Communist China – Part 5

How China’s fertility crisis has limited its welfare state capacity.

Continuing this essay series on communist China, using Arthur Kroeber’s China’s Economy: What Everyone Needs to Know, Michael Pillsbury’s The Hundred-Year Marathon: China’s Secret Strategy to Replace America as the Global Superpower, Chris Miller’s Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology, and Elbridge Colby’s The Strategy of Denial: American Defense in an Age of Great Power Conflict, this essay will focus on how China’s fertility crisis has limited its welfare state capacity.

As Kroeber writes:

The story of China’s labor market in the reform era has been one of steady movement of workers out of agriculture and into urban employment in industry and services, and out of the state sector into the private sector … [W]hile China has created lots of jobs, maintaining full employment for its huge working-age population remains a challenge … The main story of China’s great labor migration is not movement from hinterland to coast. Rather, it is one of people moving from rural areas to urban areas—mostly nearby towns, but sometimes distant cities—to pursue higher wages … Working conditions for many Chinese are undeniably harsh. Long hours and compulsory overtime are routine in many factories; safety conditions in factories, mines, and other hazardous workplaces fall well short of Western standards; and employers have wide latitude to fire workers, dock their pay, or impose other arbitrary punishments. Workers have little recourse and no ability to organize independent labor unions. (There is a single nationwide union organized by the Communist Party, but it does little to advance worker rights and it often acts as an agent for management.) … [A]ny process of rapid change such as China has experienced inevitably creates huge social stresses. In this chapter, we will focus on two interlinked problems that, if left unaddressed, could undermine the political and economic order: inequality and corruption.

China’s growth has resulted in significant inequality of income, much greater than that in the United States. As Kroeber writes:

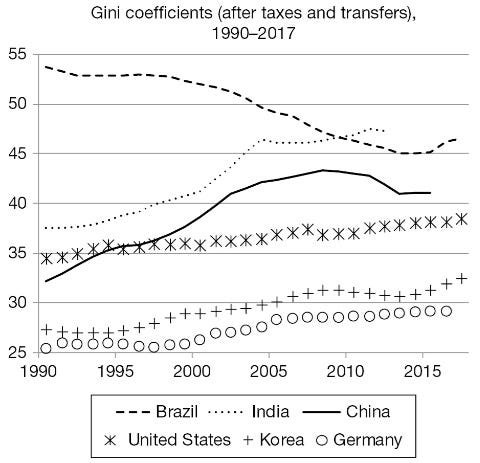

As both Chinese officials and international agencies such as the World Bank often point out, China’s economic growth since the 1980s has literally lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty. This is a great achievement. But the fruits of growth have been distributed very unevenly. By virtually any measure of income or wealth, China is now one of the more unequal societies on earth. Perhaps more important, it is the country where inequality has grown most rapidly in the past few decades. One standard measure of income inequality is the Gini coefficient (or index), developed by the Italian economist Corrado Gini in 1912 in which 0 represents perfect equality and 1 the state where all income is controlled by a single person. In practice, most countries have a Gini index of somewhere between 0.2 and 0.6. Rich countries with well-developed social welfare systems (e.g., in Scandinavia) fall at the bottom of the range; commodity-based economies where wealth is very concentrated (e.g., in Africa and Latin America) tend to be near the top. The median Gini for the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), a club of middle- and high-income democracies, is 0.31. Estimates of China’s Gini vary, but virtually all agree on two basic conclusions: China’s income inequality is very high, and it rose substantially at least until 2008. China’s income inequality is substantially greater than that of all developed countries. Figures 13.1 and 13.2, based on the most comprehensive database on global income inequality. The first figure shows the Gini coefficients for several countries, based on disposable income—that is, after all taxes have been paid and social welfare transfers have been received. (This is the standard way to report Gini numbers). It shows that China’s inequality rose sharply from 1990 to 2010, arriving at a high peak level of over 0.43. Income inequality is clearly much higher in China than in developed countries such as the United States, Germany, and South Korea.

