Communist China – Part 4

Unique aspects of China’s population and geography.

Continuing this essay series on communist China, using Arthur Kroeber’s China’s Economy: What Everyone Needs to Know, Michael Pillsbury’s The Hundred-Year Marathon: China’s Secret Strategy to Replace America as the Global Superpower, Chris Miller’s Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology, and Elbridge Colby’s The Strategy of Denial: American Defense in an Age of Great Power Conflict, this essay will focus on unique aspects of China’s population and geography.

As Kroeber writes:

It is an obvious fact, but it bears repeating: China is the world’s largest nation by population (1.4 billion) and its fourth largest by area, with a geographic size almost identical to that of the United States. Its size presents China with an unusual set of constraints and possibilities … [A] common feature of China’s economy in both the Maoist and reform eras: the main goal throughout has been to mobilize resources. Maximizing the efficiency with which those resources are used has always been a secondary concern. This often distresses economists from rich countries, where virtually all economic growth and improvement in living standards come from improvements in efficiency. Visitors to China observe the waste and inefficiency visible everywhere and often conclude that the economy will soon hit a crisis. These predictions have always been wrong, not because observers are wrong about the degree of waste, but because they fail to realize that in a country of China’s size, such waste can be irrelevant as long as it is a by-product of an effective process of meeting basic needs [including the basic of people’s employment and housing]. To cite a simple example: in each year of the decade 2000–2010, just to meet the basic employment and shelter needs of its population, China had to create over 20 million new jobs (nearly equivalent to the entire population of Australia), and build 8 million new urban housing units—six times as many as the average in the United States during that period and four times the peak rate during the U.S. housing bubble. It is hardly surprising that during this scramble many fairly useless jobs were created and many housing units were built that had to wait months or years for buyers. This is not to argue that China’s growth had to be wasteful and inefficient, or that this level of waste can go on forever. Other, more efficient (and probably slower) growth paths were certainly viable. The point is simply that China’s enormous size gave its leaders the option of a high-speed growth model that emphasized quantity over quality.

Regarding China’s geography, Kroeber writes:

How does China’s geography affect its economy? Three features of China’s geography have a particular impact on its patterns of economic development: The “Hu Line,” running diagonally from the far northeast to the far southwest, bisecting China into a well-watered, densely populated half and an arid, sparsely populated one. The division between the long coastline where most export-oriented activity clusters and the vast landlocked hinterland. The two main rivers, the Yellow and the Yangtze, which influence crop patterns and provide channels for inland development. The half east and south of the line contains 94 percent of China’s population and most of the country’s available water, with annual precipitation ranging from 500 to 2,000 millimeters. The half west and north of the line contains just 6 percent of the population (many of them ethnic minorities such as Mongolians, Tibetans, and Uighurs) and is very dry, with most regions receiving no more than 400 millimeters of precipitation a year.2 This area does, however, contain large deposits of oil, gas, and minerals, so it is an important part of China’s natural resource endowment.

Communist China had the good fortune to be close to more economically vibrant nations. As Kroeber writes:

Geography and historical circumstance have great impact on a country’s ability to grow. China had at least three pieces of good luck in this respect. First, it was in a neighborhood—East Asia—which by the late 1970s was already very dynamic. Proximity to rich neighbors is a key determinant of economic growth, and in this regard China won the lottery. Many nearby countries with successful companies were eager to invest in China to take advantage of its lower costs and gain access to its potentially huge market. Second, China chose to open up just at the moment when logistics technologies such as containerized shipping made it cost-effective for companies to split up production chains so that high-cost components produced in one country could be shipped to a second (low labor-cost) country for final assembly and then shipped to consumers in a third and often very distant country. In other words, China opened up right when economic globalization was beginning to go into high gear, and it was perfectly placed to become the final assembly hub for Asian production chains.

