonality of medicine. In education, student performance has dropped as federal intervention has expanded.

Friedman describes how the growing ranks of bureaucrats hired to administer welfare programs came to be some of the biggest supporters of those programs:

Despite the failure of these programs, the pressure to expand them grows … Special interests that benefit from specific programs press for their expansion—foremost among them the massive bureaucracy spawned by the programs … The first modern state to introduce on a fairly large scale the kind of welfare measures that have become popular in most societies today was the newly created German empire under the leadership of the “Iron Chancellor,” Otto von Bismarck. In the early 1880s he introduced a comprehensive scheme of social security, offering the worker insurance against accident, sickness, and old age. His motives were a complex mixture of paternalistic concern for the lower classes and shrewd politics. His measures served to undermine the political appeal of the newly emerging Social Democrats. It may seem paradoxical that an essentially autocratic and aristocratic state such as pre-World War I Germany—in today’s jargon, a right-wing dictatorship—should have led the way in introducing measures that are generally linked to socialism and the Left. But there is no paradox—even putting to one side Bismarck’s political motives. Believers in aristocracy and socialism share a faith in centralized rule, in rule by command rather than by voluntary cooperation. Both proclaim, no doubt sincerely, that they wish to promote the well-being of the “general public,” that they know what is in the “public interest” and how to attain it better than the ordinary person. Both, therefore, profess a paternalistic philosophy. And both end up, if they attain power, promoting the interests of their own class in the name of the “general welfare.” The defects of our present system of welfare have become widely recognized. The relief rolls grow despite growing affluence. A vast bureaucracy is largely devoted to shuffling papers rather than to serving people. Once people get on relief, it is hard to get off. The country is increasingly divided into two classes of citizens, one receiving relief and the other paying for it.

Friedman then, as of 1979, measures the failure of these government programs:

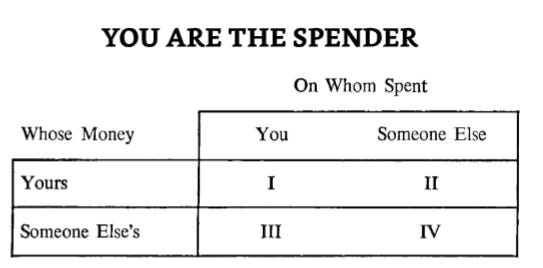

The so-called poverty level for 1978, as estimated by the Census, was close to $7,000 for a nonfarm family of four, and about 25 million persons were said to be members of families below the poverty level. That is a gross overestimate because it classifies families solely by money income, neglecting entirely any income in kind—from an owned home, a garden, food stamps, Medicaid, public housing. Several studies suggest that allowing for these omissions would cut the Census estimates by one-half or three-quarters.16 But even if you use the Census estimates, they imply that expenditures on welfare programs amounted to about $3,500 per person below the poverty level, or about $14,000 per family of four—roughly twice the poverty level itself. If these funds were all going to the “poor,” there would be no poor left—they would be among the comfortably well-off, at least. Clearly, this money is not going primarily to the poor. Some is siphoned off by administrative expenditures, supporting a massive bureaucracy at attractive pay scales. Why have all these programs been so disappointing? Their objectives were surely humanitarian and noble. Why have they not been achieved? At the dawn of the new era all seemed well. The people to be benefited were few; the taxpayers available to finance them, many—so each was paying a small sum that provided significant benefits to a few in need. As welfare programs expanded, the numbers changed. Today all of us are paying out of one pocket to put money—or something money could buy—in the other. A simple classification of spending shows why that process leads to undesirable results. When you spend, you may spend your own money or someone else’s; and you may spend for the benefit of yourself or someone else. Combining these two pairs of alternatives gives four possibilities summarized in the following simple table:

Category I in the table refers to your spending your own money on yourself. You shop in a supermarket, for example. You clearly have a strong incentive both to economize and to get as much value as you can for each dollar you do spend. Category II refers to your spending your own money on someone else. You shop for Christmas or birthday presents. You have the same incentive to economize as in Category I but not the same incentive to get full value for your money, at least as judged by the tastes of the recipient. You will, of course, want to get something the recipient will like—provided that it also makes the right impression and does not take too much time and effort. (If, indeed, your main objective were to enable the recipient to get as much value as possible per dollar, you would give him cash, converting your Category II spending to Category I spending by him.) Category III refers to your spending someone else’s money on yourself—lunching on an expense account, for instance. You have no strong incentive to keep down the cost of the lunch, but you do have a strong incentive to get your money’s worth. Category IV refers to your spending someone else’s money on still another person. You are paying for someone else’s lunch out of an expense account. You have little incentive either to economize or to try to get your guest the lunch that he will value most highly. However, if you are having lunch with him, so that the lunch is a mixture of Category III and Category IV, you do have a strong incentive to satisfy your own tastes at the sacrifice of his, if necessary. All welfare programs fall into either Category III … or Category IV.