Figure 13.1 Income inequality. Source: Standardized World Income Inequality Database, version 8.1.

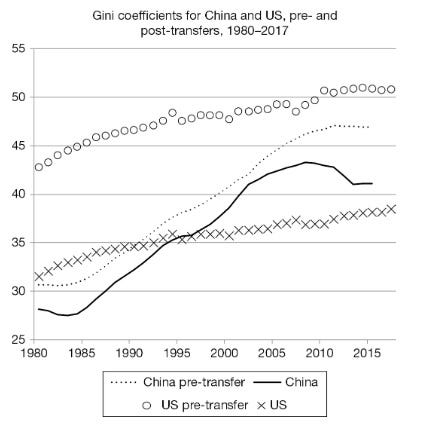

Figure 13.2 is even more interesting … [A]fter taking account of taxes and transfers, the United States is much less unequal than China. Most American politicians scurry away from the label “socialist,” but in fact the United States has a very progressive tax system and a wide range of social welfare programs that take the sting out of its very unequal income distribution.

It may be surprising to some that China has a relatively small welfare state due to the Chinese Communist Party’s plan to keep workers pacified in at least minimally productive jobs while maintaining old age social insurance for its growing older population. As Kroeber writes:

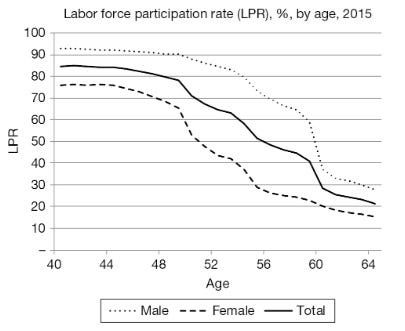

A striking fact in China is that the labor force participation rate is very high until people hit their late 40s, and then it declines precipitously (Figure 11.3). At age 48, 80 percent of urban residents are active in the workforce. By age 50, that share drops to 70 percent; and by age 60, only 29 percent. The decline in participation is particularly acute among women in their 40s and 50s.

Figure 11.3 Labor participation.

The conclusion is that China still has the ability to increase its labor force, even though the working-age population has started to decline. To do this, it must increase the participation rate, especially among older workers in the 45–65 age range, who will constitute nearly half of the working-age population by 2030. There are many ways to achieve this goal. One is to increase statutory retirement ages, which are quite low in many government agencies and SOEs (60 for men and 55 for women) … China—despite being run by an ostensibly “communist” party—has a very weak social safety net and a tax system that does little to shift income from rich to poor … [S]pending on social welfare programs is a far smaller share of China’s budget than is typical in advanced countries. One challenge for China’s leaders in the coming decades will be to build the more generous social safety net required by an older population, without falling into the trap of excessive entitlement spending that bedevils so many developed-economy governments.

Whereas free markets incentivize people to work efficiently, the Chinese model is based on simply getting people to work, regardless of their efficiency. As Kroeber writes:

A final consideration is that the economic impact of labor is partly a function of the number of workers, but more importantly of the productivity of those workers. The importance of labor productivity is illustrated by the fact that China’s economy is still only about three-quarters the size of the U.S. economy, even though China’s labor force is nearly five times bigger. This implies that, on average, a Chinese worker produces only about one-sixth of what her U.S. counterpart does. So to offset the economic impact of a shrinking working-age population, the government should focus not just on increasing participation but also on boosting productivity.