As Kroeger explains, China has strategically used the free markets of its neighbors to bolster its own central control of its own population:

In December 1978, however, at a key meeting of the CCP’s central committee, Deng Xiaoping emerged as China’s top leader … Deng launched a strategy known as “reform and opening” (in Chinese, gaige kaifang). The general aim was that China would reform its domestic economy by gradually reducing the role of the state and increasing the role of markets; and it would open to the outside world, welcoming ideas from other countries and inviting companies to invest in China and export China-made products to the world … In 1962, development economist Alexander Gerschenkron introduced the concept of “the advantage of backwardness.” His idea was that a poor country could grow very fast for a long time simply by marrying the technology already developed in rich countries with its low- cost labor force. This kind of growth— which does not require much innovation— is called “catch-up” growth. Like the other East Asian success stories, China’s involved a lot of this catch- up growth thanks to its large supply of rural workers who were willing to work in modern factories for relatively low wages. But China in 1979 also had another “advantage of backwardness”: its economy was organized around the socialist principles of government ownership of assets and control of prices. Simply by gradually letting go of these state controls, China enjoyed a productivity boom as economic decision making shifted from crusty state bureaucrats to private and public actors who, driven by increasing market forces, tried to squeeze more productivity and profit out of the assets they controlled … China, unlike most authoritarian states, benefits from the economic dynamism and entrepreneurship enabled by local experimentation. On the other hand, formal centralization means that when Beijing decides on a major national infrastructure project—such as an interstate highway system or high-speed rail network—it has the ability to mobilize resources on a large scale to achieve its aims.

This strategy contrasts with that of the former communist Soviet Union. As Kroeber writes:

The first key to understanding why China has not lapsed into economic stagnation or evolved into a democracy is to examine the lessons its leaders learned from the failure of other communist states, notably from the traumatic collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. In the early 1990s, China’s political position seemed very shaky. Protests in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in the spring of 1989 swelled at their height to over a million demonstrators, who denounced official corruption, runaway inflation, and the lack of political freedoms. The Communist Party under Deng Xiaoping restored order at the cost of a bloody crackdown and the house arrest of Zhao Ziyang, who until late May that year had been the party’s top official and had spearheaded many of the economic reforms of the 1980s. In the next 2 years, China suffered economic sanctions by the United States and other Western countries, and its economic growth rate sagged to an average rate of 4 percent in 1989–1990—a recession compared to the 10 percent average growth rate in the prior decade. Conservative officials, led by Deng’s rival Chen Yun and Premier Li Peng, blamed the political unrest on Deng’s reformist economic policies. The country was diplomatically isolated and in economic and political lockdown. Meanwhile, the rest of the communist bloc was crumbling with a speed unimaginable just a few years earlier. Communist regimes in the USSR’s satellite states in Eastern Europe all disintegrated by early 1990, and by Christmas 1991 the Soviet Union itself had fallen apart: the Communist Party lost power after a failed coup against Mikhail Gorbachev, fourteen republics from Lithuania to Kazakhstan declared independence, and Boris Yeltsin installed himself as the noncommunist president of a reduced Russian Federation. In such circumstances, it was easy to imagine either that China would be the next domino to fall or that the party would tighten its grip on power by crushing dissent and reining in the economic reforms that had proved so politically disruptive. In fact, it did neither. By 1991, the economy was picking up steam again, and in early 1992, Deng launched a master stroke with his celebrated “Southern Tour.” Accompanied by senior military leaders, he visited the hot spots of economic reform in south China, beginning with the special economic zone of Shenzhen, right next to Hong Kong, which had been the laboratory for his boldest experiments. [But] [a]n old revolutionary, Deng was as committed as anyone to preservation of the party’s monopoly on power. But he gambled that the best way to preserve that monopoly was to run a dynamic economy that boosted living standards at home and raised China’s international prestige and leverage. [In China] [e]conomic reform must come first, and political reform— if ever— a distant second. Or in his own words, plastered prominently on billboards throughout China in the 1990s: “Development is the only iron law.” In this respect, he differed diametrically, and self-consciously, from Gorbachev, who began with political reforms in the hope that they would help unblock bureaucratic resistance to economic reforms. Deng, long before Tiananmen, declared Gorbachev to be “an idiot” for putting political reforms ahead of economic ones. Deng’s judgment about the importance of strong economic growth was later validated by a series of studies of the collapse of the USSR conducted by party scholars in the 1990s. These scholars concluded that the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) fell for four main reasons: The economy did not grow fast enough, leading to frustration and resentment, and this failure resulted from insufficient use of market mechanisms. The CPSU’s propaganda and information systems were too closed and ideologically rigid, preventing officials from getting accurate and timely knowledge about conditions both inside and outside the Soviet Union. Decision making was far too centralized and hence far too slow. Once reforms started under Gorbachev, they undermined the core principle of the party’s absolute monopoly on political power. These findings have continued to inform Chinese policymaking over the past two decades … With strengthened legitimacy, the party’s grip on power becomes more secure, and most people find the risk of switching to another, untried system to be unacceptably high.