Friedman describes how these spending dynamics create a vicious cycle of bureaucratically-provided welfare:

In our opinion these characteristics of welfare spending are the main source of their defects … The bureaucrats spend someone else’s money on someone else. Hence the wastefulness and ineffectiveness of the spending. But that is not all. The lure of getting someone else’s money is strong. Many, including the bureaucrats administering the programs, will try to get it for themselves rather than have it go to someone else. They will lobby for legislation favorable to themselves, for rules from which they can benefit. The bureaucrats administering the programs will press for better pay and perquisites for themselves—an outcome that larger programs will facilitate … [T]he net gain to the recipients of the transfer will be less than the total amount transferred. If $100 of somebody else’s money is up for grabs, it pays to spend up to $100 of your own money to get it. The costs incurred to lobby legislators and regulatory authorities, for contributions to political campaigns, and for myriad other items are a pure waste—harming the taxpayer who pays and benefiting no one. They must be subtracted from the gross transfer to get the net gain—and may, of course, at times exceed the gross transfer, leaving a net loss, not gain. These consequences of subsidy seeking also help to explain the pressure for more and more spending, more and more programs. The initial measures fail to achieve the objectives of the well-meaning reformers who sponsored them. They conclude that not enough has been done and seek additional programs. They gain as allies both people who envision careers as bureaucrats administering the programs and people who believe that they can tap the money to be spent.

Friedman then contrasts the concepts of equality under law and equality of result:

“Equality,” “liberty”—what precisely do these words from the Declaration of Independence mean? Can the ideals they express be realized in practice? Are equality and liberty consistent one with the other, or are they in conflict? Neither equality before God nor equality of opportunity presented any conflict with liberty to shape one’s own life. Quite the opposite. Equality and liberty were two faces of the same basic value—that every individual should be regarded as an end in himself. A very different meaning of equality has emerged in the United States in recent decades—equality of outcome. Everyone should have the same level of living or of income, should finish the race at the same time. Equality of outcome is in clear conflict with liberty. The attempt to promote it has been a major source of bigger and bigger government, and of government-imposed restrictions on our liberty.

Friedman recounts the observations of French sociologist Alexis de Tocqueville in the 1830s:

Alexis de Tocqueville, the famous French political philosopher and sociologist, in his classic Democracy in America, written after a lengthy visit in the 1830s, saw equality, not majority rule, as the outstanding characteristic of America. “In America,” he wrote, the aristocratic element has always been feeble from its birth; and if at the present day it is not actually destroyed, it is at any rate so completely disabled, that we can scarcely assign to it any degree of influence on the course of affairs. The democratic principle, on the contrary, has gained so much strength by time, by events, and by legislation, as to have become not only predominant but all-powerful. There is no family or corporate authority … America, then, exhibits in her social state a most extraordinary phenomenon. Men are there seen on a greater equality in point of fortune and intellect, or, in other words, more equal in their strength, than in any other country of the world, or in any age of which history has preserved the remembrance. Tocqueville admired much of what he observed, but he was by no means an uncritical admirer, fearing that democracy carried too far might undermine civic virtue. As he put it, “There is … a manly and lawful passion for equality which incites men to wish all to be powerful and honored. This passion tends to elevate the humble to the rank of the great; but there exists also in the human heart a depraved taste for equality, which impels the weak to attempt to lower the powerful to their own level, and reduces men to prefer equality in slavery to inequality with freedom.” It is striking testimony to the changing meaning of words that in recent decades the Democratic party of the United States has been the chief instrument for strengthening that government power which Jefferson and many of his contemporaries viewed as the greatest threat to democracy. And it has striven to increase government power in the name of a concept of “equality” that is almost the opposite of the concept of equality Jefferson identified with liberty and Tocqueville with democracy.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll examine Friedman’s discussion of the concept of equality of opportunity and its positive incentives.