To better understand China’s odd strategy, as Pillsbury writes, it’s crucial to see that China operates on a mercantilist strategy that was replaced by free markets in most of the world long ago:

An important element of China’s grand strategy is derived from what is known in the West as mercantilist trade behavior—a system of high tariffs, gaining direct control of natural resources, and protection of domestic manufacturing, all designed to build up a nation’s monetary reserves. The Chinese invented mercantilism (zhong-shang), and the country’s leaders reject the West’s contention that mercantilism has been rendered obsolete by the success of free markets and free trade. Because it embraces mercantilism, China is wary that trade and markets will always provide sufficient access to needed resources. China’s leaders have an almost paranoid fear of a coming crisis leading to regional or global resource scarcity. As a result, they are determined to obtain ownership or direct control of valuable natural resources overseas—just as Europe’s mercantilist monarchs attempted to do by colonizing the New World in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

This strategy, besides leading to the surprising result that China’s has massive income inequality and a small welfare state, also leads to the surprising result that China has fewer resources to devote to its military. As Pillsbury writes:

Consider also the contrast between American and Chinese views about the optimum size of military forces. Many of America’s greatest military triumphs were achieved through large armies. Grant overwhelmed Lee with more men and more guns. On June 6, 1944, Dwight Eisenhower sent the largest armada in history to Normandy. Even in recent times, the so-called Powell Doctrine has advocated the necessity of a force far larger than the enemy’s. In contrast, the Warring States period did not involve great military outlays. Nonviolent competition for several decades constituted the main form of struggle. A famous strategy was to deplete an adversary’s financial resources by tricking it into spending too much on its military. Two thousand years later, when the Soviet Union collapsed, the Chinese interpretation was that the Americans had intentionally bankrupted Moscow by tricking it into spending excessively on defense. As of 2011, while the United States spent nearly 5 percent of its GDP on its military, the Chinese spent only 2.5 percent of theirs.

The metrics that most concern Chinese officials are economic, not military. As Pillsbury explains:

Chinese military and intelligence services use quantitative measurements to determine how China compares with its geopolitical competitors, and how long it will be before China can overtake them. When I read these quantitative measurements in a difficult-to-obtain book written by Chinese military analysts, I was surprised to see how precisely China measures global strength and national progress. The most startling revelation was that military strength comprised less than 10 percent of the ranking. After the collapse of the Soviet Union—which had the world’s second-mightiest military—the Chinese changed their assessment system to put more emphasis on the importance of economics, foreign investment, technological innovation, and the ownership of natural resources.

China’s mercantilist strategy, in which it prioritizes its economic strength in the world, also dictates that it will prioritize energy use over environmental considerations. As Kroeber writes:

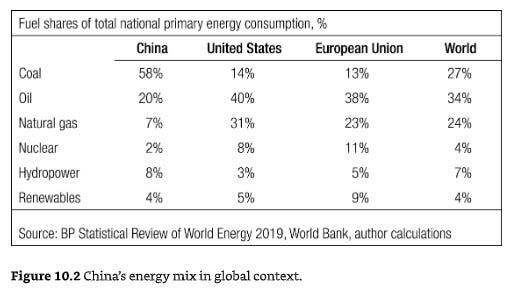

China is the world’s biggest user of energy, accounting for a quarter of global consumption. China burns 40 percent more energy than the United States and nearly twice as much as the European Union. It is by far the world’s biggest user of coal, accounting for about half of global consumption. Consequently, China is also the world’s biggest contributor to carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions that are the main driver of global warming … China’s numbers are dismal. It needs to burn the equivalent of 1,763 barrels of oil to generate a million dollars’ worth of economic output, more than twice the figure of the United States and three times that of the European Union. China is by a sizable margin the world’s most energy-intensive major economy. China’s economy relies far more on manufacturing, and industry generally than that of any other major country. The industrial sector uses a lot more energy for each dollar of output than the service or agriculture sectors, so an economy that relies mainly on industry will consume more energy than an economy of equal size that is based mainly on services. [China’s] reliance on coal … accounts for nearly two-thirds of its electric power generation. (By contrast, coal fuels less than a quarter of power production in Europe and 30 percent in the United States.) This leads to relatively high energy intensity because coal is a less efficient fuel for power production than the main alternative, natural gas: it takes about 25 percent more coal than gas to produce a unit of electricity. Economically, China’s heavy reliance on coal makes sense because it has abundant domestic supplies, whereas natural gas must largely be imported at a high cost. Coal accounts for 58 percent of total primary energy demand, more than double the world average of 27 percent (Figure 10.2) …