What China has done, and which the former Soviet Union didn’t do, was strategically use free markets where they existed to assuage its population while still maintaining strict party control over most significant businesses. As Kroeber writes:

China began its high-growth era in 1979 with virtually all assets in state hands; 40 years later, China still has by a wide margin the biggest state sector of any major economy. As noted earlier, China’s political system hinges on the Communist Party having an outsized influence on all organized activity, and corporations are no exception … One of the groundbreaking economic reforms of the early 1980s, the establishment of special economic zones (SEZs), was specifically designed to lure foreign companies to set up export manufacturing factories. One of the enduring impacts of this is that, even today, over 40 percent of all Chinese exports are produced by foreign firms. This state of affairs is utterly different from that of the other East Asian countries, whose exports are virtually all recorded by domestic firms. What accounts for this extraordinary surrender of economic sovereignty, which has led many Chinese critics to complain that China was simply renting out its vast army of cheap workers to foreign capitalists, who grew rich on the proceeds? One reason is that, in the aftermath of the Mao era and the chaos of the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), China found itself in a position of extreme technological backwardness. It therefore required a strategy for rapid import of foreign technology. Another explanation for China’s FDI [foreign direct investment] reliance is political. Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan were part of the United States’ alliance structure in East Asia. They therefore benefited from technical assistance, educational exchanges, and essentially unfettered access to America’s gigantic market China, on the other hand, lay outside the U.S. alliance structure, although there was an alignment of convenience with the United States from the late 1970s until 1989, driven by a shared strategic desire to contain the Soviet Union. China would never enjoy the kind of privileges that its East Asian neighbors extracted from the United States.

This strategy was necessary to pacify China’s large population, which grew rapidly, until a more recent fertility crisis there. As Kroeber explains:

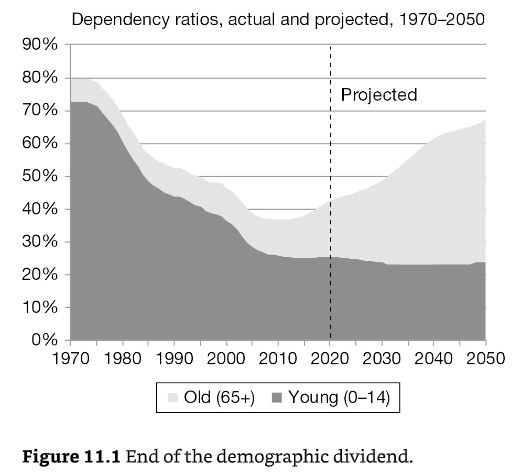

By the early 1970s, government officials became worried that the population was expanding too rapidly and that it would become difficult for the nation to feed itself or provide enough jobs. In 1973, it introduced the “later, longer, fewer” campaign, which encouraged couples to marry later, space children more widely, and limit their offspring to two in cities and three in the countryside.2 In the 1970s, the fertility rate plunged from 5.8 to 2.4, partly due to these policies and partly thanks to the normal impact of lower childhood mortality. Despite this impressive drop, which brought China’s fertility close to the “replacement rate” of 2.1, which enables a stable population size, the government in 1980 introduced the draconian “one-child” policy, which contributed to a further fall in the birth rate in the 1980s and 1990s. The combination of excessive deaths during the famine years (which reduced the number of people entering retirement in the 1980s), the big baby boom of the 1960s, and the large fertility drop that began in the 1970s produced a deep, long-lasting demographic dividend (Figure 11.1). Between 1975 and 2010, the dependency ratio—the number of young (under 15) and old (over 65) people for every 100 working-age people—fell from 80 to 36. During the same period, the national savings rate rose from 33 percent of GDP to over 50 percent, real annual growth in investment spending averaged 12 percent, and the economy grew at an average rate of about 10 percent a year. The relationship between demographics and economic growth is far from straightforward, and it would be wrong to say that this big demographic dividend caused China’s fast economic growth. But it was clearly an important favorable condition. The demographic dividend helped create the opportunity for fast economic growth, and the reforms that began in 1978 enabled that opportunity to be realized.

But then China implemented a disastrous population control policy. As Kroeber writes:

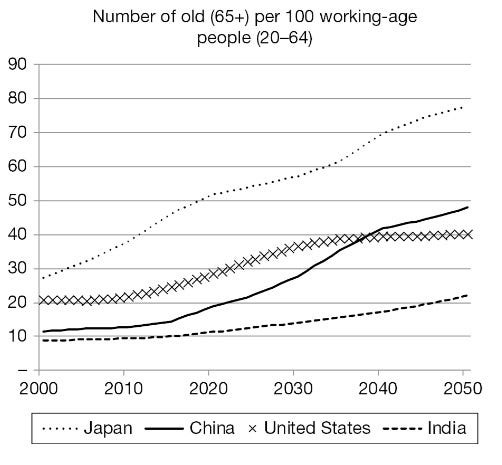

Unfortunately, China is now coming out on the other side of the demographic dividend, and in the coming years the dependency ratio will rise. The fall in dependency occurred entirely because the young people of the 1960s–1970s baby boom became workers. The rise in dependency over the next few decades will occur entirely because those baby-boom workers are turning into retirees. In 2020, a bit less than one in five Chinese is over the age of 60; that figure will rise to one in four by 2030, and one in three by 2050. The burden on the pension, health care, and social services systems will grow enormously. In 2020, there are about five people of working age (20–64) for every person of retirement age (65 or older). By 2035, there will be just over three workers per retiree, about the same as in the United States today. And by 2050 there will be only two—about the same figure as in present-day Japan, a famously “old” society. In the space of less than three decades China will move from being a relatively young society to a very old one (Figure 11.2). China’s future demographic trajectory is certainly one of rapid aging, and this will put downward pressure on economic growth and push up the fiscal burden of the social security system.

Figure 11.2 The aging population. Source: United Nations World Population Prospects.

During the 1980s, enforcement of the new [one-child] policy was chaotic and fluctuating: sometimes savage, with widespread reports of forced abortions and forced sterilizations; and sometimes relaxed, leading to surges of births in the countryside. By the late 1980s, the policy was codified in a more pragmatic way, with a blanket exception for rural families (who were permitted to have a second child if their first was a girl) and more relaxed quotas for ethnic minorities. It might more accurately be called the “one-and-a-half-child policy,” since under perfect enforcement, only 60 percent of families would be limited to one child, and the fertility rate would be about 1.5. This policy remained in full effect for a quarter-century, until a slight easing in late 2013. In late 2015, policy was changed to allow all couples to have two children. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that the one-child policy was one of the worst major policies of the reform era. It was unnecessary when it was introduced; savage at times, and consistently intrusive and demeaning to the women who had to endure annual birth-control examinations even if they were not forced into abortions or sterilization; and far more long-lasting than it should have been. The main reason it endured is bureaucratic inertia: the State Family Planning Commission (SFPC) that enforced it had 500,000 employees and six million part-time workers, and it collected millions of dollars in fines every year. It had every incentive to keep the policy in place simply to protect all these jobs and revenues, and it did so by constantly overstating the fertility rate and claiming that its services were still urgently needed. Only after the 2010 census conclusively proved that the fertility rate was far lower than the SFPC had claimed, and after the SFPC was deprived of its separate status and put under the Ministry of Health, could the policy finally start relaxing … [E]vidence so far is that urban China is not immune to the low-birthrate dynamics now common in most other East Asian countries, which are driven by the high cost of raising children, cramped living spaces, and limited availability of affordable childcare.