[I]n the past decade … annual output of both nuclear power and hydropower has more than doubled, and electricity from renewable sources has risen almost twentyfold. This has dented coal’s dominance: its shares of primary energy consumption and electricity output has fallen by 12 and 15 percentage points, respectively, since 2005. But given the huge installed base of coal power plants, some projections suggest that coal may still account for around half of China’s energy mix as late as 2050 … Despite its enormous energy use, China has traditionally satisfied most of its demand from domestic sources … In theory, China could greatly increase its gas production [and reduce its greenhouse gas emissions], as the United States has, by unlocking its reserves of shale gas, which by some estimates are bigger than those of the United States. But doing so will be very difficult because the geology of China’s shale formations is markedly different from that of the United States, and new and expensive extraction technologies may be required … By 2014, the last year for which fully comparable international data are available, China accounted for 30 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, more than the United States and European Union combined.China’s environmental damage has attracted worldwide notice and with good reason. Rapid industrialization has exacted a toll in extreme degradation of the country’s air, water, and soil. In January 2013, Chinese and global news media focused the world’s attention on an especially terrible smog episode in Beijing—the so-called Airpocalypse—when the skies darkened under a load of particulates measured at nearly 800 micrograms per cubic meter, more than thirty times the maximum level considered safe by the World Health Organization. This dreadful event became a catalyst for more serious governmental action to combat pollution. China’s environmental challenges need to be put in international and historical perspective. Every country that has grown rich has gotten quite dirty along the way … China is likely to remain an environmental underperformer for many years to come … Media exposure of pollution problems is to some extent tolerated: in this area as in others, the central government is happy for the press to unearth problems that local officials would rather keep buried. But once the authorities in Beijing think they know enough, they tend to clamp down on reporting. A classic example of this pattern came in March 2015, when veteran CCTV investigative reporter Chai Jing distributed a scathing documentary about air pollution, Under the Dome, over the Internet. Within days, the video was watched by over a hundred million people. Then the censors stepped in, forced the video to be removed from all websites, and closed off social media discussions. In a freer country, this documentary could have prompted a large-scale, long-running national debate on how to balance the imperatives of environmental protection and economic growth. In China, this conversation was strangled in the cradle.

As Pillsbury writes of the pollution problem in China:

Pollution even crosses the Pacific Ocean and accounts for 29 percent of particulate pollution in California.50 And, of course, global warming respects no national boundaries … As China continues to grow, the pollution problem will only worsen. To slow its emissions rates, China would have to seriously compromise its growth rates, which are sacrosanct to all other policy objectives … To stay in power, China’s leadership knows it needs rapid growth. If we project the current impasse forward three decades, the effects are alarming. Since the 1980s, China has built ten thousand petrochemical plants along the Yangtze River and four thousand plants along the Yellow River. As a result of these factories and China’s choice to prioritize development over environmental considerations, 40 percent of the country’s rivers are seriously polluted, and in 20 percent of its rivers the water quality is too toxic to touch safely, let alone drink. At least 55 percent of the groundwater in China—and there is not that much groundwater in China—is unfit for drinking. China’s neighbors are already feeling the spillover effects of its reckless approach to development. Due to water contamination in China, much of the country’s fishing industry has moved into the contested waters of the East China Sea, the South China Sea, and the Pacific Ocean. In 2011 alone, the South Korean Coast Guard sent back 470 Chinese fishing boats for illegally entering South Korean waters. There are regular disputes like these between China and Vietnam, the Philippines, and Japan.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll examine China’s massive economic growth, and its impact on China’s ability to leverage its economic strength to further its global ambitions.

Paul, One hears about the fertility crisis overtaking the Western world. But hadn't really thought through the one child impacts in China. You always teach me something. Thanks for this labor of love.