As Nicholas Eberstadt writes on Chinese demographic trends:

China is in the midst of a quiet but stunning nationwide collapse of birthrates. This is the deeper, still largely overlooked significance of the country’s 2022 population decline, announced by Chinese authorities last month. As recently as 2019, demographers at the U.S. Census Bureau and the United Nations were not expecting China’s population to start dropping until the early 2030s. But they did not anticipate today’s wholesale plunge in childbearing. Considerable attention has been devoted to likely consequences of China’s coming depopulation: economic, political, strategic. But the causes of last year’s population drop deserve much closer examination. China’s nosedive in childbearing is a silent alarm. It signals deep disaffection with the bleak future the regime is engineering for its subjects. In this land without democracy, the birth collapse can be read as a landslide vote of no confidence in President Xi Jinping’s rule … According to the data, births in China have fallen steeply and steadily since 2016, year after year. In 2022, China had only about half as many births as just six years earlier (9.6 million vs. 17.9 million). That sea change in childbearing predated the coronavirus pandemic, and it appears to be part of broader shock, for marriage in China is also in free fall. Since 2013 — the year Xi completed his ascent to power — the rate of first marriages in China has fallen by well over half. Headlong flights from both childbearing and marriage are taking place in China today. Of course, fertility levels and marriage rates are dropping all around the world. But these declines tend to be gradual, occurring across decades. China has been hit by seismic demographic jolts. Birth shocks of this order almost never occur under stable modern governments during peacetime. Swift and sharp fertility crashes instead usually reflect catastrophe: famine, war or other shattering upheavals … Yet China — amid social order and economic health, not apocalyptic upheaval — has just experienced its own harrowing birth plunge. Why? The answer most likely lies in the dispirited outlook of the Chinese populace itself. Absent disaster, one of the most powerful predictor of fertility levels the world over — across countries, ethnicities and time — turns out to be the number of children that women (also men) happen to want. More than any other factor, human agency matters in national birth patterns, a truth that should come as no surprise … If the 2022 birth tally is accurate, nationwide fertility would now be less than half the replacement rate. Even if the collapse is arrested and fertility remains at that level, each new generation in China will be less than half as large as the one before it … The timing of China’s birth collapse matters: The downward spiral commenced immediately after the Chinese Communist Party suspended decades of coercive birth-control policy … Beijing has not yet figured out how to command the people to feel optimism about their personal futures — or thrill at the prospect of bringing more babies into a dystopian world of ubiquitous facial recognition technology, draconian censorship and the new high-tech panopticon known as the “social credit system.” Instead, we see millions of young people joining spontaneous movements expressing alienation from work — tang ping (lying flat) — and from Chinese society itself — bai lan (let it rot). The Xi regime doesn’t know what to do about this new form of internalized civil disobedience. Last year, during one of the regime’s innumerable, drastic pandemic lockdowns, a video went viral in China before authorities could memory hole it. In the video, faceless hazmat-clad health police try to bully a young man out of his apartment and off to a quarantine camp, even though he has tested negative for the coronavirus. He refuses to leave. “Don’t you understand,” they warn, “if you don’t comply, bad things can happen to your family for three generations?” “Sorry,” he replies mildly. “We are the last generation. Thank you.”

In the next essay in this series, we’ll explore how China’s fertility crisis has dramatically limited its welfare state capacity.